10 minute read

GASnews Interview with Davin K. Ebanks

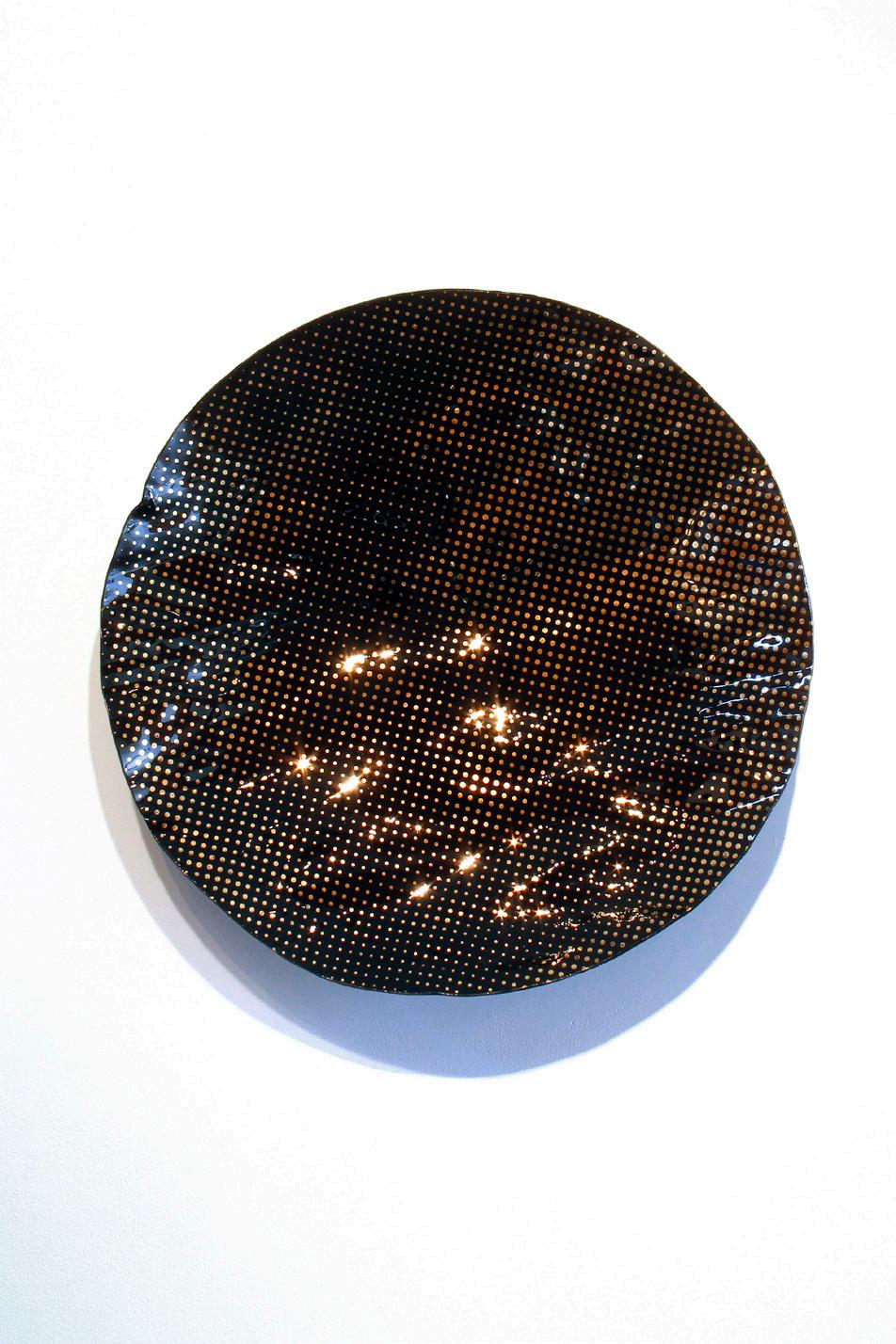

Far Left: Untitled Black (“Some I love who are dead / were watchers of the moon and knew its lore; / …Pierced their ears for gold hoop earrings / as it waxed or waned.”) [Excerpt: Full Moon, Robert Hayden] Kiln-formed (Thermoformed) Glass, Gold / 24H x 24W x 5D, inches / 2021 Photo Credit: Jamie Hahn

Left: Ground Basket Pair (“Drunk with rum / Feasting on a strange cassava / Yielding to new words and a weak palabra…”) [Excerpt: Conversion, Jean Toomer] Blown & Silvered Glass / 10H x 12W x 12D inches each / 2021 Photo Credit: Jamie Hahn

GASnews: Through the many facets of your professional career as an artist, educator, technician, scholar, community member (…etc.) you have to assume quite different roles. Do certain roles take precedence over others?

