15 minute read

My Life Outdoors & Doing Our Bit for the Planet

This is a free read from Ghost Dance issue 01. To unlock full access to all content, please purchase the magazine for £8.00 / €9.00 / $11.00.

My Life Outdoors & Doing Our Bit for the Planet

Advertisement

Entering his ninth decade, the business pioneer shows no signs of slowing, and his fight for the planet is as relentless as ever. Here, speaking from his cabin home in Jackson, Wyoming, the charismatic adventurer, environmentalist and founder of Patagonia talks about why we should all get out more and the importance of doing our bit for the planet.

Words by Yvon Chouinard / Interview and transcription by David J Constable

Yvon Chouinard

Photo supplied by Patagonia

I have climbed mountains on all seven continents. That includes Antarctica. If you can get me to the rock, I can still climb it. It was climbing that set me on this path. I saw the damage we were doing to the planet - consumerism, pollution, not recycling. Just travelling with my eyes open, I could see that we are destroying the planet. Patagonia is in a position to do something about it, so that is what we've set out to achieve. So much of who I am and what we have achieved with Patagonia goes back to mountain climbing and early lessons.

I was born in the state of Maine, which is all French-Canadian people, and I couldn't speak English until I was eight years old. Then we moved to California, and I was put into public school. Of course, I couldn't speak any English at first, plus I was the smallest guy in the school, so that meant that I got into a lot of fights, and I ended up running away from school. I learned very early that life is a lot easier if you break the rules instead of conforming. From then on, really, my life was in nature. Before the other kids had even learnt to cross the road, I took my bicycle out for miles, sneaking onto golf courses and going fishing in the lakes.

I thrived in nature and became interested in hawks and falconry. Since I was climbing up cliffs to see these birds, I became interested in mountain climbing, too. When I was sixteen, I drove my car out to Wyoming and started climbing mountains. I turned that passion into making climbing equipment and learnt metalwork and how to become a blacksmith. You know, if I were to describe myself, then I would call myself a craftsman and an entrepreneur. When I look at anything, I think I can make it better than that! I'm not an inventor; I'm an innovator. So, that's what I did with the climbing gear. My company then, Sweetheart Equipment, redesigned every piece of climbing equipment from ice pitons to axes.

Scaling the ridge on the Lagginhorn in the Pennine Alps, Switzerland

Photo by Jef Willemyns

We used the products ourselves and were on the cutting edge of climbing equipment. Every time we used them, we'd come back and discuss how we could make it better. I'm not a businessman, though. Hey, I'm a child of the 60s. We hated politicians, and we hated business people. We were living on the fringe of society. It was very easy to do that then. It was the height of the fossil fuel age. You could buy an automobile for $15 or $20, and gasoline was 10 cents a litre. You could travel and camp for free - we were free people.

Back then, you could get a part-time job anywhere and follow your passion. So, I'd work for six or seven months and then travel around the country for the rest of the year, climbing and making equipment. I wasn't making much money, but I was having fun and following my passion. Then, around 1970, I started making clothing. In 1973, I started Patagonia, making clothing for climbers. It wasn't until ten years later that I finally admitted that I probably was a businessman. I'd never considered myself one, always more of a craftsman who had ideas, but in order to take the company further and do things on our own terms, I had to move forward with that. We decided as a company that we wouldn't be like everybody else; if we invented our own game, then we'd always be a winner. If I tried to be a basketball player, I'd lose. So, we made our own game and our own rules. We started one of America's first on-site child centres at work. We made a commitment to make the best product. Not the most profitable, but the best quality - clothing and equipment.

Surfer catching the last golden rays of the day, Piha, New Zealand

Photo by Bill Fairs

This is for climbing and the outdoors. If it fails, you die. I never studied fashion, but I did take the principles of industrial design, so if you have a problem, then you build something to solve that problem. I applied that to making clothing. So, If we make a bikini, for example, we can't just put it to a model and say that it looks good. We have to think about how it will move, what it needs to do, will it stay on? A bikini is a tool with fabrics that needs to move. The same for a wetsuit or mountain climbing clothing. Clothing is a tool. Our teams know this because they use the clothing, tried and tested, and then discussed how it could be bettered and improved.

