4 minute read

ALLERGIC RHINITIS IN FOCUS

One of the most common autoimmune conditions, allergic rhinitis can significantly impact quality-of-life, but a range of effective treatments are available cent of individuals diagnosed with the condition develop symptoms before the age of 20 years. Older children have a higher prevalence than younger children with a peak occurring at ages 13-to-14 years. During early childhood, boys are more likely to be affected by AR than girls, during puberty girls have a higher incidence, and by age 20 and over the prevalence rates among men and women are equal.

Allergic rhinitis (AR) is an inflammatory disorder of the nasal mucosa induced by immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated reactions to inhaled allergens. It is one of the most common chronic conditions globally causing a major health burden and is associated with substantial economic costs. AR often co-occurs with asthma and conjunctivitis and is also associated with atopic dermatitis and nasal polyps. It is estimated that up to 50 per cent of people with asthma and up to 30 per cent of people with eczema also have AR. Classic symptoms of the disorder are nasal congestion, nasal itch, rhinorrhoea and sneezing. A less recognised symptom is post-nasal drip. AR is frequently associated with allergic conjunctivitis with redness, tearing, and itching of the eyes. Approximately 60 per cent of patients with AR have concomitant allergic rhino conjunctivitis. AR symptoms can be debilitating, resulting in sleep disturbance, fatigue, depressed mood and decreased function that impairs quality-of-life and productivity.

AR has long been considered a disorder of the nose and nasal passages, however, evidence suggests that it may represent a

