11 minute read

On a Threshold -

3-D printing companies in Sioux Falls, S.D., and Fargo, N.D., are producing customized splints and prosthetic limbs affordably, efficiently and quickly

BY LISA GIBSON

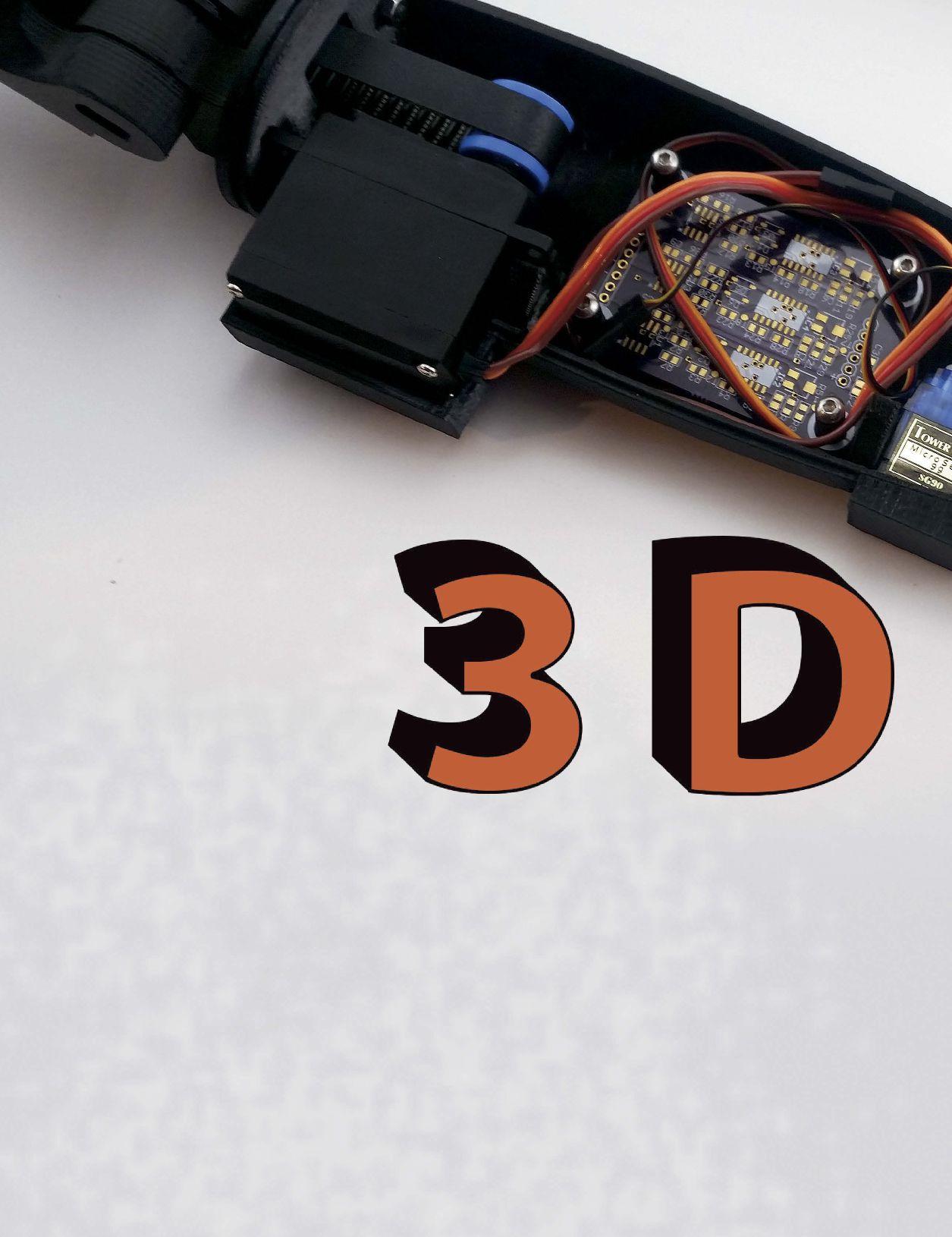

Protosthetics in Fargo, N.D., created this myoelectric prosthetic arm with a 3-D printer. It responds to the body’s electrical signals for joint control and can be easily customized for specific patient needs. IMAGE: PROTOSTHETICS

Harlan Temple farms 240 acres of beans, corn and alfalfa south of Sioux Falls, S.D., with the help of a tractor that fits his specific needs. Temple has cerebral palsy and gets around using a wheelchair. For the past two months, he’s also been using a 3-D printed brace that supports his left arm, wrist and hand. He calls himself the guinea pig, being the first patient to have and use a 3-D printed orthotic device produced by 3DVHB LLC, a Sioux Falls company founded in 2002 by Lowell Hyland, a retired Sioux Falls allergy physician, and Duane Burman, a former 3M medical products manufacturing engineer.