Davin Ebanks: OK, here’s the deal: if you’re going to be an artist in academia at a research institution, you’re going to have three main duties: Research, Teaching and Service. Depending on the school, they might be specifically in that order. That should mean that I prioritize research, which for artists is just a fancy word for making work. However, the other duties—teaching, maintaining equipment and service, committees, etc.—are all scheduled for you like a normal job (this isn’t counting emails, by the way, which can take up an inordinate amount of your day. My advice is to take a professional workshop on how to manage digital communication before you get into academia…Seriously.) To be clear, I love teaching, and I find studio maintenance and equipment fabrication extremely satisfying. Watching a new glass student fall in love with the material is deeply fulfilling, and working in a smooth-running studio is a thing of joy. That stuff gives you immediate positive feedback.

Making my work is much more emotionally challenging. Even after all these years of knowing how important it is for me to make art, scheduling studio time can still feel selfish, even self-indulgent. Intellectually, I know it’s not—my job literally depends on it—but making art is always difficult, and it’s made even more so by the fact that there’s always something more urgent (but probably not as important) demanding attention.

GN: There is a typical story in our community of discovering glass and being swooned by its muse-like allure. What drew you to the material and how has that transformed through your career? DE: Symmetry. When I was a kid, I would sit and watch my dad throw pottery on an old kick wheel. It was mesmerizing. When I discovered glassblowing in college it was the same feeling. I happened to attend the only school in Indiana that had glass (at that time) and even though I was a Graphic Design major I took every glass class I could. As I got involved with the material, I realized that it was seductive on many levels. There is the sheer spectacle of it—its glow, its physicality, the intensity of the colors—but it can also be fiendishly difficult to make artwork from it. There’s a satisfaction in simply getting it to do what you want. Also, glass does things that other materials can’t do (or cannot do as easily). In the hot shop sculpting or blowing glass, you have this very direct manipulation. Unlike other materials where I would have to create the impression of fluidity or tension, with glass that is part of its essence. That brings me to color.

Like marble or gemstones, cast glass is a color through and through; it’s part of its nature. I work a lot with cast and kiln-formed glass, and it’s a very unique experience as an artist. Unlike other materials where the color is applied to the surface, glass has the quality of simply being that color, and it’s the thickness of the material that shifts the intensity of that color. In a sense, when I use glass I get to sculpt with light and color. So, for all those reasons I continue to make my work in glass, but also, after years of working with the material, I simply use it because it’s what I know. GN: How has your background and personal experience influenced your current body of work?

DE: My work is about space, place and self (identity), and their interconnectedness. I use my personal and cultural history as inspiration. I was born and raised in the Cayman Islands, so for me and many of my people the water surrounding us was as much a part of our daily lives as the land on which we lived. My ancestors were sailors, turtle-fishermen and shark-hunters. I practically grew up on the water fishing with my grandfather, so water is a major influence in my work.

