7 minute read

LINCOLN MEMORIAL REDEDICATION EVENT

In humble commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial, on Friday, June 10, 2022, the Grand Master of Masons of the District of Columbia, Most Worshipful Brother Daniel A. Huertas, alongside Most Worshipful Brother Anthony B. Corbitt, Grand Master of the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of the District of Columbia, gathered for a public Masonic procession at the Lincoln Memorial as accompanied by the United States Air Force Brass Quintet.

Led by the distinguished Bagpiper, Mr. Wayne Francis, representatives from each respective Grand Lodge, and accompanied by distinguished guests, processed from above the Reflecting Pool to the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, a most important symbolic Temple of Democracy for our Nation. With over 50 Brethren, and many invited guests present, the Colors were presented by the

Advertisement

Joint Armed Forces Color Guard, which was accompanied by the Pledge of Allegiance, as delivered by COL Worshipful Brother Robb Mitchell, US ARMY, Retired, and was followed by the National Anthem, as sung a capella by the renowned mezzo-soprano Ms. Anamer Castrello.

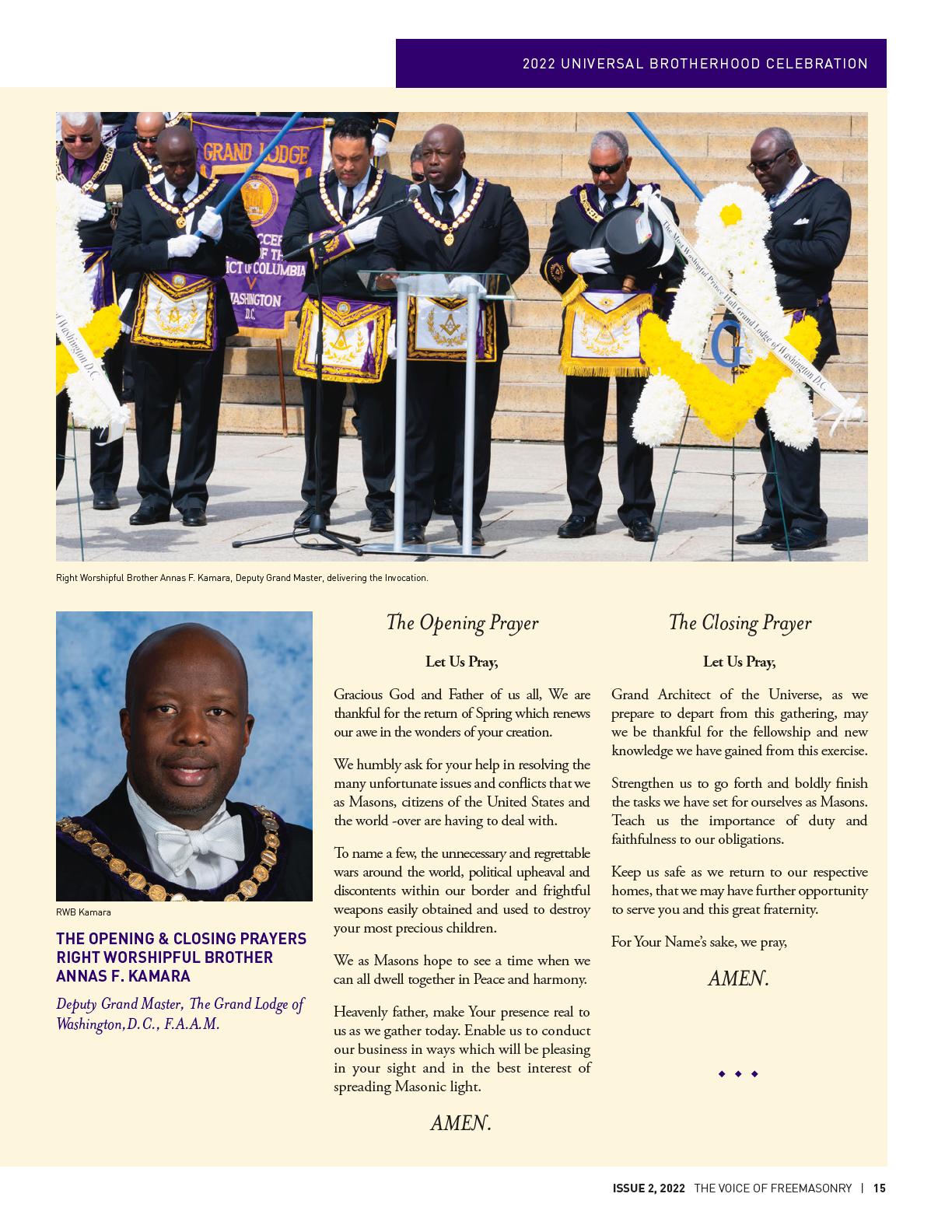

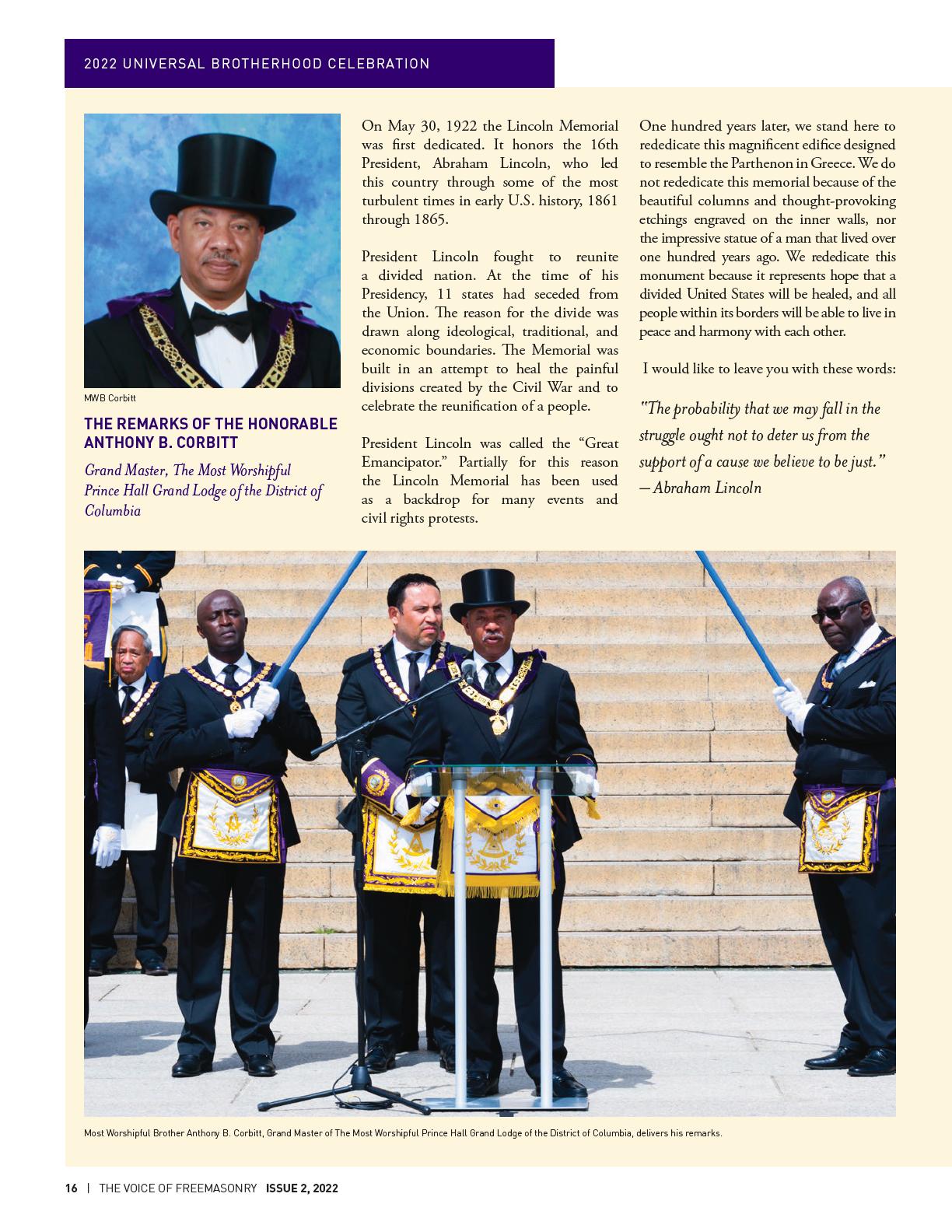

Opening remarks were delivered by Most Worshipful Brother Akram R. Elias, PGM, which were preceded by the Invocation, as delivered by Right Worshipful Brother Annas F. Kamara, Deputy Grand Master. Masonic Wreaths were presented before the Statue of Abraham Lincoln by the Grand Master of Masons of the District of Columbia, and by the Grand Master of the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of the District of Columbia, on behalf of their respective Grand Lodges. Following the presentation of wreaths, both Grand Masters delivered their remarks.

In addition to elected and appointed Grand Lodge Officers of both of Washington, widow, Anne Fairfax, and their young daughter, Sarah. All this occurred while he remained obliged to look after his mother, Mary, and his younger siblings living in Fredericksburg.

