6 minute read

Up Stream

Up Stream

How lessons from the past are directing our company’s future.

Advertisement

By; Kevin Rogers

I was born in 1977, right between two of the worst oil crises in US History. In November 1973, The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) agreed to an embargo that helped to tip the already struggling US economy into a recession. The following 24 months saw unemployment rates climb from 4.8% to 9.0% and the major markets lost nearly half their value. Perhaps one of the most interesting facts about this period in US history is that most Americans under 40 know very little about it, much less understand it. And they may not realize that the same principle of imbalance that disrupted the US economy in 1973 could be happening again - only this time it won’t be gasoline, it will be your clothing.

Let’s say for a minute that you really like carrots. If you eat 10 carrots a day, but your garden can only yield 4, then the other 6 must come from somewhere else. By that math, your carrot trade imbalance would be 60%. This only becomes a problem if you can’t find someone to sell you six more carrots at an economical price. If you can’t, you’re generally left with a few choices; pay a lot more for your carrots, learn to go without, figure out how to grow your own, or worse – go to war over carrots. Fortunately for you, learning to grow carrots isn’t that difficult, but what if it wasn’t carrots, what if it was something far more complicated, like the proprietary stretch-woven welded seam jacket you’re wearing while harvesting your carrots?

To be fair, the ’73 recession wasn’t entirely caused by a petroleum trade deficit, but it exposed the inherent liabilities that come with heavily out-sourcing core commodities. US dependence on foreign oil had been steadily growing since the mid 1950’s, but during 1973 alone, OPEC increased the price per barrel north of 400%. Not only were we hooked on foreign oil, we also knew there wasn’t an easy way out. The feeling of helplessness was very un-American, and energy independence became an enduring theme throughout the next several decades. New legislation was drafted to lower the nation’s speed limits to 55 and campaign promises were issued from the next seven US presidents, from both sides of the isle, all promising to ween ourselves through domestic oil production and alternative energy.

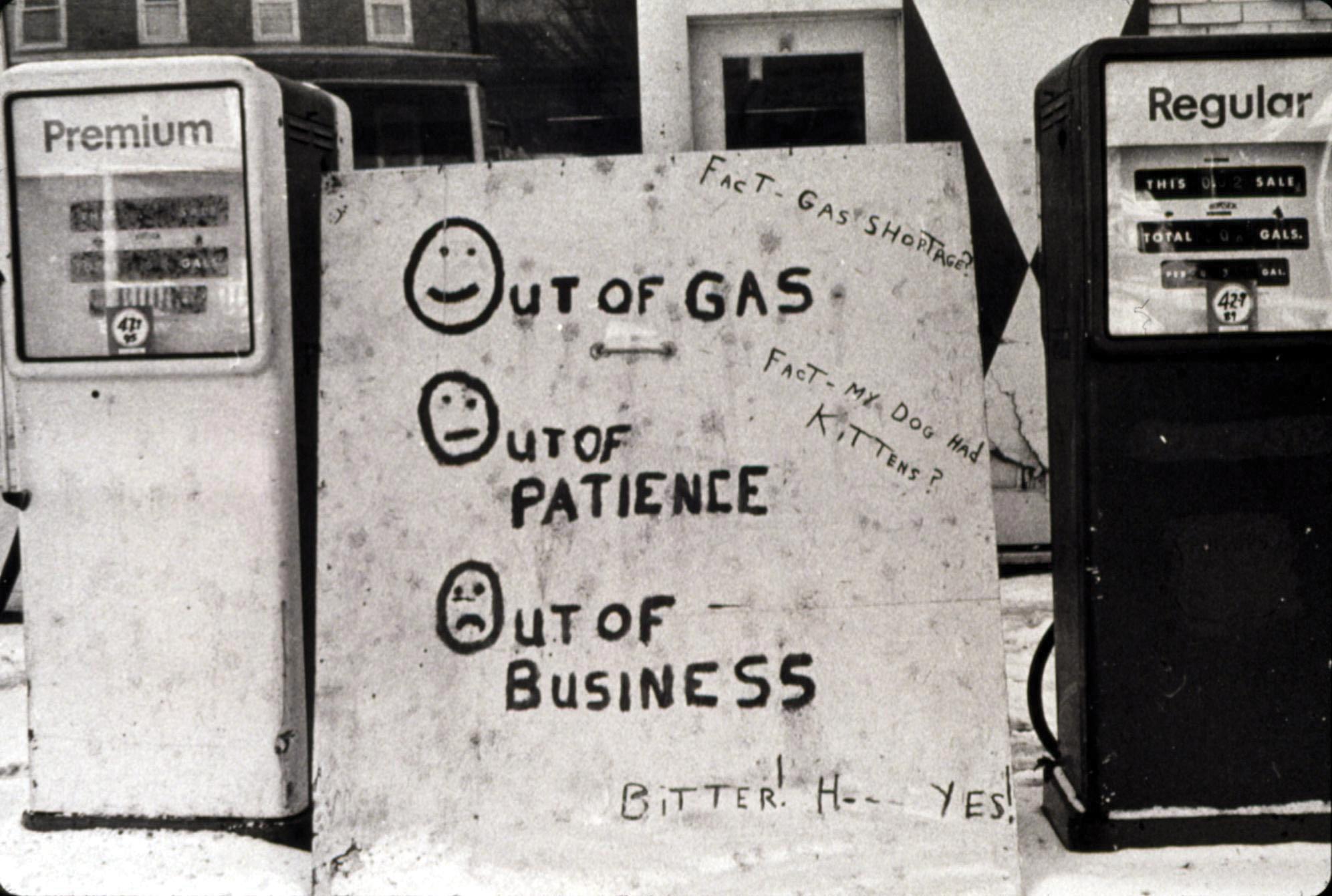

1973 gasoline shortage

Everett Historical Collection

So how is clothing like oil? Unfortunately, it’s more similar than most people realize.