I woke up one day and thought about how we're causing so many of the problems with the planet ourselves. So we decided to minimise the damage we're causing but not using industrially-grown cotton and go with organic cotton. We made a commitment to cause the least amount of harm in our business, so that meant using recycled fibres, and we made a pact with our customers that when they outgrow their jacket or it falls apart, we'll fix it, or we'll buy it back from them and re-sell it to someone else - or, we'll take it apart and recycle every part of that jacket. That way, the jacket is owned forever. It is our responsibility to do what we can with a product and give it a new life, rather than just throwing something away.

So, while I never wanted to be a businessman, I learnt that I could use the resources I had (the business) to do some good. Then we started an organisation called 1% for the Planet, which takes 1% of our sales, not our profits, and gives it to thousands of different environmental organisations worldwide. Now this organisation has, hmmm... maybe 3,000 or 5,000 members - I don't know exactly how many. This is philanthropy, and it's the cost of doing business.

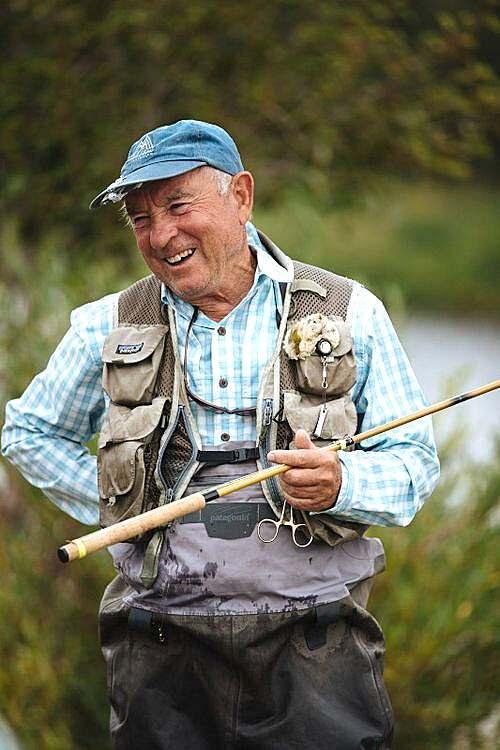

Yvon Chouinard fishes with a tenkara rod, the ultimate in simplicity when it comes to fly fishing

Photo by Jeremy Koreski

A few years ago now, we decided to take all our revenue from Black Friday and give it away to environmental causes. The year before, we had done around $3 million. I don't have any investors or stockholders, so I can do whatever I want. In the afternoon on that day, someone called and said that our sales were up to $6 million. Later that day, $10 million. We only advertised on social media three days before. Woah, that's a lot of money. Surely our sales would die after Black Friday, I thought. I discovered that 60% of the sales were from new customers, people who had never bought from Patagonia before. A 30-second ad on the Superbowl would have cost us $5 million, and we would never have received the customers we did that day. Sales followed right through, past Christmas, and they've continued ever since. Doing the right thing makes you more money. No for everyone, but for us, it did.

When we started, people weren't aware of the impact human beings were having on the planet. They didn't realise that when you buy a pair of no-iron paints, they're that way because toxic chemicals are used with the cotton to make them that way. We had to educate ourselves and then our customers, and they slowly came around. But you know, we didn't care if we lost business or not. It was a matter of doing the right thing. In the end, I found that every time we made a decision that was better for the planet, we actually made more money - how about that! We looked beyond the production of clothing towards other methods. We changed our mission statement, focusing on saving our home planet. So what does that mean for us? Well, we actually needed to live that mission statement? We came up with four ways that we could help save the planet.

Yvon fishing in Snake River, Wyoming, United States

Photo by Sam Beebe

Number one was to use organic cotton because it does less harm than industrial cotton and wool. Beyond that, it must be regenerative, meaning that it's cotton that's grown in a way that builds soil. The United Nations tells us that we have 40 full harvests left in the world. That's 40 years left of topsoil and even fewer years for water. Using regenerative organic, you actually build the topsoil by hand, done on a small scale and therefore employing farmers. We started in India with 150 farmers who grew regenerative cotton. The next year, we had 650 farmers. Now we have over 1,000. The first product from this came out last year, and they're the shorts that my daughter put the label in, reading 'Vote the a**holes out!' They were a big success and sold out in two weeks, of course.

