11 minute read

Desert View Inter-tribal Cultural Heritage Site: Connecting Visitors to Grand Canyon’s Tribes

By Julie Hammonds

So says Stewart Koyiyumptewa, tribal historic preservation officer for the Hopi Tribe.

So say the members of 11 American Indian tribes that feel deep and ancient connections to lands and waters now within Grand Canyon National Park. For more than 12,000 years, people have lived on what are now park lands, gathering food, telling stories about those places, waters, and animals, and weaving a history and a livelihood.

These tribes include the Havasupai Tribe, the Hopi Tribe, the Hualapai Tribe, the Kaibab Band of Paiute Indians, the Las Vegas Band of Paiute Indians, the Moapa Band of Paiute Indians, the Navajo Nation, the Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah, the San Juan Southern Paiute, the Pueblo of Zuni, and the Yavapai-Apache Nation—tribes that still exist today, and still feel the canyon’s powerful pull.

An Ancient Connection is Tested – Several of these tribes connect their origin to Grand Canyon. Among these are the Hopi. “Our people believe we emerged from the Grand Canyon, and after we’ve completed our life on earth, we go back to the Grand Canyon,” Koyiyumptewa says. “It’s a place of high reverence to the Hopi people.”

Once the national park was established in 1919, the railroad and Fred Harvey’s hospitality company brought tourists to the South Rim to view what looked, to many, like a geological wonder or a divine miracle—but not a home. Many visitors couldn’t believe anyone had ever lived or traveled in that vastness. Even today, some visitors still imagine there are no more American Indians.

But things are changing: a way is opening up for tribes to reaffirm their connection to the canyon, in their own lives and in the minds of the park’s six million annual visitors. These tribes are working with the National Park Service and other partners to bring a new endeavor to life: a Desert View Inter-tribal Cultural Heritage Site. A Timeless Watchtower Rises – After the national park was established, tribal people sometimes felt cut off from crucial pieces of their cultural life. They had lost lands and traditional access rights, and had difficulty working with the government to find ways they could still live on their land or use animals, plants, or other park resources.

But even then, someone was striving to maintain a connection between the federally managed park and the tribes: architect and designer Mary Colter, the Harvey Company’s chief architect and designer from 1910 to 1948.

Colter was profoundly influenced by American Indian art and architecture. Her Desert View Watchtower near the park’s eastern entrance, which opened in 1933, evokes the architecture of the Ancestral Puebloan peoples of the Colorado Plateau. Built of native stone, it’s 70 feet tall. Inside, four stories are connected by staircases that curve upward to spectacular 360-degree views of the eastern Grand Canyon, the Colorado River, and the Painted Desert. Colter selected Hopi artist Fred Kabotie to create some of the memorable murals inside—recently conserved by a team that included Kabotie’s grandson Ed.

“It’s pretty stunning, what they created, and why,” says Jan Balsom, senior advisor for stewardship and tribal programs at Grand Canyon National Park. “It was to introduce the visiting public to the area’s indigenous peoples. The Watchtower was designed to emulate the cultures and buildings Mary Colter had been studying.”

What was originally created to introduce visitors to the Southwest’s diverse and rich cultural heritage is undergoing a transformation very much in keeping with its origins. The Desert View site is becoming an “inter-tribal cultural heritage site”—the first in the National Park Service. Mae Franklin, former Navajo tribal liaison to the Kaibab National Forest and Grand Canyon National Park, calls the project “an opportunity to tell our stories and showcase our tribes. The goal is to educate the world community that tribes are still here, we are part of the fabric of our communities, and we have our unique ways of thinking and abilities to think about the land.”

Photo by John Dillon

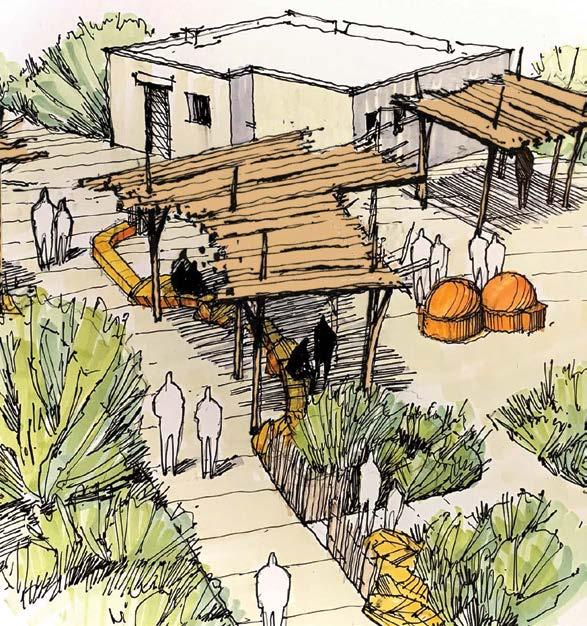

Tribes and the National Park Work Together – Desert View was designed as the traditional scenic overlook one might find at any large national park, its signature feature being Colter’s Watchtower. As plans for the cultural heritage site are implemented, the space will offer multiple opportunities for first-voice cultural interpretation from associated American Indian tribes (including cultural demonstrations, which have already begun). Over time, the site will enhance visitor understanding and appreciation of the cultural significance of Desert View and Grand Canyon National Park as a whole and showcase tourism opportunities on surrounding tribal lands.

