20 minute read

VIRTUAL ASTHMA AND COPD REVIEWS

Ruth Morrow

Respiratory Nurse Specialist. Registered Nurse Prescriber, Nurse Educator & Consultant

ADULT ASTHMA – DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT

The aim of this module is to explore the diagnosis and management of stable asthma in the adult person. The module will focus on symptoms, diagnosis, differential diagnoses and management of stable asthma

Setting the scene

Asthma affects over 380,000 people in Ireland. 7.1 per cent of Irish adults have asthma (www.asthmasociety.ie accessed 7th July 2020). In 2020, one person continues to die from asthma in Ireland every six days despite advances in knowledge of the mechanisms of asthma and pharmacology.

In 2019, the Asthma Society of Ireland published a report on the economic burden of asthma in Ireland. Easing the Economic Burden of Asthma – The Impact of a Universal Asthma Self-Management Programme is the first prevalence and impact assessment of asthma since 2001. The report, for the first time, confirms the enormity of the asthma burden and contains up-to-date figures on the number of people affected by asthma in Ireland. Previous estimates using the Quarterly Household National survey and other crude data, into the large-scale impact of asthma on the Irish healthcare system, grossly under-estimated the number of people with asthma in Ireland. 2017 saw 2.4 million GP and 625,000 practice nurse asthma consultations respectively, 421,000 specialist visits, 133,000 emergency department visits and 8,000 hospital admissions. One person dies every five days from an acute asthma attack and there is one attendance at emergency departments every four minutes by a person with asthma. The annual economic burden of asthma is a staggering €472million. Some other statistics from the report include: ▸ 890,000 people in Ireland experience asthma at some stage of

their life. ▸ €1,242: The annual average cost of asthma per person. ▸ 1 in 13 people in Ireland currently have asthma. ▸ 1 in 10 children currently have asthma ▸ 1 in 5 children experience asthma at some stage in their life. ▸ Compared to 14 other European countries: Ireland had the highest death rate from asthma in 2015. ▸ The average number of work days missed every year due to asthma is seven ▸ The average number of school days missed every year due to asthma is five ▸ Ireland had the second highest rate of asthma hospital discharges in Western Europe in 2016 ▸ 40,593: The number of children registered under the Asthma Cycle of Care programme ▸ 2.68 days: Average length of stay with an asthma hospital admission Asthma is a condition that can be treated effectively and most patients can obtain good control through optimal use of their medication and appropriate management plans. Optimally controlled asthma includes: ▸ little or no use of reliever inhaler ▸ have no night-time or daytime symptoms ▸ have productive physically active lives ▸ have near normal lung function ▸ avoidance of serious attacks

(GINA, 2020) A copy of the report can downloaded here https://www.asthma.ie/docu

ment-bank/easing-economic-burdenasthma-report

Signs & Symptoms

The symptoms of asthma include wheezing, coughing, shortness of breath and chest tightness following exposure to allergens. These symptoms are variable and usually troublesome at night or early morning. To make a diagnosis of asthma patients should have at least two of these four symptoms. Symptoms are variable and may occur or worsen in a seasonable pattern. The patient may also have eczema and hay fever. A positive family history of asthma or other atopic conditions may also be present. The patient may describe their symptoms becoming worse when exposed to certain trigger factors.

Trigger factors

Trigger factors for asthma are individual to each patient and can include smoking, house dust mite, respiratory tract infections, exercise, changes in temperature, fumes, occupation agents, fog, stress, hormones, emotion and certain medications (aspirin, beta-blockers and NSAIDs). The list of possible trigger factors can be lengthy and it may take the patient some time before they can identify their trigger factors.