D.C.’s Grand Lodges, and members of the Appendant Bodies and Constituent Lodges each respective Grand Lodge, this historic event was attended by several visiting Brethren and distinguished guests, to include, Most Worshipful Brother Richard Maggio, Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts and Honorary Past Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Washington, D.C., F.A.A.M., Most Worshipful Brother Jeffrey Haass, Jr., Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Delaware, Right Worshipful Brother Stephen Tucker, Deputy Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Delaware, and Right Worshipful Brother Andre Faria, Jr., Senior Grand Warden of the Grand Lodge of Rhode Island, among others.

The event was expertly orchestrated and choreographed and was witnessed by numerous members of the general public.

During that summer, a dozen or so men in Fredericksburg organized a Masonic lodge. Many of these men were tobacco merchants who had joined the Craft in Scotland. But there were Freemasons in the area from other places with other trades—including soldiers. If Washington had met Freemasons on Barbados, it is reasonable that upon hearing of the lodge, he sought admission.7

. . . George Washington joined Freemasonry in the Lodge at Fredericksburg, Virinia, through three progressive ceremonies, or degrees. He was initiated an Entered Apprentice on November 4, 1752. Four months later, on March 3, 1753, he was passed to the second degree of Fellow Craft. On August 4, 1753, he was raised to the third degree of Master Mason. He remained a member of this lodge for the rest of his life . . . 8

. . . Freemasonry’s initiation ceremonies, along with its so-called secret grips and words, have appeared in print since the 1720s, but the exact version of the ceremonies Washington received is unknown, as the Lodge’s minutes include no descriptions.9 The printed version that probably comes closest to the ceremonies Washington received appeared in the 1760 exposé Three Distinct Knocks. Although published in London eight years after Washington’s initiation, the seventytwo-page pamphlet scripts the Masonic rituals most common in Irish and English “Ancient” lodges as well as in many Scottish lodges in the 1750s.10

The lodge opened with Washington (the candidate) outside in a waiting room. There, he was divested of his worldly possessions and blindfolded (or hoodwinked). His conductor led him to the lodge door where he was required to make three distinct knocks. The door opened, and a lodge officer asked several questions that either Washington, or his conductor, answered. With the permission of the Master, he was received into the lodge room. A prayer was given and his conductor then led him around the room, so all present could identify him and affirm he was properly prepared for initiation. He was then taken to the lodge’s altar and caused to kneel. With his hands touching a Bible, Washington took upon himself an obligation recited to him by the Master. The obligation was essentially a promise to keep Freemasonry’s secrets and uphold its constitutions.11

The obligation complete, the hoodwink was removed as the brothers gave a surprising clap. The Master then greeted Washington as a Masonic brother and presented to him a white lambskin apron. Then and now, the apron is the badge of a Freemason and must be worn when in a lodge meeting. He was also taught the grip and word of an Entered Apprentice.

According to Three Distinct Knocks, Washington was then likely shown a group of hand-drawn images from the Bible and of stonemasons’ tools, probably drawn in chalk on the floor, but possibly painted on a wood panel. This instructional chart, or “tracing board,” would guide Washington as the lodge lecturer explained the symbolic meaning of his initiation. The lecture also explained the importance of the five senses of human reason and the seven liberal arts and sciences—especially geometry. Once the lecture finished, Washington was reconducted to the anteroom where he recovered his worldly possessions. . .

. . . It remains unknown what Washington thought of the three degrees he received, or if they made any lasting impact upon him. The months between his initiation in November 1752 and his attendance at the first meeting after he was raised to Master Mason in September 1753 were a pivotal time. In December 1752, he came into sole possession of Mount Vernon when his sister-in-law and niece moved to the Fairfax estate. In February 1753 he passed his twenty-first birthday and was appointed the Virginia Adjutant General for the Southern District with a rank of major.12

In November 1753, Virginia Governor Robert Dinwiddie appointed Washington to carry a message to the French forces in western Pennsylvania. A great adventure was before him. In the fourteen months that followed, Washington gained honor leading expeditions to western Pennsylvania, but also suffered defeat at Fort Necessity, before he reappeared in Fredericksburg Lodge on January 4, 1755. His childhood was then far behind him and before him was a promising future of active military service. Like so many other men, Washington’s Masonic initiation marked one of the last passages from boundless youth into dutiful manhood.

This excerpt was orginially published in The George Washington Masonic National Memorial Association “Light” 27:1, 5-6

Works Cited

1 Richard A. Rutyna and Peter C. Stewart The History of Freemasonry in Virginia (University Press of America 1998), 32-34.

2 Johnson, Beginnings of Freemasonry, 117. Kent L. Walgren, Freemasonry, Anti-Masonry and Illuminism in the United States: 1734-1850: A Bibliography. 2 vols. (Worcester, MA: American Antiquarian Society, 2003) v.1, 5.

