11 minute read

Early Craftsman of the Federal City

Thomas Saharsky Federal Lodge No. 1

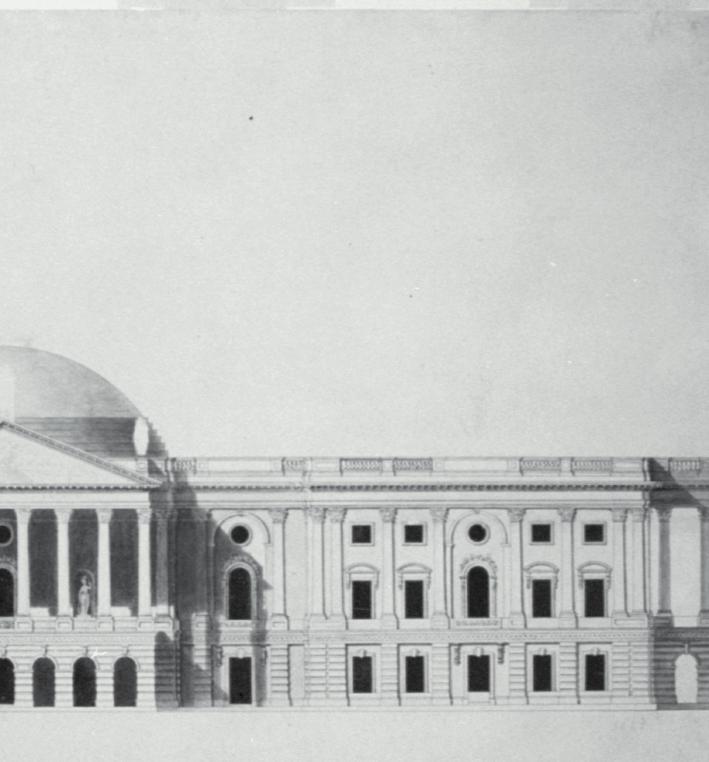

East elevation of the Capitol, drawn by WIlliam Thornton ca. 1796

Advertisement

Worshipful Brother James Hoban is popularly known as the Architect of the White House and Federal Lodge No. 1’s charter Master. While Hoban has earned the distinction of building one of our nation’s most important landmarks, he did not perform this duty alone. In fact, he was joined by a motely crew of carpenters, engineers, house joiners, stonemasons, blacksmiths, and doctors, some of them Freemasons, who all helped bring his vision to reality. It might be a further surprise to know that these craftsmen’s lifestyle and operative traditions also had a significant impact on early Freemasonry in the District of Columbia.

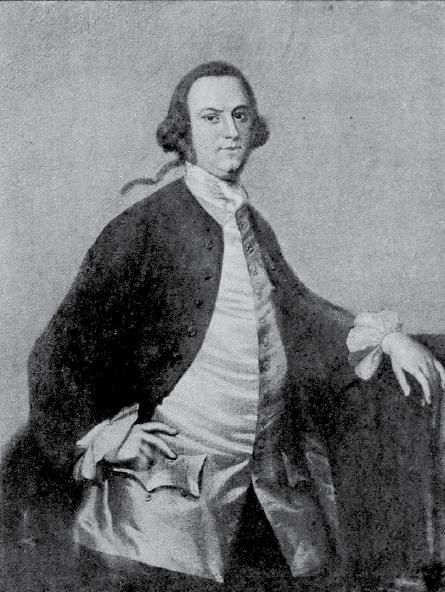

The task of erecting the nation’s early public buildings fell onto the District of Columbia’s first three Commissioners: Thomas Johnson (a judge and first governor of Maryland), Bro. Daniel Carroll (plantation owner and member of the first Continental Congress), and Bro. David Stuart (a physician, relative of George Washington by marriage, and likely member of Alexandria Lodge No. 22). While Washington appointed the commissioners, his appointees had no formal background in urban planning or civil engineering. Moreover, they lacked even the general scope and broad understanding of how to prepare the land in order to shape it into a workable plan. While their outlines and ideas may have been enough for seasoned architects or master stonemasons to conjure into completion, they were definitely neither.

So, the Commissioners were desperate to bring in professional and administrative personnel that could direct the day-to-day operation, anticipate seasonal needs, and subcontract the transportation of stone and wood to the new Federal City. Additionally, they needed teams of unskilled and semiskilled of laborers who could construct the President’s Mansion, office buildings, and the Capitol.

