18 minute read

Playworks: A practical reflection on performance art as a means to intersect play and work

Abstract

This article is intended to reflect on how performance art can be a channel through which play and work intertwine. The authors Sven Lütticken and Erving Goffman are used to support the idea that work and leisure have become indistinguishable and that life has become a generalized performance. It is theorized that art and play have characteristics that antagonize the sphere of work under capitalism. Three performances by the author are presented: The Machine Must Go On is about competition and acceleration in the work environment; Slow Woman is about the invisible and undervalued domestic work and consequently the disparities between men and women in this matter and Business Game about the power dynamics involving Mexican workers and American companies.

Advertisement

Introduction

For most people, work is necessary to ensure subsistence. Work determines a lot in a person’s life: their social position, their peers and friends and the free time they have. To get a good job – or in some cases, just any job – anything is valid: excessively long journeys, immigration, devastated mental health, fatigue and suffering.

KEYWORDS labour game competition repetition power capitalism life

Competitiveness in the work environment and exploitative or disproportionate use of power are the topics that instigate and permeate this article, in a theoretical and applied way. The question to be answered is: how can art as play provoke critical thinking about the work environment and its power dynamics? For that, the similarities between art and play, and the relationship with and influence of work on performance art, will be discussed. Finally, these themes will be discussed through three performances by the author.

WORK: COMPETITIVENESS AND POWER

The transition to the post-Fordist system – characterized by specialization of activities, digitalization and immaterial labour – was theorized in 1960 to ‘make human labour increasingly unnecessary, leading to new forms of occupation, of life as play’ (Lütticken 2012: n.pag.).

Such an ideal has not yet been realized and we continue to need human labour in most occupations. The closest thing to ‘life as play’ happens through the ‘work as a game’ mentality that operates in a competitive work environment. This kind of environment ‘increases physiological and psychological activation, which prepares body and mind for increased effort and enables higher performance’ (Steinhage et al. 2017: n.pag.).

Game enters the workspace through competitions and fun breaks held in game rooms, and couches and slides in offices and start-ups – often with younger workforces. Gamification is another strategy used to improve engagement and motivation in the workplace by using videogame elements such as challenges, points and rewards. But gamification can have a negative side because ‘different workers have different attributes, motivators, pay models and jobs that should be taken into account’ (Lewis 2019: n.pag.). Moreover, the game has to be meaningful to the employees in order to give results.

Another common issue is a competitiveness that can become toxic ‘when it loses the “fun” aspect and becomes more about beating others and being the best’ (Schur 2019: n.pag.). These kinds of competitions are influenced by the position held in a company, the degree achieved in studies, or the experience obtained over the years. However, there are other types of non-legitimate power that have existed for centuries and continue to act as a form of privilege and power in the labour market and in society in general. These can be related to gender, ethnicity, social class and more. Some of these divisions and hegemonic structures will be explored later in this article.

Play

The book Homo Ludens (1938) by historian and linguist Johan Huizinga (1874–1945) is, almost hundred years after its publication, still one of the main references for defining play in culture. The author argues that the game was a necessary element for the emergence of culture.

By analysing the semantic origin of the word play, Huizinga distinguishes paidia, a Latin word that means children’s games, which could be translated to play, and agon, a Latin word for games of competition, which would correspond to the word game. However, the author claims that paidia and agon are the same and the words will be used interchangeably throughout this article.

Huizinga (1949) defines play as an activity in a limited time and space with rules. It is a voluntary and free act and that is situated outside of real life, which happens without any need – its only aim being the act itself. These last characteristics are what make it antagonistic in relation to the sphere of work, because ‘playing is a major distraction tempting people away from work, which is the “real business” of living’ (Schechner 2002: 112).

The author explores and identifies how various activities such as war, philosophy, poetry and music share some of the characteristics of play. About war, the author argues that we can only speak of war as a cultural function so long as it is waged within a sphere whose members regard each other as equals or antagonists with equal rights; in other words its cultural function depends on its play quality.

(Huizinga 1949: 89)

Mythology and sacred rituals of the earliest societies originate from play. In the Roman Empire, the policy of ‘bread and circuses’ – where the population was distracted and diverted from political decisions by food and entertainment – shows how important it has been for a long time to the population.

