45 minute read

At Home on Earth | Kyle Kramer

Kyle Kramer

Kyle is the executive director of the Passionist Earth & Spirit Center, which offers interfaith educational programming in meditation, ecology, and social compassion.

Advertisement

He serves as a Catholic climate ambassador for the US Conference of Catholic Bishopssponsored Catholic Climate Covenant and is the author of A Time to Plant: Life Lessons in Work, Prayer, and Dirt (Ave Maria Press, 2010). He speaks across the country on issues of ecology and spirituality.

He and his family spent 15 years as organic farmers and homesteaders in Spencer County, Indiana.

EarthandSpiritCenter.org

WANT MORE? Visit our website: StAnthonyMessenger.org

A Different Take on Fasting

As a zealous young man, I often undertook pretty extreme Lenten fasts. One time, back in graduate school, I even fasted from electricity. I still chuckle about how strange my friends and neighbors must have thought I was back then—and, of course, they were absolutely right.

Looking back, I see how much those fasts were fueled not only by the enthusiastic idealism of youth, but also by my need to flex my moral muscles, to feel self-righteous. I was proud of the degree of deprivation that I undertook—and, if I’m honest, I felt some disdain for those who couldn’t or wouldn’t go to such extremes as I had.

As I’ve aged, my idealism and moral muscle power aren’t quite what they were back in my 20s. I don’t attempt such look-at-me kinds of fasts anymore. I’d like to hope that this stems from a bit more spiritual maturity, more humility, less need to impress myself or others, and a clearer focus on the spiritual invitations of the penitential season.

But as I think about the new generation of young climate activists, such as Varshini Prakash and the Sunrise Movement or Greta Thunberg and her school strikes for the climate, I’m reconsidering. These young people are asking hard things of us who are older. They see clearly that the world we are handing to them is damaged and degraded. They understand, in stark terms, that if we continue with our too-little, too-late, business-as-usual approach, the world will pass various environmental tipping points from which we can’t recover—and that they, in their lifetimes, will experience the brunt of the ensuing catastrophes. In the face of such a bleak future, they are demanding that we change our lifestyles, our laws, our economics, the very assumptions and habits of modern first-world living—an entire paradigm shift that must happen at scale and at speed, which is no small thing.

I think that, at our core, we also want what they want. We don’t want to preside over the kind of destruction that is happening right now. We want a kinder, gentler, thriving, cooperative world—for them, for generations yet unborn, and for ourselves. The pleasures and satisfactions offered by our current way of living pale in comparison to the kind of just and equitable future they are asking us to help create.

It’s no exaggeration to say that we are addicted to using a lot of energy and natural resources to support our current way of life. In fact, according to the article “2,000

Watt Society,” in the United Nations University magazine Our World, we Americans use about six times more energy than our global “fair share” and 40 times more than the average Bangladeshi.

How can we make the changes that the younger generations rightfully demand of us? It feels impossibly daunting, so the temptation to do nothing is very great. But while any one person’s impact may seem small, each of us can do what is ours to do. Both as a Christian and as a world citizen, I want to do something more, and I think the Lenten season may be a way to move toward the future I want to help create.

FASTING FOR THE ENVIRONMENT

Lenten fasting has traditionally been about food. Given that a meat-heavy diet is more than twice as environmentally impactful as a plant-based diet, couldn’t that be a place to start? What if, for the season of Lent, we ate half as many animal products as we usually do—or even, if we want to be hard-core, none at all?

Another potential Lenten fast is from consumption. What if, for the season of Lent, we decided to cut in half our purchase of nonessential items or even cut out such purchases entirely?

We might also look at our use of energy—for our household and our transportation. What if we made at least one energy-saving investment in our home, whether that is installing LED light bulbs or a more efficient furnace? Or perhaps we could cut out any unnecessary travel. Given the restrictions of the pandemic, this should be an easy lift.

Almsgiving is another aspect of the Lenten season. Why not choose to direct some of our resources toward organizations—faith-based or secular— that are working hard to create a more livable future for all? What if we made a commitment to purchase renewable energy credits, which help offset the environmental impact of our energy use?

IN GOD’S HANDS

The third element of Lent is, of course, prayer. Because the task before us is so all-encompassing and intimidating, prayer is essential. It not only sustains our own hope, but I believe prayer also has powerful, worldchanging effects far beyond our own sphere. I don’t pretend to understand how this works, but as a person of faith, I believe that it does—not as an excuse to avoid doing something “tangible,” but as a complement to it. Prayer really can move mountains, and that is the scale of what is required now.

The needs of our historical moment are pulling me out of my middle-age comfort zone into a sharper-edged sense of commitment. And I’d like to think that the deprivations of the pandemic have both helped me pare things down to a more essential level and toughened me up enough to live out my commitments more seriously. The Lenten season provides a wonderful opportunity to make all of this tangible.

The question, of course, is whether we can do this in a way that rises to the seriousness of the moment and yet somehow holds our own actions lightly at the same time: caring deeply and yet unattached to outcomes. That’s the paradox, which only the faithful, contemplative imagination can manage. Our future may be in our hands, but we are in God’s.

HELPFUL

TIPS RESOURCES According to Founders Pledge and Giving Green, the three most effective charities working on US climate policy are the Clean Air Task Force, Carbon180, and the Sunrise Movement Education Fund. Faith-based charities working on climate change issues are the Catholic Climate Covenant, the Franciscan Action Network, and Interfaith Power and Light.

