9 minute read

Borderlines

After completing research in Srebrenica and Sarajevo, Hannah Carrese crosses the Adriatic on her way to work with refugees in Rome.

From Global Scholar to Rhodes Scholar: Hannah Carrese ’12 Sets Her Sights on Finding Solutions to Today’s Refugee Crisis

by Susan Enfield ’83

Hannah Carrese is in a hurry. Civil conflict has displaced 65.3 million people worldwide—more than after World War ll ended in 1945. At 22, Carrese is already tackling this complex, fastgrowing crisis and is eager to help remedy it.

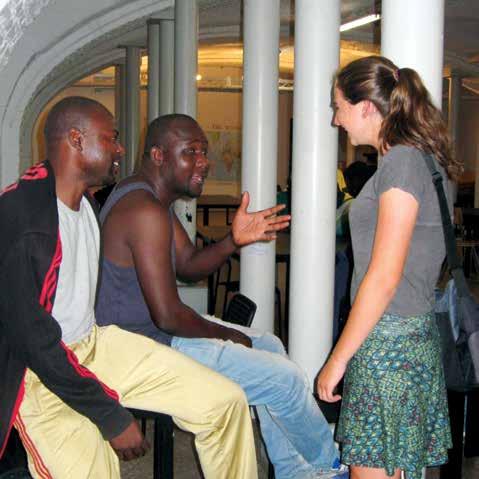

Fountain Valley School of Colorado Carrese learning the story of an Iraqi refugee in Rome

Raised in Colorado Springs by globally minded academics—her parents

are FVS Director of Global Education and English faculty Susan

Carrese P ’12, ’15 and former Air Force Academy political science

professor and Rhodes Scholar Paul Carrese—Carrese considers herself

“a world citizen with an American base.”

We caught up with Carrese on a brief U.S. visit early this year as she

headed back to Mexico City to finish a fellowship in June, followed by a

summer research tour of Central America with her mom, then postgraduate

study at Oxford on a prestigious two-year Rhodes Scholar award.

With an easygoing manner that belies laser-focused intensity, Carrese filled

us in on her ideas, current projects and plans for driving positive change on

migration and refugee policy through both academic study and

Q. How did your parents influence you? A. My parents hold a debate on citizenship each year for my mom’s Global Scholars at FVS. My dad takes the view that citizenship requires a circumscribed body politic—that the very term implies affiliation with a community that is limited in some way. My mom thinks global citizenship—the cosmopolitanism Socrates talked about ages ago—is necessary. She argues that “third-culture” kids like her—she was born in South Africa but raised mostly in the U.S.—are evidence of this possibility.

My point is: these debates filter into our life as a family. My brother, Dominic ’15, and I were just talking about this as one of our most fundamental beliefs: that people who

love each other deeply must share ideas—at times difficult ones—through conversation. This extends from families to nations. It will be special to be at Oxford this fall, partly because my parents met there and began their life’s conversation there. I’m proud and privileged to be following in my dad’s footsteps as a Rhodes Scholar, and also in my mom’s: I’ll be a student at St. Antony’s, her Oxford college. Q. At FVS, you were in the Global Scholar program your mom created for students to develop an international perspective through study and experiences. How did that help set you on your path? A. My mom has been thinking about educating for global citizenship for a long time: it’s been a family project of sorts. During my eighth grade year, we lived in India while my dad taught at Delhi University on a Fulbright. For my brother and me, this meant immersion in a school of the world. We traveled through India by train with our backpacks and books, learning by listening generously and looking closely.

This is the same kind of work she does with Global Scholars. For instance, on an interim in Israel and the West Bank with my mom and Señora [Pat] Kule, a wonderful former FVS Spanish teacher, our group learned how to engage in tough conversations. Q. What did you study at Yale? A. I studied humanities, an interdisciplinary major that encourages students to put texts and disciplines into conversation with each other. In my case, this meant pairing studies of political theory with literature. My current work in Mexico really is at the intersection of these two disciplines: I interview asylum-seekers who are politically recognized as refugees based upon the strength of their stories about their “wellfounded fear of persecution” [a key phrase from the 1967 Protocol on Refugees] in their home country. Their narratives have very real political implications. Q. What will be your focus at Oxford? A. When I was applying for the Rhodes, a mentor at Yale asked me whether I was wasting time, whether these issues were too pressing and I shouldn’t just dive in right away and act on my ideas. It’s a good question. I think it does make sense to study more; academics and action don’t preclude each other. For instance, my current project pairs research with practical humanitarian work.

