4 minute read

Overwhelmed

Baby botox, luxury penthouses, mass shootings, New York Fashion Week, Italy travel plans, natural disasters, and a $2,000 Shein haul. These were all videos I saw in back to back succession on my “For You Page” via TikTok. As most people feel after spending hours scrolling, my attention span was fried, and I felt completely overwhelmed.

TikTok, along with Instagram, are two of the most popular social media platforms for Gen Z. Their algorithms purposefully promote content that leaves its audience more dissatisfied than before they opened the app. This is intentional. An unhappy person with lower self-esteem is more likely to purchase a product advertised to them. Social media platforms seeking to maximize profits have an invested incentive in recommending content that will either create new insecurities in consumers or exaggerate existing ones. The two common insecurities that algorithms target are wealth and attractiveness, often prioritizing content made by above-average looking young people who come from higher-income backgrounds. The average person will (consciously or subconsciously) come to the conclusion that they are below-average in either department, and they will seek to “remedy” this problem. Brands can then swoop in to address insecurities held by consumers, offering a product that will, in some way, account for their manufactured problems.

Advertisement

The fashion industry has taken social media by storm with immensely successful advertising campaigns, specifically in terms of influencer marketing. Social media’s fastpaced cycles have taken trends from seasonal cycles to weekly cycles. Consumers, primed by their algorithms to be ready to

By Devon Middlebrook

purchase, are often influenced by brands who take advantage of different aesthetic categories on social media. New aesthetics prop up constantly, creating new trends which can be capitalized on, such as Balletcore, which created a new market demand for ballet flats, hair ribbons, shrugs, leg warmers, and mini pleated skirts. Popularized items and themes from luxury designer brands Miu Miu and Maison Margiela trickled down to mid-tier brands such as Urban Outfitters and Free People and finally to knock-off producers Boohoo, Amazon, and Shein.

Fast fashion corporations step in to meet consumer demand, as they have the capital to produce trends and bring them to market in a short amount of time. Shein, for example, became the largest fashion company in 2022, with revenues reaching 30 billion dollars, leading the company to receive a valuation of 100 billion dollars. However, this mode of consumption has had disastrous effects on the environment, as fashion now represents the third largest polluting industry and accounts for 10 percent of greenhouse gas emissions. In addition, the products people receive are often low-quality, which, in the best case scenario, need to be replaced shortly after purchase, or in the worst case scenario, contain harmful or toxic chemicals (such as PFAs).