Asthma Phenotypes

Traditionally asthma has been divided

Multiple Choice Questions

Q1: The pathological changes which occur in the airways as a result of asthma are: a) hypertrophy of the bronchial walls b) contraction of the muscle layer c) infiltration of inflammatory mediators d) all of the above

Q2: A diagnosis of asthma is made based on: a) Chest x-ray b) Chest examination c) History taking, chest examination and spirometry with reversibility testing d) Peak flow reading

True/false questions

Q3: The diagnosis of asthma involves carrying out spirometry only

Q4:Medications that may cause the onset of asthma include beta-blockers, NSAIDs and aspirin into allergic or non-allergic asthma. Other terms which have been used include eosinophilic or non-eosinophilic. As research has developed, asthma is now classified as T2 or nonT2 asthma and treatments have developed as a result.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of asthma is made by the patient’s symptoms and medical history with the measurement of lung function using spirometry (GINA, 2020). If the patient has a history of any of the following then asthma should be suspected: ▸ Cough which is worse at night ▸ Recurrent wheeze ▸ Recurrent difficulty breathing ▸ Recurrent chest tightness

History taking & assessment:

An accurate and complete history is essential and should include the following: ▸ Personal history – recurrent chest infections? asthma as a child?, smoking history including passive smoking?, allergies to medications? Is the person taking any medications for other conditions such as hypertension, diabetes etc? ▸ Family history- asthma? eczema?, allergic rhinitis? urticaria? ▸ History of current symptoms- what symptoms of asthma is the person experiencing? What triggers the symptoms? Has the person missed any days of work with these symptoms? Symptoms of allergic rhinitis?

How many acute episodes has he/she had?

Have these acute episodes necessitated hospital admission, nebulisations or the use

of oral steroids? Have they ever been prescribed inhalers before and if so what were they? ▸ In relation to asthma symptoms three questions should asked at every visit. Does the person experience wheezing, coughing, shortness of breath or chest tightness during the day? Does the person experience these symptoms at night? Does the person experience these symptoms on exercising? If the answer to any of these questions is yes then the frequency of asthma symptoms needs to be ascertained.

Spirometry is the preferred method for measuring airflow obstruction with reversibility to establish a diagnosis of asthma. An increase in FEV1 of 12 per cent or 200mls 15 minutes after inhaling a bronchodilator demonstrated airflow limitation consistent with asthma (GINA, 2020). However, not all patients with asthma will have reversibility and repeated tests are advised.

Peak flow measurements can be used if the patient is unable to perform spirometry and are very useful as a monitoring and educational tool for patients. An improvement of 60l/min or greater than 20 per cent post bronchodilator or a greater than 20 per cent in diurnal variation (with twice daily readings, more than 10 per cent) suggests a diagnosis of asthma (GINA, 2020).

FENO testing is associated with levels of blood and sputum eosinophils.

FeNO levels are higher in:

Onset

Inflammation

Response to inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) Triggers

T2 Asthma, high eosinophilic asthma

Previously known as allergic asthma

Usually in children linked to atopy but will be present in adults who have had asthma as a child

High levels of eosinophils in sputum and blood

Responds very well to ICS

Dust, animal hair and dander, pollens

Non-T2 Asthma or non-eosinophilic asthma

Previously known as non- allergic asthma

Usually in adulthood

Low levels of eosinophils in sputum and blood. Inflammation tends to be neutrophilic Poor response to ICS and usually require high doses of ICS

Infections, smoking, pollution, hormones, exercise

Table 1: Asthma phenotypes

▸ Asthma that is characterized by Type 2 airway inflammation ▸ Non-asthma conditions, eg, eosinophilic bronchitis, atopy, allergic rhinitis, eczema ▸ Late response to allergen (after 24 hours) FeNO levels are lower in: ▸ Smokers ▸ Bronchoconstriction ▸ Early phases of allergic response ▸ Some asthma phenotypes, e.g. neutrophilic asthma FeNO is increased or decreased in: ▸ Viral infections ▸ Response to ICS ▸ In adult steroid-naïve patients with nonspecific respiratory symptoms, FeNO >50ppb was associated with good shortterm response to ICS ▸ No long-term studies examining the safety of withholding ICS if FENO is low ▸ FeNO cannot be recommended for deciding against treatment with ICS FENO testing can be viewed here: https://youtu.

be/c8e-vmZBWy8

Measure of allergic status (IgE, RAST, skin allergy tests) can be useful in identifying risk factors. The presence of allergies, eczema and allergic rhinitis increase the probability of a diagnosis of asthma. In secondary care, histamine and metacholine challenges may also be carried out.