Patients with cerebral palsy are perfect candidates for orthotics — braces or splints that support limbs and joints — according to Arlen Klamm, physical and occupational therapy mobility specialist with LifeScape, a nonprofit health service for patients with disabilities, also based in Sioux Falls. 3DVHB teamed up with LifeScape in 2002, with the goal of helping Klamm ensure his patients receive customized, reasonably priced orthotics that can be easily tweaked and experimented with, Burman says. “We want the orthotics to be prescriptive,” he says. “We want them to fit into a rehabilitation or a restorative pathway that Arlen would define for a given patient.”

For some patients with cerebral palsy, for example, Klamm says one group of muscles in the arm and hand is much stronger than the opposing group of muscles, resulting in a positioning of the limb where all joints are flexed. “And that’s the position they maintain, sometimes all day long and all night long. The splint allows us to support the hand in the opposite position so they can maintain their range, because keeping the limbs flexed for such a long period of time, eventually the joints lose the motion and they're stuck in that position.”

“It stretches my fingers,” Temple says of his 3-D printed splint. “It really fits perfectly. Previously, they would need to heat up plastic in a frying pan and mold it to my hand. ... My old brace broke, so that’s when they asked me to be the guinea pig. It is lighter and identical to my old brace. Saves so much time. It is more cost efficient.”

Perfecting the Process

Temple is right. The process of 3-D printing an orthotic is much more efficient and simple than producing it the traditional way, Burman says. Klamm says the printing process greatly reduces the amount of craftsmanship and talent required to produce orthotics or prosthetics, allowing therapists without those skills to make them for their patients.

The acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) plastic material used by 3DVHB to make the devices also stands up to heat better than plastics used in traditional orthotic devices, which protects against melting and harsh wear and tear, Burman and Klamm say. Klamm says most orthotics have about a one-year lifespan, but this technology likely will prolong that, he hopes. Since Temple is the first test subject and he has had his device only a few months, the lifespan is a theory for now. “What I expect is that these will hold up better,” Klamm says. “So you’ll have longer use periods, so over the lifetime of the person, you have fewer orthotics. I also believe these are going to be easier to maintain because of the types of materials they’re printed from.”

Protosthetics in Fargo, N.D., also is working on 3-D prints, focusing more on prosthetics than orthotics. Founder and Chief Futurist Cooper Bierscheid, who graduated from North Dakota State University in December with his degree in manufacturing engineering, also emphasizes the ease of production in 3-D printed devices. In traditional production, molding techniques, injection mold tools and other parts of the process cost money and take time, he says. “If you have people with all different sizes of sockets, you need a new tool for each of those sockets and that gets very costly.” With its software, Protosthetics can digitize a person’s limb and replicate the socket in a printed device within 48 hours, he says. “It gives the chance for people who weren’t able to afford the devices before to own one.”

As part of a senior design project at NDSU, Bierscheid teamed up with fellow students to design the printed artificial limb (PAL), an above-the-elbow prosthetic arm, for a professor’s 4-year-old grandnephew who has no elbows or forearms. The prototype designed for the young boy is myoelectric, meaning it uses the body’s electrical signals to control movement of the joints in the prosthetic. Protosthetics was born from the project, and the company, now led by Bierscheid and partner Josh Teigen, is conducting beta testing on PAL, building its case study around the 4-year-old.

The 3-D printing industry is based on mass customization, with the ability to quickly and efficiently fit unique needs, Bierscheid says. Children will grow out of their prosthetics and orthotics, and 3-D printing — or by its technical name, additive manufacturing — is a great way to continue providing affordable upgrades without remaking motors and electronics. “That’s the great thing about additive manufacturing is we can scale as the child grows. … We simply have to reprint the shell of the arm.

“3-D printing has the chance to change a lot of industries but especially prosthetics and orthotics because of the mass customization,” Bierscheid says.

Protosthetics will sell PAL, once it’s ready for commercialization, for between $6,500 and $8,000, depending on size, colors and add ons, Bierscheid says. The company also unveiled its new product, the Amphibian, in June. The device is a secondary prosthetic leg, Bierscheid explains, adding there’s a large demand on the market for such a product. The leg can be used on the beach, in water, mud or dirt, where a primary prosthetic normally would not be worn. The Amphibian will be sold for less than $1,000 and can be billed through insurance, significantly helping to achieve Bierscheid’s original goal of making 3-D printed products that will help people.