Secondly, we got rid of the evil government we had. Thirdly, we have to support organisations that are helping to educate third-world women and countries because an educated woman will choose to have fewer children. And fourthly, we have to save large wild areas of what's left on the planet. These areas capture carbon and make oxygen. They're the four parts of our mission statement that we're working on. But, you know, food is actually my big interest right now. We're going to need 50% more food by 2050. That's only 30 years from now. And we're not going to have any topsoil or water. So what are we going to do? Answering that question is a big interest of mine.

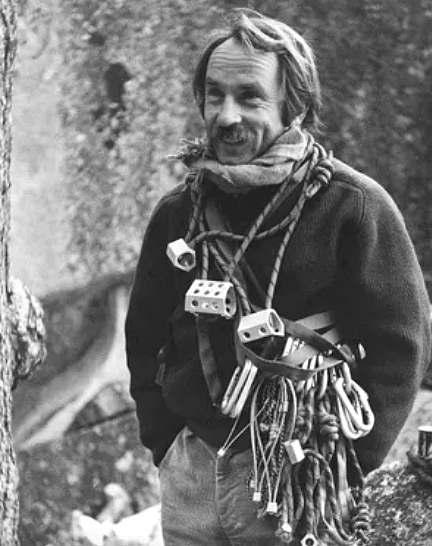

Chouinard with early rock climbing equipment

Photo supplied by Patagonia

I've always been interested in food, learning how to cook from my parents. Patagonia has now started Patagonia Provisions. Our goals are the same as with everything we do - we aim to make the best product, cause no unnecessary harm, and, most importantly, inspire solutions to the environmental crisis. There are about 120 products now that are either organically grown, regeneratively grown or are on the way to being certified regeneratively-organically grown. Our marketing story informs and tells people why they should be eating those foods. Every item clearly states on the packaging where the food is sourced from, so the 100% grass-fed buffalo jerky comes from Wild Idea Buffalo in the Midwest. The wild sockeye salmon comes from sustainable salmon runs in the Pacific Northwest.

The number one product right now is actually canned mussels from Spain. We did one million cans of mussels last year! The muscle is the perfect product - it's grown without you feeding it; you just put some rope in water, and they filter-feed. They clean the water, and you can just leave them alone. That's as sustainable as is possible. We're also doing sardines and anchovies, mullet, mackerel and all fish that don't eat other fish; they eat plankton and algae. It's both sustainable and much healthier.

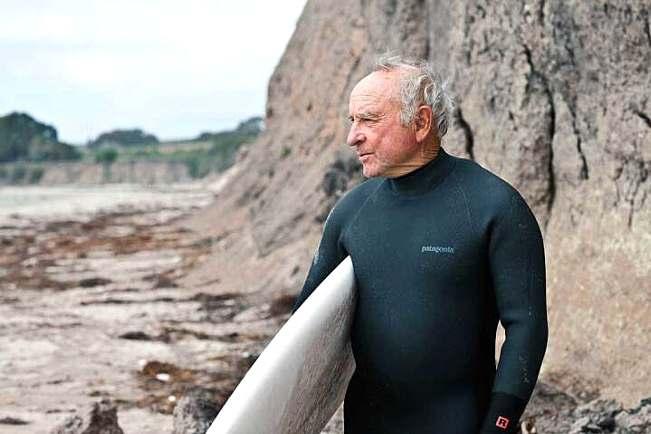

Yvon Chouinard is a keen surfer and even named his 2005 memoir "Let My People Go Surfing: the education of a reluctant businessman"

Photo by Jeff Johnson

A study in the 1930s looked at animals, what they ate, and what they choose to eat when they're sick. When a dog is sick, it goes out and eats grass because it knows that it's the right thing to do. Wild animals know intrinsically what it is they should be eating. Humans have lost that. From a very early age, humans are fed what they are told - sugar and canned baby food - and they become addicts to this stuff. This study in the 1930s was in Canada, and they took some orphan children and fed them milk from a young age and then when they were ready for solid foods, they dressed a table with all kinds of different foods, and then let the children eat. The children knew what they wanted to eat and what they needed to eat. In fact, there was one child who would drink cod liver oil, and they later found out that he had a vitamin deficiency, so he was going for what his body knew that it needed.

In West Virginia, in the Appalachian Mountains, women who are close to nature will eat clay when pregnant. Yeah, clay! They know that they need the minerals from clay. When you lead a life close to nature, you know intrinsically what you should be eating. We've lost that in modern society, and we're eating junk food and not getting the minerals and nutrients our body needs. And now we have all of these modern diseases, like diabetes and other inflammatory diseases.