Challenges to the diagnosis of asthma include:

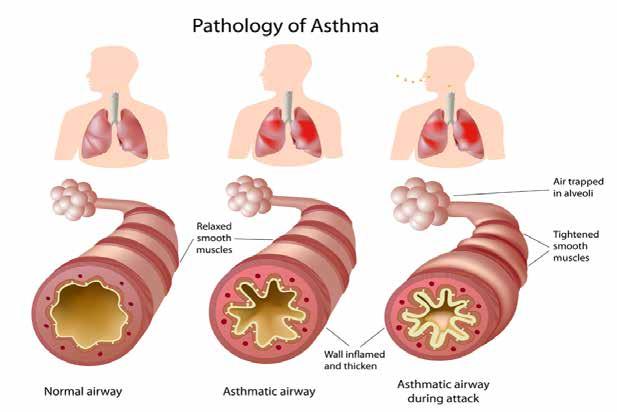

Figure 1

▸ Cough variant asthma – some patients have chronic cough which occurs at night.

Evidence of lung function variability and airway hyper-responsiveness are important to determine the presence or absence of asthma ▸ Exercise induced bronchoconstriction – for some patients, physical activity may be the only trigger for asthma. An eight minute running challenge can confirm an asthma diagnosis (GINA, 2020) ▸ Asthma in the elderly can be difficult to determine as there are several complicating factors such as poor perception of symptoms, reduced expectations of mobility and activity and the possibility of other conditions such as COPD, heart failure, lung cancer, and TB to mention but a few. ▸ Occupational asthma requires a defined history of occupational exposure to sensitizing agents, an absence of asthma symptoms prior to employment and a documented relationship between symptoms and the workplace. The patient should be asked to maintain a peak flow diary while at work and while away from work to help determine the diagnosis. The opinion of an occupational respiratory physician should be sought.

Assessment of symptoms

All patients should be assessed and their level of control established. In general, good clini

Answers Q1: D

The clinical features of asthma (wheeze, cough, shortness of breath and chest tightness) result from changes in the airways as a result of abnormal sensitivity called bronchial hyper-reactivity. The muscle of the bronchial walls becomes hypertrophied causing occlusion of the airway resulting in contraction of the muscle causing bronchospasm. Secondly, in the mucosal, submucosa and smooth muscle layers of the bronchi and bronchioles inflammatory cells infiltrate. Eosinophils, neutrophils, macrophages, mast cells and plasma cells are found in varying numbers. All of these cells contain chemical mediators that produce the “asthmatic response”. With the increase in secretions, plugging of the smaller airways result.

Asthma is a condition where not only bronchospasm occurs but muscle constriction, mucosal swelling and an increase in secretions in the lumen in the airways.

Q2: C

Chest x-ray should only be considered for patients who present with atypical symptoms and those who fail to respond to inhaled therapy. Most people with asthma do not demonstrate any abnormality on their chest x-ray. Hyperinflation may be seen on x-ray when the patient is experiencing an acute asthma attack.

Q3: False

The diagnosis of asthma involves full history taking including family history, personal medical and surgical history, current medications, assessment of trigger factors, clinical examination and spirometry/PEFR (GINA, 2020)

Q4: True

Patients on NSAIDs. Aspirin and betablockers may be predisposed to developing asthma. Medication history should be explored when assessing patients.

