3 minute read

THE FASTER LANE / TYLER BRÛLÉ

If you’ve been tuning in to various exchanges on Monocle 24’s flagship news programmes – The Globalist and The Briefing – over the past week, you might have noticed that we’ve been spending quite a bit of time comparing and contrasting how various governments have been handling their communications during this pandemic.

Well before 10 Downing Street thought that they were doing a good job bamboozling the world by saying very little, while saying everything when Boris Johnson was taken to hospital a week ago for “routine tests” (we’ll come back this topic shortly), we’ve been monitoring the shenanigans in the White House Rose Garden, the narrative coming from Vienna, slow-motion confusion from Shinzo Abe in Tokyo and a lack of urgency in Ottawa.

Advertisement

Now you might well be asking, “Why do communications matter in these times, when we should be more concerned with protective medical clothing, fatigued nurses and more testing?” (Though I sincerely hope that you’re not.) To be clear: without effective leadership, coherent collateral and sharp comms, it’s difficult to have much faith in the system. Allow me to illustrate. The World Health Organization (WHO) has been getting a rough ride – across a variety of fronts. Putting politics, China, Taiwan and some flip-flopping aside, how do you feel when you see the organisation’s top team before the cameras? Do they command respect? Are you following what they’re saying? Or are you distracted by the light-blue backdrop that’s fraying and fading at the edges? Is the wonky camerawork a bit of a distraction?

While we’re told that the WHO is woefully underfunded, and it might be argued that it’s the content of what’s being said rather than how it’s being presented that counts, I disagree. If the WHO had a dynamic director general and a couple of deputies who could own network airtime and onpage column inches, things might be different.

But they’re lacking dynamic leadership. As a banker friend

WHO SAID IT BEST

suggested, “It seems as though their media team has been having a good old expat lifestyle in Geneva and weren’t geared up for delivering on the ‘W’ part of their name.” At the other end of the spectrum you have the Danes and Swiss, who have demonstrated how to behave and communicate in a crisis – on camera, online and on the streets.

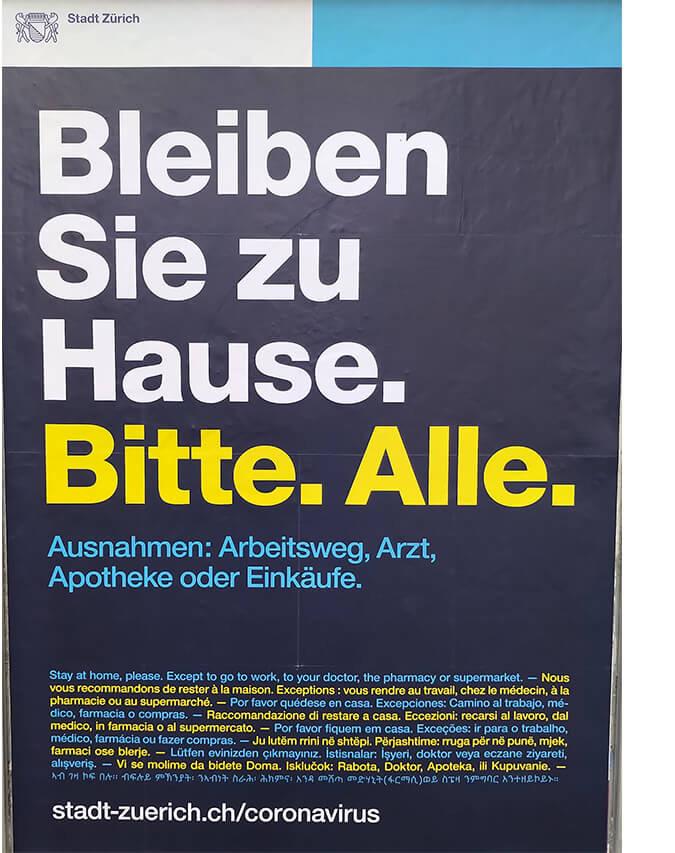

The Danish prime minister’s press conferences are tight, spare affairs – she’s front and centre and there are two to three regulars around her, max. The staging is authoritative, the graphics clear and there’s nowhere for the eye to wander. It’s all confidence and message. Down the street in Bern it’s been the same: crisp backdrop, short scripts, zero fluff and politicking, and trust ratings that are top of the charts. All of this is backed by a succinct awareness-anddirectives campaign that’s balanced by considerable social responsibility. For sure, the posters that have been released by the city of Zürich (pictured) will one day be demanding steep sums at design galleries around the world.

Which brings us back to Downing Street and its shameful approach to managing communications. Did anyone really believe that Boris Johnson went in for routine tests on a Sunday evening? Was it not a concern, when revealed during the daily presser, that his newly anointed deputy hadn’t spoken to him in three days? Were we not all speculating that things must have been far worse when we didn’t hear a peep beyond the endless loop of him being “in good spirits”. In another column we’ll get round to asking why the prime minister of one of Europe’s biggest economies doesn’t have a dedicated RAF medical team assigned to him. Or why there’s been such a need to communicate that he’s resting in a ward rather than a private room.

In semesters to come, PR, comms and journalism programmes will be looking for benchmarks that offer solid examples of how to manage public messaging in challenging times. Anyone for a field trip to Bern or Copenhagen?