4 minute read

Wearable Medical Technology

By Sam Easter / Special for Prairie Business

Browsing through the website for Minnetronix – the St. Paulbased medical tech designer – is like looking into the future of medicine. There’s a wearable nerve-stimulator that helps stroke survivors fire the muscles in their lower legs. There’s a wearable glucose monitor that’s not much bigger than a few quarters.

But to hear Jim Reed, a Minnetronix executive who works closely with wearable medical tech, talk about this stuff is to sense that the future is already arriving. Reed is a happy evangelist for Minnetronix and for the arriving medical future, which he foresees becoming so much cheaper, and so much more accessible, that it will start shifting the economics of medicine.

Reed offers the case of his own father, who recently died with a vascular condition. The promise of Minnetronix products – and the constellation of emerging new medical tech – is that easy-to-wear products can detect ailments early. That not only helps save lives, Reed said, but it drives down burdens on the health care system. More patients catching illness early means fewer occupied beds, fewer busy doctors, less overhead for health care companies.

“I think the whole industry has the tiger by the tail. It’s this whole area that didn’t really exist a decade ago, and now it’s booming,” Reed said. “Some people say the market’s going to be $18 billion to

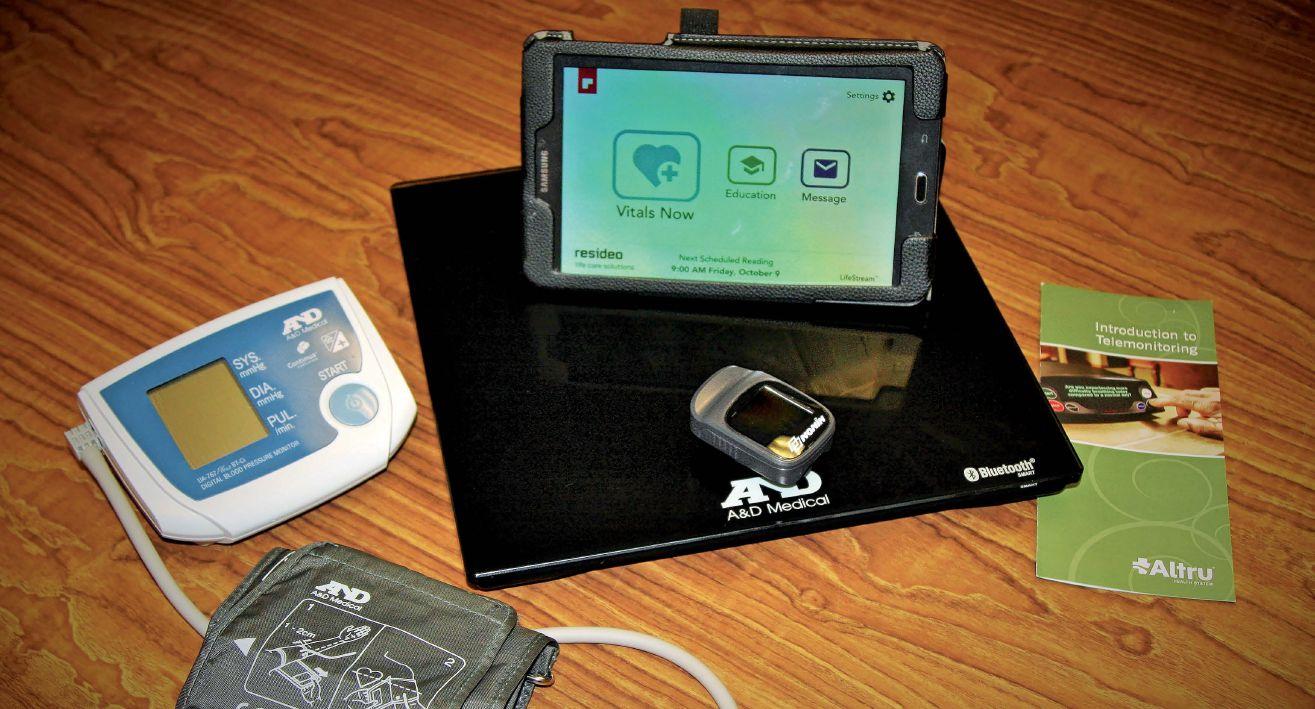

RESIDEO REMOTE MONITORING EQUIPMENT ALLOWS HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS AT ALTRU TO KEEP TABS ON PATIENTS AT HOME –WHETHER THEY’RE TRACKING NUTRITION OR VITAL SIGNS. IMAGE: ANDREW WEEKS/ PRAIRIE BUSINESS the end user in a few years, or $20 billion. The details may not really matter, because fundamentally it’s a big market, it’s booming, and it’s going to become absolutely enormous. It’s absolutely hard to track.”

