1 minute read

How Gleaner helped untie farmers from binder twine cartels

One of the Society’s early projects — supplying farmers with binder twine — showed the promise as well as the pitfalls of progressive cooperation.

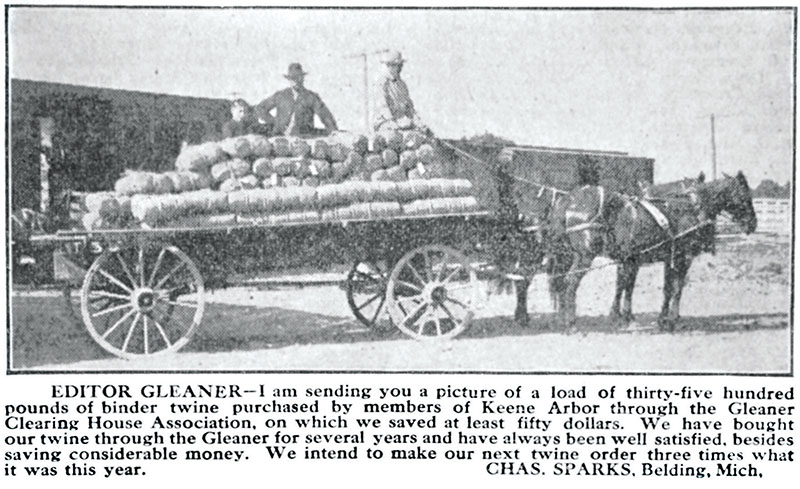

Before modern combine harvesters were developed, binder twine was an essential farm material. The McCormick twine-tying “reaper-binder” for harvesting grain was among several patented in the late-1800s when the Gleaner Society formed. Farmers needed about nine pounds of twine per acre to tie stalks into sheaves when harvesting wheat and other small grains. Michigan alone used 12 million pounds of twine per year. It was no exaggeration when a 1920s International Harvester booklet proclaimed that, “The world’s supply of bread literally ‘hangs by a thread’ — a thread of binder twine.”

Farmers felt tied up, however, by twine costs. Binder twine used in the Midwest usually was made with sisal fibers from a plant grown in the Yucatan area of Mexico. The industry was known to be controlled by a cartel, or “trust,” of both U.S. businesses and Mexican government officials. Suspecting that farmers were victims of price fixing, the Michigan Legislature appointed a committee in 1903 to investigate the issue. One of its visits was to Minnesota’s state prison where a new binder twine factory employed inmates to produce twine at lower costs. Similar prison twine facilities were set up in North Dakota and Illinois. Gleaner founder Grant Slocum wrote in The Gleaner that Michigan should follow.

“Year by year the trust, which now controls nine-tenths of the output of binder twine, has been reaching out its slimy fingers to grasp the sources of raw material, and it is now an acknowledged fact that the supply is pretty well under their control,” Slocum wrote in The Gleaner in January 1907. “Let the prisoners of Jackson state prison make binder twine for the farmers, and bad luck to the hirelings of the Trust who dare to sidetrack the bill which will be presented to the coming Legislature for that purpose.”

Other reasons Slocum listed to support a binder twine facility included giving inmates productive activity and skills, and he noted that Minnesota’s prison industry generated a net profit of $90,000 in 1904 (roughly $3.2 million in 2023 dollars). Critics in the state Senate pointed at the initial cost and wondered whether prison labor should compete with private enterprise. Slocum answered that there was more than enough demand for new suppliers.

In July of 1907, Gleaner farmers helped convince state lawmakers to create a prison factory. “The Michigan State Legislature appropriated $125,000 for a binder twine factory at the Michigan State Prison,” a Gleaner Forum story reported. “On the morning the Bill was placed in the Lower House, opposition raged on all sides and every means was used to prevent passage of the Bill. Had it not been for the united action of 60,000 Gleaner Farmers, who had signed the Gleaner petition asking that prisoners be allowed to make binder twine, the measure would have been smothered in the Committee. Thus, single handed and alone the organized Gleaners won a victory in bringing splendid results to this day.”

Michigan’s prison factory added dozens of machines to turn bales of sisal fiber into finished twine balls, as well as other machines to test samples of twine. Inmates recorded the results and even handled the factory’s accounting. The factory began production in 1909. A February 1910 story described a visit to the operation — including an unsuccessful escape by two inmates found hiding in a railcar full of finished twine.

Michigan Gov. Fred M. Warner was a strong supporter of the project. The venture also was praised by three consecutive prison wardens: Nathan F. Simpson, who stepped down and joined Gleaner leadership in 1918; acting warden Edward Frensdorf; and his successor, Harry L. Hulbert. In an interview with the Gleaner Forum, Hulbert expressed admiration for the Gleaners.

Rivals, however, continued their efforts to shut down the prison factory. Corporations began flooding the Michigan market with cheaper twine costing less than the prison twine. Gleaner responded by agreeing to distribute at cost all the prison’s twine production to farmers who ordered it through Gleaner, ensuring the factory could continue. Gleaner officials noted that, by 1914, the factory was self-supporting. Farmers appreciated the guaranteed supply and prices, especially during World War I when government-imposed price controls limited farmers’ wheat prices to $2 per bushel.

Then, in 1918, the Union Trust Company of Detroit alleged corruption by prison officials, claiming more than $300,000 could not be found in prison factory accounts. It pushed politicians to investigate, and a grand jury was empaneled. The Gleaner Forum speculated the issue involved record-keeping by inexperienced inmates. It disputed the allegations as merely the latest attempt by “big business corporations” to shut down a successful, self-supporting enterprise. “For more than seven years the combinations fought the management of the prison every inch of the road,” a 1919 Gleaner Forum editorial stated. “When they found that the farmers could not be bought off, when they found that they would buy Jackson prison twine regardless of cost, they sought the next plan of destroying the splendid industry, and found the peanut politicians, ready and willing, to join them.” Two months later, Gleaner and all prison officials were cleared of any wrongdoing “and the Detroit Trust Company was given a ‘black eye’ by Judge Benjamin Williams of the circuit court,” the Detroit Free Press reported.

Gleaner continued to sell binder twine to farmers throughout the 1920s and the early 1930s until a variety of changes ended the practice. Congress grew more sensitive to complaints from private businesses as well as concerns about inmate labor conditions in other parts of the nation, especially the South. It passed several federal laws limiting prison labor projects and restricting transportation of their goods across state lines. Perhaps because of this, when Gleaner advertised Jackson prison binder twine for sale in 1931 at a price of 8 ½ cents per pound, it specified the twine was for Michigan farmers. In 1937, according to the Michigan Department of Corrections, Michigan passed a law requiring prison-made goods be available only to state agencies, effectively closing Michigan’s prison binder twine factory. Eventually, farmers purchasing combines replaced most sisal twine binders. Binder twine still plays a role, along with man-made fibers, for baling hay and straw.

Today, state prisons are known for producing government items including license plates. Inmates who work on these projects and learn factory skills are less likely to return to prison after their release, just as the Society pointed out a century ago. Yet Gleaner leaders also discovered issues such as unfair trade, prisoner rehabilitation, foreign imports, political power, and technological change defy easy solutions.

The era when 60,000 Gleaner farmers fought for a binder twine factory at the state prison seems quaint today. Yet its example of Society members working together with government officials to address everyday problems is a memory worth preserving.