6 minute read

ARTS

© Sam Gilliam / ADAGP, Paris 2022. Photo © Fondation Louis Vuitton / Marc Domage.

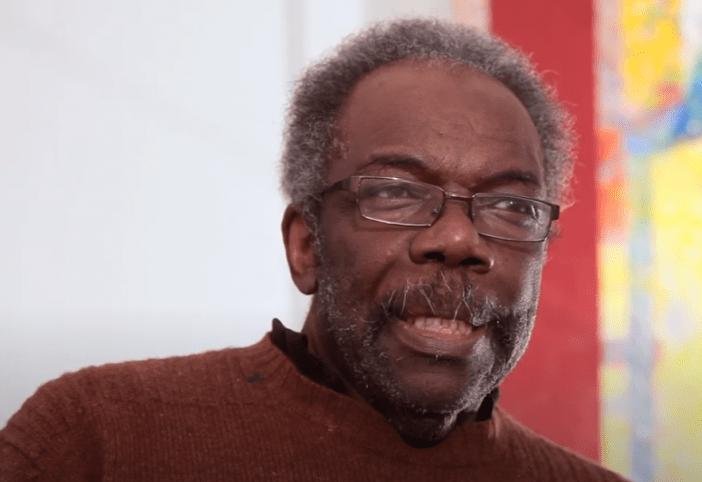

Sam Gilliam, D.C. Artist of Worldwide Acclaim

BY RICHARD SELDEN

Sam Gilliam, among the most important artists ever to commit to living and working in the nation’s capital — which he did for 60 years — died of kidney failure at his Washington, D.C., home on June 25. He was 88.

The last living representative of the Washington Color School movement that put the District of Columbia on the contemporary art map in the 1950s and 1960s, Gilliam achieved worldwide acclaim as an independent and, into his 80s, undiminished creative force.

Gilliam was also beloved in the District for decades of inspiring and mentoring young people, beginning with five years of teaching at McKinley Technical High School and participation in the workshops that preceded the launch of Duke Ellington School of the Arts.

Born on Nov. 30, 1933, in Tupelo, Mississippi, he was the second-youngest of eight children in a family that later moved to Louisville, Kentucky. His seamstress mother encouraged his early fascination with drawing; horses were a favorite subject. Reports vary as to his father’s occupation — farmer (New York Times)? railroad worker (Artnews and NPR)? truck driver (Guardian)? carpenter (Washington Post)? — but he likely inherited a certain manual aptitude from Sam Sr.

Gilliam reached adulthood during the early years of integration. After attending Louisville’s segregated Central High School, he became a member of the second admitted class of Black undergraduates at the University of Louisville, graduating in 1955. Before returning to get a Master of Fine Arts degree, he spent two years stationed in Japan as a U.S. Army clerk. In 1962, just married to Dorothy Butler, The Washington Post’s first Black female reporter, he settled in D.C.

Sam and Dorothy Butler Gilliam were divorced in the 1980s. In 2018, he married his longtime partner Annie Gawlak, director of the former G Fine Art at 1515 14th St. NW, who survives him, as do three daughters from his first marriage.

Referencing jazz in connection with Black visual art has become a cliché. In the case of Gilliam, who in his teens and twenties experienced the music’s transition from bebop to free jazz, the parallel is key to his artistic path. He was just seven years younger than Miles Davis and John Coltrane and three years younger than Ornette Coleman.

Coltrane was a particular influence. Interviewed in 1984 for the Archives of American Art by Kenneth Young, his University of Louisville classmate (and the Smithsonian’s first Black exhibition designer), Gilliam said: “We used to talk about Coltrane — that Coltrane worked at the whole sheet, he didn’t bother to stop at bars and notes and clefs and various things, he just played the whole sheet at once.”

Playing the whole sheet at once — staining, marking up and layering paint on large sections of unframed canvas that he folded, then draped — was what made Gilliam famous. These breathtaking “drape” paintings, semiimprovised color abstractions, perform on the tightrope between painting and sculpture, interacting with the spaces they occupy and taking a different form with each installation.

“Baroque Cascade,” 75 feet long undraped, was a sensation at the 1972 Venice Biennale, where Gilliam was the first Black artist to represent the U.S. The group show — also featuring, among others, Diane Arbus and Richard Estes — was curated by Walter Hopps in his last year as director of the Corcoran Gallery of Art. Sam Gilliam, 1933-2022.

Having begun to make frameless works in the 1960s — inspired by the mostly older Color School painters connected with the Washington Gallery of Modern Art, a cultural landmark of 1960s Dupont Circle — Gilliam explored this signature genre throughout his long career. Supported by sawhorses, attached to walls like oversized bunting, cascading from ceilings, examples are now found in many museums and public spaces. Invited back to Venice 45 years later, Gilliam created a draped piece, “Yves Klein Blue,” that brightened the entrance to the 2017 Biennale.

On that occasion, Gilliam spoke to Artforum about the first outdoor installation, by hook-andladder truck, of a draped work, “Seahorses,” in 1975. Three huge canvas loops, dominated by reds, oranges and yellows, festooned a sheer stone sidewall of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. When a storm blew in, Gilliam recalled: “There was this really beautiful moment when the strong winds inhabited the piece — rays of light shot through the fabric, creating shadows in the folds.”

VISIT GEORGETOWNER.COM FOR THE FULL ARTICLE.

True North: Honest Stories of Finding Home

BY KATE OCZYPOK

Do you feel that you belong? Have you found that place to live where you feel truly at home? When documentary filmmaker Suzie Galler and her husband moved to North Beach, Maryland, they found a house on the water. What Galler called “a real fixer-upper,” the cottage had been sitting for a few years, but she called it a little gem.

The duo were 40 minutes south of Annapolis and completely fell in love with where they moved. The community was welcoming and Galler felt “whole and center” in the small town of less than 3,000 people.

All things converged creatively for Galler. She realized her husband and she found their “true north” in their small Maryland beach town. She got to thinking about friends who found their own true north and sense of belonging. “I know someone who lives in Burlington, Vermont,” Galler said. “She’s a therapist there and has declared she’ll never leave, she’s immersed in the healing community there and loves the people of Burlington.”

There also was another friend who lives in New York City and loves the hustle and bustle of the metropolis and the energy of the urban area.

Galler began to feel inspired and thought there could be a series involving “true norths.” A docuseries, dubbed “True North” was soon born, offering viewers a personal view into the lives of everyday people who take unusual (and many times) brave paths to find their purpose and place in the world.

The pilot episode of the series, called “Sailing to Salvation,” brings viewers into the lives of a group of anguished veterans who have a hard time getting back into society post-war. “They are reclusive, including one in particular, a former sailor who people suggested to get back on the water,” Galler The Valhalla Sailing Project is featured on the pilot episode of True North: Honest Stories of Finding Home.

said. “It made him feel whole and great again.”

The veteran began a program, “The Valhalla Sailing Project,” that helped so many vets find connection and healing by sailing competitively on the Chesapeake Bay. Over 500 veterans have gone through The Valhalla Sailing Project.

True North is “about people realizing they are satisfied and fulfilled, that they have found a sense of community and belonging at an intersection of three things — people, place and purpose,” Galler added.

The docuseries seems to really have hit a nerve with people, motivating Galler to continue to seek out other episodes and broaden past the Annapolis area. According to Galler, True North came in second place for audience favorite at the Annapolis Film Festival.

More information on True North and Suzie Galler can be found here: https://www. studiotruenorth.com/.