Multiple Choice Questions

Q5: The differential diagnoses for asthma include: a) COPD b) Inhaled foreign body c) Hyperventilation d) all of the above

Q6: Identification and management of allergic rhinitis is required because: a) the presence of these conditions may exacerbate asthma b) the presence of these conditions has no effect on asthma c) these conditions rarely present in people with asthma d) there is no licensed treatment for asthma and allergic rhinitis

True/false questions

Q7: Risk factors for asthma include family history of asthma and atopy

Q8: 10% reversibility to Salbutamol is positive diagnostic test for asthma

Figure 2: Asthma Control Test

cal control of asthma leads to reduced risk of exacerbations (GINA, 2020). There are a number of well validated tools available which can assist the practice nurse in assessing asthma control such as the Asthma Control Test (www. asthmacontrol.com). The maximum score is 25 which indicates good asthma control. A score of 19 or less indicates poor asthma control. GINA (2020) recommends using the Royal College of Physicians provide 4 item tool to assess the patient’s asthma over the previous four weeks. If the patient answers “yes” to all these questions, their asthma is not controlled, “no” to all questions, their asthma is well controlled and if they answer “yes” to one or more, their asthma is partly controlled.

Management of asthma

The treatment and management of asthma should incorporate the following elements: ▸ Education on the disease process ▸ Management of trigger factors ▸ Medication management – actions, delivery, side effects ▸ Asthma Action Plan ▸ Management of acute episodes of asthma

The goal of asthma management is for the patient to be optimally controlled on the minimum amount of medication. GINA (2020) provides healthcare professionals with a management approach based on control (Figure 2 & 3). This assists health professionals with the titration of medications using a step down or step up approach in attempt to achieve this goal.

The cornerstone of asthma treatment is inhaled therapy as medication is directly targeted at the airways and therefore, is more effective. This also limits the amount of systemic absorption and reduces side effects. Patients should be commenced on the appropriate step of the treatment guidelines (GINA, 2020). Each patient is assigned to one of five treatment steps and patients may move up or down the steps depending on symptoms and the amount of reliever therapy being used (see figures 2 & 3). Inhaled glucocorticosteroids are the cornerstone of asthma treatment and are the most effective controller medications available (see table 2).However, there are additional oral medications such as leukotriene receptor antagonists which can be added on and are very useful in patients who have an allergic component to their asthma, experience cold air bronchoconstriction and have exercise induced symptoms. These medications are also licensed for use in allergic rhinitis, a condition which 85 per cent of people with asthma also have.

The Global Initiative for Asthma Management and Prevention (GINA) (2020) recently updated their strategy which outlined significant changes to way healthcare professionals (HCPs) manage asthma in adults and adolescents. The changes recognise a real sea change in the use of short acting bronchodilators (SABA) and the introduction of combination therapy of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and long-acting bronchodilators (LABA) as “a needed therapy” at Step 1 and as a maintenance therapy at Step 2. Using a combination therapy as an “as-needed” therapy will require a significant change in the mindset of HCPs given that we having been using SABAs for the last 50 years to relieve asthma symptoms.

Why this change?

Inhaled SABA (Salbutamol, Terbutaline) have been first-line treatment for asthma for 50 years. Traditionally asthma was thought to be a disease of bronchoconstriction and therefore SABA was the drug of choice. Added to this, rapid relief of symptoms, reliance on, patient satisfaction and their low cost have meant that

SABAs were widely used, overused and over-relied upon. The perception by patients that their reliever “gives me control over my asthma”, so much so that they often don’t see the need for other treatment. However, research over the past number of years has shown that regular and frequent use of SABAs decrease bronchoprotection, increase rebound hyperresponsiveness, and decrease bronchodilator response (Hancox, 2000). Patients with apparently mild asthma are at risk of serious adverse events such as near fatal asthma, acute asthma and death from asthma. Regular or frequent use of SABAs are also associated with Increased allergic response and increased eosinophilic airway inflammation (Aldridge, AJRCCM 2000). Patients who get three or more canisters of SABA per year (average 1.7 puffs/day) are associated with higher risk of attendance to the emergency department (Stanford, AAAI 2012) and patients who receive 12 or more canisters per year are associated with higher risk of death (Suissa, AJRCCM 1994).

