5 minute read

The Value in Waste

Upper Midwest engineers, city officials and company managers work together on energy projects

BY LISA GIBSON

Dustin Hansen says he would absolutely recommend partnership projects like the one he helps maintain between the Sioux Falls, S.D., city landfill and the nearby Poet ethanol plant in Chancellor, S.D. As superintendent of the landfill, Hansen is crucial in an agreement that provides landfill gas (LFG) to Poet for $4 per mmbtu. The landfill makes 25 percent of its revenue through the partnership, keeping tipping costs low, and Poet displaces about 18 percent of its natural gas use.

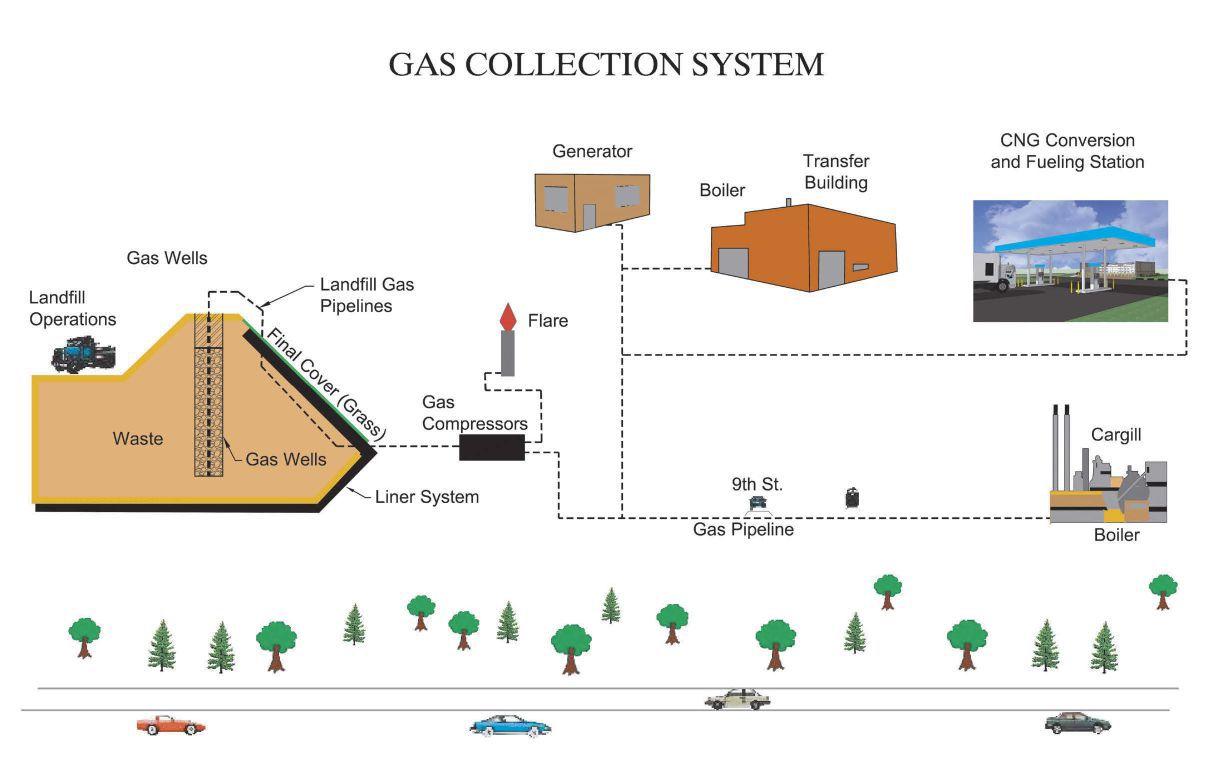

Similarly, the Fargo, N.D., landfill sells LFG to Cargill Inc., where it’s used in an oilseed processing facility. The arrangement solves the landfill’s odor problem and gives Cargill a cheap energy source, at $1 per mmbtu. Terry Ludlum, solid waste utility director for the city of Fargo, would recommend the collaboration to other landfills, too.

Hansen and Ludlum agree on the key to success: direct use for the LFG, as well as the around-the-clock operation of that direct user. “All of it is being collected and used,” Hansen says. “The only time the gas isn’t used is when the ethanol plant is down for maintenance. Last year, we operated 96 percent of the time.”

In Grand Rapids, Minn., it’s not LFG, but wastewater treatment effluent that brings the city savings in heating multiple facilities. “It’s a win-win,” says Jason Benson, a project manager for AE2S, the engineering firm working on the many facets of the systems. “It’s not only a big benefit for the city and a savings, but also the public utilities is doing their part and on the forefront of trying to provide green energy.”

A Unique Partnership

LFG production and leachate are problems for most, if not all, landfills and Sioux Falls was no exception when the city began to explore options for using its LFG a few years ago, Hansen says. Poet heard about the city’s intentions and approached it with the partnership idea.