In the nineteenth century, the play component in culture began to fade: ‘these tendencies were exacerbated by the Industrial Revolution and its conquests in the field of technology. Work and production became the ideal, and then the idol, of the age’ (Huizinga 1949: 192).

The twentieth century was marked by a comeback and complete transformation in the social role of play. Spontaneity and superficiality gave way to organized competitions and tournaments on logical thinking and scientific knowledge. Companies and bosses have taken advantage of this change to absorb and exploit the game functions by instilling ‘the playspirit into their workers so as to step up production […] play becomes business’ (Huizinga 1949: 200). Game enters the corporate and neo-liberal sphere as a model of competition established in the labour market.

Performance As Play

For Huizinga, art enters the space of play when it is music, theatre or dance. The author highlights the action involved in the execution and interpretation of these activities in comparison to the plastic arts:

The emotional effect or operation of their art is not, as in music, dependent on a special kind of performance by others or by the artists themselves. Once finished their work, dumb and immobile, will produce its effect so long as there are eyes to behold it. The absence of any public action within which the work of plastic art comes to life and is enjoyed would seem to leave no room for the play-factor.

(Huizinga 1949: 166)

Performance is a kind of art that is expressed through actions made with the body. In line with Huizinga’s ideas, it could be seen as play and can sometimes be confused or merged with theatre or dance.

Repetitive movement is a very present feature in performance art and was widely used by artists such as Bruce Nauman who, in his studio performance

Walking in an Exaggerated Manner around the Perimeter of a Square (1968), does what the title suggests: in his studio, he walks forwards and backwards for ten minutes. Or as in Accumulation (1971) by Trisha Brown, in which movements are repeated and added in a sequence turning it into a choreography. The movement starts with the hands, then arms, then legs and finally the whole body moves.

Play, in comparison, also has a strong relationship with repetition, according to Huizinga:

In this faculty of repetition lies one of the most essential qualities of play. It holds good not only of play as a whole but also of its inner structure. In nearly all the higher forms of play the elements of repetition and alternation (as in the refrain), are like the warp and woof of a fabric.

(1949: 10)

For Richard Schechner, theatre director and university professor, ‘performance means: never for the first time. It means: for the second to the nth time. Performance is twice-behaved behaviour’ (2002: 36). Repetition can increase or reduce the importance of gestures. It can eliminate what is unique by repeating or accentuating features of its original context.

When repeating acts, performance ritualizes them, modifying their meanings. According to writer and artist Anthony Howell, one possible way for this transformation to occur is by transference: a ‘redirection of attitudes and emotions towards a substitute’ (2000: 135), the displacement of meaning from one action or object to another. It can occur in various ways: through the transfer of use, when an object is used out of context or for a different action than usual; or transference of scale, when smaller objects are used to represent larger objects or vice versa. Howell lists eleven types of transference to be used in performances.

Play can always be repeated. However, it is never repetitive because one game is never the same as another. A ritual act has all the characteristics of a game ‘particularly in so far as it transports the participants to another world’ (Huizinga 1949: 18). Likewise, performance is based on the imagination of another reality – a better, different, extraneous one – in order to criticize or reinforce the structures and systems of the world.

Performance becomes a gateway to a fictitious and imaginative world. Performative behaviour happens due to rhetorical deviations that modify the image or the action. Schechner calls this characteristic a restoration of behaviour, that is, ‘me behaving as if I am someone else’ (2002: 34).

Performance As Labour

In 1960, with the emergence of the Fluxus – a group that was experimenting with new kinds of performance involving sound, events, poetry, video and more – performance art gained a closer relationship with daily life.

Fluxus members used routine actions to create art. One example is Allan Kaprow, who created happenings: actions presented from scripts that could involve music, poetry, projections and the participation of people performing. Another example is George Brecht with his event scores: simple instructions to daily tasks such as turning the radio on. This connection with everyday life also created a relationship with labour and consequently a reflection upon the artist’s own work.

The visibility of labour in performance practice therefore corresponds in various ways with broader changes of labour in contemporary society, especially with the immaterial aspect of labour, the production of subjectivity and the performative turn in contemporary culture and society.

(Klein and Kunst 2012: n.pag.)