This is no surprise to anyone who’s been watching consumer electronics, which have conditioned consumers to use wearables –Apple Watches, Fitbits and the like – for years. Those devices can measure heart rate and steps, and (for now) are typically thought of as strictly fitness devices. But they’re already on the wrists of millions of Americans, and health care is ready to capitalize.

Apple, which is debuting a subscription fitness service by the end of the year, is poised to build on that premise even further, bringing the commercial gym (minus the heavy equipment) into the middle-class basement. Suddenly, a brick-and-mortar gym is becoming a kind of middleman.

With the right amount of money, some consumers can take this to the extreme. The New York Times reports on the homes of Miami architect Kobi Karp, filled with sensors that clock the health of its occupants (examples include mirrors that can check vision and floors that can detect falls). For now, this is the provenance of the hyper-wealthy, and the Times notes that Karp’s homes typically sell for eight figures.

But the arc of medical tech bends toward a future where everyone has a version of this, or at least some kind of access to it. Blood oximeters, a finger-worn device that detects blood oxygen levels, have surged in popularity as consumers realize their readings could help detect a severe case of COVID-19. New versions of the Apple Watch come with the feature installed (though reviews have panned the feature’s accuracy).

But this is the model for the medicine of the future. At Mayo Clin- ic, doctors are already connecting with patients through a suite of at-home technology. When Dr. Deepi Goyal, a Mayo emergency medicine physician, got sick with COVID earlier this year, he joined what’s since become thousands of patients to pass through the clinic’s remote COVID monitoring program. Armed with tools like his own oximeter, thermometer and the like, he was able to virtually stay in contact with physicians at Mayo, who monitored how he felt day-to-day.

“I can’t even tell you what a sense of comfort having that program wrapped around me, when I was quarantining in a room by myself for two weeks,” he said during a recent Mayo virtual press conference.

Dr. Tufia Haddad, an oncologist at Mayo, describes this as the future of medicine: doctors sending home surgery patients, for example, and keeping tabs on their health from afar.

And it’s already arriving at hospitals beyond Mayo. For Altru Health System, headquartered in Grand Forks, N.D., specialists already rely on apps and bluetooth-capable devices to keep tabs on patients at home – whether they’re tracking nutrition or vital signs.

“I would say it would be very difficult if not impossible to do this 20, 30 years ago,” said Courtney Caron, Altru’s manager of case management. The analog version, with sheafs of paper and phone calls and in-person visits, would be far less efficient – and in a pandemic, far more dangerous.

For Reed, this is just the beginning.

A

PROMISE THAT MEDICAL WEARABLE TECHNOLOGY CAN PROVIDE FOR PATIENTS. AS TECHNOLOGY GETS SMALLER AND LESS EXPENSIVE, OBSERVERS SEE THEM BECOMING AN INCREASING PART OF DAILY LIVING. IMAGE: COURTESY OF MINNETRONIX

“If once a year, you got something in the mail the size of a postage stamp and you stuck it on your arm and you wore it a couple days, and it gave you a good picture of, how is your pancreas working? ... how’s your vascular health?” Reed said, imagining data instantly compared to other patients to predict trends in health. “If that cost you $25 a year, you’d probably do that.”

SARAH RASSIER, SUPERVISOR OF POPULATION HEALTH AND CASE MANAGEMENT, AND COURTNEY CARON, MANAGER OF CASE MANAGEMENT, DEMONSTRATE RESIDEO REMOTE MONITORING EQUIPMENT AT ALTRU HEALTH SYSTEM IN GRAND FORKS, N.D.

PATIENTS ARE LOANED BLOOD PRESSURE AND OXYGEN CUFFS TO KEEP TRACK OF THEIR VITALS, AND A TABLET TO USE TO RECORD AND SEND INFORMATION TO THEIR PROVIDER.

IMAGE: ANDREW WEEKS/ PRAIRIE BUSINESS