What most don’t realize is that they just didn’t start by building these buildings as if they found and bought a lot today, drew up the plans, and hired a contractor. They had to do literally everything from scratch, including sourcing, gathering, and transporting construction materials to the site. For example, the commissioners bought a quarry, found labor, quarried the stone, moved the stone to a wharf (which had to be built), shipped the stone via schooners to another wharf (which also had to be built), and then carted the stone or floated it in scows to the jobsite. In the city, they walked-off the area, marked the roads, got stone and leveled dirt for streets and roundabouts, set up a processing site including rubbish piles, set up additional markers for timber transportation lines, walked off lots for future sales, built temporary housing, and then had to account for all the secondary supplies they needed like bread, meat, and tools. This was all done with paper and pencil, without the assistance of even the Postal Service (which wouldn’t come until the early 1800’s). In fact, all of life in the 1790’s was brutal. The earliest brick buildings were reserved for leadership like architects, the Commissioner’s department, or the surveying department. Most of the actual workforce lived on, or near, the jobsite in temporary housing which consisted of shacks, shanties, or makeshift buildings, until 1795 when it was outlawed by the Commissioners. Obviously, none of these structures had air conditioning in the oppressive summer and the winter necessitated a pause in almost all work except survival.

At the jobsite, the work was so physically straining that craftsmen likely rested, slept, and ate in shifts in the workshops and lodges. The typical diet provided by the government consisted of Indian meal, bread (contracted by Brother Andrew Estave), and a protein—usually beef or pork (in some cases contracted by Brother Middleton Belt).