If you want to quantify your environmental impact, especially in regard to climate change, you can find carbon footprint calculators at the Environmental Protection Agency, The Nature Conservancy, CarbonFootprint.com, the Global Footprint Network, and others.

Flipping the Questions

Asking yourself these three questions could change your mindset, putting you on a path that follows Jesus’ footsteps.

By Mary Ann Steutermann

Like most of us in the developed world, I have too much stuff. Just last weekend, it took a ridiculous amount of time to find a jacket I wanted to wear to work, all because my closet was simply too full. It was past time to go through it all and give away what I no longer needed.

Also like most of us, I tackled the task KonMari style, the popular method of decluttering popularized by organizing consultant Marie Kondo in her best-selling book, The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up. Kondo suggests deciding which belongings should stay and which should go by asking of each, “Does it spark joy?”

I gave it a shot, but I failed miserably. That pair of extrathick wool socks that I haven’t worn in years? It doesn’t bring me joy in this moment, but it certainly might if next winter comes with subzero temperatures. And that lovely evening gown I only wore once when I was thinner? It doesn’t excite me right now, but what if I dropped a couple dress sizes? The wool socks and evening gown seemed to have too much “potential joy” for me to part with them.

I realized then that the question about joy was the wrong one to ask. On a second attempt at tackling the clutter, I asked a different question: “Did I even know this item was in my closet before I started looking?” That one did the trick. No, I didn’t remember that those wool socks or that old evening gown were in my possession before I started the purge, so they had to go. They joined two big boxes full of other items that I didn’t remember owning but were now ready for new homes, regardless of any future joy they may have promised. Now when it comes to decluttering, I have a new question that guides my choices.

In a very real sense, Christianity is all about flipping the questions. The Jesus we meet in the Gospels continually turned the tables on more than the money changers in the Temple. He flipped the very foundations of the Jewish power structure of the time and the interpretation of religious law. He flipped people’s understanding of who is worthy and how God’s mercy works. And he flipped the meaning of death completely on its head. Unfortunately, some Catholic Christians today hold fast to the Son of God we know from Church doctrine but forget about the Jesus of Nazareth we meet in the Gospels. To reclaim the full truth from both, we may need to flip some of our usual questions.

PUSH VS. PULL

There’s one question that every young person, regardless of country or culture, loathes: What do you want to be when you grow up? That question haunted me through childhood and well into adulthood. At one time or another, I wanted to be a psychiatrist, bus driver, nun, social worker, and computer programmer. And on it went, that desperate search for a future identity, careening from one career aspiration to another.

Eventually, I gave it up. During my freshman year of college, I decided to be “undecided.” That’s when a strange thing happened. I stopped obsessing about the question, “What do I want to be when I grow up?” and started asking myself, “What does the world need me to grow into?” I stopped searching for what I thought I’d like best and tried to listen for how I could best contribute to the work of the Holy Spirit.

Ironically, deciding how I could best serve led me to the fun and fulfilling career I had long sought. Thirty years later, I can say that choosing to become a Catholic school teacher was the best decision I’ve ever made. But the truth is that I didn’t explicitly choose education as a career. Through months of prayerful discernment, it chose me. It wasn’t until I flipped the question of “What do I want to be?” into the question of “How am I called to serve?” that the path became clear.

I think Jesus learned that same lesson, just more quickly than I did. I imagine Jesus’ friends and family were taken aback by his choice to be anything but a carpenter, the profession of Joseph and probably Joseph’s father and grandfather before him. But Jesus could not “push” himself into a role that was anything other than what he was called to do. He let the Holy Spirit “pull” him into his ministry, and in doing so, he transformed the world.

WHY VS. HOW

Human beings are wired to seek meaning. As Christians, we know that we come from God and will return to God, so it only makes sense that the space in between is something beautiful, logical, and meaningful. Too often, though, it’s none of these.

When both parents and their three young children are tragically killed in a car accident, it’s none of these. When the diagnosis involves the phrases stage 4 and nothing we can do, it’s none of these. When a loved one’s mental health issues eventually lead to suicide, it’s none of these.

Still, we continue to ask why. Why did this happen? Why didn’t God prevent it? Why do good people suffer? We try to fill in the blanks with rational explanations for irrational tragedies. Perhaps God is trying to teach us a lesson or help us grow in character and moral fortitude. Might God be testing our faith or preparing us for some unknown future? No matter how superficially logical they may seem, each of these answers comes up short. The God of love we know through Jesus could not possibly be so small and vindictive.

Why is a handy question to ask when junior comes home with a bloody nose or the bank manager says the check bounced or we want to address the problem of homelessness in our city. When applied to the meaning of life, however, why doesn’t work as well. So I’ve learned to flip the why question into more of a how. Instead of “Why must I suffer?” I now ask myself, “How can I be brave?” The answer to this question has been different at different times in my life. Once, the answer was to reach out to someone who had hurt me deeply. Another was to rip off the Band-Aid and admit my elderly parents into a nursing home. And yet another time, the bravest thing I could choose to do was to get out of bed in the morning.

Jesus, too, was no stranger to the struggle for meaning amid pain. Hanging on the cross before taking his last breath, he cried out, echoing the words of Psalm 22, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” But Jesus’ whole message was about helping us answer the hows. How should I treat my neighbor? How often should I forgive? How am I to pray? How must I deal with my enemy? In short, Jesus’ ministry was all about teaching us the answer to this question: “How am I to live?” Flipping the question from why to how not only helps us grapple with the question of meaning, but also gives us a practical road map for moving forward.

