12 minute read

Training workers and drawing tourists A Q&A with North Dakota Gov. Doug Burgum about key elements of his vision for the state

EDITOR’S NOTE:

In a r ecent interview with Prairie Business, North Dakota Gov. Doug Burgum talked about two business-related proposals that he’s making for the 2019 legislative session: career academies (which are meant to help solve the workforce shortage), and the proposed Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library, a potential tourism boost.

Here is a transcript of the governor’s remarks in our interview. The transcript has been edited for clarity and length.

A.BURGUM: At the career academy in Bismarck, students are taking their first year of their associate degree while in high school and the second year as freshmen. Lt. Gov. Brent Sanford and I were touring there a month ago in this power-plant management class, and there are young kids who’re in the equivalent of October of their (college) freshman year.

We asked the professor how it’s going. He said two of his kids already have job offers; they are going to get hired for $72,000 a year out of his class before they even finish one year of college with no debt.

That program really was both funded and started by the Bismarck Public School system. We’d like to see career academies in other communities as well, so we put in $30 million in the budget for career academy grants.

From a context in understanding the education discussion in North Dakota, one of the largest employers in most of our communities is the public school system. You have Bismarck, Fargo, West Fargo public schools -- these are organizations that are getting close to 2,000 people. We have 15 or so school districts that are bigger than some of our universities in terms of staff and students.

There are 11,000 or 12,000 students in Bismarck, so we have huge K-12 groups, too.

So, in making the career academy proposal, we’re saying, “Here is $30 million from the state, but you can partner with local political subdivisions, including K-12 organizations.”

Some of these K-12 organizations can go out and bond and build new buildings. They have all kinds of freedoms the universities don’t have. Why? Because they have local governance.

We have 180 K-12 school boards. We have one board trying to run higher education in the whole state. I think there is an opportunity for that collaboration.

So regarding the grant proposal, Grand Forks, Minot, Dickinson and Fargo are all great places to start because they all have huge numbers of high-skilled jobs available that require only an associate degree.

A. Q.

WHO SHOULD APPLY FOR GRANTS FROM THE $30 MILLION? TO WHAT AGENCIES OR BODIES WILL THAT BE DISTRIBUTED?

BURGUM: Ultimately, it will be a consortium. The career academy in Bismarck started with Bismarck Public Schools years ago, and they then engaged with Bismarck State College. The two of them jointly run it, with joint faculty and joint students.

In Grand Forks, there is a trade school in East Grand Forks, but it’s not part of our system, and you have Lake Region State College, a two-year school that is not far away. Down I-29, you have the North Dakota State College of Science, which has the ability to project capability up to the northeastern part of the state.

Q. SO YOU ENVISION THAT THIS COULD HAPPEN AT A FOUR-YEAR UNIVERSITY LIKE UND?

A.

Q. SO IT LIKELY WOULD BE A PARTNERSHIP? Q.

A.

BURGUM: I think so. A.

Q.IS THERE A WAY TO SCALE IT UPWARD TO THE FOUR-YEAR UNIVERSITIES?

BURGUM: Absolutely. For example, Arizona State University started a charter school. Then after that, the university said, “What would a digital high school look like?”

So now they have a digital high school, and we found there are three kids from North Dakota going to ASU, doing their high school online.

CAREER ACADEMIES LIKE THE ONE AT ARIZONA STATE DO NOT CURRENTLY EXIST AT FOUR-YEAR SCHOOLS IN NORTH DAKOTA?

A.

BURGUM: No. There are some partnerships between our two-year schools, and they are doing innovative stuff around careers. Also, they have connections with high schools because of dual credits that are being offered. Some students in Grand Forks are taking a dual credit class at Lake Region State College and earning college credit, for example. And Lake Region is getting paid for that through the formula that we have.

BURGUM: It could. Or UND could say “Hey, we want to do this in conjunction with our nursing program, with North Dakota State College of Science and Grand Forks high schools.” Then those three could form a partnership or collaboration and go. And then you throw in the private sector, because the wind guys say they’ll give you equipment if you can train guys to help repair wind generators. And all of a sudden, you have a wind lab that the private sector paid for. That’s part of where the funding can come for these things.

At a career academy, people want to hire these kids before they even graduate. They are willing to put the equipment in there as long as someone else can provide the accreditation, the capability and teaching. They want to hire the product.

