2 minute read

Preserving Gardens in America

The founding impulse of the Garden Conservancy was preservation—the need for, and belief in, the possibility of garden preservation. The notion of preserving a private garden was foreign to Americans, even to most American gardeners, although there were certainly very well-known examples abroad—think Great Dixter, the Villa Gamberaia, or Vaux-le-Vicomte.

Certain American gardens, both public and private, had indeed been preserved by 1988, when Frank Cabot, with encouragement from his wife, Anne Perkins Cabot, decided to create the Garden Conservancy. Cabot, a dedicated and brilliant plantsman, was inspired by what he feared might be the imminent demise of an unusual garden in Walnut Creek, CA. For the most part, however, garden preservation came as a collateral effort to architectural preservation. In saving a great house, like Monticello, Vizcaya, or San Simeon, the garden was part of the package, rather than the central focus of the preservation efforts.

Advertisement

Why gardens came as late arrivals to the conversations around preserving other examples of American culture deserves further investigation and study. I believe part of the answer lies in the relative “newness” of this nation. As a culture, we are still too eager to obliterate examples of our history in favor of “the new.” The idea of preserving gardens has also suffered because of the notion that gardens might be fundamentally ephemeral and that ornamental gardens, and the act of gardening itself, might even be frivolous. This was especially true in a post-WWII American culture that wholly embraced the lawn and that may have seen large gardens as belonging to an old world order. We also have to come to terms with the strong possibility that misogyny may have played a part in the dismissal of the cultural importance of gardens, as in this country gardens (correctly or not) were often seen as the realm of women. There was a perception that men built houses and women created gardens around them. Thankfully, however, some gardens survived, though many significant ones remained at risk. Frank Cabot and a core group of his friends, many of whom were the same women who created and sustained the Garden Club of America, were important visionaries. This interconnected national community of gardeners knew that gardens were underappreciated as cultural objects and that garden design had, for too long, been overlooked as a significant art form. They saw that the stories these gardens told contributed significantly to the history of the nation and that gardens deserved to be understood and appreciated in their own right. Indeed, America’s gardens, as our mission statement now asserts, must be “preserved, shared, and celebrated.”

I believe wholeheartedly that America is entering a new “golden age” of gardening. Gardens can be agents of positive change—for individuals, as well as for communities as a whole. Since its founding in 1989, the Conservancy’s preservation work has led the way, and will continue to do so, in both deed and word.

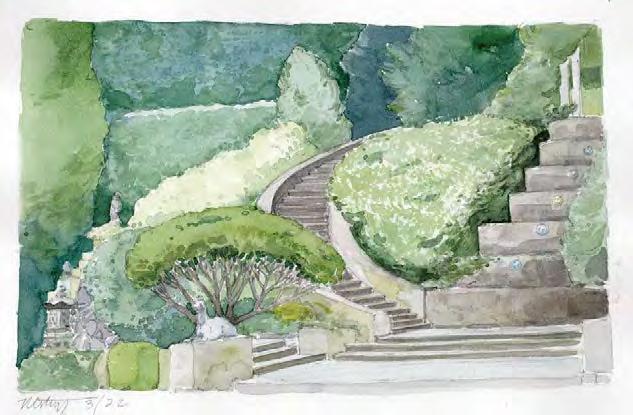

Many thanks to the important voices who have generously agreed to address the multi-faceted and nuanced aspects of this growing field through their essays for this publication. We also appreciate the generous contribution of artist and Garden Conservancy board member Dana Westring; his beautiful illustrations capture both the variety and the joy that gardens offer to all. My thanks also to all members of our national board for their leadership and support of our efforts and to our members, Fellows, and friends whose generous financial contributions made this project possible. Thanks to Carlo Balistrieri for writing eight project profiles for this book. The staff of the Garden Conservancy has also worked mightily to see this book to completion.

I hope you will join us in our mission and continue to find inspiration in America’s gardens.

James Brayton Hall President and CEO