To the Future

Michael Filloon, prosthetist and orthotist for Essentia Health in Fargo says 3-D printing holds great promise for orthotics and upper-body extremity prosthetics, mainly because of the ease in production. “I can do it. Therapists can do it. Anyone can do it. Is it a benefit? Yes. A big benefit.”

Filloon has no patients with 3-D printed orthotics currently, but said he would be open to it. “If the technology would allow for the specific stuff that I do in a general day, if it was specific to what I was using and it worked quicker, I would definitely use it in a heartbeat.” He says he’d venture a guess that 3-D printed orthotics will grow in usage.

But 3-D printing of prosthetic legs still hasn’t gained fieldwide acceptance among his colleagues, Filloon says, based on the main limitation of a strong enough material to hold up under high-stress situations. Bierscheid says 3-D printing has gotten a bad reputation for being poorly suited for load-bearing applications, but Protosthetics can print 30 different kinds of plastics, enabling the Amphibian to to be crafted of high-strength nylons, strong polymers and coatings, as well as pylons and rods to provide a stable skeleton.

Improved Outcomes

As the 3-D printing technologies for both orthotics and prosthetics move forward, people who need those devices will see improved access to them. The next step for 3DVHB and LifeScape is to help adult patients successfully enter purposeful work environments where they can create or assemble parts, such as windows or pallets, relying on the support of their orthotics, Burman says.

Klamm adds, “I can envision what we’re doing resulting in improved outcomes for not just the people that I’m seeing, but therapists that are seeing other people wherever they reside, in that it’s going to allow therapists who haven’t been able to provide a high-quality, very customized splint to their patients because the process itself is going to be easier to do that.”

From the farm, Temple says 3-D printing “absolutely” is a promising technology for him and other people with physical limitations. “I think it’s really exciting. Technology fascinates me. One thing blossoms into another. My mind goes wild.” His next idea is a custom-fitted seat for his tractor. PB

Lisa Gibson Editor, Prairie Business 701.787.6753 lgibson@prairiebusinessmagazine.com

BY KAYLA PRASEK

With ever-changing technology comes the pressure for businesses to continually implement the newest trends. Regional banks are not immune to that pressure, but representatives from Gate City Bank, Bremer Bank, Alerus and Great Western Bank all say they listen to their customers while also taking a wait-and-see approach before committing to anything new.

All four financial institutions have branches throughout the Midwest and have implemented the two biggest trends in financial technology — EMV chip cards and mobile banking.

“Twenty years ago, what we had for channels were ATM, debit cards, checks, wiring money, local branches and credit cards. That was it,” says Maureen Jelinek, executive vice president and director of technology at Gate City Bank, headquartered in Fargo, N.D. “A wide array of things have happened and the technology landscape has changed so fast in 20 years. There are new products almost daily.”

Mobile Banking

Jelinek says Gate City’s biggest growth has been in mobile banking. “You don’t need a computer anymore, so our big focus is really on mobile,” she says. “We’re working toward being able to open accounts on our mobile app. You can now register for mobile banking via your mobile device. You can make mobile deposits and receive mobile banking alerts. It’s very convenient for our customers.”

Bremer Bank, headquartered in St. Paul, Minn., also has a mobile app that includes the ability to deposit checks, transfer between accounts and pay bills. The bank also recently launched a new website, which it built from the ground up to be respon- sive to all devices, from desktop computers to tablets and smartphones, says Tom Grahek, chief information officer for Bremer.

Alerus, headquartered in Grand Forks, N.D., debuted its consumer mobile app in 2013 and added mobile deposit in 2015. Also in 2015, Alerus rolled out mobile business banking, which gives business owners the ability to approve pending wires and financial transactions and look at their financial history, says Kristine Lunde, deposit product specialist lead at Alerus. The bank recently rolled out mobile deposit to its business customers, which allows those customers to make deposits into their business accounts while on the go. “You no longer always have to be in the office to check on your business accounts,” Lunde says.

Great Western Bank, headquartered in Sioux Falls, S.D., recently made a large investment in its online and mobile banking platforms, says Tim Schmidt, senior product manager at Great Western. “The new platforms are integrated and much more usable than what we previously had,” Schmidt says. “They have an updated look and feel.” Great Western rolled out the new platforms to new customers in April and is currently rolling out the new platforms to existing customers, which the bank expects to have completed by Labor Day. The new platforms include bill pay and mobile deposits, and a series of enhancements will follow in the coming months to introduce Turbo Tax, account integration and retirement plan management.