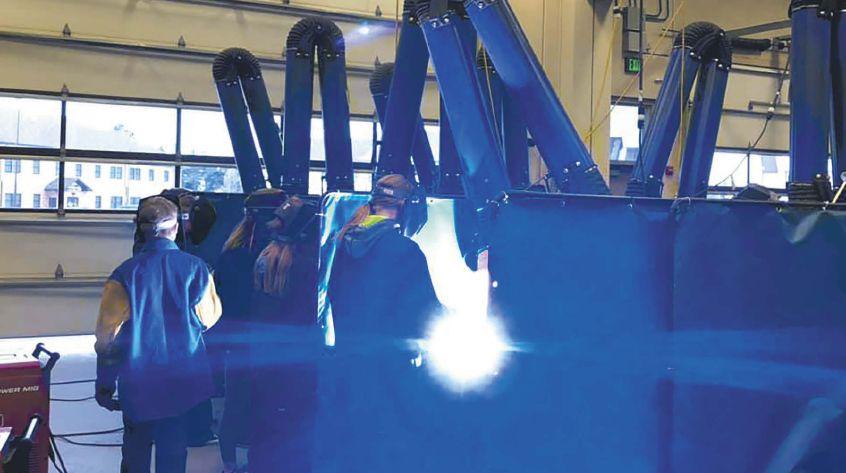

EIGHTH GRADE “STEPPING INTO STEM” STUDENTS FROM BISMARCK, N.D., MIDDLE SCHOOLS TRY WELDING AS THEY ENJOY A RECENT DAY OF HANDS-ON LEARNING AT THE BISMARCK CAREER ACADEMY. GOV. DOUG BURGUM HAS PROPOSED A GRANT PROGRAM TO ENCOURAGE OTHER NORTH DAKOTA COMMUNITIES TO SET UP CAREER ACADEMIES OF THEIR OWN.

IMAGE: BISMARCK PUBLIC SCHOOLS

Q.

A.

WHY THE PUSH NOW FOR A THEODORE ROOSEVELT PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY?

BURGUM: The Park Service has basically put no money into the national park in North Dakota since the 1960s. Whether it’s the beautiful view that we have at Painted Canyon – that’s a 1960s rest stop with an amazing view – or the park entrance building, a cinder-block construction, you have 50 years where nothing has happened.

Today, they are willing to make a substantial reinvestment into Theodore Roosevelt National Park. So, if we are going to step up and do this library, we have a two-to-one match, the same as the Challenge Grant.

It’s $50 million proposed, and it will take $2 of private for each dollar of state money, but the private can come not only from individual donors. There also are a number of other groups, such as the Boone and Crockett organization, which was founded by Theodore Roosevelt; the Explorers Club of New York, of which he was a member; and the largest one being the National Park Foundation, which is an independent foundation which has got some of the nation’s biggest executives and wealthiest individuals serving on that board, and they are contemplating a $1 billion capital campaign to support the national parks as a partner.

There are 60 national parks, but only one that’s named after a person. They would have as a flagship of that campaign: “Hey, donate to us and we’ll go improve the parks, and guess what -- we’re going to do a presidential library for the guy who founded the Park Service, in one of our parks.”

SO THIS SITE IS PROPOSED AT THE PARK VS. DICKINSON OR MEDORA?

BURGUM: The site discussed with the National Park Service is at the entrance to the park, effectively in Medora. It would be a private project on federally owned property.

They have an example of having done that at Gettysburg. There is a $100 million museum and visitor center that is run by a foundation, but inside that building, you have uniformed Park Service individuals who are there selling park passes.

Q. IS THERE NO PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY, AT PRESENT, FOR TEDDY ROOSEVELT?

A.

BURGUM: No, there is not. And it’s astounding because he’s written more books (at 142) than anybody else, and he has 150,000 documents. We have digitized 50,000 of them already at Dickinson State University, so it’s astounding to me that this hasn’t happened yet.

Q.

INSIDE OR RIGHT OUTSIDE THE PARK?

BURGUM: If we’re drawing a map of Medora, the land outside the park is very expensive because there is very little developable land, and there are lots there that might be $1 million. We would love it if it was inside the park, and the Park Service said, “Here is some land for it, you guys have at it.” That could be an inkind contribution of $5 million just on the site alone. Right inside the park area, they have a maintenance shop that is there and a bunch of one-story housing. All that would get blown up. In their plan, they would go to multi-story housing someplace else that’s not on the multi-million-dollar beachfront in Medora, and they would pick up the maintenance facility and put it out in the middle of the park somewhere. That would free up all of that space for a campus right there.

Q.

A. A.

DID THE INTERIOR DEPARTMENT HAVE ANY ROLE IN DECIDING TO MOVE IT FROM DICKINSON TO MEDORA?

BURGUM: No.

By Tom Dennis

GRAND FORKS, N.D. – Consider the insulin pump.

To develop a modern insulin pump, professionals from several disciplines must work together, said Les Olive, director of campus planning at South Dakota State University in Brookings, S.D.

The task needs physicians to set dosages, mechanical engineers to build a pump, electrical engineers to power that pump and computer engineers to etch the unit’s controls onto a chip.

“And the thing is, modern agriculture problems need the same kinds of relationships,” Olive said.