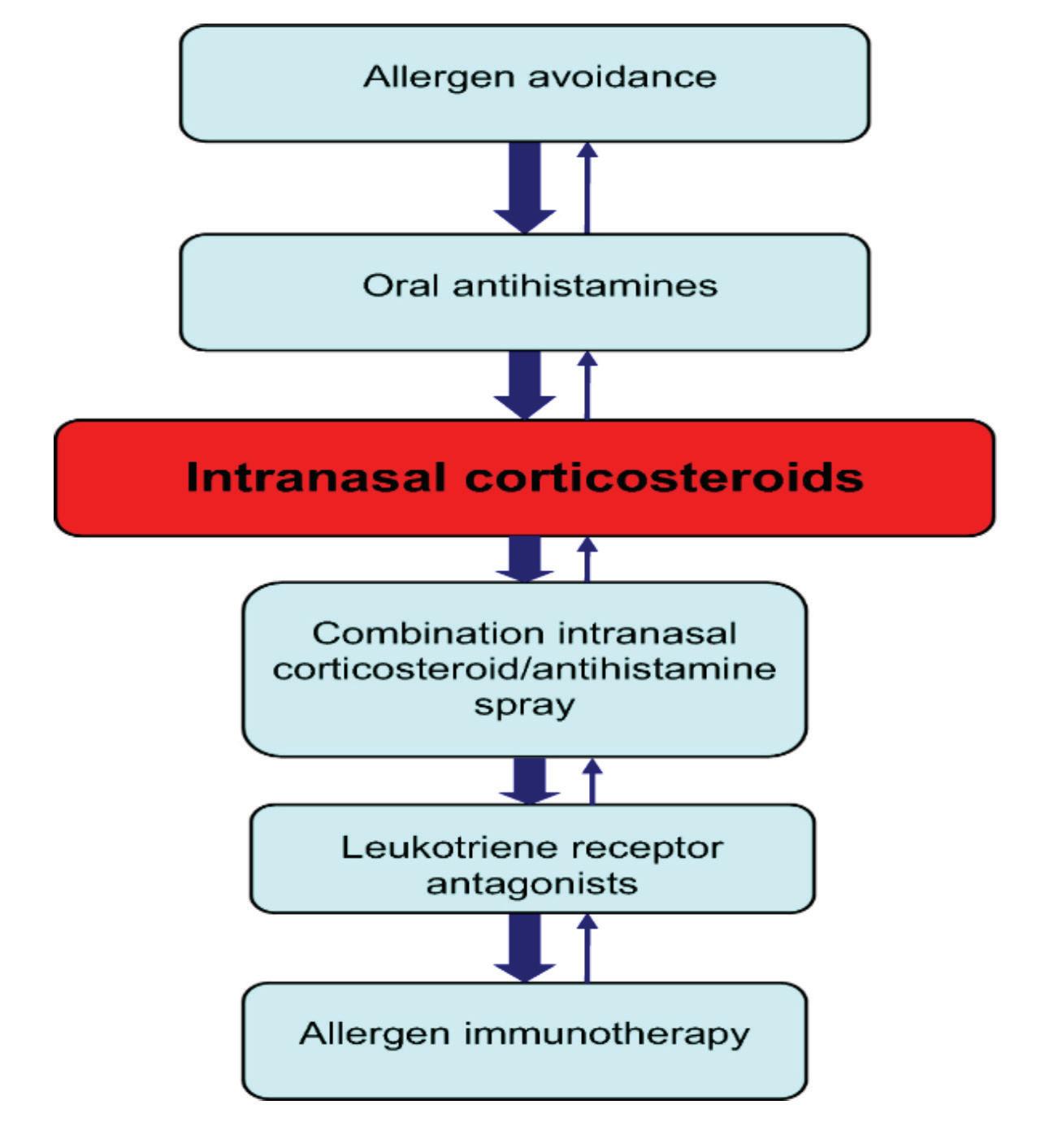

AR adversely affects the daily living activities of nearly 1.38 million Irish people and affects up to 30 per cent of adults and 40 per cent of children in industrialised countries. Approximately 80 per Figure 1: Stepwise treatment approach to allergic rhinitis component of a systemic airway disease involving the entire respiratory tract. Allergen provocation of the upper airways not only leads to a local inflammatory response, but may also lead to inflammatory processes in the lower airways, and this is supported by the fact that rhinitis and asthma frequently co-exist. AR affects 60-to-80 per cent of people with asthma. Some patients have AR alone, whereas others have AR and asthma with or without other allergic manifestations, although few patients have asthma alone. Although it is well established that rhinitis can lead to asthma, the exact phenotype of AR prone to developing asthma is still unclear. It is possible that poly-sensitised individuals can more commonly develop asthma.

Traditionally categorised as seasonal or perennial, AR is better classified according to symptom duration (intermittent or persistent) and severity (mild, moderate or severe). ARIA (Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma) guidelines classify AR as intermittent or persistent depending on the duration of symptoms, with persistent rhinitis occurring for more than four days a week for more than four weeks in a row, and as mild, moderate or severe, depending on whether sleep and daily activities are affected or whether symptoms are troublesome ( Figure 2).

Risk factors for AR include antibiotic use, inhalant and occupational allergens, as well as genetic factors. Common triggers include dust mites, animal allergens, pollens, spores, and moulds.

Pathophysiology

AR is an autoimmune condition and symptoms occur when the immune system overreacts to a normally harmless substance such as pollen. When the body encounters an allergen, cells in the lining of the nose, mouth and eyes release histamine – triggering symptoms of an allergic reaction. Allergic reactions do not occur the first time a person comes into contact with an allergen. The allergic immune response begins with a sensitisation phase when the patient that promote immunoglobulin E (IgE) production by plasma cells. Crosslinking of IgE bound to mast cells by allergens, in turn, triggers the release of mediators, such as histamine and leukotrienes, which are responsible for arteriolar dilation, increased vascular permeability, itching, rhinorrhoea, mucous secretion, and smooth muscle contraction in the lung. The mediators and cytokines released during the early phase of an immune response trigger a further cellular inflammatory response, which results in the recurrent symptoms that often persist.

Diagnosis

A thorough history and physical examination are important for establishing a diagnosis of AR. History should include questions regarding a family background of atopic disease, the impact of symptoms on quality-of-life and the presence of comorbidities, such as asthma, mouth breathing, snoring, sleep apnoea, sinus involvement, otitis media, and nasal polyps. Clinical history should note when and where symptoms occur and any exacerbating and relieving factors. Chest, ears, throat, abdomen and skin should be examined for other symptoms and a review of any treatments and their efficacy carried out. Testing for allergen-specific IgE using skin prick or blood tests to identity the allergen can support the diagnosis. Other tests may include a nasal endoscopy, nasal inspiratory flow test, and CT scan.

is first exposed to an allergen without experiencing clinical symptoms. In AR, numerous inflammatory cells, including mast cells, CD4-positive T-cells, B-cells, macrophages, and eosinophils, infiltrate the nasal lining upon exposure to an allergen. In allergic individuals, the T-cells infiltrating the nasal mucosa are predominantly Th2 and release cytokines, eg, interleukin [IL]-3, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13

Rhinitis has important co-morbidities. Asthma should always be assessed for in patients with AR and if needed an objective measurement, such as spirometry, carried out owing to the frequent co-occurrence of these disorders. Patients should also undergo ear inspection as otitis media with effusion may be a co-morbidity in children with rhinitis and in adults with severe forms of rhinosinusitis. The general examination should include skin examination for atopic dermatitis and assessment of thyroid function by checking for slow relaxation after the ankle jerk and for eye signs, such as puffiness, redness and/ or bulging (hypothyroidism) in patients