Significantly, it will give tribal members meaningful opportunities to connect with the canyon, the national park, and its visitors.

“It’s an opportunity to show park visitors a true reflection of who we are,” says Koyiyumptewa. “And then maybe to steer some of those visitors to our own reservations so people can see for themselves that our peoples and cultures are still alive and well.” “Right now, the South Rim is the number one destination at Grand Canyon, but I hope Desert View will become that someday,” says Koyiyumptewa.

Zuni artist Ronnie Cachini at work in his studio in Zuni, NM.

Tribal Ideas Guide Design – The team developing this project comprises the tribes traditionally associated with Grand Canyon, the National Park Service/Grand Canyon National Park, Grand Canyon Conservancy, the American Indian Alaska Native Tourism Association (AIANTA), the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and park concessionaires. This group works with a design team led by artist and designer Andy Dufford.

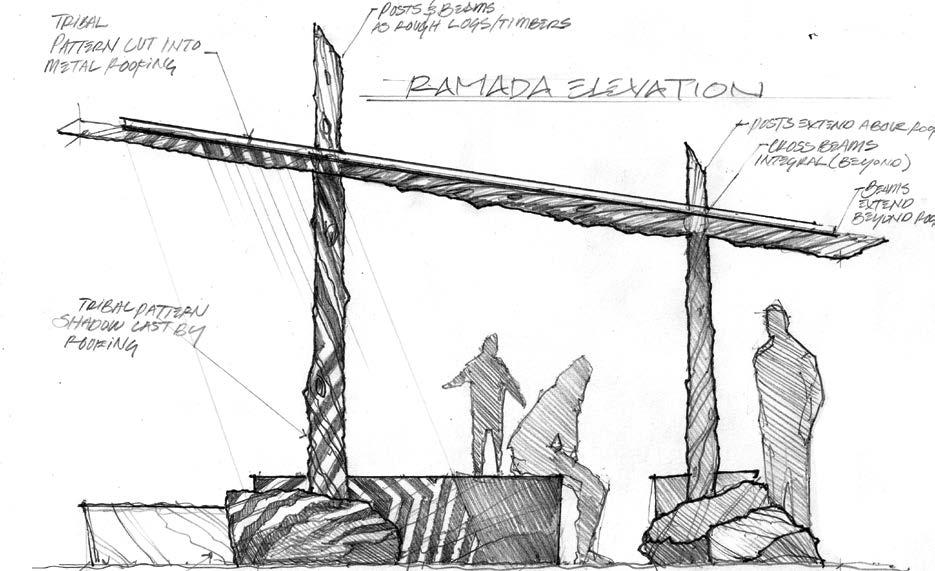

“Our process with the tribes has been twofold,” Dufford says. “One piece is about developing site elements that serve to share tribal heritage.” At every step, the tribes are shaping these design plans, which are due to become final this year. The second design piece is “making sure Desert View has a distinctly tribal feel and is different from all other overlooks.” Dufford calls the inter-tribal cultural heritage site “a unique opportunity to use the charisma of the canyon to interest visitors in a much broader topic, which is these amazing cultures that have inhabited canyon lands from time immemorial.”

The design team’s ideas are based on the relationship tribes have with the land. “Traditional tribal artists create with the materials at hand, so their work is shaped by nature,” says Dufford. “Because of their exquisite powers of observation and deep talent as makers, they come up with designs that are simple but incredibly rich. There is a continuity of people, places, and things that all work together with the environment.”

Visitors can expect changes to the parking and walkways to sequence arrival so when you pull in, you can see the canyon, much as it was originally designed in the 1930s. “Visitors will have a sense of arrival and where they’re destined to be,” says Balsom. Also, with financial support from Grand Canyon Conservancy, the design team is collecting an image from each tribe for transfer to the site in some permanent form, most likely stone.

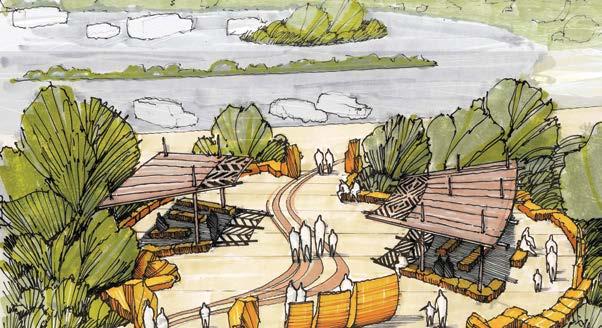

Concept renderings of the site, designed by Andy Dufford

A Cultural Heritage Site Takes Shape – When the National Park Service took over management of the Watchtower in 2015, the inter-tribal working group and park superintendent at the time, David Uberuaga, started to consider whether and how to use the area to benefit tribes. Some of the first tasks were the conservation of Kabotie’s murals, the establishment of a cultural demonstration program, and the development of internships and projects throughout the park for tribal youth.

The next phase will rearrange the site to give visitors an instant sense that this place is something different. A new orientation area will answer the questions “What is an inter-tribal cultural heritage site?” and “What tribes are traditionally associated with Grand Canyon?” A demonstration site will be added, access for people with disabilities will improve, and the amphitheater will be reoriented to showcase the view upriver. As the site becomes established, more cultural demonstration areas could be built for the making of baskets, rugs, or other items, and for activities such as bread-baking or agave-roasting. An existing building will become a tribal welcome center, providing exhibits and encouraging visitation to tribal lands.

Giving visitors a unique experience is only one aspect of the project. In discussions with tribal representatives, Vicky Stinson, National Park Service project manager for Desert View, has noticed that “they’re excited about bringing their families and other tribal members to the site, not only to see things regarding their own heritage but also to learn about other tribes’ heritages. They see this cultural heritage site as a place for themselves.”

“We share Desert View as a symbol to bond the peoples of yesterday, today, and tomorrow. The Watchtower serves as a connection to embrace the heartbeats of our people and visitors far and wide with the heartbeat of the Canyon.

We are still here.”

(Inter-tribal Working Group Vision Statement)

Demonstrators Connect With Visitors – The new cultural demonstration program is already connecting tribal members and visitors. Brian Gatlin, the ranger in charge of interpretive programming at Desert View, explains its impact through the story of Zuni jeweler Otto Lucio:

“Otto had all of his various raw materials on display while he meticulously forged them into finished pieces,” Gatlin recalls. “One young visitor was completely captivated by the beauty of the stones Otto was using. Otto gave the youngster his full attention, describing each type of stone and its origin, and the boy looked on, listening in wonder and awe. When he finished, Otto handed the boy three small pieces of turquoise, for the boy and his two sisters. The excitement and gratitude in the boy’s eyes was touching. It made me wonder what impact these conversations and interactions may have on people’s lives long after their visit.”

Demonstrators like Lucio can sell their work. “Our rough estimate is that the program has resulted in $500,000 to $750,000 in direct input into native artist communities,” Gatlin says. Other types of demonstrations may not have a commercial aspect, but all demonstrators receive a daily stipend, assistance with travel costs, and local housing, thanks to financial support from Grand Canyon Conservancy.

“While the financial upside is certainly a welcome aspect of the program, the chance to share their culture with visitors, as well as the opportunity to spend time at Grand Canyon, has been even more important to the participants,” Gatlin reflects. Tribal Tourism Grows – Navajo tribe member Franklin is one of many tribal representatives who see how this project could generate income for tribal members, through the demonstration program and by inviting Grand Canyon visitors to explore tribal lands. “The national park is the hub of northern Arizona tourism,” she says. “If we want to encourage people to come to tribal lands, that would be the place to do it. The key is to ensure the tribes are ready to welcome those travelers.

“Unlike other communities, my community of Cameron already has tourism, as the east gateway to Grand Canyon National Park. But we’re evolving, learning, and building capacity to benefit from it. We’ve never had this opportunity to speak to global travelers before,” she says. “We’ve been fortunate to be given this platform to say we are still here, and we continue to live our lives and be involved.”

Koyiyumptewa is also excited about economic opportunities for tribes as a result of the inter-tribal cultural heritage site. He calls it “a project that will be a foundation for other parks to follow once they see how successful partnering and collaborating with native tribes can be.”

“Our tribal colleagues are starting to take ownership at Desert View,” says Balsom. “That’s what we need to happen— that’s how it will succeed.”

Grand Canyon Conservancy provides key support for development of the inter-tribal cultural heritage site, funding the cultural demonstration program and attending meetings of the inter-tribal working group.

According to CEO Theresa McMullan, “These meetings are about listening to tribal members to see what they need for the site to make it an authentic experience, for visitors and for their own tribal members.”

GCC’s assistance via direct donations and in leveraging government grants has been crucial. Going forward, McMullan wants the Conservancy to support development of a business plan that will help determine not only how the site is used and shared, but what opportunities exist to bring economic development to tribal lands through tourism.

“A business plan is really important, because some tribes can provide tourism infrastructure for visitors immediately, some have to develop that capacity, and some may not even want to go there,” McMullan says.

“Desert View is one of our most important projects right now because it’s such a high priority for Grand Canyon National Park and for the National Park Service in general. This project can set the stage for how parks work with tribal representatives and tribal members, showing the whole nation how that can be done.”

If you’d like to contribute to this important project, call Danielle Segura, Chief Philanthropy Officer, at (909) 771-8737 or e-mail her at dsegura@grandcanyon.org.