FAIR VS. JUST

By far, my least favorite parable in the Gospels is the one about the workers in the vineyard (Mt 20:1–16). In it, a vineyard owner goes out to find laborers early one morning and sets them to work. Then, at about 9 a.m., he discovers more idle workers and sends them to join the others. He repeats this process at noon, 3 p.m., and even 5 p.m., shortly before the end of the workday. But when it’s time to pay the laborers, he pays those who arrived latest in the day and worked the least a full day’s wage. Naturally, those he hired early that morning and who worked all day long expected more, but no—they received the full day’s wage, just like those who worked very little.

The parable goes on to say that “they grumbled against the landowner.” I can hear them saying, “But that’s not fair!” and probably much worse. We humans expect the greatest rewards to go to the most deserving individuals, and we have a powerful need to keep score to ensure that they do.

But the vineyard owner has a fascinating response to those who felt they deserved to be paid: “I am not cheating you. Did you not agree with me for the usual daily wage?” I can imagine the workers’ response: “Well, yes, but . . .” The vineyard owner counters with a clever question: “Are you envious because I am generous?”

This parable has always been hard for me because I believe fairness is a good thing. And it is. It’s just not the most important thing. I’ve learned to flip the question, “What do I deserve?” and instead ask, “What does my neighbor need?” In doing so, I let go of my self-centered, regimented grip on fairness to make room for the more compassionate, loving embrace of justice. Surely, justice is the greater good.

BE TRANSFORMED

Jesus was all about turning things upside down. The religious authority of the Pharisees and scribes gave way to the sincere faith of some prostitutes and tax collectors. An eye for an eye was replaced with turning the other cheek. The darkness of death was transformed into new life. When we flip some of the questions that guide our paths forward, we open ourselves to the possibility of that same transformation in our own lives.

Mary Ann Steutermann is the director of campus ministry at Assumption High School, a Catholic all-girls school in Louisville, Kentucky. She’s also a freelance writer whose articles have been published in this magazine and on the popular Catholic website BustedHalo.com. Mary Ann lives in Louisville with her husband and son.

The Society of St. Vincent de Paul

MOVING MOUNTAINS WITH CANNED GOODS

When a classmate challenged Blessed Frédéric Ozanam to put his faith into action in 1833, he took it to heart. Today his legacy lives on through this organization.

By Katie Rutter

It probably started when a mother noticed that her not-solittle boy’s ankles were showing. She sighed; all his clothes seemed to be perpetually shrinking.

She gathered the outgrown trousers along with a few other items and dropped them off at the local St. Vincent de Paul conference. It was a tiny donation forgotten as soon as she was home, but more than 60 years later, that gift is still remembered by the recipient.

“I remember walking to this little building that St. Vincent de Paul had in Elkhart, Indiana, and getting clothes to go to school,” recalls Ed Dolan, now 73.

He was 10 or 11 at the time, and his family had hit a rough patch. His dad, the breadwinner, had lost his job. With

KATIE RUTTER no income, the family turned to St. Vincent de Paul, which supplied Ed with those donated pants and other outfits to get him through the school year. Ed believes that the volunteers also gave his family enough food to fill their cupboards.

“That little time period always stuck in my mind—that our family received help at one point . . . I never forgot,” he explains.

The impact of those secondhand trousers has since multiplied a hundredfold. Inspired by his childhood experience, Ed spends nearly every day volunteering at his hometown St. Vincent de Paul conference. His pickup truck, with a blue St. Vincent de Paul bumper sticker, circles the neighborhoods of Bloomington, Indiana, picking up furniture donations and distributing them to families in need.

To him, it’s the least he can do after the generosity of others saved his own family from dire straits. “I’m giving back what my family received so many years ago,” he says.

FAITH IN ACTION

This story of a small donation making a huge difference is repeated innumerable times. In this country alone, the Society of St. Vincent de Paul serves 4,400 communities. Lay volunteers, known as Vincentians, raise money and collect material goods to provide the necessities of life: food, clothing, emergency housing, financial assistance for rent and utilities, prescription medication, education, and help with transportation.

Though many conferences are known for running thrift shops, the organization exists entirely for charity. Any profits are given back to the poor of the community, and material assistance is given free of charge to those who cannot afford even the lowest prices.

The national society estimates that they gave away more than $1.2 billion in tangible and in-kind services in 2017. In Bloomington, Ed and his colleagues distributed over 4,800 pieces of furniture in a single year, all provided at no cost.

Every single one of those pieces, piled high into Ed’s truck before being unloaded and given away, could tell a story. More times than he can count, community members have recognized Ed’s blue St. Vincent de Paul shirt and stopped to thank him, describing how the society helped them out of a tough spot or provided a bed to sleep in after they got off the streets.

One grateful recipient posted a photo of her new chairs and table on the organization’s Facebook page, commenting that her space finally felt like home. Another grateful mother commented, “They have helped me and my children in so many ways!”

“People do realize that we’re not doing this just because it makes us feel good; it is also because it’s responding to a call,” Ed says. “I feel that as a person who professes to believe in Jesus Christ as the son of God, part of the profession of faith is putting my faith into action,” he adds, echoing a belief that goes back to the very founding of the society.

The Society of St. Vincent de Paul was begun by a single individual shortly after the French Revolution. Blessed Frédéric Ozanam, a Catholic student at the University of Paris, was challenged by a fellow student: “What do you do besides talk to prove the faith you claim is in you?”

