8 minute read

SAILING SMART

The Atlantic Ocean Conveyor

What Does It Mean As We Head South?

Advertisement

by Bill Biewenga

Understanding global ocean currents is important for all offshore sailors, but it’s especially important for multihull sailors. Strong wind against currents offshore in places like the Gulf Stream can quickly create wickedly steep and breaking seas. Those sharp seas can certainly be problematic for monohull sailors, but for multihulls and those onboard, they can be catastrophic leading to pitch-poling conditions. Regardless of the type of vessel or even if someone is land-bound, ocean currents play a significant role in all of our lives and largely determine how the planet holds, dissipates and distributes heat. Global warming is quickly being accepted as reality rather than as theory. Even the Wall Street Journal has reported that the Greenland icecap is melting faster than previously expected. One of the possible outcomes of global warming and melting of the glaciers and ice on and around Greenland and the Arctic is that the Gulf Stream’s flow could be altered. How does all of that fit together

and seem to make any sense? How soon and in what way will any of this affect those of us who sail boats to the Caribbean or across the Atlantic? Is the sky really falling? It may not be falling, but it does seem to be heading towards a tipping point.

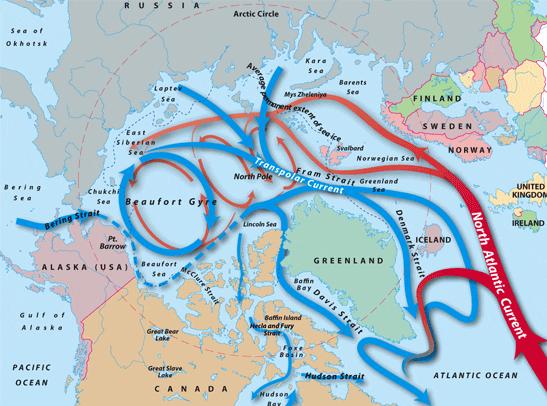

THREE DIMENTIONAL OCEAN CURRENTS

To understand what’s happening to the earth’s climate, we also need to understand how the ocean’s currents move water around the planet. It’s not just water that’s being moved, it’s also heat and varying salinity that’s being circulated. Most of us are familiar with the Gulf Stream, that great current of warm water that flows between Florida and the Bahamas and meanders in a northnortheasterly and northeasterly direction toward England and northern Europe. As huge as it is, the Gulf Stream is only one small part of the global water circulation known as The Global Thermohaline Circulation or The Ocean Conveyor. (See: http://www.whoi.edu/oceanus/ viewArticle.do?id=9206§ionid=1000)

The Gulf Stream is a warm surface current, but to more fully understand the complete circulation, we need to think in 3-D. There are deep currents as well. When combined with surface currents we begin to understand The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (MOC). Warm, salty water flows northward from the tropics in the Atlantic. As the water gets further north, approaching the Faroe Islands the water cools and sinks, releasing its heat energy to warm northern Europe. The water then flows back toward the south, deep beneath the surface water. The sinking water draws more warm water from the south at the surface, creating a “demand” for the Gulf Stream water. The Gulf Stream is, in a sense, “pulled” toward Europe by the sinking action of the now-cold water. The system isn’t just about warm and

cold, surface and deep currents, though. Salinity plays a role in determining the overall flow of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, as well. As sea ice forms, salt is released. The cold water sinks to a level that is just below the ice, protecting the sea ice from thawing by the warmer, saltier (and hence denser) water that lies further down.

As glaciers and sea ice melt, and as rivers increase their flow of fresh water into the Arctic and Hudson’s Bay, more of that cold, less dense water remains on top of the ocean. That could potentially block the warmer water below from releasing its heat and interrupt the flow of the Gulf Stream at the surface. (See: http://www.whoi.edu/oceanus/ viewArticle.do?id=9209§ionid=1000) Researchers have found evidence of this occurring in the past and leading to significant climate change. Some of the researchers believe that the earth could become significantly warmer on a global scale while some regions, such as Europe could become colder due to alterations in the Global Thermohaline Circulation. More glacial melt in Greenland or Arctic sea ice or increased freshwater flow through “gates” in the N. Atlantic can and have altered the Gulf Stream flow according to paleoclimatologists. Wouldn’t it be a good idea to monitor the freshwater flow rates coming through those regions? Gary Comer, founder of Land’s End, presumably thought so, and provided Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (WHOI) with a grant to help fund some of the cutting-edge research.