“For example, you need plant scientists, soil scientists, engineers and computer scientists to come together to find a way to administer herbicide in a more precise and controlled fashion than has been done before.”

That’s why SDSU’s new Raven Precision Agriculture Center is being designed with collaboration in mind, said Olive and John Killefer, dean of the SDSU College of Agriculture, Food and Environmental Sciences.

So, faculty members will be officed next to professors from other disciplines, not their own. Classrooms will sit students facing each other, not the front.

And students moving between those classrooms will traverse common areas, not hallways. Food, whiteboards and comfortable seating in the common areas will encourage more interaction.

“We’re talking about our facility as an innovation ecosystem,” Killefer said.

“We’re trying to get folks from multiple disciplines, as well as students, to address a common problem and attack it from multiple directions. ...

“We want people to mingle and share ideas.” Colleges and universities throughout the Prairie Business region want the same. And for students, the college experience that’s resulting is very different than the one their parents may have encountered.

SCALE-UP

Consider a biology classroom at North Dakota State University, a classroom whose design – called SCALE-UP – captures the difference between old and new.

SCALE-UP stands for Student Centered Active Learning Environment with Upsidedown Pedagogies, said said Jennifer Momsen, associate professor. And unlike many acronymed academic endeavors, this one represents real change.

In SCALE-UP classrooms, students sit at round tables of about nine students each. That’s the first thing a visitor who’s used to a traditional classroom notices.

The second thing: Very little lecturing is happening, even for courses that used to be delivered in lecture form.

Instead, “we’re talking about a ‘flipped classroom,’ in which students learn the basic material outside of class,” Momsen said.

“So, they’re coming to class prepared.” Then in class, Momsen probes to gauge students’ mastery of the material, delivers “mini-lectures” on key points and assigns problems, which the students usually solve in groups.

Which brings up the third thing a visitor notices: how often students use whiteboards to diagram what they’re doing.

The SCALE-UP system works, Momsen said. “There has been a lot of research looking at collaborative learning, and it has found that learning is a social activity,” she said.

“So, anytime we can talk to each other, we’re going to learn better. … We get bored if we listen to a lecture for too long. But if we can pause to talk our ideas out with a neighbor, it goes a long way toward keeping us engaged.”

By the way, the largest SCALE-UP installation in the world is at the University of Minnesota, according to scaleup.ncsu.edu.

That U of M facility boasts “10 Active Learning Classrooms ... holding anywhere from 27 to 126 students,” the website reports.

“One third of all Minnesota undergraduates took a class in one of the new rooms within a year of opening.”

Engineering Collaboration

Consider the charge given by engineering firms: Send us engineers who know their fields, can solve real-world problems and work well on teams.

The University of Mary in Bismarck, N.D., designs its program to do just that.

Currently, the university offers engineering degrees in partnership with the University of North Dakota. The renovation of an existing building into a full-scale, on-campus School of Engineering will start in the spring.

Linking the current and future programs will be a focus on collaboration, said Terry Pilling, engineering program director.

“For example, our faculty don’t have separate offices,” he said.

“We have one big office that’s used by all of our engineering faculty from all of the different disciplines. … So there is constant collaboration among the members of our department.”

Likewise, there are whiteboards “all over the place,” both inside and outside of class. In fact, “we don’t have any classes where students sit at a traditional desk and watch a PowerPoint presentation, for example. They’re on their feet and active much of the time.”

Furthermore, “our senior design projects are combined,” Pilling said.

Engineering students across America complete senior-year projects, typically in their own field.

“And we have design projects at lower levels –junior design projects – that work like that.

“But in our program, our seniors have to design projects that involve all of the different engineering specialties,” Pilling said.

“They delegate tasks depending on each others’ expertise, and then the whole thing comes together, which is basically the way the real world works.”

Innovation In Medical Education

And consider this: From their first days of medical school at the University of North Dakota’s School of Medicine and Health Sciences, prospective doctors see patients.

It’s hard to overstate the importance of that change.

“When I was in medical school, we had almost 100 percent lectures for our first two years, and the educational experience was focused on teaching,” said Dr. Joshua Wynne, the UND school’s dean.

“That teaching consisted of a ‘data dump’ from from the professor’s mind to the students’ minds, and the criterion of success was memorizing facts.”

Fast forward to today, when “the focus is on the learning that the students do, which is active and collaborative. … What our students now learn is how to work with each other, and how to use each other to both formulate questions and then access data sources to get answers.”

Three quick examples:

• First, “I greet the students on their first day of medical school, and at 9 a.m., I present a patient dilemma to them,” Wynne said.

“They work on the case, which involves a child. … Then they meet Ben, who was the child and is now a student at UND. They chat in the auditorium with Ben, and he tells them about his experience.

