10 minute read

Law school oasis

By Tom Dennis

GRAND FORKS, N.D. – Esquire Never. Inside the Law School Scam. Law Lemmings. Third Tier Reality.

And a few other names that can’t be printed here.

In parts of America, the Great Recession hammered the economics of practicing law, and underemployed lawyers’ angry “scam blogs” (such as the ones listed above) have swung mallets at the situation ever since.

“My goal is to inform potential law school students and applicants of the ugly realities of attending law school,” declares one, with the alleged “reality” being “your huge investment in time, energy and money does not, in any way, guarantee a job as an attorney.”

Make no mistake, the national numbers have been sobering. Between 2008 and 2011, some 15,000 attorney and legal-staff jobs at large firms “vanished,” the New York Times reported. Unemployment among lawyers in some markets rose, applications to many law schools dropped. More recently, a few law schools have merged or even closed.

But …

That’s not the whole picture.

In North Dakota, South Dakota and western Minnesota, it’s not even very close.

“I have never had anyone say to me there are too many lawyers in North Dakota,” said Tony Weiler, executive director of the State Bar Association of North Dakota.

“Believe me, lawyers love to voice their opinions. And I think if they all of a sudden started to not have any work, we would hear about it.

“Based on that and other factors, I know lawyers are busy, and there is demand.”

Eric Schulte, former president of the State Bar of South Dakota and a partner in the law firm of Davenport Evans in Sioux Falls, S.D., agreed.

“There really are opportunities to practice law in South Dakota,” Schulte said.

“I don’t think it’s the same situation as some of the bigger markets that you find on the East and West coasts. I think that our economy tends to be robust and healthy here, and I can tell you that from my perspective, we need more lawyers in South Dakota.”

Like other key elements of the economy, the legal profession in Prairie Business’ circulation area largely avoided the national recession’s most serious effects, interviews and statistics suggest.

Don’t misunderstand. As with the region’s housing market and household incomes, a big reason why the lawyers’ jobs didn’t “bust” is that they’d never “boomed” in the first place.

Instead, the region’s always-more-modest market for lawyers simply improved steadily.

That “always more modest” description is important to understand.

“If you’re thinking about a market like New York or Chicago, or if you’re expecting your first job as a lawyer to pay over six figures, you have to understand that that’s not realistic for North Dakota,” said Kathryn Rand, dean and professor at the Grand Forks, N.D.-based University of North Dakota School of Law.

“That’s not our character, that’s not our goal. We’re upfront with students that this is a different market and a different path.”

And in both North Dakota and South Dakota, that path tends to result in a first job out of law school that pays roughly $50,000 to $65,000.

But the context is vital when considering those sums.

For one thing, new lawyers who’ve worked hard can be reasonably confident of finding a job in that range. “Definitely in South Dakota, there are jobs for our grads,” said Devra Sigle Hermosilla, director of career services at the University of South Dakota School of Law in Vermillion, S.D.

“At graduation, about 70 percent of the Class of 2017 was employed already.”

And 10 months after graduation, some 91 percent of USD Law’s Class of 2016 had jobs for which a law degree was either required or preferred, a measure of job quality. That’s well above the national average, which is about 75 percent.

At the University of South Dakota School of Law, MacKenzie Lawrence ’18 (speaking) and Brian Griffin ‘18 (left sitting) and Zachary Meisler ’18 (right sitting) practice trial techniques in USD Law’s Courtroom. The law school’s employment rate for new graduates ranks above the national average.

IMAGE: USD SCHOOL OF LAW

For another thing, USD and UND are two of America’s least expensive nationally ranked law schools. Law students at New York University pay about $64,000 a year in tuition and fees; for North Dakota residents at the UND law school, the comparable figure is about $12,000.

As a result, graduates leave the UND and USD law schools with comparatively low debt – about $66,000 at UND and $57,000 at USD, far lower than the $160,000 that many graduates of private law schools incur.

That’s hugely important. “For a new lawyer, there’s a big difference between owing tens of thousands of dollars and owing hundreds of thousands of dollars,” said Mac Schneider, a Grand Forks attorney and former North Dakota state senator.

A lawyer who owes little can choose lower-paying options such as assistant state’s attorney, the nonprofit sector or rural practice. A lawyer who owes lots knows it’s corporate law or bust.

Schneider graduated in 2008 from the Georgetown University Law Center in Washington, a pricey private school. “Without scholarships, I would have graduated with extremely high debt, as many of my classmates did,” he said.

2017 UND School of Law graduate Elle Molbert receives her academic hood at the law school graduation ceremony in May 2017.

