7 minute read

CREATIVITY THROUGH DESIGN & MANUAL ARTS

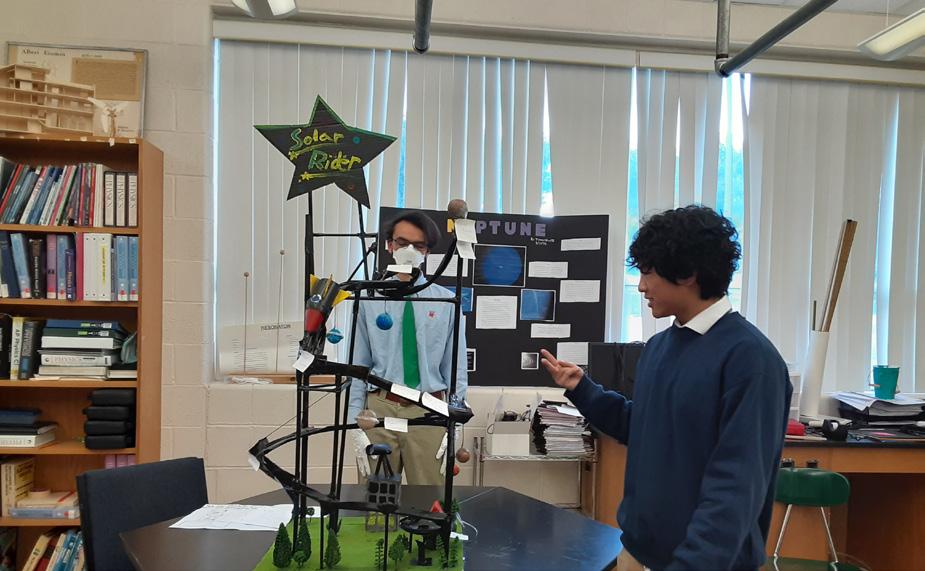

THE INNOVATION LAB CONNECTS STUDENTS TO CAMPUS-WIDE PROJECTS.

By Brandon Neblett UPPER SCHOOL HEAD

On display in Glenelg Country School’s Innovation Lab, home of the Upper School’s digital electronics elective, sits a Flying V-style guitar. Designed by Andrew Roth ’23, the guitar occupies a place of honor and is among the first to catch a visitor’s eye in the dedicated STEAM space.

Located opposite the fitness room, the Innovation Lab is the hub of tools and materials used by students for design and construction. Roth and dozens of students have built these guitars, designed buildings, coded software, constructed furniture, and animated characters by applying the same design process over the past five years.

The guitar project is, in some ways, the perfect school project: it implements fundamental skills in a multi-disciplinary setting with a tangible outcome in which the students are deeply vested. After all, what teenager wouldn’t love to build a guitar? Combining wood, metal, circuits, strings, and basic hardware, the guitars bring learning to life. But, as Roth notes, the sustained attention to detail, precise measurements, and manual dexterity required to build a successful guitar don’t come quickly.

“One challenge I faced while stringing the guitar was drilling the holes for the tuning pegs,” Roth notes in a digital presentation of his project. “They had to be drilled so that the strings didn’t overlap, and they were in line with the notches on the nut. If the hole was too far off by the slightest measurement, playing it was problematic. And we had to be careful when using the drill press because going too fast could crack the head of the guitar. One mistake could ruin the whole thing.”