ADDING FRESHWATER NORTH OF THE GULF STREAM: IMPLICATIONS

“It certainly makes sense to continue monitoring ocean, ice, and atmospheric changes closely,” Ruth Curry of WHOI said. “Given the projected 21st century rise in greenhouse gas concentrations and increased freshwater input to the high latitude ocean, we cannot rule out a significant slowing of the Atlantic conveyor in the next 100 years. I emphasize that we are talking about

century timescales to witness measurable changes in the ocean transports of mass and heat across the GreenlandScotland Ridge-we are not suggesting that the Gulf Stream will shut down.” Findings are not conclusive, and researchers’ opinions vary, but there’s new evidence of higher temperatures that could mean accelerated change. Scientists have found indications that tropical Atlantic temperatures may have reached 107°F millions of years ago —about 25°F higher than today. At that time, carbon dioxide levels in Earth’s atmosphere were high, the scientists said. It’s possible that future ocean warming from the buildup of heat-trapping carbon dioxide may be much greater than predicted by computer models now in use. “These temperatures are off the charts from what we’ve seen before,” Karen Bice, a paleoclimatologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. “If the models are not right, society is not well informed or well served.”

According to an unpublished survey by Potsdam University researchers Kirsten Zickfeld and Anders Levermann, expert scientific opinion varies greatly on the likelihood that excess freshwater runoff from the Arctic will alter the North Atlantic conveyor belt in this century. Some scientists consulted for the survey said there is no chance that the current will break down. Others estimated that the chance of a complete shutdown is greater than 50 percent if global warming climbs by 7.2° to 9° Fahrenheit (4° to 5° Celsius) by 2100. Stefan Rahmstorf, a professor of ocean physics at Potsdam University in Germany, believes the chance of a circulation shutdown could be as high as 30 percent. He said any possibility of such a scenario, even if slight, is cause for concern. “Nobody would accept expanding nuclear power if there was a 5 percent risk of a major accident,” he said. “Why would we accept expanding oil and coal power if there is a 5 percent risk of a major climate accident?”

MONITORING THE ATLANTIC CONVEYOR

The reality seems to be that while there is agreement that the climate is warming

on a global scale, there is little consensus on what that implies over a 100-year term. Some of the possible outcomes could be positive (i.e.: shipping could travel directly through the Northwest Passage much of the year, fishing could be more accessible in the Arctic, and so forth).

Many of the outcomes could be negative or even catastrophic: entire species could be wiped out, crops in certain regions could fail causing widespread famine, and indigenous peoples could have their lives uprooted. No one seems to imply that such a scenario will take place in the next decade, but once the process hits a tipping point, it may take decades to slow the process that may or may not be irreversible over the next 100 years.

Monitoring the speed, temperature and salinity of the Ocean Conveyor will help us to better understand the rate of change in the climate. (see: http://news. bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/4485840. stm) Tom Rossby, an oceanographer at the Graduate School of Oceanography at the University of Rhode Island says, “While the above scenario is conceptually simple, it is by no means clear whether and how such a shutdown might take place, indeed whether the supply of fresh water is large enough and can be delivered to the right place to cause a significant change. We can speculate about these things as much as we like, but in order to establish some certainty to these concerns, it would help to have an early warning system, some means of detecting a possible change or decrease in the strength of flow of warm waters into the Nordic Seas.” Rossby likens the waters around the Faroes to a canary in a coal mine. “If any decrease in inflow into the Nordic Seas were to develop, the waters around the Faroes will be the ones to watch for such change.”

From my own personal anecdotal experience, ocean temperatures have appeared to generally rise over the past decade or more. Sea ice in the Arctic Ocean has continued to shrink, and there are increasing thoughts that the North Atlantic Conveyor system may be at a tipping point. (See: https:// www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2019/12/why-ocean-current-critical-to-world-weather-losing-steam-arctic/) Surface currents have continued much as before, but that’s not to say it’ll always remain so. NASA is already noting changes in surface currents. (See: https://climate.nasa.gov/news/2950/

arctic-ice-melt-is-changing-oceancurrents/) Of course, some years are stormier than others, and, as always, it’s best to remain informed as you get ready to head south for the winter. As I write this article, we are already seeing an early start to what appears to be an actively stormy year. Regardless of what you may personally think of global climate change, vigilance to help make informed decisions is always a good idea – especially during hurricane season.

Bill Biewenga has sailed some 400,000 miles offshore and works as a moderator for Safety at Sea Seminars, BWS columnist and offshore delivery skipper.

Audio: NPR interviews Ruth Curry, from Woods Hole: https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=4706667?storyId=4706667

National Geographic: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2019/12/ why-ocean-current-critical-to-world-weather-losing-steam-arctic/

Woods Hole Oceanographic: https://www.whoi.edu/know-your-ocean/ocean-topics/ ocean-circulation/the-ocean-conveyor/

NASA: https://climate.nasa.gov/news/2950/arctic-ice-melt-is-changing-ocean-currents/