Frédéric took that challenge to heart. Gathering a few friends, he founded what he called the “Conference of Charity” in May of 1833 and personally tended to the poor in the tenements of Paris. Before long, others joined the group and the society placed itself under the patronage of St. Vincent de Paul, a 17th-century saint known as the “Father of the Poor” because of his dedication to missions and serving those who are in need.

Volunteer Ed Dolan makes his rounds nearly every day, picking up donated furniture and distributing it to people in need. For Ed, it’s a way to give back and put his faith into action.

Almost as if to prove that the power of Jesus, the multiplier of loaves himself, was at work, Frédéric’s idea spread like wildfire. Before his death in 1853, conferences could be found throughout Europe. Today, Vincentians serve in 150 countries across five continents.

LOAVES, FISHES, AND FORKLIFTS

Loaves, and especially nonperishable items, continue to multiply miraculously in the hands of the Vincentians.

Catholic families are as familiar with charity drives as they are with the creed. The request goes out, and the faithful gather up cans of corn, carrots, and peas from pantries and store shelves. Children lug bulging grocery sacks back to their school and get a sticker or extra credit as a reward. Adults drop the bags off at their home parish and hardly think of the canned goods again.

Most never know that, through the efforts of these dedicated volunteers, those items feed thousands. In Indianapolis, the St. Vincent de Paul Council hosts what they believe to be the largest food pantry in the Midwest, if not

INTERNATIONAL VINCENTIANS

COVID-19 assistance in Kenya

Flood relief in India Visiting the elderly in Thailand

Health care in Lebanon

in the country. Traversing a sprawling warehouse, an army course offered for free by many St. Vincent de Paul conferof volunteers empty the grocery sacks and sort the contents. ences. Those who attend meet once a week to learn about the Cans of peas are dropped into a pallet-sized box with the essential resources needed to live a more stable and prosperrest of the peas. Boxes of macaroni are stacked neatly on a ous life. They are asked to assess themselves and to plan how freestanding shelf. they can change their own situation. Attendees also receive

Forklifts transport the filled boxes to another room, information about community resources. where more Vincentians prepare balanced-diet boxes of “They write a plan out, but it’s not a pie-in-the-sky plan. food for their guests. During normal times, the Indianapolis It’s a step-by-step, how do I get there,” explains Domoni group could expect to serve about 3,000 families each week. Rouse, coordinator of the Changing Lives Forever program During the coronavirus pandemic, that number increased to in Indianapolis. “If [they] want to go to school, they have 3,700 or more. to write all the steps to get there—what’s the financial part,

Before the pandemic, families would wind their way what’s the childcare part, the transportation part, the study through the warehouse in aisles created by the huge boxes of part?” she explains. food, selecting items and placing them into a grocery cart. Like John, many of the graduates finally achieve stability, When social distancing orders came in place, families would which means they no longer have to turn to a food pantry. pile into cars instead and wait their turn in a long queue They can give to others the assistance and the knowledge snaking through the St. Vincent de Paul parking lot. The line that they themselves have received. ends in a tent, where smiling volunteers lower boxes of food “I saw one person in particular,” Domoni recalls, “having into the trunks of cars. her first savings account, and she said, ‘What In all cases, however, one of the first faces that guests see is John Thomas. Usually he is “We try to think I learned in the session, I taught my daugh ter, and she got a savings account too.’” dressed in a neon-yellow reflective jacket and of ourselves as is directing cars into the parking lot. John has not just paying ONE BODY, MANY MISSIONS been a security guard at St. Vincent de Paul a utility bill or Nationwide, it is hard to overstate the since 2017, braving rain, snow, and ice to helping with rent, number of ways that Vincentians serve serve those seeking help. but really trying their brothers and sisters. In most of the “This is like a family. I go to them, or some come to me, if I have something going on in my life,” he says, describing the Vincentians to see the face of Christ in those we 4,400 communities served by conferences, volunteers give out food, clothing, financial assistance, and educational resources. But he works with every week. serve.” the generosity does not end there.

The first time John came to this building, —Deb Smith In New York City, Vincentians visit the however, he was seeking help himself. In the sick and imprisoned, regularly spending cold of January 2017, John was between jobs time at nursing homes and correctional and needed food. For him, the canned goods stacked neatly facilities. Volunteers also bring dinner to families staying into a box were more than nourishment; they were the lure at the Ronald McDonald House while their children are in that led him to a new life. nearby hospitals undergoing treatment for serious illnesses.

“I started turning things around,” John recalls. “I started The St. Vincent de Paul Society serving central and northtelling people about the program because the program ern Arizona boasts its own medical and dental clinic, serving changed my life around.” low-income families. The group also tends nearly an acre of farmland that supplies a community kitchen with fresh BREAKING THE CYCLE fruits and vegetables. What John describes as “the program” is known in In the large metros of Los Angeles and Detroit, Indianapolis as Changing Lives Forever and is called Getting Vincentians provide disadvantaged kids an opportunity to Ahead by other St. Vincent de Paul conferences across the experience the joy of nature. The councils in both of these country. Vincentians have learned that the goods donated by cities host summer camps at low or no cost, with Detroit the community, such as clothing and canned foods, pro- offering a special session for grieving children who have vide a powerful opportunity to meet those caught in a cycle experienced the loss of a family member or friend. of poverty. Instead of only providing a handout, they also Vincentians in Chicago take their thrift stores one step provide a hand up and tell their clients about an educational, further, hosting a “Giving Store,” where those who are life-changing opportunity. reentering society after incarceration can receive clothing,