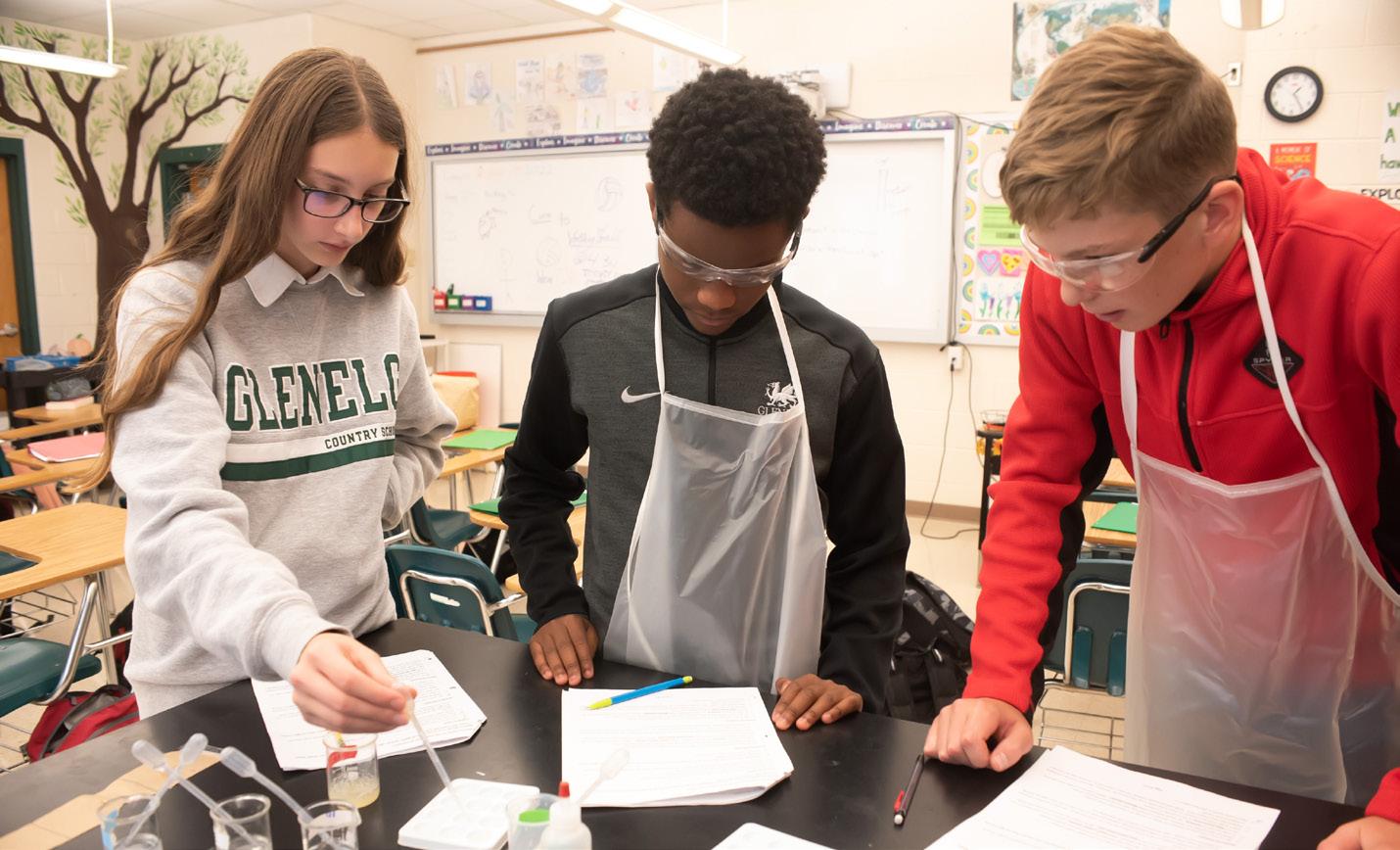

While the Innovation Lab heralds advanced technology, such as the 3D printer and computerized numeric control (CNC) machine, Marc Schmidt, Roth’s teacher, is passionate about the importance of developing a facility with essential tools and materials, the kind you find in your garage or at the local hardware store.

“So many students considering studying engineering in college lack basic skills with hand tools and knowledge of materials needed,” Schmidt says. “Here, we first give students experience in fundamental skills with fundamental tools, whether they want to be engineers or not. They may learn the intricacies of the 3D printer later, but first, they learn to screw, hammer, cut, and solder. These are key skills you need at every level: how to plan, make accurate measurements, pay attention to detail, and develop a sense of craftsmanship.”

Schmidt also serves as the school’s director of academic technology and computer science department chair, giving him access to and interest in resources and opportunities across campus. He brings those directly to his classes and sometimes takes his classes directly to them. He recently invited LaRon Land, an instrumental music teacher, to class to help students tune their guitars and understand the relationship between frequency, notes, and chords. Land even taught students to play a traditional blues progression. Schmidt also asked Scott Proffitt, director of studies and Latin teacher, to share his love of playing guitar and the lessons he learned about vacuum tubes and circuits when he built his 1952 guitar amplifier from scratch.

The Innovation Lab has also sparked collaborations across campus. In coordination with Katie Burkman, a Middle School English teacher, and Melissa Kistler, a Middle School learning specialist, the Innovation Lab team is helping the Middle School’s Destination Imagination program with robotics and engineering challenges. Burkman and Scott Doughty, Middle School Latin teacher, have coordinated with Schmidt and Ben Shovlin to develop block-based coding and Python curriculum for sixth and seventh-grade students.

Shovlin, the lab’s technical director, arranged for Alex Pereira ’23, one of three GCS seniors who have worked in a unique high school internship over the past year at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, to visit the Middle School to demonstrate the robotic arm he is developing.