“This is a dramatic change from the way I learned,” Wynne said.

• Second, “the first time I delivered a baby, it was with a real mother and a real baby, with a full doctor standing behind me,” Wynne said.

“That’s not the way our students learn now. They go into a simulation laboratory, where a manikin can ‘give birth.’ The students can deliver the baby and practice with the manikin before they ever treat a real-life patient.”

By the way, these manikins can blink, talk, cry and have a cardiac arrest in front of the student, Wynne said. “All of that can be programmed in.”

Live actors from the community sometimes play the role of patient, too. “Then we ask those ‘patients’ to grade the student on the interaction,” Wynne said.

“One time, the ‘patient’ said to the student, ‘Sarah, I just want to tell you that when you gave me the bad news, you put your hand on my shoulder, and that made all the difference to me because you established that human contact. Keep that up.’”

Sarah won’t soon forget that advice and likely will follow it throughout her career, Wynne said.

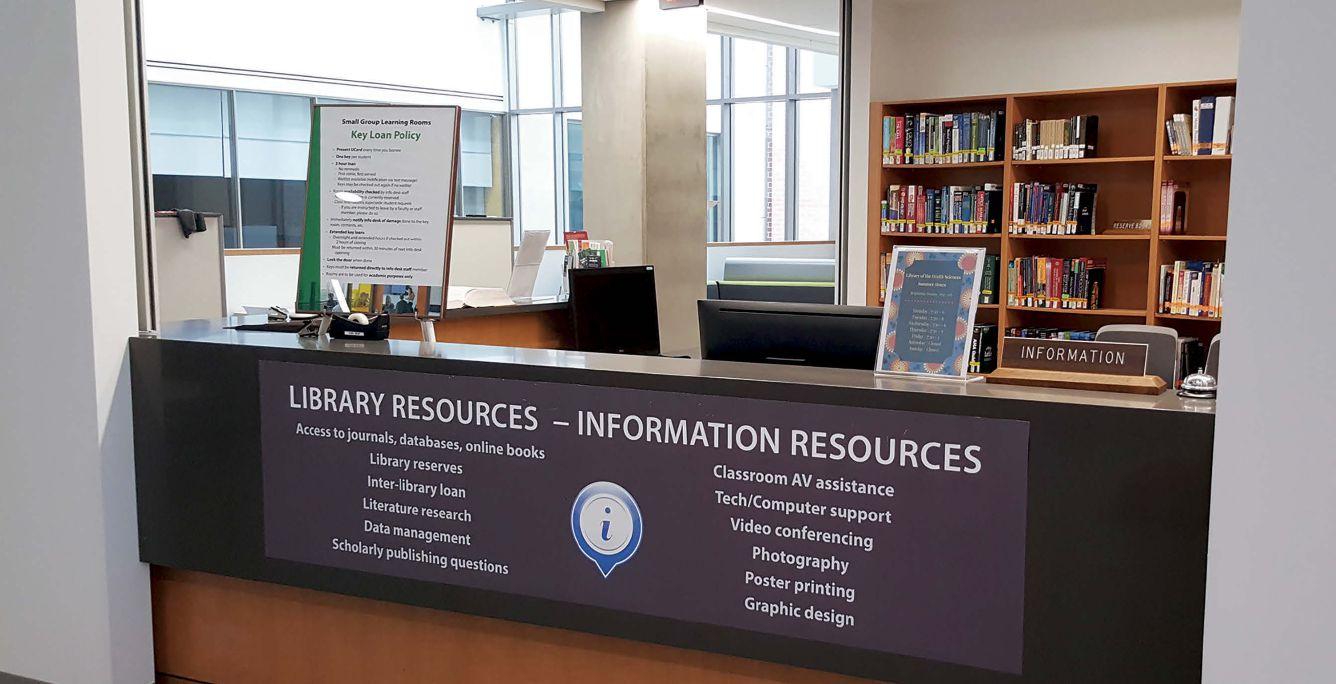

• Third, the changes extend to the school’s new building, which opened in 2016.

“Again, when I went to medical school, there was a separate building that was the library,” Wynne said.

“It was many stories high, and it was filled with thousands of journals and books.”

In the medical school’s new building, in contrast, the library consists of six linear feet of books.

“Now let me emphasize, we still have the same number of librarians,” Wynne said.

“It’s just that they are embedded with the students and the faculty, helping them or teaching them to do searches of the literature that’s available online.”

The bottom line is that if students simply are memorizing facts, “they’re going to be behind the eight ball,” Wynne said.

“That’s because the facts change. We refine our recommendations based on new knowledge. And the best way to have continual learning is to make students aware of that, so they can access that data and those findings and incorporate them into their practices.”

Tom Dennis Editor, Prairie Business 701-780-1276

tdennis@prairiebusinessmagazine.com