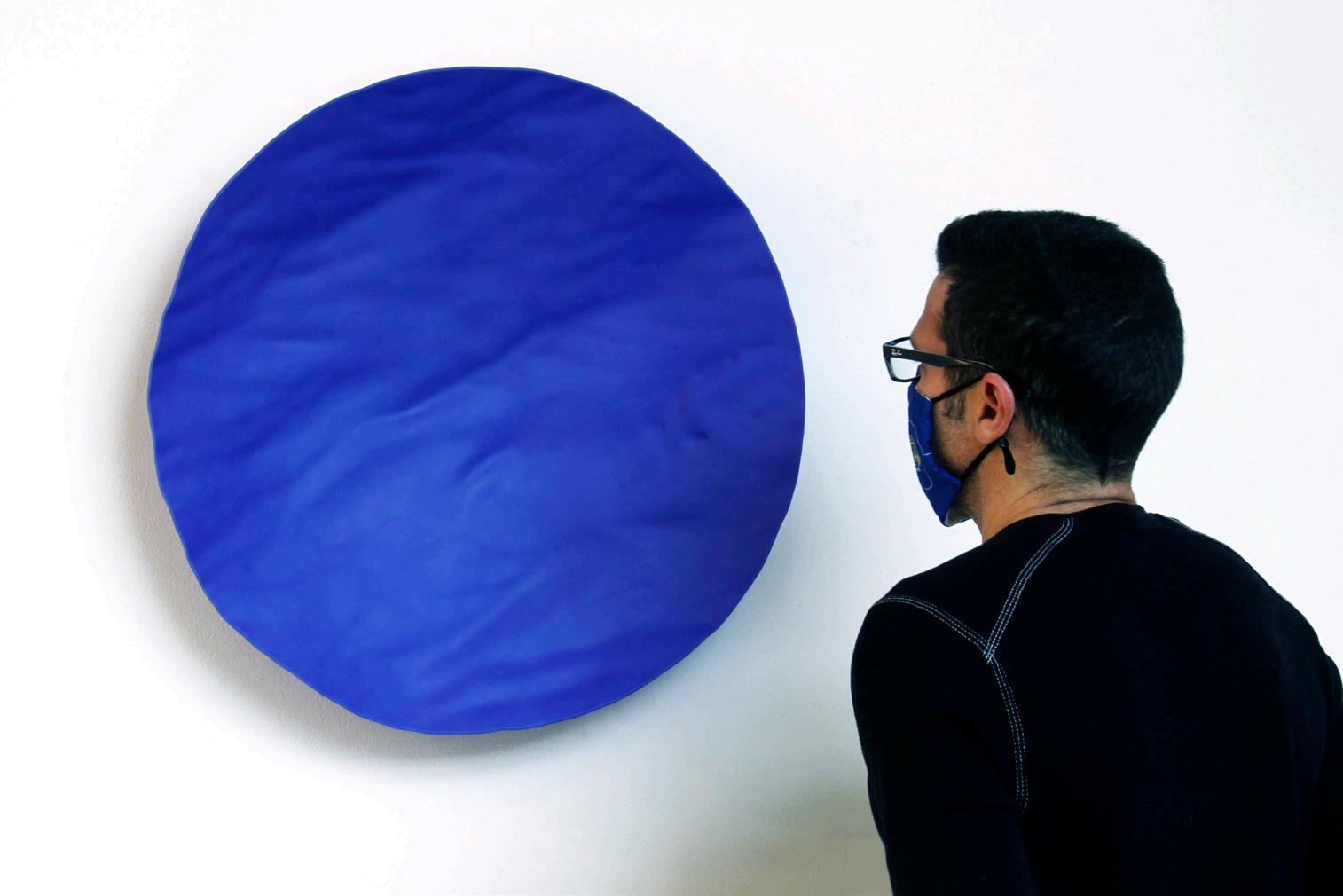

The color blue has been important to my work for a while, but specifically as representative of water from the coastline of Grand Cayman. For my recent work, I pointedly researched the metaphorical and historical relevance and mythology of blue. Although still referential, the pieces are more suggestive of open space (water and sky) or as the liminal space where they meet. This is the blue seen through the open window or porthole: everywhere, yet nowhere.

I also grew up with wild cotton growing in the empty lots behind our yard; there’s only one reason that cotton was there and only one group of people who farmed it. As a Caymanian-American my racial identity is linked to Black people who didn’t make it all the way across the Atlantic, a people left stranded in the blue space of the Caribbean. As such I see my work as being firmly mid-Atlantic, with all that that implies.

Untitled Blue (“Do not drown me now: / I see the island / still ahead somehow”) [Excerpt: Island, Langston Hughes] Kiln-formed (Thermoformed) Glass / 24H x 24W x 5D, inches / 2020. Photo Credit: Jamie Hahn GN: There is a solemnity to this recent work, with the forms, objects, and material appearing as ghosts and reliquaries. How has the physical and cultural distance from your native home impacted your work and interpretation through a material like glass?

DE: Interestingly, I have been thinking a lot more about what it means to be one of the Caribbean diaspora in these times. Before COVID I felt more connected to my specific island home but less connected to the Caribbean as a whole. There is now a gulf between my life here and that of those back home. Everything is different: they haven’t worn masks in over 6 months, so life feels normal for them, but it’s very difficult to get there and just as difficult to leave, so families have been separated for over a year. I used to visit a lot, usually for a month in summer. Cayman is where I do my research and creative reflection. It’s where I can put the studio—that physical and mental space of making—out of my mind and get “bored” enough to recharge the creative juices.