In demonstrating the transferability of knowledge across disciplines and the interests and expertise of teachers beyond the specific subjects they teach, Schmidt sees the guitar-building project and similar student-centered construction projects as a crucial step for Upper School students thirsty for hands-on, practical learning. But the impact of this work, and other work in the Innovation Lab, extends well beyond GCS.

The Innovation Lab team’s most recent initiative has been building a formal network of alums and parents working in STEAM fields to provide additional resources to students. Schmidt organized an Innovation Lab open house this fall to connect students, alumni, and parents and to provide an opportunity for anyone in the school community to see what happens there. Schmidt reflects, “We are trying to create a culture of collaboration and interdivisional cooperation. It’s all about making connections. And that continues beyond graduation. The GCS community has an impressive track record of success in STEAM fields. We are trying to highlight and celebrate that while providing opportunities to students after they leave GCS.”

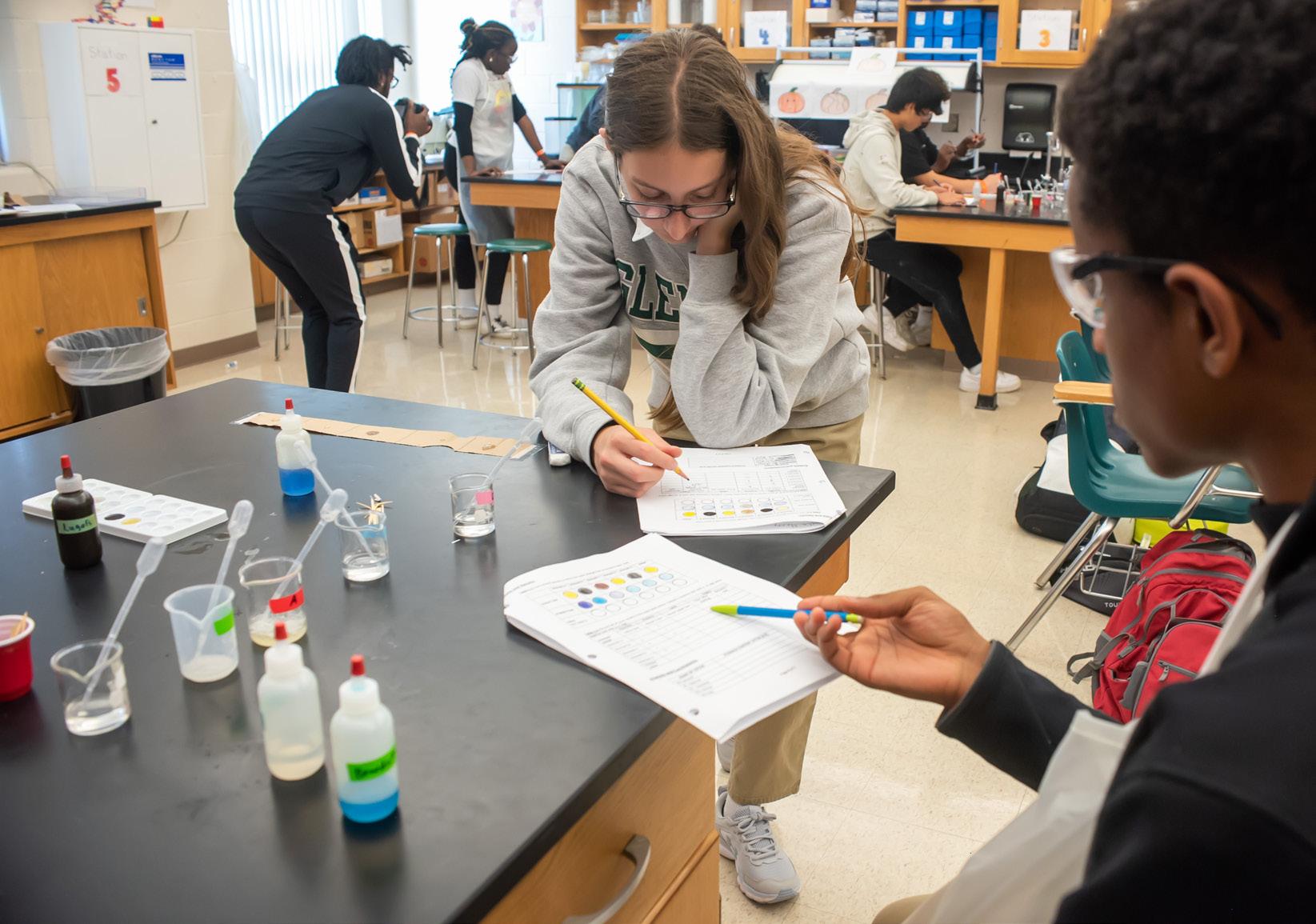

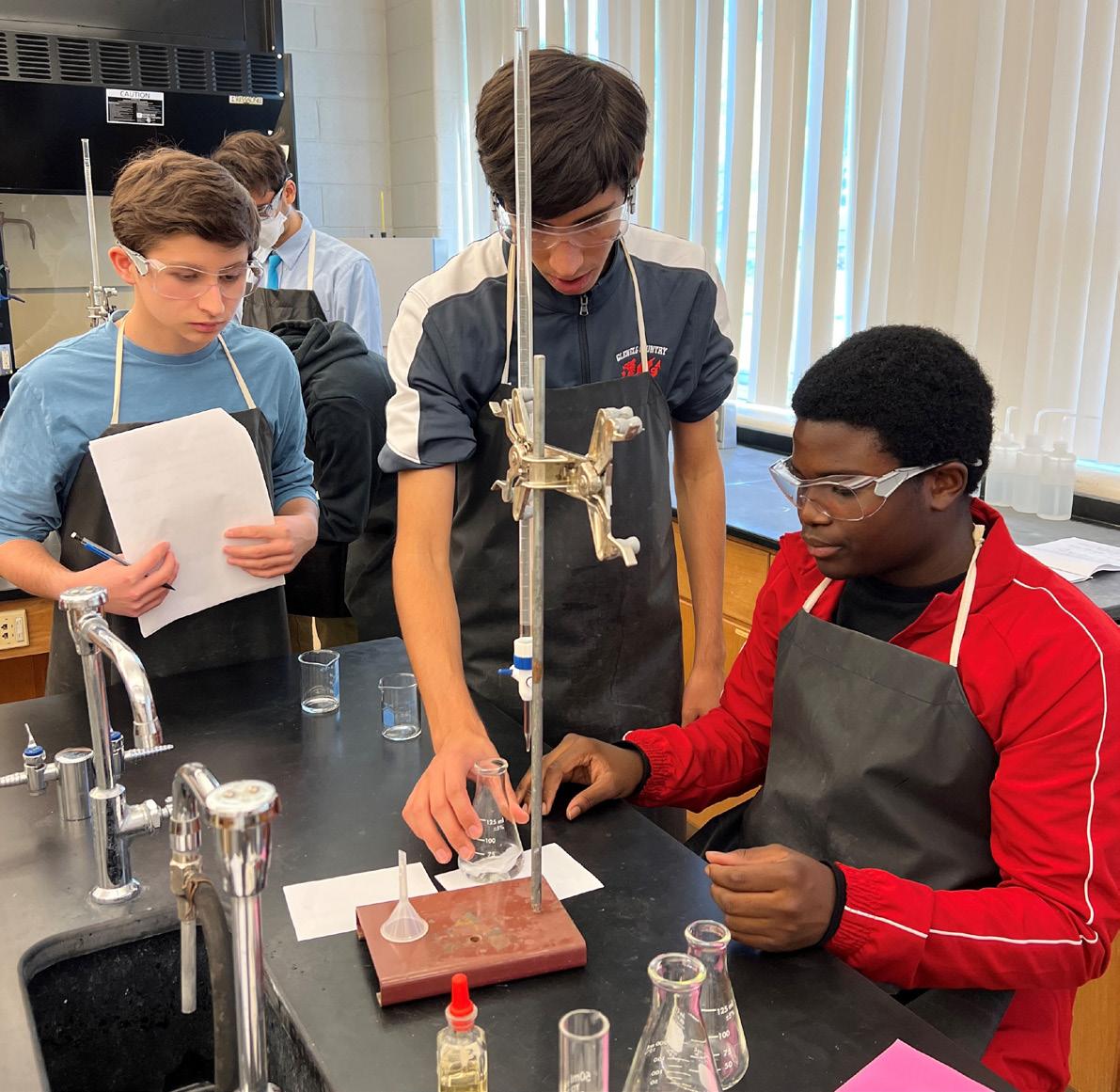

Thinking beyond traditional parameters is also a hallmark of Shovlin, Schmidt’s Innovation Lab colleague. His civil engineering and architecture (CEA) class exposes students to traditional and innovative building approaches and provides opportunities to use tools professionals use. Last year, the class searched for a project to put their skills to use while also making a direct contribution to the GCS community. When the pandemic accentuated the need for outdoor learning spaces, students realized that the Lower School required far more outdoor seating than was available. Out of this realization was born a plan to construct 10 new benches for students, designed specifically for them and sturdy enough to endure all kinds of weather.