“I try to let people know about the Changing Lives shoes, coats, and other items. program,” says John. “[As a security guard] I meet lots of The St. Vincent de Paul councils of North Texas and different people, talk to them, encourage them—be a better Cincinnati both host pharmacies that dispense free prescripadvocate for yourself; turn your life around.” tion medication to those who cannot afford it, most often

Getting Ahead, or Changing Lives Forever, is a 16-week for chronic, treatable conditions such as heart disease and

Michael Vanderburgh (left), executive director of the Society of St. Vincent de Paul, Dayton, stands with Jim Butler, who served in the disaster relief division and has been a volunteer for 40 years. Participants follow pandemic safety protocols to attend a Getting Ahead class in Dayton, Ohio, where they learn about strategies and resources that can help them regain their economic footing. Many graduates go on to help others on the path to a more stable future.

diabetes. Texas Vincentians estimate that in 2018, the group gave out nearly 1,000 prescriptions valued at about $150,000.

THE FACE OF CHRIST

Most importantly, however, the free material goods, visits, outreach, and education sessions provide Vincentians the opportunity to achieve an even grander goal: building friendships. This is the key to their ministry, the breath of life that prevents clients from becoming numbers lost in a cold distribution system.

“We try to think of ourselves as not just paying a utility bill or helping with rent,” explains Deb Smith, the manager of conferences at the St. Vincent de Paul Council in Dayton, Ohio, “but really trying to see the face of Christ in those we serve and providing the opportunity for those we serve to see the face of Christ in us.”

Over the course of three years, Deb, and her colleagues at St. Vincent de Paul in Dayton, became as close as family to their client Chris.

Chris first came to the downtown St. Vincent de Paul pantry unemployed and in need of food. His career as a baker had been cut short by a severe car accident, which broke his back and neck, and the subsequent need for rotator cuff surgery. Insult was added to injury as he battled for disability and insurance coverage for surgical procedures and physical therapy.

He used to bake bread, donuts, cakes, and Danishes, but by the time he came to St. Vincent de Paul, Chris could barely move his right arm. “If it wasn’t for Deb, I probably would have given up. There were some times I would come into the Getting Ahead class, I’d be in tears almost. I’d be like, ‘I just can’t do this anymore,’” he recalls.

Deb and the volunteers didn’t give up, and Chris successfully finished the course. Even after he graduated from the Getting Ahead class, Deb kept in touch. They talked regularly on the phone, and volunteers sent cards on Chris’ birthday and holidays. Vincentians drove him to surgeries and stayed through the procedure to drive him home. They celebrated and gave baby supplies when he and his wife welcomed their firstborn son in 2018. They provided bus passes to get him to physical therapy and connected him with a clothing outreach that provided professional outfits as he started landing job interviews.

“The people are great; they will do anything for you,” Chris glows, speaking with St. Anthony Messenger while en route to a promising job interview. “I honestly don’t know what I would have done without them.”

‘THE LEAST OF THESE’

Hope. It’s the unseen gift handed to millions by the volunteers of St. Vincent de Paul. They, in turn, feel the need to share the hope that they have received. Some build resilient families. Others contribute meaningful work to their community. Still others offer their time as volunteers. So the gift continues on, creating larger ripples with each passing moment. Sometimes, it’s hard to believe that those waves began with a pebble.

For Chris and John, this journey to hope began with a bag of nonperishable items. For Ed, it started with clothing for school. For others, it was the mattress, the emergency rent payment, or the prescription medication. These small items, given in charity and passed through loving hands by a volunteer looking for the face of Christ, literally became the pivot point of a lifetime.

It is more than a slogan, more than a convenient metaphor to prompt charitable giving. The Vincentians prove day after day that pants and canned peas, not unlike the humble seed planted in good soil, bring about the kingdom of God on earth.

After all, Christ wore clothing too. And in his own words, “Whatever you did for one of these least brothers of mine, you did for me.”

To learn more about the Society of St. Vincent de Paul or to make a donation, visit svdpusa.org.

Katie Rutter is an award-winning video producer, editor, and journalist based in Bloomington, Indiana. Her article “Nuns and Nones: Connection across Generations” was the November 2020 cover story in St. Anthony Messenger.

The first step for Master Artist Mark Balma is a preliminary drawing study. The studies shown here are Sarah (above), Eve (middle), and Hagar (right).

Faith & Frescoes

Celebrating Holy Women through Art

Story by Patti Normile

Photography by Paula Laudenbach

The Umbrian town of Terni, Italy, suffered extensive damage from World War II bombing. It paid the price for being a center of armament production. Through the decades, much of the town has been restored. The Cathedral of Terni presides over the town piazza. Tourists and residents hike to view the magnificent Marmore Cascades that plummet hundreds of feet into the valley below.

Despite all the restoration efforts in Terni, one large church stood alone in need of major renovation. The Church of the Immaculate Conception peered out lifelessly across a meadow. In 2017, Don Giovanni, then pastor in the Diocese of Terni, saw potential in the church. Its very name indicated life: Immaculate Conception, life from a woman.