Additionally, the word ‘performance’ is used in the fields of both work and sport to indicate one’s efficiency and productivity. In that sense, Sven Lütticken argues that work has taken up such a big part of life that one must perform all the time:

You perform when you do your job, but your job also includes giving talks, going to openings, being in the right place at the right time. Transcending the limits of the specific domain of performance art, then, is what I would call general performance as the basis of the new labour.

(2012: n.pag., original emphasis)

This idea is presented by the sociologist and social psychologist Erving Goffman in his book The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1956). By analysing face-to-face interactions, he concludes that people are always acting, trying to control their appearance and manners in order to present themselves in a certain way to others. Goffman says that ‘life may not have much in the way of a play, but interaction does’ ([1956] 1985: 223, translation added). Most of the examples he gives in the book are from relationships and environments of work, concluding that these environments require a performance by the individual.

The concept of ‘emotional labour’, coined by the sociologist Arlie Hochschild, is another form of labour that requires performative behaviour. Emotional labour requires a ‘management of feeling to create a publicly observable facial and bodily display […] and a worker to produce an emotional state in another person while at the same time managing one’s own emotions’ (Hochschild 1983: 7). The author decided to investigate further the works of flight attendants and bill collectors, but there is a wide range of jobs that require a simulation of emotions such as call centres, health workers, attendants, childcare, etc.

It is possible to say that social life always requires some kind of performance, either behavioural or emotional, but taking into consideration the research of both authors cited above, in work environments, performance is generally more evident and requires more effort. The conduct of a work team is nearly always different when the boss is present, and a call-centre attendant will always show a smile in their voice.

Evidence of this is a New York Times study (Goldberg 2022) that found that two-thirds of remote employees want to remain working from home after two years since the beginning of the pandemic. The workplace culture was the characteristic which weighed most heavily in this decision. Small talk and even microaggressions were positive points for the research participants, demonstrating that the behaviour and performance required on workplace are displeasing.

The Machine Must Go On

The Machine Must Go On

(Manfredini 2021) is a video performance made on an escalator in a metro station in the city of Porto, Portugal. The action performed is that of a constant movement, travelling up the escalators and then walking back down the stairs, repeating this action endlessly. Members of the public disrupt the movement of both performers by standing still on the escalator, forcing the performers to slow their pace or to pause.

It is possible to perceive the performance as a game between the performers and the interweave of play with work. To begin with, the performers meet, overtake and miss each other again and again as if they were competing. They are dressed in monochromatic colours, a metaphor for board game pieces or work uniforms. The rhythm and repetition are attributes related to game itself and also, from the speed of the video, it is possible to see them as characters in a video game.

The escalator refers to Fordist labour, in which as factory workers would have repeated the same toiling movements for hours on an assembly line that uses a conveyor-belt. It also symbolizes daily commuting – which can be long, stressful and tiring in itself – added to the effort and fatigue of work. The scholar and activist Silvia Federici would say that we are ‘moulded by the capitalist-work discipline to confront one’s body as an alien reality […] in order to obtain from it the desired results’ (2004: 152). Under these circumstances, the human body becomes like a gear and consequently atrophies.

The effort made by the performers to go up and down the escalator can be likened to the myth of Sisyphus, who in Greek mythology was given a punishment in which he had to roll a rock uphill, even though it would inevitably come back down again and again. This myth suggests that ‘there is no more terrible punishment than useless and hopeless work’ (Camus [1942] 2016: 121, official translation).

Another characteristic that is noticeable in the performance is the acceleration. It refers to the speed of the globalized and online world in which new information is spread instantly. It is also about the constant state of hurry and the feeling that 24 hours are not enough for everything that needs to be done. These are recurrent symptoms in today’s society that can lead to anxiety, burnout and exhaustion. The video is made in a loop; the end and the beginning coincide, highlighting the vicious cycle that performance – and work – can become. It questions the lack of time and the impact it has in modern lives, and it is a reminder to use time in a more pleasurable and valuable way.