The initial system was installed in 2008 and 2009, including collection wells that pool the gas, the LFG conditioning facility that removes moisture and pressurizes the gas, and the 11-mile pipeline to the ethanol plant. Once the LFG reaches the ethanol facility, it’s used in special burners that can handle the methane. Poet owns the rights to all the LFG produced at the landfill. “Once it gets to their boundary, they own it from there,” Hansen says.

Interestingly, the landfill covered the approximately $4.8 million bill, not only for its on-site infrastructure, but also the entire pipeline up to Poet’s location. It also owns and operates the pipeline. It did not pay for anything Poet installed on-site.

“Sioux Falls is pretty unique,” says Fred Doran, solid waste department manager for Burns & McDonnell engineering firm, which handles the Sioux Falls system, as well as many other waste-to-energy projects on the northern plains. In typical LFG projects, a third party operates and owns the pipeline or the two parties split that cost, he says. In this instance, the landfill accepted the risk and cost with the assurance of Poet’s longevity in its location, Doran says.

The project was installed using existing funds, Hansen says, including tipping fees set aside for special projects. And it paid for itself in 35 months, he says. It has been expanded almost every year and is now operating with 150 collection wells.

Doug Morris, solid waste coordinator for Crow Wing County, Minn., says the Sioux Falls-Poet partnership is the best-case scenario. “They did it right. They can expand their program without any cost to the taxpayers. That was a great win-win for those guys.”

Crow Wing’s landfill has a system that collects LFG to heat on-site facilities in the winter and provides revenue through carbon credits. Since the system began operation in 2009, the landfill has gained $325,000 in credits and has saved around $10,000 in heating bills. Crow Wing initially intended to sell its LFG to a lumber manufacturer, securing that crucial direct user, but the plant closed before the project was completed. “It would have been great for us because they operated

24/7. They’d use 100 percent of our gas.” Another option was using the LFG to produce electricity to sell to the grid, but the payback wasn’t good, Morris says.

“The benefit is using it in-house,” says Dean Frederickson, general manager of the Chancellor Poet plant. “If we were to produce electricity, we’d use that in-house, as well.”

The majority of the ethanol produced at the Chancellor plant is sold in California, which has strict rules on carbon intensity. The LFG lowers that intensity in Poet’s ethanol, making it attractive for that market, as well as qualifying Poet for the state’s green credits. The only limitation with the project is the amount of LFG available.

“The landfill is tapped out as far as LFG that can be produced,” Frederickson says. “And we could use more.”

Even with low natural gas prices, the system is a boon for both parties. “With the current energy market, it’s a bit harder to justify,” Hansen says. “But there are always ups and downs.”

Morris agrees. “Three years ago, it was a pretty good deal. It’s still a good deal, but it’s harder to make it. In another three years, we might have a user.”

‘In the Black’

In a more conventional agreement, Fargo and Cargill split the cost of the force main running the 1.5 miles between the landfill and the plant. Like the Sioux Falls system, each covered their own on-site costs for a total initial investment of about $1.3 million each, Ludlum says. Cargill is contracted to the amount of LFG produced by the 20 collection wells installed initially, but the landfill can send more from the multiple expansion wells, Ludlum says. The landfill also uses its LFG to heat on-site buildings and to run an electricity generator, selling power to the grid.

“We got our capital costs back,” Ludlum says. “So now we’re in the black on the project.”

The plant was built in 1990 in an area that was then rural. “Quickly, we got neighbors all around us. Some of the challenges with that are odor and blowing debris.” Flaring was studied as a solution but was not a good option.

The nearby Cargill plant approached the city with its proposal to buy the LFG at a price that would benefit Cargill and return the city’s capital investment. A 20-year contract was signed between the city of Fargo and Cargill in 2002, so negotiations for a new contract could begin in the next few years. The good working relationship and advantages to both parties make continuing the partnership a given, Ludlum says.

With greenhouse gas reduction a federal requirement, landfills without those systems to capture gas are investing in processes now. “There’s a very strong possibility we would have had to install a landfill gas collection system,” Ludlum says.

Wastewater Win

In Minnesota, public utilities also have been directed to lower their carbon footprint. The Grand Rapids Public Utilities Commission projects using wastewater effluent are significantly boosting that renewable component, says AE2S’s Jason Benson. The effluent from the wastewater treatment plant is passed through a heat exchanger to provide heat and cool air for the administration building on-site.

Another heat exchanger was installed at an industrial lift station that sits near the city’s library. The industrial waste, which averages about 130 degrees Fahrenheit, is used to heat the library, which is owned by the city and generates more savings.

The city also had a new force main project installed recently that conveniently sits near the YMCA. The heat exchanger there makes it possible to preheat water, as well as maintain comfortable temperatures in the pool and hot tub. Soon, the heat exchanger will also provide heat and cooling for the entire YMCA building, Benson adds.

AE2S also is working on a system in Williston, N.D., that will use wastewater treatment effluent to heat and cool its administrative building.

“There are opportunities to take a waste stream and utilize it for heat or cooling, or energy,” Benson says. “A lot of facilities that have digestion use biogas for energy, as well. It’s another source.” PB

Lisa Gibson Editor, Prairie Business 701.787.6753 lgibson@prairiebizmag.com