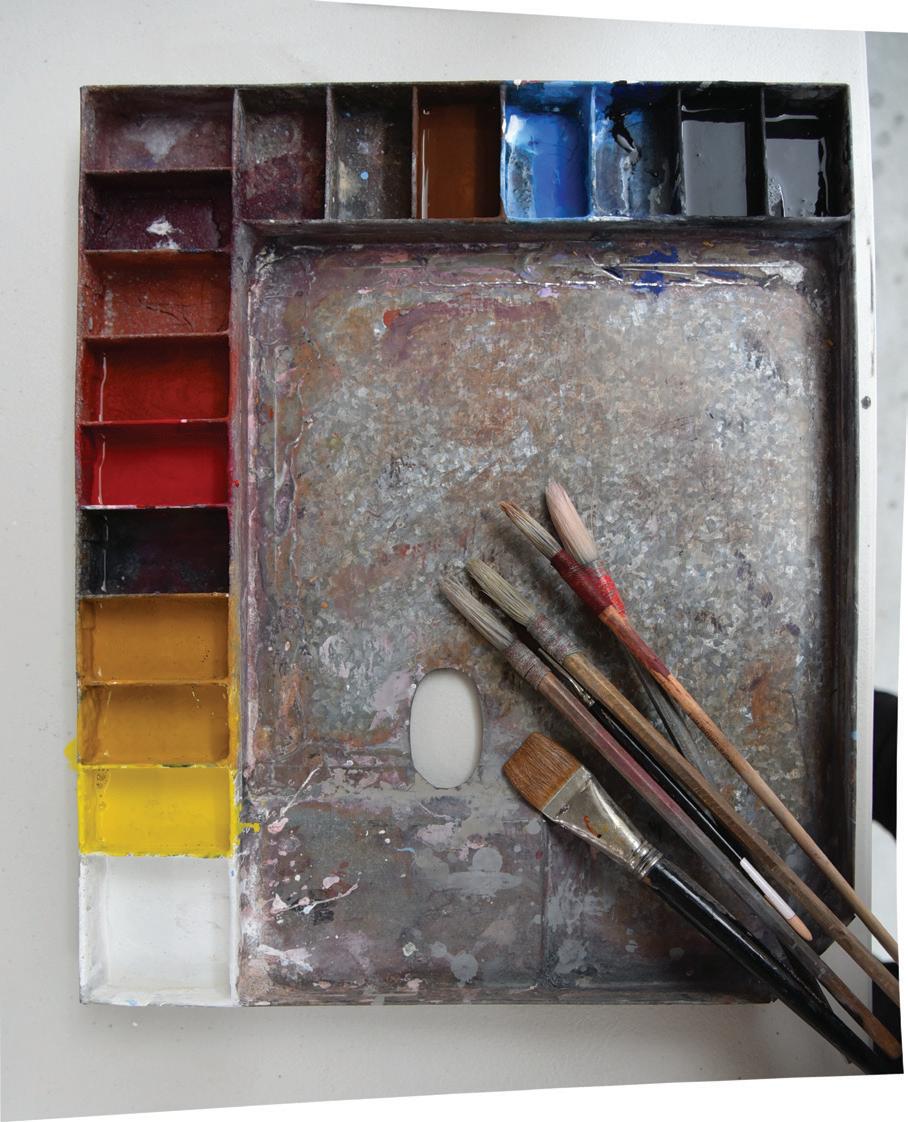

ABOVE: The Church of the Immaculate Conception in Terni, Italy, currently displays the studies until the frescoes are completed and installed. BELOW: Mark’s custom-made palette keeps the paints separated while he works atop the scaffolding.

When COVID-19 prevented artist Mark Balma from traveling to Italy to paint frescoes of holy women, he devised a novel solution: Paint them in the United States and ship them there.

Gathering parishioners, townspeople, Italian theologian Lilia Sebastiani, and other imaginative individuals, Don Giovanni experienced the birth of a plan. This church would bear witness to women whose faithfulness—as recorded in the Torah, the Bible, and the Quran—has endured through millennia. The women selected for the project have inspired, nurtured, and often suffered for their faith. What unites them is their faith in God, the Holy One, revered and worshipped in the Abrahamic religions.

The purpose of the project is to ignite discussion about what these women of faith reveal regarding the “genius of women.” This phrase comes from St. John Paul II’s 1997 book, The Genius of Women. What role does God desire that

The special material used for the canvas was made in Sweden and shipped to Minnesota. The 14’ x 19’ panels must be primed before painting can begin. The Italian brushes Mark uses are made from wild boar hair, the only material resilient enough to withstand the fresco paints. He has owned these brushes since the 1980s.

The MoZaic Building in Minneapolis, Minnesota, provided the space and lighting Mark needed to paint the Women of Faith frescoes, as well as room for others to observe art in action. The group responsible for the building is a Jewish organization, highlighting the fact that many of the women featured in the paintings are Jewish.

After priming, Mark sketches the figures with charcoal and then paints over the lines using charred grapevines, also known as “vine black,” a technique used by the masters during the Renaissance. women exercise to bring about the kingdom here on earth? For far too long the true gift of women to the life of faith and the life of the Church has been underemphasized. Attention is needed to bring into full consciousness the feminine “genius of women.”

Once the women were selected—Eve, Hagar, Sarah, Ruth, and Naomi; the woman in the Song of Songs; the Samaritan woman; Mary, the mother of Jesus; friends Martha and Mary; women disciples at the Last Supper; and Mary Magdalene—to grace 10 large (14’ x 19’) panels in the Church of the Immaculate Conception, the question arose: How would they be portrayed? The ancient and enduring medium of fresco was selected.

ENTER THE ARTIST

The fresco artist chosen to portray Women of Faith is a master of the art. Mark Balma, of Minneapolis, Minnesota, and Assisi, Italy, is known as the premier fresco artist in the world today as well as a portraiture artist. Drawn to art as a child who constantly sketched his teachers and classmates, Mark was trained in portraiture by Richard Lack, and in fresco art by Pietro Annigoni of Florence, Italy, who became his mentor when Mark was 19.