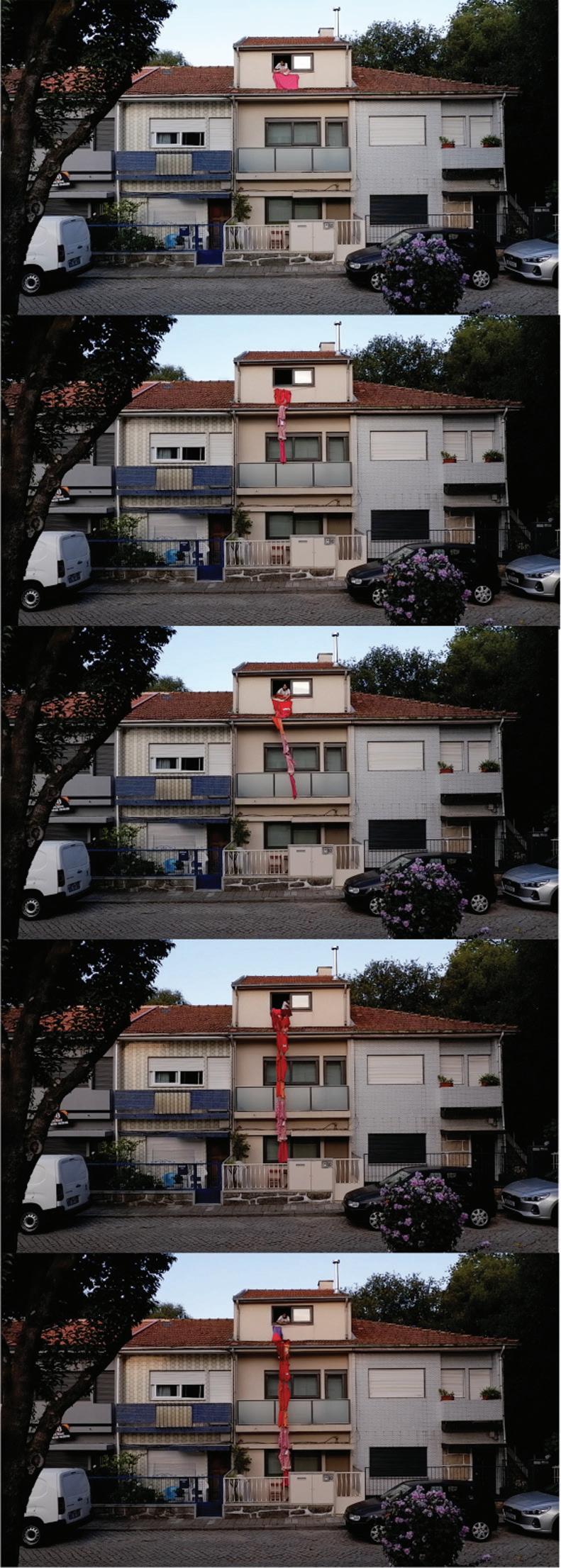

Slow Woman

Slow Woman (Manfredini 2021) is a performance in which a woman at a window in an apartment hangs clothes on a clothesline. This could be a common scene in Portugal, where clotheslines seen in windows and balconies are part of the country’s aesthetic. But this activity is deviated by the actor spreading out and pinning the clothes together, until they reach the floor, forming a type of banner hanging from the apartment window. Passers-by continue walking normally, until someone unexpectedly shows interest by asking what is happening.

This performance is a critique of the power imbalance between men and women in a family setting and consequently in their responsibilities and household chores. According to the Office for National Statistics, British women did almost 60 per cent more of the unpaid work, on average, than men in 2016. It questions: who washes and hangs these clothes? Who folds and puts them away? It is nearly always a woman who is in charge of the care economy that sustains a patriarchal system.

This work could be put in dialogue with the practice of the artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles, whose Manifesto for Maintenance Art (1969) turned her housewife routine into artistic work. She managed to give visibility to the gruelling work of maintaining and cleaning a museum, and the people who do it. In that sense, Lütticken states that ‘cleaning and caring would be the most common forms of general performance if they were not forced to be invisible and socially denigrated as rote routine’ (2012: n.pag.).

The performative action takes place through adiectio – or addition – that in a performative dimension is related to a repetitive action that adds and accumulates, modifying the normal behaviour of an action (Almeida 2010). This accumulation also shows that housework is an unending and exhausting activity. Consequently, the invisible act of taking care of clothes is emphasized through their growth and volume into the public space. There is a transfer of scale and weight on this clothesline, also making this performance an ongoing sculpture displayed to pedestrians in the neighbourhood.