Buffalo farm, South Dakota, United States

Photo supplied by Patagonia

We own a buffalo farm in South Dakota, and the animals have a choice of eating over 300 different types of plants. And that meat is so much more nutritious than eating beef, where the cow eats nothing but hay all winter long or is in a pasture with only three of four things to eat. Compare that cow with a cow in the Alpine meadow, which has, maybe, 50 different things to eat.

One of my favourite quotes is, you are what you eat, eats. You see, so when you're eating beef that only eats hay, you're eating hay. We've tested our buffalo with other buffalo sent to the feed-lot, and there's no comparison for the nutrients - vitamins, potassium, etc. There's something like 26,000 micro-nutrients. You know why? Because nature made it that way. Nature isn't stupid. This is really important stuff. It's also really exciting stuff! I wish I were a scientist, but I'm not. I'd love to be studying things like this more. Look at the difference in wine; for example, if you try to make wine from table grapes in Califonia - they're Cabernet Sauvignon grapes - it's terrible. They sell the grapes for $800 a tonne, but 200 miles north, the Cabernet Sauvignon grapes make as much as $30,000 a tonne. So, what's the difference? It's the terroir, the weather, the length of the vine; it's how it's grown; a struggling plant will put out more nutrients than one that isn't tested. The vineyards in the Napa Valley put these lie detectors on the plants, like the FBI or something, to tell when it's struggling to grow. Struggling is good, but not too much.

Here in Wyoming, we pick wild blueberries, but this was a terrible year for them because it has been so wet - plants have egos! Ah, I don't have to produce any blueberries, but I'll put all my energy into my leaves and growing, says the blueberry bush. The opposite behaviour occurs when there's a drought, and the blueberry bush produces tonnes of berries. Oh, I might die, so I want as many children as I can have! You see, the blueberry bush has an ego. It's really amazing when you learn this stuff, and you start to understand the behaviours and what is going on with plants. We all must begin to learn, to teach and educate ourselves, and live more naturally. I see this as a tremendous opportunity.

Patagonia Provisions. People often ask why a clothing company is in the food business. The answer is simple: We are in business to save our home planet. And given that agriculture is responsible for about a quarter of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, how and what we choose to eat presents a huge opportunity for positive change. Plus, we just love great food.

Photo supplied by Patagonia Provisions

Patagonia Provisions. People often ask why a clothing company is in the food business. The answer is simple: We are in business to save our home planet. And given that agriculture is responsible for about a quarter of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, how and what we choose to eat presents a huge opportunity for positive change. Plus, we just love great food.

Photo supplied by Patagonia Provisions

Now, there's Covid, and our health is more important than ever. Surely there's a message there? When I was born, there were 5oo million people on the planet, and now there is close to eight billion. A few years ago, it was concluded that if we carry on consuming at the rate we are, then the earth is sustainable for about 2.5 billion people. Last year, studies showed that that figure is now down to 1.5 billion. So what can I do using my business as a catalyst for change? I'm going to try and sell as few clothes as possible. Yep, I'm going into the rental business. If you ski one week a year, why should you buy an expensive jacket and pants? Why not rent for that one week? That's the way we're looking at things now as a company renting, repairing and recycling. I may have a smaller company five years from now, but I honestly don't care; I never wanted a company anyway!

For over 80 years, Yvon Chouinard has followed this own advice, pursuing, with equal fervour, sports adventures, business excellence and environmental activism. A keen climber, notable ascents include Mount Edith Cavell's North Face, El Capitan's North American Wall (using no fixed ropes) and Cerro Fitzroy's Southwest Ridge, aka California Route. He is the author of half-a-dozen books, including "The Responsible Company: What We've Learned From Patagonia's First 40 Years" and the best-selling "Let My People Go Surfing: The Education of a Reluctant Businessman." In 2018, he was awarded the Sierra Club's top award, the John Muir Award, for Patagonia's awareness and environmental responsibility. Learn more at www.patagonia.com and Patagonia Provisions at www.patagonia.com/why-food/

David J Constable is a writer, editor and CELTA-qualified teacher of English to speakers of other languages. He is also the founder of Ghost Dance. Born in Maidstone, Kent and educated in both the UK and USA, he has led a nomadic life, living in London, Kansas City, Bangkok, Lucca and now Kent on the English coast. Follow him at @davidjconstable