Great Western Bank also introduced a new commercial banking program in January, which provides more functionality for online banking as well as a mobile channel and a channel to send transaction requests straight to the bank for a more direct process, Schmidt says.

Education and Support

Alerus, Gate City, Great Western and Bremer have all either implemented or are in the process of implementing EMV chip cards. Alerus rolled out chip cards in early 2016 and the process is complete at this point, says Karna Loyland, chief deposit officer at Alerus. “EMV chip cards provide significantly better security and have wider acceptance worldwide for our customers who travel.”

Part of rolling out new technology, such as the EMV chip cards, is educating customers while also continuing to support older technologies, Jelinek says. Gate City is almost done rolling out its chip cards but Jelinek stresses that “the bank needs to continue supporting all the available channels,” which, for example, means continuing to support the magnetic swipe strip while also educating customers on how to use the chip. “As technology changes, our customers rely on us to teach them how to keep up, but at the same time, we’re at the mercy of the merchants to switch to the new technology on their end,” Jelinek says. “We have to explain all the options merchants might have and that they may not always be able to use the chip everywhere they go.”

Bremer Bank has also finished implementing EMV chip cards, while Great Western Bank is planning to have all cards moved over by the end of the year, Schmidt says.

Several of the banks have implemented other technologies as well. At Alerus, business banking customers can download Trusteer Rapport, a free service the bank recommends to protect against cybercriminals and fraud, Lunde says. The bank also runs behavior analytics on business accounts and alerts those customers as soon as a red flag goes up. Alerus has also “made a concerted effort” to make all documents available electronically and has implemented electronic signatures, Loyland says. “This changes up the business relationship we have with our customers.”

Bremer Bank made Apple Pay available to its customers earlier this year after customers requested it, Grahek says. The bank is also working on implementing Android Pay and Samsung Pay. “As more and more merchants become Apple Pay-enabled, it’ll drive customers to use that option,” Grahek says.

Implementing Technology

Bremer’s decision to add Apple Pay after customer requests is a common theme among these four banks. As Grahek says, “we want to be a relationship-based bank, so we listen to our customers and monitor the available technology. We always assess where the technology is because we don’t want deployment issues. Sometimes when a product is brand new, there are a lot of issues, so we may wait until the technology is more mainstream.”

At Alerus, “a lot of customers’ expectations for technology are driving changes,” Loyland says. “Our customers have expectations, and those expectations have pushed the financial industry to keep up with all the technology.” At the same time, the bank is aware that it is possible to have too much change too quickly. “We have to look at ‘how much change are we asking for from our customers?’” Loyland says. “Some of it is intuitive, but some of it takes more time to learn so that can take a longer rollout.”

Schmidt says Great Western prides itself in customer service and sees its online channel as important to customer engagement, which is part of the reason the bank has taken its time migrating customers to its new online and mobile platforms. “It takes a lot of pre-planning and internal and external communication. Our customers need to be aware of what’s coming and how to access and use it.”

Jelinek says Gate City Bank is always watching the latest in financial technology but also knows “we can’t implement everything, so we figure out what’s best for our customers. Security is our highest priority, so as we’re offering more channels, we need to make sure each one is secure. We also have to educate our customers about the importance of security. We work at trying to keep our customers educated about phishing and ransomware. If they fall victim, it could put their information at risk and could compromise their accounts.”

Fighting fraud is a constant for banks, and updating technologies can play a role in that, Grahek says. “Security is very important. We’re consistently investing in the most secure platforms.”

Lunde says it’s “essential we keep pace with technology, but we also have to build the security behind a platform and make sure it keeps everything safe.” Alerus partners with vendors to build its products so the bank must also do its due diligence on those vendors to ensure its customers’ security, she adds.

Thanks to evolving financial technology, Jelinek says there is essentially no reason customers would ever need to close their accounts if they move to a community where there isn’t a branch of their bank. “We can process loans online. We’re working on implementing electronic signatures. You don’t need to come into a branch to do your banking anymore.” PB

Kayla Prasek Staff Writer, Prairie Business 701.780.1187 kprasek@prairiebusinessmagazine.com

“Prairie Business magazine is a great source for a comprehensive regional approach to business news. e magazine o ers a diversity of information. In economic development, it’s important to have a solid overall understanding of the industry sectors regionally. Reading Prairie Business is an excellent source of information in that regard.”

- Jim Gartin