Molbert currently works for the Ohnstad Twichell law firm in Fargo, N.D.

IMAGE: UND SCHOOL OF LAW

“There would have been no way I could have come back to North Dakota and become a state senator.” Instead, a Big Law position in a place like New York, Washington or Chicago would have been his only option, Schneider said.

Schneider has worked in private practice in North Dakota since graduation, which means he’s seen nine classes of new attorneys graduate from the UND School of Law. He’s met many of those graduates in his practice and his Senate work, and his conclusion about the job market is clear:

“If your goal is to work at a ‘white shoe’ law firm, then maybe go somewhere else – Northwestern, or someplace like that,” he said.

“But in our region, you can be an excellent attorney and make a good living with a North Dakota education. It’s such a public benefit to have a law school that provides these benefits, and the educational opportunities that it offers are a really good deal.” PB

Tom Dennis EDITOR,

Pick Up The Flu

(surfaces spread germs, just like people)

Clorox® disinfecting products kill 99.9% of germs - to help offices stay healthy.

We all know sneezing, coughing colleagues pass along germs. But so do the objects they touch. Don’t worry. Clorox® disinfectants wipe away illness-causing germs. So keep them on hand - and help keep your office health and happy. And productive.

Use as directed.

Available at:

By Tom Dennis

GRAND FORKS, N.D. – It’s possible to think of the changes facing North Dakota’s higher education governance system in terms of commissions and legislation.

But it’s easier and a lot more fun to think of them in terms of movies.

So here goes:

As a new higher-ed task force starts meeting to consider potentially massive reforms, which movie best captures the shape of proposals to come:

“The Wizard of Oz”? “1776”?

“The Oregon Trail”?

Or “Star Wars: The Last Jedi”?

There’s a fair chance the reform model actually will conform to one of those plot lines, as we’ll explain. It’s our hope that the explanations help task force members sharpen their thinking, too.

A new, 15-member commission – appointed and chaired by Gov Doug Burgum – will meet in 2018 to produce reform recommendations for the 2019 Legislature.

The state’s current higher-ed model has a single board governing all 11 state institutions. But that model has been in place for 80 years, and America’s technological revolution means it’s time for a change, Burgum said in announcing the task force.

The Wizard of Oz

But as North Dakota sets off on the path to this Oz, it ought to remember the lesson learned by an earlier traveler on the Yellow Brick Road.

“If I ever go looking for my heart’s desire again, I won’t look any further than my own backyard,” says Dorothy (Judy Garland) at the end of the classic film.

That’s relevant, suggests Dennis Jones, president emeritus of the National Center for Higher Education Management Systems, a nonprofit that helps universities improve their management capabilities.

Remember, North Dakota already developed and implemented a nationally respected reform, Jones said. And it happened a lot more recently than 80 years ago.

The Roundtable Report on Higher Education dates back to the 1990s and won high praise across America for its model of “Flexibility plus accountability,” Jones said.

“That’s as good a governing philosophy as there is out there,” he said. “And it worked well for a decade,” until it stalled amid legislative

On Feb. 22, 2017, the Minnesota House and Senate met in a joint session to vote for new members of the University of Minnesota Board of Regents. The Minnesota Constitution enshrines the university’s autonomy and independence. IMAGE: UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA wrangling, challenges to the chancellor’s authority and other controversies.

But that was then. Why shouldn’t North Dakota try something new? North Dakota is free to do just that, Jones said. It simply should think hard before doing so.

“The Center has been involved in pretty much every major change in higher-education governance in America in the past 25 or 30 years,” Jones said.

“And one piece of advice that we consistently give is this: Don’t change the organizational structure until you’re convinced that nothing else will work.

“That’s because every time things change dramatically on the governance side, it takes five years to sort it out. And a lot of time, energy and money gets spent in trying to rebuild things that often could have been fixed in a much less costly and drastic way.”

1776

In 1972, the movie “1776” showed how the debates over our country’s founding still shape American life today.

In Minnesota, higher ed governance dates back to that state’s own founding. And we wouldn’t be surprised if those 1858 debates prove influential in modern North Dakota as well.

That’s because the Minnesota Constitution addresses a key problem that has dogged North Dakota: the challenge of governing community colleges, state colleges and high-level research institutions all under one roof.

Minnesota avoids this by running not one, but two higher-ed systems. The first governs the University of Minnesota, which is named in the constitution and given relative autonomy under a Board of Regents. The second governs everyone else.

