3 minute read

A better way to treat stormwater

By Andrew Weeks

Those who work to treat stormwater ask questions that the average person may not: Where does the water go? How will it be treated before it gets there?

Unlike industrial pollution, stormwater pollution is something humans contribute to as rainwater runs off roads and other hard surfaces, carrying with it chemicals, fertilizers and other contaminants. When stormwater hits streams and rivers, it carries with it any minerals and contaminants it has trapped.

This is where treatment plants come in, helping to ensure that stormwater is as clean as possible before it moves to its final destination.

But before the treatment plants, there were engineering companies that designed them.

Enter Houston Engineering Inc. (HEI), which has upped the cleaning process for urban stormwater with an automated pump-andtreat system.

How the Project Started

HEI and Maple Grove, Minnesota-based EPG Companies in about 2014 partnered with the Rice Creek Watershed District for a project at Hansen Park in New Brighton, Minnesota, to explore how to make treating stormwater more efficient at removing phosphorus and other components. Phosphorus is a natural mineral, but too much of it in standing water can cause algae blooms, which are harmful to humans and animals.

Up to that point, the district had used passive, or gravity-fed, systems that worked well when it stormed but were not as efficient at other times, according to Kyle Axtell, project manager at Rice Creek Watershed District. It wanted a system beyond just the traditional filter beds it was using, something more proactive that could treat stormwater not only when it rained but at other times throughout the season.

HEI had already been a partner with the watershed district for several years and this new interest allowed the company’s Dennis McAlpine, senior engineer, and Alex Schmidt, civil engineer, and their team to explore new possibilities.

Pump technology had already been around for a while, McAlpine said, and the iron-enhanced sand filters that the district had adopted were used on the passive scale. Relying on storm events – and gravity to direct stormwater into an infiltration basin – may be more cost-effective, but it doesn’t always work or is not as efficient.

“Stormwater pipes are underground, making it difficult to drain to a treatment feature on the surface given the limited amount of open space or ideal topography,” Schmidt explained in an article provided by HEI. “The common solution is to move the stormwater treatment underground. But underground treatment comes with a high price tag and its own difficulties, especially where infiltration is not possible.”

Schmidt said iron-enhanced sand filter beds require cycling of drying times to maintain their phosphorus capturing processes, but this doesn’t always happen with gravity-fed systems.

“If there are continuous flows for long periods after a rainfall, a gravity-fed IESF would be inundated for too long creating anoxic conditions, and actually, releasing phosphorus rather than capturing it,” he explained in his article.

But what if water could be pumped 24/7 and without the delays of waiting for Mother Nature to do her part? What if automated pumps could be controlled and set to cycle times that optimize the sand filters instead of relying on gravity?

WHEN WE STARTED, THERE WASN’T ANYBODY THAT WAS DOING ACTIVE PUMPING WITH MULTI-BED SYSTEMS. THERE WERE NO SYSTEMS WITH DEDICATED/ AUTOMATED CONTROLS SPECIFIC FOR THIS APPLICATION. THAT WAS SOMETHING NEW THAT WE HELPED DEVELOP.”

— DENNIS MCALPINE, SENIOR ENGINEER AT HEI

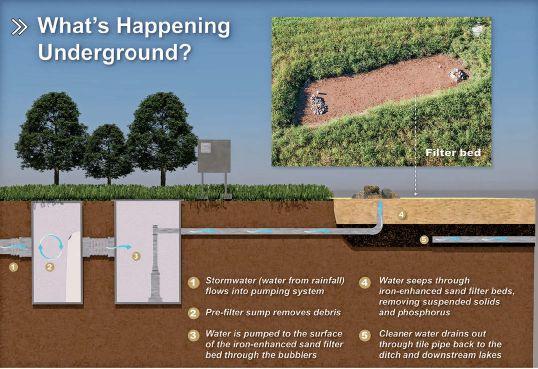

After its explorations, HEI came up with a successful model of an automated pump-and-treat system, which EPG Companies helped design with a keen focus on the system’s programming. The system uses iron-enhanced sand beds, but with its automated setup it allows the ability to pump at all times. It looks something like this: Stormwater flows into a pumping system, where a pre-filter sump removes debris. Next, water is pumped to the surface from the iron-enhanced sand filter beds through “bubblers.” Water then seeps through the beds to remove suspended solids and phosphorus, after which the cleaner water drains back out through a tile pipe back to the ditch and moves downstream. (See graphic.)

On the surface, the pond looks much like a bunker at a golf course, McAlpine said.

“We have a rock bed, we discharge water to the surface of the sand filter media through a bubbler – and the water cascades over a series of rocks (the bubbler) and fills up the bed,” he said. But the real magic happens beneath the surface with the automated system. “We can maximize that interface of stormwater and iron-rich sand mixture with our automated pumping system that manages stormwater dosing and rest periods.

“When we started, there wasn’t anybody that was doing active pumping with multi-bed systems. There were no systems with dedicated/automated controls specific for this application. That was something new that we helped develop.”

Some people may consider it just an irrigation system that pumps water from point A to point B, but McApline said it is much more than that.

“We developed our systems with a series of beds so we could maximize the dosing time and rest periods of stormwater pumping and have some redundancies if a bed went down,” he said. “There were some previous attempts at pumped systems with one bed and continued on page 15