Balma creates memorable portraits in a technique created by Leonardo da Vinci. His portraiture includes five presidents, generals and government leaders, and simple street people. Balma’s portrait of John Lewis, the courageous, tireless member of the House of Representatives, hangs in the Smithsonian Gallery honoring African Americans.

But it was Balma’s talent in fresco that was needed for this project. Bringing Women of Faith to life requires a multitude of qualities in addition to superb artistic ability. Many of these qualities are revealed in Balma’s personal life: a deep spirituality, a devoted prayer life, a passion for his work, intense focus, and the strength and energy for lengthy workdays often standing on scaffolding high above open space.

Preliminary sketches of the 10 panels were complete, and sacks of plaster awaited transformation into art in Terni, according to the ancient technique of buon fresco. Then the coronavirus pandemic wrapped the world in change and fear. Balma has dual US and Italian citizenship, but transportation of materials and permission to enter Italy were not possible during the pandemic’s onset.

Balma’s alternative? He has chosen an ancient Greek form of fresco from the fifth century BC to continue with Women of Faith during the pandemic. He will create frescoes on heavy linen fabric stretched on frames, not in Italy, but in Minnesota. The panels will be completed in the MoZaic Building in Minneapolis. Balma contacted the construction

—Don Giovanni

corporation about using the space, and the response was positive and immediate. The structure, which is to be an art center, has well-lit, ample space for his work.

Paints will be created by grinding the fresco colors into an ancient recipe used throughout the Renaissance. Prayer will initiate each day’s creation. Section by section, images of women of faith will emerge. When a panel is complete, it will be removed from its frame and rolled for transport. Panels will be shipped to Terni when the pandemic loosens its grip on the world. Immaculate Conception Church will remain a place of worship as it awaits its adornments of faith.

St. Francis of Assisi was called to a lifetime of service and devotion to the Lord by words he heard from God, “Go and rebuild my church which, as you can see, is falling into ruin.” Perhaps the message of Women of Faith is this: “Go and restore faith in God, the holy one.”

BEAUTY, GRACE, AND UNDERSTANDING

Don Giovanni says of the project: “Art and beauty are two forms of communication that humans have always used. I believe these new frescoes have a unique potential to bring a message of love, peace, joy, and fullness to this and future generations. They will give beauty and a sense of completion that this building has never seen and new life to a church . . . in desperate need of repair and love.

“In the time of confusion in which we live, when old values seemed to have disappeared, we find ourselves in need of knowing more fully God’s will for our lives. We propose this study of biblical women as an attempt to reveal further the will of God.” In this place of meditation, visitors will find solace and direction as they reflect on the women who nurtured the churches of antiquity.

The frescoes are more than exquisite art. They are visible prayers that will reach from a church once destroyed by bombs into a world pleading for peace. The women’s stories expressed in Scripture and tradition offer hope and direction for living in the 21st century. Each panel contains a message

PHOTO COURTESY DON GIOVANNI

Don Giovanni (left), the driving force of the Women of Faith project, and Father Don Paolo, newly appointed parish priest, stand outside the Church of the Immaculate Conception, where the frescoes will be installed.

The faces are covered with paper to protect them from stray drops while Mark works on another area. The art of fresco painting is unforgiving: The paint dries quickly and does not allow much time for reworking. Each brush stroke must be intentional. The Women of Faith project will be the largest contemporary installation of its type since the Renaissance. Its size is comparable to that of the Sistine Chapel.

for God’s people today. In meditating on each biblical story, seekers may gain a deeper understanding of the will of God.

The project invites people of various faiths to visit Immaculate Conception Church in person, virtually, or through printed material to worship and discover their shared faith in the God of all. The faith that joins these women of Abrahamic faiths is more powerful and unitive than the differences of culture they experience. Don Giovanni expresses that hope: “Our prayer is that the images of Sarah and Hagar with Abraham will allow us to believe that an interreligious dialogue is possible between Hebrews, Christians, and Muslims.”

Patti Normile is a Secular Franciscan, retired teacher, and hospital chaplain who resides in Terrace Park, Ohio. A wife, mother, and grandmother, she is the author of several books and has written numerous articles for St. Anthony Messenger.

Watch the Artist in Action and Lend Support

While the worldwide pandemic has slowed the creation of the Women of Faith frescoes, the work is now underway. When the pandemic subsides, arrangements will be made to allow visitors to view Mark Balma in action in the MoZaic Building in Minneapolis. In addition, Mark’s team has provided a link on the Women of Faith website, WomenofFaithFrescoes.com, where interested individuals can watch the work in progress until its completion. The site also features descriptions of the women chosen, as well as videos detailing the art of buon fresco.

Creating works of fresco is an expensive endeavor. Don Giovanni has found support for Women of Faith from individuals and companies in Italy and abroad. No church or government funds are used for Women of Faith. CAF AMERICA is an organization that enables cross-border giving by Americans to validated charities and charitable projects across the world. For more information, go to CafAmerica.org.

By Phyllis Zagano

Sacred Silence

“Lent is not an intellectual exercise, but an affair of the heart,” says this author. By centering ourselves in prayerful stillness, we open ourselves up to a deeper engagement with this holy season.

In his Lenten message several years ago, Pope Francis focused on our common humanity, our common hungers, and our common needs for spiritual fulfillment. He wrote that we all face three types of hunger: material (poverty), moral (sin), and spiritual (lack of a relationship with God). Each can be healed with the Gospel, but first, Francis wrote, we must be “converted to justice, equality, simplicity, and sharing.”