Slow Woman also shows the potential of art to emerge anywhere and by anyone, bringing to light the concept of social sculpture by the German artist Joseph Beuys. The ‘slowness’ alluded to in the title is based on what Milton Santos calls a ‘slow man’ (2001: n.pag.). The slow individual is the one who does not condone the speed of the current world and therefore resists the neo-liberal velocity that is seen by the author as an alternative to competitiveness and consumerism.

The housewife is playing with her duties. She is repeating, transforming and questioning obsolete narratives. The game allows the woman to imagine a new situation where she is empowered and playful. Lastly, she can be seen as capable of patiently resisting hegemonic, capitalist and gendered narratives.

Business Game

Piñata is a game where a blindfolded person, who is spun around many times until they get dizzy, tries to hit an object with a stick until it breaks and the prize that is hidden inside falls to the ground. The object is typically made of papier-mâché today, but in the past it used to be made of pottery.

The game was initially significant in the Catholic tradition, where the piñata was star-shaped with seven points representing the seven sins, and the players would be turned around 33 times to represent the age of Christ. This religious significance is not important to many engaging in the tradition today, but it is still commonly played at birthday parties and holidays – especially at the Las Posadas, a religious festival that takes place in December. The piñatas are filled with candies and fruits, and they are shaped like cartoon or movie characters to draw children’s attention and to make more sales.

The craft is usually passed on from generation to generation, particularly in Mexican towns known for this tradition. In the city of Acolman, hundreds of jobs are generated from piñatas workshops, and in San Juan de la Puerta about four hundred families are dedicated to the production of piñatas to be exported to Chicago, Texas and Atlanta (Redacción Am 2017: n.pag.).

In the past few years, companies such as Marvel have started legal battles against piñata makers in order to defend their intellectual property rights. Police have seized piñatas of Spiderman, Captain America and other characters throughout the United States, as well as in airports and along the US–Mexico borders (López 2010: n.pag.).

This background is the central theme of the performance Business Game (Manfredini 2021) that shows a person beating a piñata in a public space. The object is violently breached and when it is broken, banknotes and coins fall to the ground.

This work is about a dispute between Mexicans and Americans, and in a broader sense, between developed and underdeveloped countries. Additionally, the piñata battle described above is related to other exploitative situations, such as American multinational companies and industries, which employ Mexican people for low wages and under precarious working conditions (North American Production Sharing 2019: n.pag.). This imbalance in social and labour conditions is also a cause of common prejudices against Mexicans and leads to high rates of drug trafficking and migration, which turned into a national discussion and is used to justify the building of a border wall to prevent illegal Mexican crossings.

The piñata has long ‘been used as a form of practical social commentary’ (Hernandez 2021: n.pag.), and more than a simple commodity, it expresses Mexican cultural resistance. It is a handcrafted object that takes up a long time to be made, especially because of the glue, which needs to be totally dry before another layer is put on. Thus, it challenges the normal course and speed of production in the twenty-first century.

Play and labour are directly related and the piñata becomes a metaphor for competition, capitalism and border issues, exposing a highly profit-oriented neo-liberal system.

Conclusion

This article is born from the understanding that the world today is essentially ruled by work, power, efficiency and haste. According to Boris Groys, ‘a genuine political transformation cannot be achieved according to the same logic of talent, effort, and competition on which the current market economy is based’ (2014: n.pag.).

Play has become problematically intertwined with work and has been used to legitimize unhealthy productivity through the establishment of competitive and ‘fun’ work environments. However, one of the characteristics of play is that there is no real purpose apart from entertainment and excitement, making it antagonistic to work culture.

It has been argued that performance and labour have an entangled relationship, and therefore art can create and re-create actions and situations by imagining, re-envisioning and performing things differently, allowing people to escape from the mundanity of everyday life and also to transform themselves. The performances discussed in this article manifest that play can be used as a device to criticize the mechanized routine of contemporary life and work conditions.

Finally, it is also important for workers to demand not only regulation, fair wages and working hours but also a behavioural reformulation and reinforce the importance of leisure time. If everyone is aware that they are participating in a performance in their lives and workplaces, it should be possible to imagine a more empathetic and genuine relationship with work and colleagues.