“The ownership and sense of agency in the Lower and Upper Schools students made all the difference,” notes

Shovlin. The project focused on making a direct contribution to the GCS community, one that everyone understood. After speaking with Lower School students and soliciting suggestions for the values that would decorate each bench, Upper School students saw how excited their younger peers were about the project. There was no turning back.

But the endeavor required significant effort before actual machine work. This research and development included many meetings and additional presentations. The students consulted with the Development Office and Operations team, faculty, and Hilary McCarthy, head of Lower School, to ensure they had gathered everything they needed before designing the benches. Connecting with all the stakeholders involved in a tangible addition to the campus underscored a sense of responsibility for getting it right. It also included mathematical work such as establishing the exact specifications for the height of the tabletop and seat, which required investigation into how high off the ground) Lower School students completed their academic work.

Having completed all these steps, CEA students turned their attention to developing sketches by hand and computeraided design software. Another round of consultation with stakeholders ensued to ensure that all was ready to produce the prototype, followed by ordering and purchasing materials required for the first build. Then came the cutting, painting, and epoxying “Glenelg Country School” and the values identified by the Lower School students, such as “truth,” “mindful,” and “brave.” This process alone took 90 minutes per word. At five words per table for 10 tables, the CNC machine was in use for 75 hours.

Oversight and maintenance were Shovlin’s learning curve. It was the first use of the CNC machine at this capacity, and no one in the class, even Shovlin, had ever poured epoxy. “Students saw that I was learning, too,” Shovlin notes. “I was going to make mistakes, and they understood that.” In short, it was an authentic process: a unique product filling an immediate need for outdoor academic purposes. Mistakes were part of that authenticity.

This year’s CEA students are building a second set of 10 tables. Looking back on the first year’s work, Shovlin is reflective. “It has been a ‘soup-to-nuts’ production, developed through an intentional framework, and the students see the tangible results of their designs. The entire process has been a ‘Yes, and…’ experience,” he says, noting one of the essential guidelines for improvisational theater. “And seeing the benches used at this year’s Family Day by students and their families was inspiring. I had this moment where I realized, ‘Now the benches are a part of the landscape.’”

Upper School students are also designing and building in other spaces across campus. In Walter Mattson’s Manual Arts class, they drill, cut, and solder on the Chapman Porch, just a few steps from the Innovation Lab. Mattson, a humanities teacher in his third decade at GCS, is a renaissance man. Mattson pursues his passion for building fine furniture as a master woodworker during the summer and is an amateur beekeeper throughout the year. He is as passionate about homemade honey as he is about Emerson’s poetry.

His class’s signature project is the renovation of an antique mailbox for Lower School students. Lower School teacher Karen Dodge saw potential in the massive piece of furniture several years ago and helped procure it for the school. “It was in very rough condition,” Mattson recalls, “racked out of shape, with a rotted sorting surface and missing pieces. The Lower School asked us if the inaugural class of the manual arts could repair and renovate it.”

Students milled and installed a pair of classical pilasters with fluting, a frieze with dentil molding, and an architrave with custom crown molding. The neo-classical, municipal style of the original complements the whimsy students incorporated into the refurbishment as a tip of the hat to the Lower School students who would use it. “After trying several color combinations, students chose the paints and coated the entire piece, including the interior of about 150 little cubbies. By hand,” Mattson added. They had to engineer and adapt rollers and brushes to complete this intricate work.

The Mulitz Theater is another space focused on studentcentered creativity and construction. Corey Brown, technical theater and facilities director, teaches stagecraft classes and oversees all technical preparations for theater productions, including sets, light, and sound. His students are always busy and demonstrate a wide range of skills. To Brown, it’s all about building a vision and making it come to life. Brown comments, “We bring different worlds to life, bringing the audience into that moment.” Following a long-honored GCS tradition, students design, construct, and finish the physical apparatus that sets each play and musical scene. “We work through the challenges together as a team. It’s about creating a vision together to tell a story,” says Brown.

Roth’s final thoughts on his guitar capture the freedom and autonomy central to all these opportunities to design and build. “My favorite part of the project was being able to choose the shape of my guitar and what kind of finish I wanted. I could customize it to my taste and preferences, wanting it to be perfect. I liked that we could choose how we wanted it to look in the end while going through the same process as everybody else.”