Combination therapy “as-needed”

In their review of the literature, GINA found no evidence to support a Step 1 SABA-only approach. The lack of evidence for SABA-only treatment contrasted with the strong evidence for safety, efficacy and effectiveness of the treatments recommended in Steps 2-5 of the strategy i.e. ICS and ICS/LABA. For safety, GINA no longer recommends SABA-only treatment for Step 1. This decision was based on evidence that SABA-only treatment increases the risk of severe exacerbations, and that adding any ICS significantly reduces the risk. It is now

recommended that all adults and adolescents with asthma should receive symptom-driven or regular low dose combination LABA/ICScontaining controller treatment, to reduce the

risk of serious exacerbations (GINA, 2019). Patients who have symptoms more than twice a month should be prescribed ICS/LABA twice daily (Step 2-5) and patients who have symptoms less than twice a month should use ICS/ LABA on “an as-needed basis” (Step1). Daily ICS is no longer listed as a Step 1 option which was included in GINA 2014-18 as it has a high probability of poor adherence. It is now replaced by a more feasible as-needed controller option at Step 1. The rationale for this using low dose ICS/LABA as needed has been shown to reduce exacerbations. Indirect evidence from SYGMA 1 of large reduction in severe exacerbations vs SABA-only treatment in patients eligible for Step 2 therapy (Bateman,2018, O’Byrne, 2018). Patients should be offered self-management plans with instructions on how to adjust their medications in response to worsening symptoms and/or worsening PEFR. An example of a self-management plan is available on www. asthmasociety.ie.

The non-pharmacological management of asthma includes management of trigger factors, smoking cessation, management of obesity and annual influenza vaccination. Gastro-esophageal reflux can worsen asthma symptoms. Treatment of reflux may improve asthma symptoms. Hormones can also play a significant role in asthma control. Some patients will experience worsening of their asthma symptoms pre-menstrually or during menstruation. During pregnancy, asthma control may improve, deteriorate or stay the same as pre-pregnancy. Asthma may also develop in women who are menopausal.

Inhaled glucocorticosteroids in asthma

Inhaled glucocorticosteroids are the cornerstone of asthma treatment. The aim of which is to reduce the inflammatory process in the airways. Table 2 outlines the treatment options available to patients. It is recommended that if patients use their bronchodilator more than twice a week, then they should be commenced on inhaled steroid therapy.

Adherence with medication regimes

One of the biggest challenges in asthma management is adherence to medication, as many patients may be asymptomatic and therefore “don’t feel the need to use their medication daily”. Exploring the patient’s beliefs and attitudes can be useful in determining a rationale for non-adherence to their medication regime. Saving medication until it is needed, fear of becoming addicted or the health professional didn’t listen are amongst reasons given by patients in the recent INCA study (Sulaiman et al, 2014). In the current climate, cost is a significant factor even for the person who has a medical card and should not be overlooked.

Two proven ways to address non-adherence are

Answers Q5: D

The differential diagnoses for asthma include COPD, cardiac disease, tumour, bronchiectasis, foreign body, interstitial lung disease, pulmonary emboli, aspiration, chronic cough syndrome, vocal cord dysfunction and hyperventilation. Referral for specialist opinion is indicated when the diagnosis of asthma is unclear and when unexpected clinical findings such as crackles, cyanosis, clubbing are found on clinical examination. Should occupational asthma be suspected the patient should be referred for further investigation and management. Persistent shortness of breath, weight loss, persistent chest pain, non-resolving pneumonia and persistent cough all warrant specialist opinion.

Q6: A

Allergic rhinitis is present in 85% people with asthma and needs be addressed and managed effectively as it can cause worsening of asthma symptoms (ARIA, 2007). Patients should be questioned about symptoms of itchy watery eyes, rhinorrhea, sneezing, nasal obstruction, nasal pruritus and conjunctivitis. Leukotriene receptor antagonists are licensed for use in both allergic rhinitis and asthma and are a useful treatment option for these patients. However, they are effective in only 50% of patients and should be discontinued after 6 weeks if they are ineffective. Side effects include sleep disturbance and nightmares and patients should be counselled about these.

Q7: TRUE

A family history of asthma or other atopic condition such as eczema or allergic rhinitis inn first degree relatives contribute to a diagnosis of asthma.