Whiskey was the medicine of choice after a hard day’s labor, or

Bro. Daniel Carroll Dr. David Stuart Thomas Johnson

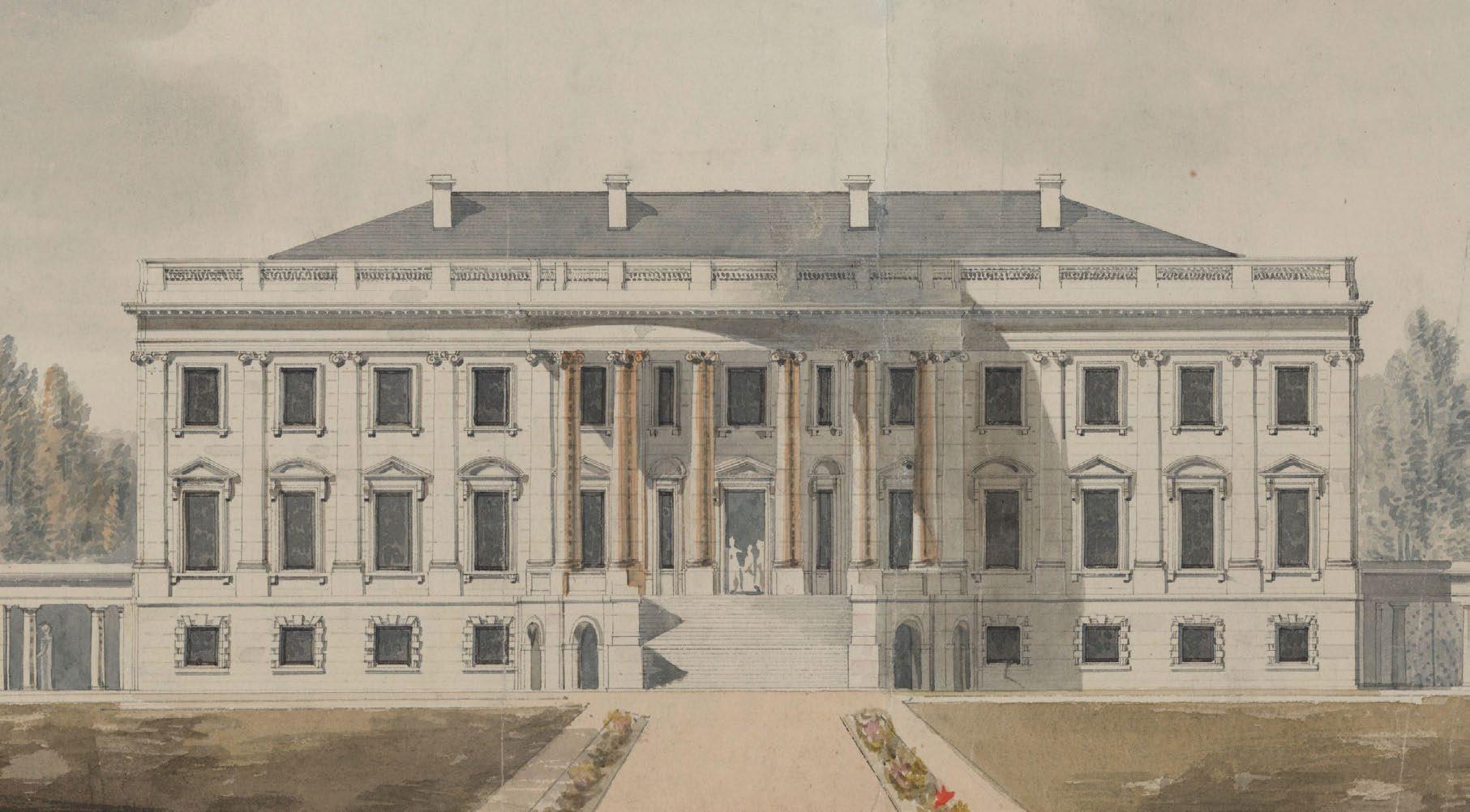

The White House ca. 1800

to subdue the weary toil of hard labor in the quarries prescribed by Brother Collen Williamson, the quarry owner. If you got sick, you were sent to the hospital where you met Brothers Dr. John Crocker or Dr. Fredrick May who bandaged people and sent them back to work. With no antibiotics, even a small cut could become infected and lead to amputation, or death. Vinegar was provided, and bloodletting was usually the cure for whatever ailed you. Conditions at the hospital were so poor and the humidity so bad, that Hoban requested that it be moved to a less swampy area. It was a far cry from what we expect form a healthcare facility today, but for all intents and purposes, it was free to those who worked at the federal city project and better care than the average American would have had in those days.

Between the low wages and the poor conditions, it was no wonder that the local woodworkers and stonemasons generally steered clear of the project, forcing the Commissioner to recruit immigrant and/or coerced labor. Interestingly though, there is evidence that suggests that at some point, certain slaves had more valuable experience, skill, or both, than the new hires at the President’s Mansion. The slaves who worked at the President’s House, and by extension the Capitol, were not unskilled by the second season of work and likely had the respect of their free coworkers, yet neither were they free. Specifically, we find that in one carpentry roll, a slave was compensated more than a non-slave for a brief moment. This compensation would have been based on something other than slave and non-slave status—a trait that looks more like the tacit tradition of the formal apprentice system than the contracted labor of today. So, the job site may have been the best opportunity during this slave-infested time to see a mutual respect of job skill, experience, respect for load, and performance, regardless of whether a man was free or a slave, until the Commissioners made a law or rule ensuring that slaves received less wages than the lowest non-slaves.

An example of this is Redmond Purcells, who headed a small group of slave sawyers at the President’s House. In keeping with the best operative tradition, these sawyers would have been considered as semi-skilled workers. Accordingly, they would have begun as a carpenter’s servants and set upon the pathway to becoming a Master Carpenters. Those in the worst position were the coerced laborers like those of prisoners or slaves who were assigned the most dangerous and physically difficult tasks of material processing and physical labor. But we know that with the work force as small as it was in the Federal city that individuals needed to be taught greater skills in order to work less supervised and to limit the rework of wood, stone, and other materials—all functions to keep costs and waste to a minimum.

The immigrant master craftsmen of Scottish and Irish descent, however, carried with them their building traditions, experience, and social provisions to the new world. They possessed a formula best described as “mastership” that allowed them to meet, act, and participate in a way they conveyed their knowledge from one employee to the next. Today, we see this as a tacit exchange of information; back then, it was called an apprenticeships system.

The Scottish operative masons also retained the ability, by extension of their charter, to meet at the jobsite and hold a social lodge, where experience-based learning systems and a socialized community laid the foundation for the other free-craftsmen to flourish.