On the other hand, I feel more connected to a common Caribbean experience—as a member of those island nations that have (in large part) closed their borders, cutting themselves off from critical revenue and limiting essential imports. I can relate even more to Bahamians or Jamaicans or Trinidadians, because through the lens of social media I can see how my life in exile is similar to that of other diaspora and how my family’s life back on my native island is similar to that of other island nations. There seems to be more sharing of what it means to be Caribbean, even when we can’t be in the Caribbean. But the largest impact of the last year has stemmed from the global BLM protests. I simply didn’t feel I could keep making the same work in what felt like a different world. This led to more research into the connection between my Black ancestors in the Caribbean and African-Americans.

This is what I mean by the work being mid-Atlantic: it’s a meditation on voyages and Black bodies within liminal spaces, moving between worlds. This came directly out of rethinking my greater connection to the African diaspora and how the Caribbean experience can possibly add to the conversation.

But, I think there’s more behind the new work than simply having conversations about the Black experience because of the BLM protests. In a way I think the quarantine last year had the same effect on my creative process as my annual trip home. I was forced to take a hiatus from the studio—forced to get bored, read, research, contemplate and eventually push my practice in a new direction. I do miss home, but am also strangely grateful for the forced exile and the conversations it has started.

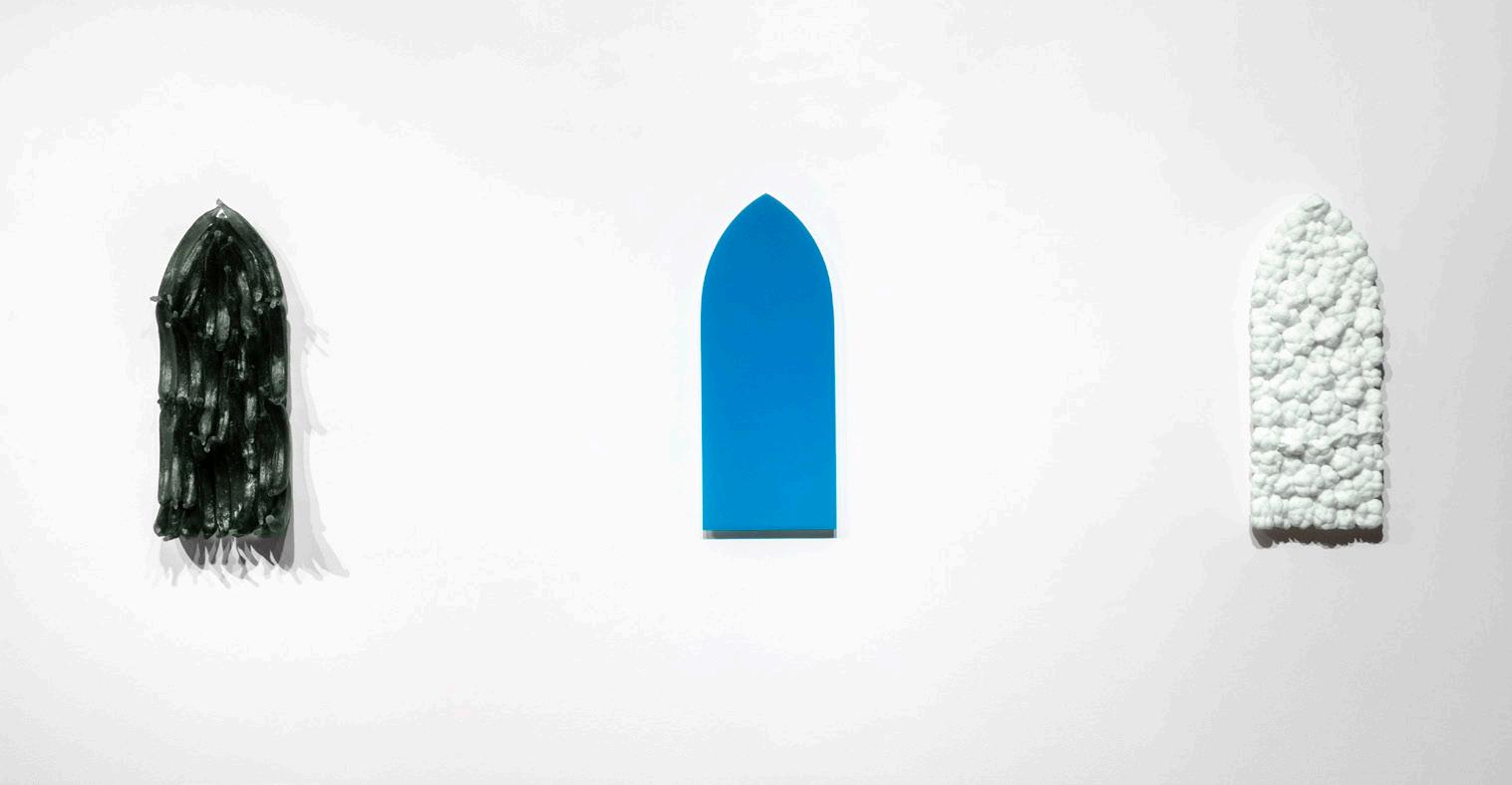

Passage: Negro (“can we find light in the never-ending shade? / The loss we carry, / a sea we must wade.”) [Excerpt: The Hill We Climb, Amanda Gorman] Cast Glass / 24H x 9W x 4D inches / 2021 Photo Credit: Jacob Koestler at The Sculpture Center Passage: Blanco (“Thunder blossoms gorgeously above our heads, / Great, hollow, bell-like flowers / Rumbling in the wind...”) [Excerpt: Storm Ending, Jean Toomer] Cast Glass / 24H x 9W x 4D inches / 2021 Photo Credit: Jamie Hahn

“But occasionally, from out of this matter…” (Portrait of the Artist) Blown, Hot-sculpted & Sand-carved Glass / 14H x 5W x 8D inches / 2019 Photo Credit: Jamie Hahn; Kerry & Betty C. Davis Collection

GN: Are there metaphors drawn from these ancestral and personal histories of processes to sustain (fishing, farming, etc.) and the artistic processes that you adopted after leaving the Cayman Islands that you use to translate experience?