We are all hungry. We are destitute and desolate in our search for what will fill us. We usually know what we want; too often we do not know what we need. Do we want fortune? Do we want fame? Do we want a better car or a better house? Do we want more friends or fewer responsibilities?

These are questions of human life. Some are, or at least become, very real needs. Others are merely distracting temptations.

The one thing we really do need is to answer them. We need to pay attention to and select among the great kaleidoscope of choices life puts before us in such a way as to fulfill our legitimate desires without disrupting our own or others’ lives. We are always choosing between and among goods, but like the little girl in the toy store whose mother says she can choose just one doll, eventually we need to kiss the other choices goodbye.

So, how do we figure out what we truly need? How do we figure out, therefore, what we really want?

I think we find an answer in silence. Not the answer—at least not immediately—but at least the method, the path we can take (each of us) toward the way to find the answer for ourselves, and for no one else.

It is about prayer. It is about stillness. It is about stillness and silence in Lent.

In many parts of the world, Lent begins in the silent time of the year. The earth is gently awakening from its winter slumber, gradually bringing forth its

remembered fullness. In other parts of the world, Lent is a time of slowing down, of increasing coolness, of moving toward the dark bright of longer nights, when the burst of dawn truly does break forth day after day, promising more, promising deeper, promising a greater silence, and, conversely, promising a greater light.

These are the days we cherish in silence as we move toward the Resurrection.

ENTERING INTO SILENCE

Lent is not an intellectual exercise, but an affair of the heart. Ash Wednesday comes around each year. We get ashes. We remember prayer, fasting, and almsgiving. We say we’ll do better at something, or not do something else at all. Whatever sin or addiction has plagued us since the turn of the year, the one we have not yet managed to get rid of despite our New Year’s resolution to somehow dislodge it at the roots, Lent presents us with another chance. But how?

We think and we think and we plot and we plan. If the use of too much Internet or salt or sleep is on our minds, like the three little pigs we huff and we puff until we blow those little houses down, unfortunately to no avail. We work away at our dependencies as if everything depends on us. It does not. Everything depends on our own dependence on God. And we cannot learn anything about that dependence by thinking and plotting and planning—by huffing and puffing.

We need to open our hearts. We need to be quiet.

But how?

Some time ago, when I was relearning how to pray for the umpteenth time, I realized that I was just plain talking too much. Everything was going on in my head. That was it. Just in my head, nowhere else. I’d built a wall between me and my emotions, a very practical thing to do if you want to maintain control over everything in life. It is not a very practical way to approach prayer, because it stifles the longings of the heart. I yearned for knowledge that I was really praying, that I was someway, somehow connecting to the God I said I loved and whom I said, at least, I wanted to follow in the way Jesus taught.

But, as I learned in graduate school, so long as I was talking— whether in class or on an oral exam— there was no way I would be questioned, especially no way I would be asked a question I could not answer.

That may work in graduate school, but it is not a smart way to pray.

LESSONS LEARNED

So here is what I have learned. Take it, or not, as you begin your own journey through Lent. Whether the ground around you is getting colder or warmer, whether the light outside is getting dimmer or brighter, I offer you the suggestion, at least, that the desire you carry in your own heart to listen to and love the Lord with all you are and have will be opened and answered if you offer first of all your own silence to the project.

That does not mean becoming a vegetable. There are many ways of being silent and many aids to doing so. Of course, if you know what keeps your mind active on thoughts other than the presence of God, you should be able to become aware of when such thoughts present themselves. I hesitate to call whatever it is a “temptation,” for it may or may not be. But there are some things in our lives—food, music, conversations—that stick a little more firmly to the surface of our minds and form a sort of coating that keeps away the silence.

I am not saying you need to give up all conversations, or music, and certainly not all food for Lent. I am saying that as we become more and more aware of our need for silence, even throughout this holy season, one or some of these choices might pop up as a bit of a barrier to silence, and therefore as a bit of a barrier to our maintaining the type of silence we need so as to be able to hear the voice of God in our hearts.

Let me give you an example. I happen to like jazz. I kid around sometimes, calling it my “liturgical music” because the syncopation and the words of some of the songs, especially the love songs, often fit my mood when I am trying to be alone at prayer. But sometimes, that very syncopation and those very words become an obstacle as they take over my mind. I think here of what is called “the Boléro effect,” the repetitive beating of a single strand of music that the French composer Maurice Ravel did on purpose. As the syncopation and words take over my mind, I find I am helpless to hear anything God might present or even to say anything to the Lord. So, sometimes—actually more than sometimes—I “give up” jazz.

Now, there is nothing wrong with jazz. For other people, for other people’s minds, the same thing might happen with Gregorian chant, or with ABBA, or with the music of the Beatles.

These are all wonderful creations, but they can each in their own way become distractions to the project at hand. Which is silence with an open heart. Which is silence with an open heart before the Lord.

This article is an excerpt from the book Sacred Silence: Daily Meditations for Lent (Franciscan Media), by Phyllis Zagano.

Phyllis Zagano is an internationally acclaimed Catholic scholar and lecturer on contemporary spirituality and women’s issues in the Church. Her books include Women Deacons: Past, Present, Future (with Gary Macy and William T. Ditewig) and Mysticism and the Spiritual Quest. Her twice-monthly column, Just Catholic, runs in the National Catholic Reporter.

To order a copy go to:

Shop.FranciscanMedia.org.

For 20% off,

use code: SAMSacred