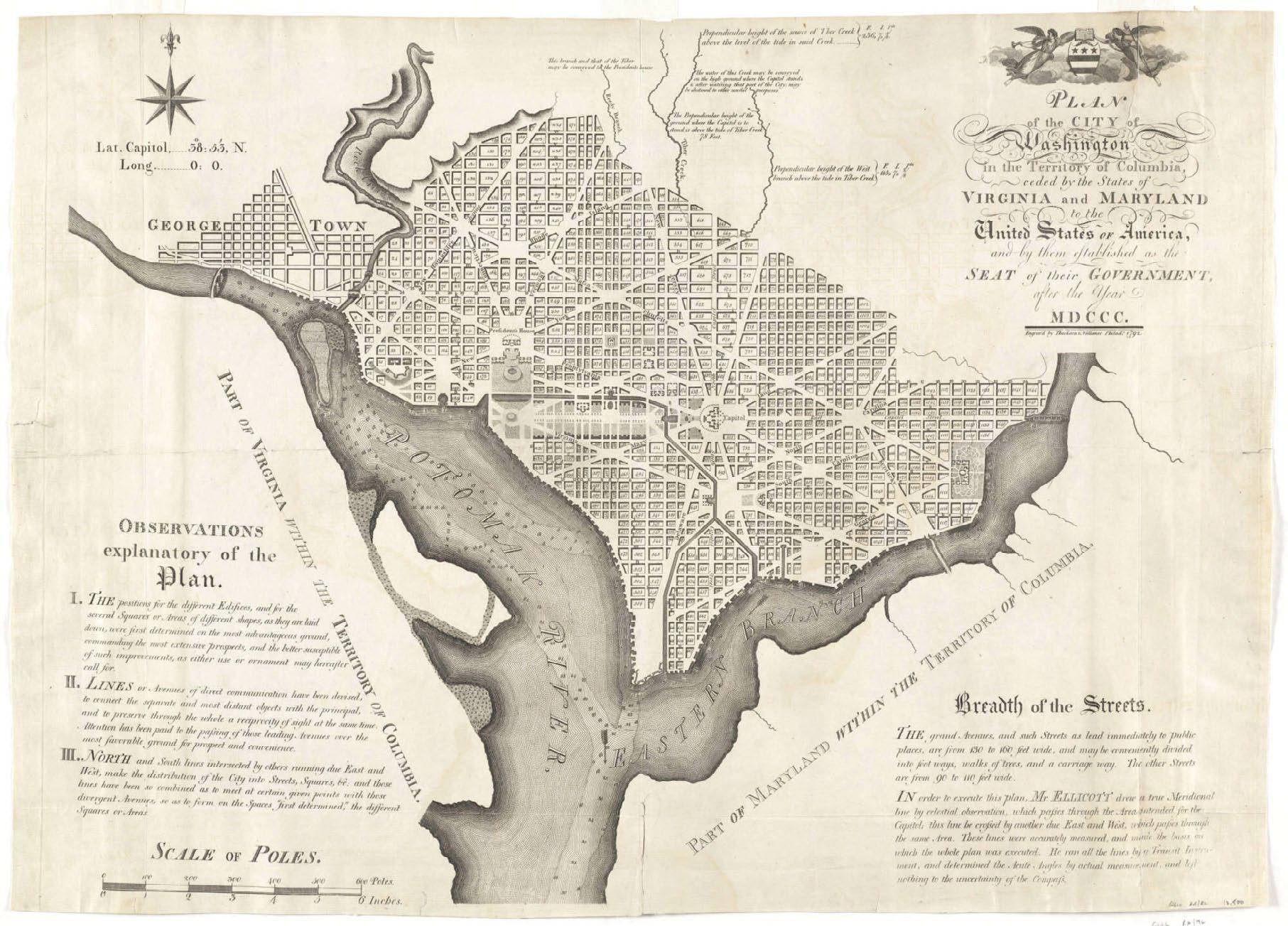

Ellicott’s plan for the Capital

The Irish immigrants carried a similar system of craftsmen that focused on the long-standing traditions of woodworking, which is generalized under the category of carpentry, but also included furniture makers, house joiners, and framers or engineers in the late 18th century. In fact, municipal records of the corporation of carpenters in 1564 is one of “four guilds in one”: carpenters, masons, joiners, and heliers (or tilers), who were granted a lease to meet at Taylor’s Hall on Wintavern Street, in Dublin.

Both of these traditions necessitated the inclusion of nontraditional, or speculative, persons found on the lodge rolls or in manuscripts (or contract agreements of labor), such as physicians, blacksmiths, supply liaisons, and transporters.