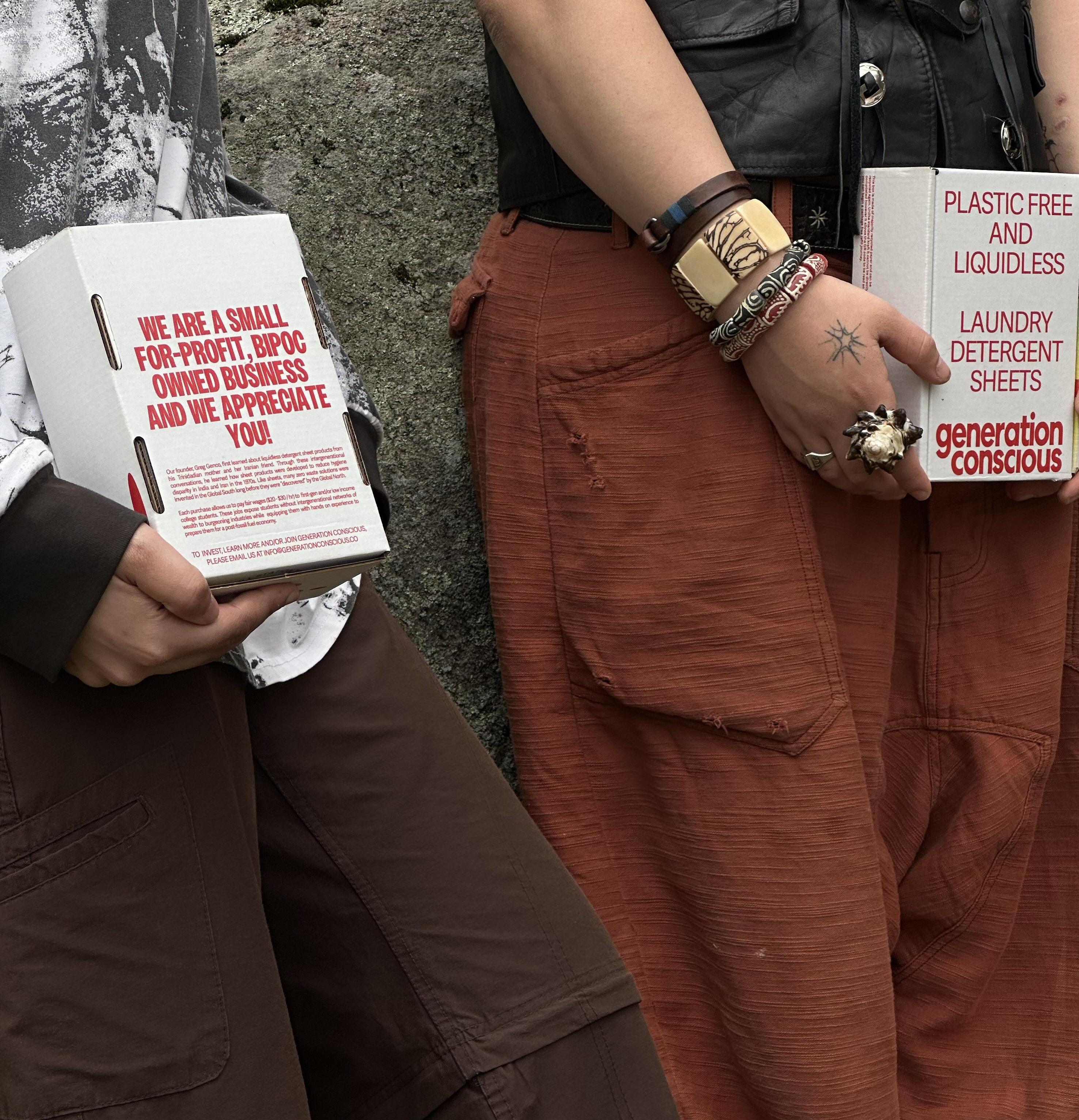

Now, fast fashion’s negative impact on the world has come into popular debate. Harsher critiques of consumerism have given way to more palatable solutions. Instead of purchasing from large conglomerates who prioritize selling high quantities of cheap goods, it is perceived as more ethical to purchase from smaller, higher-cost brands at lower quantities. Those who continue to purchase from fast fashion conglomerates are seen as uncaring, immoral, and as part of the problem. But are these smaller, more environmentally conscious brands a solution to the sustainability problem in the fashion industry?

Green-washing, the practice of marketing products as having a low or positive impact on the environment, has become a popular strategy for brands looking to exploit this new group of consumers. The LAbased clothing brand Reformation primarily advertises to the environmentally-conscious, with its tagline “Being naked is the #1 most sustainable option. We’re #2.” While the brand is certainly more sustainable than Shein and operates at a much smaller scale, both companies mass produce large quantities of clothing made up of synthetic fabrics. Thrifting, or purchasing second-hand clothing from apps such as Depop (which is immensely popular with Gen Z), has been popularized as a more sustainable alternative. While consumers are no longer directly purchasing from small brands or large corporations in attempts to be more sustainable, it is not without its own drawbacks. With increased amounts of people sourcing clothing from charity/thrift outlets, in particular those who make a living off re-selling second hand fashion online, prices have been raised and items are increasingly picked over. This creates a problem for those who depend on thrift stores, which have historically provided an affordable option for clothing purchases. Additionally, purchasing items on second-hand apps typically requires the items to be shipped, which increases carbon emissions which inherently contributes to climate change.

In a capitalist society, it is impossible to not be a consumer in some aspects. However, we can control how much we choose to participate in consumerist culture. There are two main aspects we can focus on. The first component is combatting personal insecurities, which can be as simple as limiting social media usage or quitting social media entirely. This is easier said than done, as many people (myself included) are dependent on social media for social connections or are worried about missing out on trends. It is important to recognize that keeping up with trends does not mean one is fashionable, or that awareness of micro-trends is even necessary. The second aspect is to develop a strong sense of personal style that is independent of the current trend cycle. Take inventory of items you already own, and note which clothing items you find yourself gravitating to the most and the least. This will help you understand how to style what you already own. When it comes to purchasing new items, try to do so mindfully. It is important to do research on the product you are purchasing, specifically where and how it is manufactured, what types of fabric/material it is made out of, and the item’s practicality. This is a nuanced discussion, and everyone’s approach to the aspect of sustainability is different, but our behavior as American consumers can not continue on the path it is on. The intersection of social media and the fashion industry has proven itself as a toxic one, for both us and the planet.