Q8: FALSE

An increase in FEV1 of 12% 15 minutes after inhaling Salbutamol 400mcg is positive for asthma (GINA, 2020).

Drug Name

Beclomethaone Becotide™ Beclazone™ Qvar™ Budesonide Pulmicort™ Novolizer budesonide™

Fluticasone Proprionate Flixotide™

Fluticasone fuorate Relvar™

Mometasone Asmanex™

Clicesonise Alvesco™

Prednisilone Prednesol™ Deltacortril Enteric™

Formulation

Inhaler

Inhaler, respules

Inhaler, nasal preparation

Inhaler

Inhaler

Inhaler

Tablet, intravenous/ intramuscular preparation, soluble preparation

Dose Frequency

Twice daily but can be used up to four times daily

Twice daily but can be used up to four times daily

Twice daily

Once daily Once daily

Once daily

Once daily

Side Effects

Oral candidiasis, dysphonia, pharyngitis

Availability As Combination Therapy

No

Yes – with Formoterol (Symbicort™)

Yes – with Salmeterol

Yes with Vilanterol

No

No

Prolonged use can cause: Weight gain, hypertension, diabetes, changes in mood, moon face, hirsuitism, depression, adrenal suppression No

Table 2: Inhaled glucocorticosteroids for asthma (GINA, 2020)

shared decision-making between the health professional and the patient and motivation interviewing. Using motivational interviewing, the health professional can assess the individual’s likelihood to adhere to their medication or to non-pharmacological interventions.

Asthma Safety Care

The National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD) in the UK (2014) showed that asthma deaths were linked to overuse of and over reliance on Salbutamol. The Asthma Society of Ireland launched the Asthma Safety Care campaign early in 2020. According GINA, using three or more reliever inhalers a year indicates a person is at risk of an asthma exacerbation while the use of twelve or more a year is an indication someone is at risk of an asthma-related death. The Asthma Ruler can be used to assess if a patient is over reliant on their Salbutamol inhaler and be accessed on line here: https://www.pcrs

uk.org/resource/asthma-slide-rule

Patient education

Patients require ongoing education and support in self-managing their asthma. Regular review of their Asthma Action Plan to ensure it is up to date and reflects the patient’s lifestyle. Education should include:

▸ Managing Acute Asthma - patients should be educated in the 5 Step Rule for managing acute asthma attacks which is available on www.asthma.ie ▸ Management of trigger factors ▸ Inhaler technique ▸ Adherence to medication ▸ Use of Asthma Action Plan ▸ Vaccinations

Conclusion

This e-learning module has focused on the diagnosis and management of stable asthma in the adult. The differential diagnosis of asthma, pharmacological treatment, non-pharmacological treatment and the importance of adherence with medication have been discussed. The significant changes to the management of asthma have also been discussed. The importance of the patient being involved with decisionmaking in relation to medication has also been addressed.

Further reading

▸ Asthma Society of Ireland, 2019,

Easing the Economic Burden of

Asthma – The Impact of a Universal Asthma Self-Management

Programme ▸ Asthma Control in General Practice Adapted from the GINA

Global Strategy for Asthma Management & Prevention, 2012,

Irish College of General Practitioners ▸ Global Initiative for Asthma, 2020, Pocket Guide for Asthma

Management and Prevention (For

Adults and Children over 5 Years) ▸ Laube BL, Janssens HM et al, 2011,

What the pulmonary specialist should know about the new inhalation therapies, European Respiratory Journal, 37: 1308-1331

REFERENCES ON REQUEST 5 step rule: how to deal with an asthma attack 1. Sit up and stay

calm, do not lie down

2. Take slow steady breaths 3. Take 1 puff of reliever inhaler

usually blue every minute use a spacer if available. People aged 6+:up to 10 puffs in 10 mins. Children under 6: up to 6 puffs in 10 mins 4. Call 112 or 999 if your symptoms do not improve after 10 minutes 5. Repeat step 3 if an ambulance has not arrived in 10 minutes

If someone has an asthma attack

Do not leave them on their own.

Extra puffs of reliever inhaler (usually blue) are safe.