A highlight of this system – and a testimony to higher ed’s importance in Minnesota – is the joint session of the Legislature that the state holds to elect regents. “The House and Senate basically meet as a committee of the whole, and every member gets one vote,” said Steve Kelley, senior fellow at the U of M’s Humphrey School of Public Affairs, and a former state senator who chaired the Senate Education Committee.

In North Dakota, a similar system likely would put the University of North Dakota and North Dakota State University under one board, and the nine remaining state institutions under another.

The Oregon Trail

But an even more intriguing reform might be found at the end of The Oregon Trail. No, not the 1959 movie of that name, but the actual trail, which led pioneers to Oregon.

For not only did Oregon reform its higher ed system as recently as 2012, but also the reform showcases an elegant answer to North Dakota’s most vexing higher-ed question: Who’s in charge, the chancellor or the presidents?

Here’s Oregon’s answer.

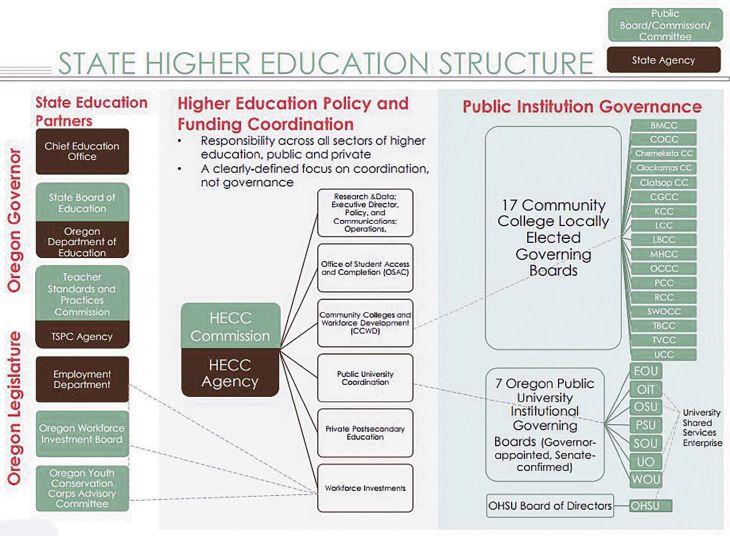

Oregon until the 2012 reforms had a single higher-ed board, much like North Dakota. Which brought about many of the same problems: “In particular, there was a real push by the University of Oregon and Portland State University for more autonomy,” said Ben Cannon, executive director of Oregon’s new Higher Education Coordinating Commission.

“But once that happens, how does a state system retain any systemlike properties?”

The answer is, by rendering unto the schools that which is the schools’, while keeping for the state that which is the state’s.

Oregon created a slew of new governing boards, one for each institution. Each board sets policy, hires and fires the president and manages admissions and other functions, no questions asked.

But the HECC – which replaced the Oregon State Board of Higher Education -- retains two key powers: First, the power over missions and programs; if an institution wants to open, say, a new law school, it must get the HECC’s permission.

And second, the power over budget relations with the Legislature. Oregon lawmakers typically appropriate higher-ed dollars in one lump sum. That money goes to the HECC, which then sends checks to each institution.

In this way, “our commission and our agency can focus exclusively on the policy and budget questions associated with reaching our higher education goals,” Cannon said.

“But we’re not managing the presidents. We’re not dealing with a controversy about a proposed new dorm. We’re not setting degree requirements or deciding on financial aid.

“That kind of thing can bog down a governing board, and at times, it occupied a big chunk of the agenda of the former state board. … (In contrast), the new system has been pretty smooth. It’s worked remarkably well.”

Star Wars: The Last Jedi

For the purposes of this story, “Star Wars: The Last Jedi” is an afterthought. It’s simply an acknowledgement that Doug Burgum, America’s most tech-savvy governor, may well push a space-age reform of his own.

Even then, Burgum should be mindful of one other core piece of advice, said Jones of the National Center for Higher Education Management Systems:

“Form follows function,” Jones said.

“North Dakota should talk about the functions first. What are you trying to get done? Which functions can go where?

“Then once you do that, you can ask, does the current system fit those functions, or does it not?”

Answering those questions -- and strongly considering the status quo as a potential answer – are prerequisites to successful reform, Jones suggested. PB

Tom Dennis EDITOR, PRAIRIE BUSINESS

TDENNIS@PRAIRIEBUSINESSMAGAZINE.COM

701 780-1276

In 2011, Oregon’s higher education reform efforts resulted in the creation of the Oregon Higher Education Coordinating Commission, a possible model for North Dakota.

IMAGE: HECC