3 There is no evidence Lawrence Washington was a Freemasons, but he may have meet Freemasons during his education in England in the early 1730s or during his military service in the 1740s. He named his estate Mount Vernon after Admiral Edward Vernon (1684–1757). Adm. Vernon’s father, James (1646–1727) was secretary of state under William III and an important English Freemason. James Vernon was instrumental in the creation of the colony of Georgia. See Ric Berman Loyalist and Malcontents: Freemasonry in South Carolina and Georgia (UK: Old Stable Press, 2018), 112.

4 There is no evidence of members of the Virginia Fairfax family were Freemasons. There were Freemasons among a collateral Fairfax family, in York, England, descended from Sir William Fairfax (1609–1644). Thomas Bowman Whytehead “The Grand Lodge at York” Ars Quatuor Coronatorum, II, 110-114. See also David Harrison The York Grand Lodge (UK: Arima Book, 2014)

5 Jack D. Warren, Jr., “The Significance of George Washington’s Journey to Barbados,” Journal of the Barbados Museum and Historical Society 47 (2001): 6. 41. Alicia K. Anderson & Lynn A. Price, eds., George Washington’s Barbados Diary, 1751-1752. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2018).

6 John Lane, Masonic Records, 1717-1894; Being List of All the Lodges at Home and Abroad Warranted by four Grand Lodges . . . . (London: E. Letchworth, 1895), 86, 95, 97. https://www.dhi. ac.uk/lane/howtoread.php

7 Ronald Heaton & James R. Case, The Lodge at Fredericksburgh: A Digest of the Early Records. (Bloomington IL: Pantagraph Publishing, 1975), 1-4. Walker, J. Travis. A History of Fredericksburg Lodge No. 4, A.F. & A.M., 1752-2002, (Fredericksburg VA: Sheridan Books Inc., 2002), 1-3.

8 Proceedings if the Grand Annual Communications of the Grand Lodge of Virginia, Begun and Held in the Masons’ Hall, in the City of Richmond, on Monday the Eight Day of December, A.L. 5800A.D 1800. Richmond: Brother John Dixon, 1800. 34.Necrology of departed brothers 1799-1800 lists him as a brother of Fredericksburg Lodge no.4.

9 Samuel Prichard. Masonry Dissected (London, J. Wilford, 1730). The first American edition of which was published in Rhode Island ca. 1749, see Walgren, Bibliography, v.1, 6. Exposures of the Masonic rituals appear in London newspapers in the mid-1720s. See S. Brent Morris, “The Post Boy Sham Exposure of 1723” Heredom: The Journal of the Scottish Rite Research Society, v.7, 1998, 9-38 and Douglas Knoop, G.P. Hamer, and Douglas Jones. Harry Carr, ed. The Early Masonic Catechisms. 2nd Ed. (London: Quatuor Coronati Lodge, No. 2076, 1975). Regardless of what exact words and actions were taken, the quantity and consistency among the exposures provide sufficient evidence to reconstruct and strong representation of what Washington witnessed in the Lodge at Frederickburg.

10 Harry Carr, Three Distinct Knocks and Jachin and Boaz 1760 and 1762. Reprint (2 vols. in 1). (Bloomington, IL: The Masonic Book Club, 1981) 70. The book’s title alludes to the way all men gain admission to a lodge; first by seeking a Freemason, then by asking a member to sponsor, or vouch for him, and finally, by knocking on the lodge door and refers to Matthew 7:7. Carr wrote: “That Freemasons widely condemned this exposé reveals how close it was to the actual ‘secret” work.”

11 Heaton & Case, The Lodge at Fredericksburgh, 58-59.

12 Freeman, Young Washington, 266-273. Peter Stark, Young Washington: How Wilderness and War Forged America’s Founding Father (NY: Harper Collins, 2018), 32-34, 181-182.

UPCOMING EVENTS:

Grand Visitations

(all held at the George Washington National Masonic Memorial):

• September 23, 2022

Lodges – 4, 11, 21, 35, 76, 98, 1717, 1821, 3000

• September 30, 2022

Lodges – 6, 14, 32, 47, 94, 925, 1002, 1003, 1776, 2000

• October 14, 2022

Lodges – 5, 10, 19, 34, 25, 90, 222, 1001, 1775, 1893

• August 27-28

Grand Lodge Leadership Conference – at The Bolger Center

• September 17

Grand Lodge Picnic

• October 28th

Masquerade Ball

• November 12 Masonic Day of Thanksgiving

• November 19

The Annual Communication of Grand Lodge – 10:00 a.m. at Almas Shrine Center