References

Almeida, Paulo Luís (2010), ‘La Dimensión Performativa de la Práctica Pictórica – Análisis de los Mecanismos de Transferencia de Uso Entre Campos Performativos’, Ph.D. thesis, Bilbao: University of the Basque Country.

Bishop, Claire (2012), Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, London: Verso.

Camus, Albert ([1942] 2016), O Mito de Sísifo, Rio de Janeiro: BestBolso.

Federici, Silvia (2004), Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation, New York: Autonomedia.

Goffman, Erving ([1956] 1985), A Representação do Eu na Vida Cotidiana, Petrópolis: Editora Vozes.

Goldberg, Emma (2022), ‘A two-year, 50-million-person experiment in changing how we work’, New York Times, 10 March, https://www.nytimes.

com/2022/03/10/business/remote-work-office-life.html. Accessed 11 May 2022.

Groys, Boris (2014), ‘On art activism’, e-flux, 56, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/56/60343/on-art-activism/. Accessed 10 March 2022.

Hernandez, Samanta H. (2021), ‘The art, politics, and craft of piñatas’, Hyperallergic, 10 October, https://hyperallergic.com/682158/the-art-politics-and-craft-of-pinatas/. Accessed 9 March 2022.

Hochschild, Arlie (1983), The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Howell, Anthony (2000), The Analysis of Performance Art, Amsterdam: OPA.

Huizinga, Johan (1949), Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Klein, Gabriele and Kunst, Bojana (2012), ‘Introduction: Labour and performance’, Performance Research, 17:6, pp. 1–3, https://doi.org/10.1080/135281 65.2013.775749. Accessed 15 February 2022.

Lewis, Nicole (2019), ‘Be careful: Gamification at work can go very wrong’, SHRM, 28 February, https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-topics/ technology/pages/gamification-at-work-can-go-very-wrong.aspx Accessed 21 June 2022.

López, Primitivo (2010), ‘Decomisan piñatas mexicanas “piratas” en Laredo, Texas’, Hoy Tamaulipas, 24 June, https://www.hoytamaulipas.net/ notas/12450/Decomisan-piniatas-mexicanas-piratas-en-Laredo-Texas. html. Accessed 9 March 2022.

Lütticken, Sven, (2012), ‘General performance’, e-flux, 31, https://www.eflux.com/journal/31/68212/general-performance/. Accessed 28 February 2022.

North American Production Sharing (2019), ‘Benefits of US companies doing business in Mexico’, NAPS, 8 September, https://napsintl.com/mexicomanufacturing-news/benefits-of-us-companies-doing-business-inmexico/. Accessed 14 April 2022.

Office for National Statistics (2016), ‘Women shoulder the responsibility of “unpaid work”’, Office for National Statistics, 10 November, https://www. ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/articles/womenshouldertheresponsibilityofunpaidwork/2016-11-10. Accessed 27 March 2022.

Redacción Am (2017), ‘Artesanos Traspasan Fronteras’, AM, 22 December, https://www.am.com.mx/noticias/Artesanos-traspasan-fronteras20171222-0137.html. Accessed 27 March 2022.

Ruhi, Umar (2015), ‘Level up your strategy: Towards a descriptive framework for meaningful enterprise gamification’, Technology Innovation Management Review, 5:8, pp. 5–16, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1605.09678. Accessed 21 June 2022.

Santos, Milton (2001), ‘Elogio da lentidão’, Folha de São Paulo, 11 March https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/fsp/mais/fs1103200109.htm . Accessed 5 July 2022.

Schechner, Richard (2002), Performance Studies: An Introduction, Abingdon: Routledge.

Schur, Katelyn (2019), ‘The toxicity of a hyper-competitive work environment’, ApplicantOne, 20 December, https://www.applicantonesource.com/blog/ toxic-competition-workplace. Accessed 7 March 2022.

Steinhage, Anna, Cable, Dan and Wardley, Duncan (2017), ‘The pros and cons of competition among employees’, Harvard Business Review, 20 March,

Delivered by Intellect to: Gabriela Rangel Cunha Manfredini (33326404) IP: 168.182.233.154 On: