7 minute read

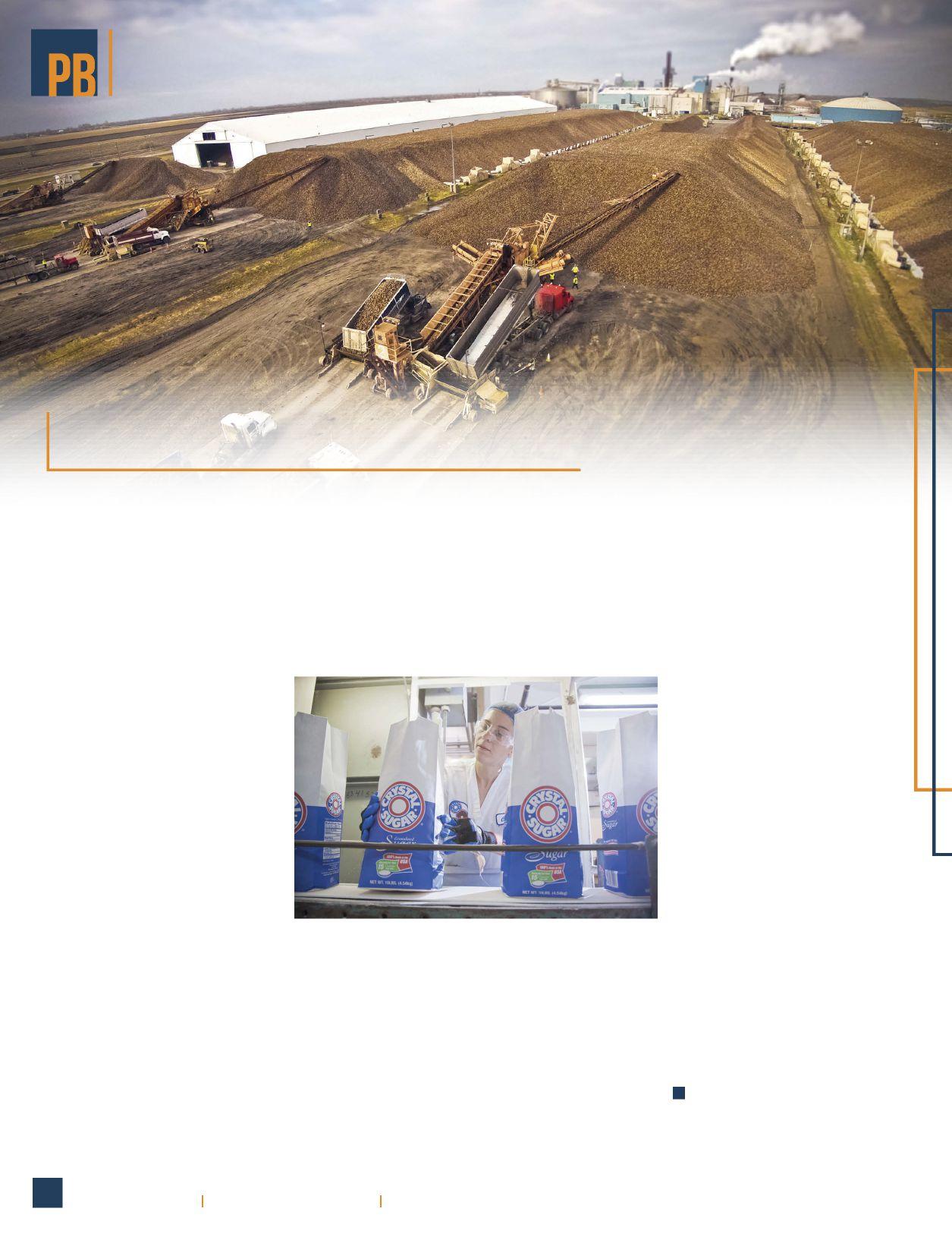

American Crystal Sugar

Direct economic impacts: $1.7 billion. Direct and secondary impacts: $4.9 billion.

Direct full-time employment: 2,473. Secondary full-time employment: 18,830.

That was the sugar beet industry in Minnesota and North Dakota in 2012. Which is why a team of North Dakota State University agricultural economists concluded the following:

“Although the sugar beet industry in Minnesota and North Dakota is not large in terms of acres or geographic area, the magnitude of key economic measures ... indicate that the industry contributes substantially to Minnesota and North Dakota economies.”

Substantially is right. As the numbers show, the sugar beet industry is central to the rural economies of the two states.

And American Crystal Sugar Co. in Moorhead, Minn., is central to the industry.

“American Crystal is the largest beet-sugar producer in the country,” said Lisa Borgen, vice president of administration at the cooperative.

“In the United States, 40 percent of all of the sugar that’s consumed is beet sugar. We produce 39 percent of all of the beet sugar, and 20 percent of all of the overall sugar production.”

And there’s more.

“On Oct. 1st, when we move the beets from the field to the piles, we start the most concentrated movement of a crop anywhere in the world,” Borgen said.

“The window is narrow, and the amount of crop that we have to bring in is huge.”

Local newspapers chronicle the migration, warning drivers to steer clear of the beet trucks and to watch for roads made slippery by spilled beets.

“There are about 12 million tons of beets that get piled,” Borgen said.

“During the harvest, there are 9 million farm truck miles that are driven, and it also takes about 10,000 extra people to move those beets. Isn’t that something?”

American Crystal is a cooperative, which means it’s owned by 700 grower/shareholders. The company employs about 2,000 people and runs six factories, five in the Red River Valley and one in Sidney, Mont.

“A couple of things stand out about American Crystal,” Borgen said.

“First, ours in an American-made product, and the people who grow it and who work in our factories are all really proud to be part of something that is made in America.

“Second, we’re always conscious of the financial impact we have up and down the valley.” It’s rewarding not only to create jobs, but also to help farmers stay on the land and pass the legacy of farming down to their children, she said.

Third, the technical skills needed to work in the factories continue to grow, which is why American Crystal has extensive training programs to help workers advance.

And fourth, “there’s pride that this is a process in which we start with tiny seeds, and we turn those eventually into 3 billion pounds of sugar. It’s just really amazing.” PB

By Tom Dennis

GRAND FORKS, N.D. – When you’re talking about hospital architecture, there are a few words you don’t expect to hear.

One of them is “Disney.”

But when Prairie Business separately interviewed three architects who work for three different firms and are designing three different hospitals in our region, that word came up all three times. Interestingly, so did several other key words. For in the interviews, common themes emerged; and in this story, our hope is that by describing those themes, we can help residents understand what to look for as their new hospitals take shape.

Competition

We’ll get to the word “Disney” in a minute. But first, let’s focus on a word that helps explain why so many hospitals are being planned or built at the same time: competition.

No, competition isn’t the only reason why the metro areas of Grand Forks, Fargo, Minot, Sioux Falls, Rapid City and Duluth, as well as smaller communities such as Grafton, N.D., and Cooperstown, N.D., all will see or recently have seen multi-million dollar hospital projects. (The projects range from a proposed $26.2 million Cooperstown Medical Building to Essentia Health’s $800 million plan to revamp its medical campus in Duluth, one of the biggest medical expansion projects in Minnesota history.)

Coincidence helps explain the timing, too. In most of these communities, the hospitals date back decades, and the changes in modern medicine simply mean that many buildings are near the end of their useful life.

In Minot, for example, “the hospital operates out of two primary buildings, and one of them is approaching 100 years old,” said Kyle Wilson, partner at TEG Architects in Jeffersonville, Ind. TEG is the architect of record for Trinity Health’s plan to build a new, $275 million hospital in Minot.

“So for example, the ceiling heights are very low, and the rooms are semiprivate, which means you have two beds in every room. And the size of those rooms is probably smaller than what you’d want in a private room today.”

In the new Trinity Health hospital, all of the rooms will be private – including the rooms for infants in neonatal intensive care. (Twins, triplets and quadruplets will be cared for with their siblings in rooms with multiple bassinets.)

But competition does help explain why single rooms and other amenities have become the standard, Wilson said.

“On the patient side, you have choices on where your health care is delivered,” he said.

“Trinity Health wants to be the provider of choice. They want to be at the forefront of your mind, so there’s definitely a focus on patient satisfaction and staff satisfaction.”

Jason Nordling, a principal at BWBR Architects in St. Paul, Minn. agreed. And don’t miss the fact that “staff satisfaction” is listed right alongside “patient satisfaction” as a competitive force, Nordling said.

BWBR is the architect of record for Avera on Louise, Avera Health’s 82-acre, $174 million campus that’ll be the largest building project in Sioux Falls’ history. And throughout the campus, Avera will be taking care to make the staff areas attractive as well as functional, with an eye to boosting recruiting and retention.

“Fifty years ago, staff made a space work,” Nordling said.

“Today, we’re making workable spaces for the staff. We have people who do workplace design, and they’re designing collaborative and flexible staff spaces that include artwork, views of nature and other elements that are as important to staff as they are to patients.”

On stage, off stage

Speaking of staff, that brings us back to the Disney influence. Because one of the biggest differences between older and newer hospitals is the lesson of Disney World: the careful separation in new hospitals of the customers and staffers’ worlds.

“It’s called the ‘on stage’ and ‘off stage’ model,” said Todd Medd, healthcare practice studio leader at JLG Architects of Grand Forks, N.D., the company that’s the architect of record on Altru Health System’s $305 million hospital project in Grand Forks.

“On stage is where the patient is, and it starts from when the patients and visitors arrive on site. They’ll encounter a very calming, hospitalitybased environment, and that will continue into the elevators and up to their rooms.”

Meanwhile, physicians, nurses and other providers will use hallways, elevators and even entrances to patients’ rooms of their own.

“All of those back-of-house functions,” said Wilson of TEG, “such as your maintenance, your kitchen, your biomedical department, your materials management – those functions that are so essential for a hospital – the patient won’t see.

“Again, it’s the Disney concept where you’re just trying to hide some of the support functions so you can focus on the hospitality side.”

Understand, there are evidence-based health reasons for this change, said BWBR’s Nordling. By keeping the hustle-and-bustle “off stage” and the patient areas serene, patients will sleep better and be much less stressed. In any recovery process, that helps.

And consider: Once staff step into their own area, they’ll be much freer to collaborate and converse. For example, no longer will staff have to stop talking about a case when a patient enters an elevator, because the staff will be traveling on elevators of their own.

Three zones

Let’s take a closer look at a patient’s room – the one that may have separate entrances for patients and staff.

That room is likely to have three zones, the architects agreed.

Near a door will be the caregivers’ zone, where nurses and other employees may find a workstation and supplies.

The patient’s zone will be in and around the bed. The smart bed, that is, the Star Trek-like wonder that will be monitoring the patient. But that’s another story.

Then there’ll be the family zone, which may be equipped with not only chairs, but also a sleeper sofa where family members can stay.

Comfort and hospitality are the keys.

Infection control

So is infection control, the architects said. “All of the finishes are being designed with that in mind,” Nordling said.

“So, they’re coming up with newer, better and quieter flooring that’s easier to clean, for example. And scrubbable ceilings that still have a high noise-reduction coefficient – things like that.”

Other infection-control elements will include anti-microbial coatings, seamless (and therefore easier to clean) sinks, automated bedpan washers and hands-free controls.

But does hospital architecture routinely specify that level of detail?

“I would describe it as excruciating detail, right down to the type of handle that’s on the door and the color of lighting that’s in the space,” Nordling said.

“We’re a firm that provides both architecture and interior design. So if you can see it, it was probably planned intentionally by the design team.”

Community wellness

One other big theme that emerged from the interviews is wellness. And not just patient wellness.

Brad Wehe is Altru Health System’s COO and will become CEO in January. When Altru envisions its remade campus in Grand Forks, “we’ve talked about this whole new era, because it’s so much more than a building,” he said.

It’s also the surrounding property. “Our decision to stay on that campus was really to create a ‘hospital in a park,’” he said.

“We want to be proactive with prevention and healing, not only inside the facility but also outside.”

So, if you as a visitor turn into the new Altru campus in years to come, “you’ll see trees and water and greenspace, and the building will incorporate sunlight and glass, so that you can be inside getting healed from the outside, and outside looking in and getting healed from the inside.

“Here’s what you won’t see: a huge facility that’s intimidating and is surrounded by parking lots,” he said.

In other words, hospital architecture these days includes landscape architecture, and that means trees, bike trails, gardens and walking paths that meander along nearby creeks.

As Nordling of BWBR explained, “the Avera on Louise campus will go beyond the idea that it’s there for sick people. It’s there for community wellness.

“And as a result, everything you’ll see will be built around the idea of being well rather than treating an illness.”

The goal is for people to use the campus not only when they need medical care, but also when they’re healthy – and are biking and walking to stay that way. PB

TOM DENNIS EDITOR, PRAIRIE BUSINESS TDENNIS@PRAIRIEBUSINESSMAGAZINE.COM 701.780.1276