The progressive evolution of these operative lodges facilitates the transition from traditional lodges and their auxiliary social components, into a more socially conscious community. In England, these communities became the Nobles Sciences and Royal Arts, which then morphed into a gentleman’s organization called Freemasonry. This connection between the operative and speculative was mostly made of the gentry, but in Ireland and Scotland, the transition was more gradual and resembles the ancient process and evolution of the industry’s cross-pollination with the influx of speculative persons in the jobsite and auxiliary community lodges which worked with the town councils and other community assemblies to redress short comings in the work. Remarkably, these two overlapping philosophies of craftsmanship in Scotland and Ireland blended together to form the cornerstone of the first city Lodge of Washington, thus enshrining a thousandyear-old system of operative building within the permanent seat of government of the United States.

One may ask what evidence shows that these systems were carried into Washington City? Well, we find consistencies in the way and the manner in which stonemasons and carpenters were contracted and how they employed apprentices. Their contracts generally included food, drink, wages, and housing. In the cases of Collen Williamson, Master of Stonemasons, and his colleague, James Hoban, Architect-Superintendent, both received title, status, and compensation of the old-world systems which employed the titles Master Stonemason, Master of the Works, or Architect.

The apprentice is formally recognized in the minutes of the Commissioners. Collen Williamson, shortly after his employment,

was provided stone mason apprentices which endowed the stone workforce and industry with Scottish traditions. Later meeting minutes of the Commissioners indicated that James Hoban, Redmond Purcells, and Peter Lenox, adopted and retained carpentry apprenticeships. Redmond Purcells and Peter Lenox both became the “foremen” of carpenters respectively at the Capitol and President’s House at different times in their career. This allows us to equate a certain level of mastership with the ability to have an apprentice.

While the similarities between the old and new world contracts and the apprenticeship system cannot be denied, we must still adjust our context a bit. The Washington City project was an adhoc system, most likely assembled through some working tradition in order to lower cost and raise the efficiency of building the city quickly. Our best estimates indicate these craft traditions were carried over by the Scottish and Irish experts, who had trained workforces and built or designed buildings.

Another interesting point when comparing the old formal system with the informal building system in the United States was the lack of terminology and wages, indicating that the Commissioners were not familiar with the time-honored traditions of the building industry, but opted for a more American (new) way of doing things. Instead of the titles free-mason, hewer, house joiner, mason servant, fellow, master carpenter, and apprentice, we find a general definition of an overarching role, such as general labor, cutters, carvers, carpenters, and sawyers. Today, these general titles and wages define what we think their specialized skill sets and positions are and were with few exceptions.

The earliest speculative Lodge in the area that included the names of both Irish and Scottish masters on its rolls, was the now defunct Potomac No. 9. Their names are also attributed to the construction of the President’s Mansion during the cornerstone ceremony in 1792. But lackluster fundraising led them to generate sentiment by approving the use of cornerstone events to coincide with lot auctions, proving once again how difficult it was to get people interested in investing in the Federal City while it was effectively a transiting jobsite.

Informally, these operative craftsmen met to go over their planning of the next steps of the building process in an ad hoc theoretical lodge. They were formally indoctrinated into the speculative Freemason system on September 12, 1793, when Clotworthy Stephenson acquired a charter for Federal Lodge No. 15 just days before the Capitol Cornerstone event. The new Lodge emanated from operative traditions, tacit learning systems, and social lodges and their work was in applying and transmitting methods, practical norms, workplace efficiencies, industry innovations, habits, cultural designs, histories, mastership, and other social constructs. They were a living testament to the thousand-year-old tradition of

operative and non-operative members who congregated in lodges, workshops, and by effect constructed cities, castles, monasteries, tombs, and universities throughout the world.

Towards the end of the Residency Act (marked by the death of George Washington), the operative craftsmen began to disburse. They settled in the surrounding area or sought employment elsewhere. Accordingly, during this transition Federal Lodge began to morph into a purely speculative Lodge that resembled those in other surrounding communities. The members that remained in the city went on to become prominent figures in local leadership. Some were councilmen, local militia, members of the fire department, and advocates for Irish immigrants. Others were shopkeepers, and merchants, landlords, and religious leaders. Even up to the mid- to late- 19th century, Federal’s operative lodge members gravitated to the civic assemblies and judicial authority of the District of Columbia, while intersecting with the historical leadership of the other Potomac communities like Georgetown and Alexandria.

Today, much is owed to these relatively unknown men. Through their hard work, a capital city was erected in the swampy wilderness and speculative Freemasonry in Washington, D.C. was born along its side.