First, they’re both necessary commodities, required to sustain a population. Second, we consume far more than we produce (yes, we are still a net importer of petroleum). Third, they cost the average American about the same amount of money. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), Americans spent an average of $1,400 in 2015 just to put gas in their tank. In 2016, the Bureau of Labor Statistics' Consumer Expenditure Survey reported that Americans spent an average of $1,800 annually on clothing and related services. In other words, each American is spending roughly the same on clothing as they are on gasoline - Big deal right?

Maybe.

US dependency on foreign oil peaked at 60% in 2005, so how does our dependency on foreign apparel measure up? According to the American Apparel & Footwear Association more than 97% of apparel and 98% percent of all shoes sold in the U.S. are made overseas. Those figures represent a significant paradigm shift when contrasted against the 1960s, when roughly 95 percent of apparel worn in the U.S. was made domestically.

Can’t we just bring it back? It’s not that simple. Remember, these aren’t carrots.

says Edward Hertzman, a consultant and founder of Sourcing Journal, a trade publication covering the apparel and textiles supply chain. “The price of labor, without a doubt, just knocks everything out. If a worker in the US makes $15 or $16 an hour, in one day they will earn more than someone in Bangladesh earns in a month.”

While the cost of labor has become the scapegoat for why the jobs left the US in the first place, it’s not nearly as responsible for why they’re not making their way back. “We don’t have trained people that could do that job,” Hertzman continues. “We’re no longer a country built on manufacturing. Whatever manufacturing we do have, it’s not based around the garment industry.”

He’s right, but perhaps on a scale most Americans are not familiar with. Below is a graph illustrating the job losses suffered by each of the primary US manufacturing market segments. Textiles and apparel round out the bottom three.

Over the last 3 decades manufacturing jobs have taken on a third-world stigma, especially those in the apparel industry, primarily thought to serve citizens of less developed nations. Most Americans are mistakenly lulled into a sense that the work they are doing is simple and repetitive. But the apparel manufacturing process has evolved into a sophisticated, technological operation that requires highly skilled labor and decades of experience, just keep up with the standards of today.

BJ Minson, Engineer and Founder of GRIP6 said “Buying the machine is the easy part. Finding someone in the US that has the experience to run it is the real challenge. The reason we make our products in the US is simple. Manufacturing is one of the key drivers of the economy. It generates more money, innovation and technology than any other sector. Why would we ever want to give that up? It feels like a big mistake to let that go away. There are so many things that we no longer know how to make and to be honest, it makes me sad. I know we're not single-handedly changing the world with our commitment to domestic manufacturing, but at least we're trying to be part of the solution."

There are a lot of companies that would disagree with BJ on this issue. In fact, if manufacturing trends are any indication, 97% of companies disagree. Steven Rattner, who served as a counselor to the Secretary of the Treasury under the Obama administration said, “Basic economics tells us that if another country can make something more cheaply than we can, we should focus our efforts on products we make less expensively and then trade them for the other goods or services. That’s happened in spades in the post-World War II period. The result, for virtually all Americans, has meant lower prices.”

Rattner’s views are shared by most, but BJ has a slightly different take. “It isn’t always about saving money”, he says. "There is something deeply satisfying about building your own physical products. It comes with a level of ownership and pride that you won't get when you outsource. Manufacturing in-house is hard, but it enables us to continually improve our quality, reduce our costs and design new products quickly. You forfeit a lot of those benefits when you rely on outside suppliers.”

“Most US apparel companies are really just marketing agencies. They don't actually make anything tangible, they make ads. In the extreme, too much dependency is a recipe for risk, and as far as the US apparel industry is concerned, we are in the extreme."

This extreme imbalance has garnered attention from more than just start-up companies. In 2016, Walmart, the largest brick and mortar retailer on earth, committed 250 billion dollars through 2023 to support manufacturing jobs in US. The first sentence of their press release announcing the initiative read, “Providing affordable goods isn’t the only way we aim to make an impact. We’re also heavily invested in the communities we serve.” The program provides funding for innovation in manufacturing technology . It also includes 10 million in grants for specific US manufacturing segments - the first one on the list, was textiles. If “bringing back apparel manufacturing is an impossible task” Why is the worlds biggest retailer trying to do just that?

BJ Minson, Founder of GRIP6 digs in to fix an ailing tumbler

Kevin Rogers

Perhaps we’re beginning to acknowledge the side effects of trading our wealth of manufacturing knowledge for material wealth? Can the prospect of cheap clothing be held above the human intellectual capital we are sacrificing to acquire it? Or can we re-evaluate our dependency on foreign apparel in an effort to establish a free trade balance that promotes an increased US textile manufacturing presence while maintaining support for our overseas trading partners?

Our mission at GRIP6 is to swim against the current. We realize our impact is small, but in some measure, we want to do our part to help pave the way for future businesses who are repeatedly being told that it isn’t possible to manufacture apparel in the US. It is possible, we do it every day, and we don’t do it because it’s cheap, we do it to learn, get better, and evolve. Whenever you purchase a GRIP6 product, you’re also buying the idea that building tangible goods, right here in our own backyard, is still a viable proposition this country.