DE: You know, I’ve never thought about that. In fact, until now I haven’t felt as if I’d permanently left home. I’ve always sort of felt vaguely itinerant or migrant: someone who works away from home. I can’t (reasonably) work in glass in Cayman, nor teach at a college level. So, I live in the States where I can pursue my work but then return home whenever I can. The pandemic changed all that and forced me to invest in making my home in the States more permanent.

To the other part of the question, I do think for me there is a parallel between fishing and art making. Both require a kind of willingness to go where the tide leads, to be sensitive to what the signs are telling you. Creativity also relies heavily on happenstance, which can be incredibly confusing and frustrating. Some days the winds are more favorable, the sun is shining and fish are biting; other days the elements are against us but we still get out there and try to make something happen. Art making, like fishing or farming, involves a lot of time where you’re working but nothing much actually seems to be happening. You need patience to see it through. I think this is especially true in glass.

Davin K. Ebanks is a Caymanian-American sculptor who primarily utilizes glass to explore his personal and cultural history and examine the relationship between identity and environment. His work has been published in A-Z of Caribbean Art and his glass sculptures are in the collections of His Royal Highness, Prince Charles, The Kerry & C. Betty Davis Collection of African American Art and The National Gallery of the Cayman Islands, to name a few. He is currently Assistant Professor (Head) of the Glass Program at Kent State University in Kent, Ohio, USA.

Live Two-Hour, Interactive Web Workshops with Renowned Glass Artists Link to Class Recording Never Expires!

Fused Glass Sculptures with Lisa Vogt

Kaleidoscope Pattern Bar Adventure 101 with Susan McGarry August 3

Glass Compatibility & COE,

What Does it Mean? Lecture

with Henry Halem August 5 Miniature Glass Gardens with Dennis Brady New August 10 and 12

Fun with Flowers

with Dennis Brady August 17

Sticks and Stones

with Cathy Claycomb August 26

Fused Glass Lilies

with Dale Keating September 2

Creative Slumping

with Lisa Vogt September 7

Kiln Sculpture

with Dennis Brady September 14

Inside Out Flow Vessel

with Nathan Sandberg September 16

Making and Using Custom-Made Frit

with Tony Glander September 28

Marketing Art a New Way, Lecture with Scott Ouderkirk September 30 MORE Kaleidoscope Pattern Bar Designs with Susan McGarry October 7 Fused Glass Sculptures with Lisa Vogt October 12

Teaching Glass Art, Lecture with Dennis Brady October 21 Glass Weaving with Dennis Brady November 4 Lustrous Lanterns with Lisa Vogt November 9

Visit the Glass Expert Webinars® link under “What’s New” at www.GlassArtMagazine.com for more details and local times.