With Sin Fronteras, I’m helping build a new community center in Mexico City for refugees from all over the world. It’s a place to gather and build community with English classes, lectures, clothing swaps, movies and more. It’s a newer concept in Mexico: to successfully integrate refugees, you need a sense of community. But I believe the only way to make a lasting impact with forcibly displaced peoples is by studying the policies that have led us to what I think is a political crisis. The political systems we have today are really born of political theories. At Oxford, I want to study the roots of those ideas, so I can figure out how to fix what’s gone wrong with the policies. That’s the plan, anyway.

It’s been fun to talk to FVS students about this in [history faculty] Mr. [Mike] Payne’s “Islam and the West” class and with the Global Affairs Forum.

With Sin Fronteras, I’m helping build a new community center in Mexico City for refugees from all over the world. It’s a place to gather and build community with English classes, lectures, clothing swaps, movies and more. It’s a newer concept in Mexico: to successfully integrate refugees, you need a sense of community.

Q. How is migration changing today? How are our definitions changing? A. We’re finding out all over the world how important the word refugee is. For individual asylum seekers, being recognized as a refugee may mean the difference between a new opportunity in a new country, or even life or death.

An Iraqi refugee in Colorado Springs shares photos of his home.

Q. What have you learned about migration while in Mexico? A. Mexico is a transit country for migrants coming north toward the U.S. Many are from Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala. Honduras and El Salvador have very weak political institutions, are riven by gang violence and have some of the highest murder rates in the world. In addition, many migrants in Mexico now hail from Haiti, Cuba, Africa and throughout the world.

It’s still pretty easy to pass through the southern border with Guatemala, but it’s more difficult for migrants to get through Mexico now. This is in part because the U.S. has funded a Mexican initiative called Programa Frontera Sur, which has made Mexico itself into a “vertical border.” In the same way the EU used Turkey as a holding zone for Syrian asylum seekers fleeing westward, the U.S. is doing this with Mexico and Central American asylum seekers. People who leave home are described by several words, not all of which are well understood. A migrant can be anyone who leaves their country. People who are forcibly displaced—now the largest group at more than 65 million worldwide—leave home because they have to. Many are displaced within their home country. If they cross a border, they become an asylum seeker. Asylum seekers hope to be recognized as a refugee. Per the Refugee Protocol’s definition, a refugee is a person fleeing because of a “well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, ethnicity, social group or political opinion.” There are now 21.3 million refugees worldwide, an all-time high. New issues are motivating migrants. For instance, people are fleeing because of climate change. In Honduras and El Salvador, people are leaving due to chronic, generalized violence at home. These people don’t fall under the current definition of refugee. So the question is, how does the term refugee stand up? My independent research is focused on figuring out what the word will (and should) mean in the 21st century.

Carrese listens as refugees from Congo describe their journey across the Sahara and the Mediterranean to Italy.

Q. Why is immigration such a charged issue? A. The U.S. is exceptionally good at integrating refugees and migrants. Of all the nations in the world, we are best equipped to do this work. With migrant and refugee movement increasing and sparking a rise in populist and nationalist movements in the U.S. and Europe, it has become a political crisis.

Two things: Refugees mostly settle in poor neighborhoods. The local residents are bearing the real brunt of refugee integration, which is difficult in its early stages. Also, with immigration, people react to pace of change more than to the specifics of change. And for the past 15 years, the international community has let political conflicts that lead to refugee displacement fester. The massive number of forcibly displaced people worldwide today is a result of our inaction. That refugees are moving so (relatively) quickly now suggests just how desperate they are. This means they’ll keep moving—and that we’ll keep having difficulty integrating them quickly enough.

Q. What are good ways to start shifting attitudes—and policies? A. Conversation is the beginning of change. I want to enter a conversation about the political roots of the refugee movement. We think of refugee displacement as a humanitarian problem that can be ameliorated by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).

In fact, displacement is a symptom of a deeper political crisis. It’s a crisis of both world order (state borders vs. human rights) and specific eruptions of violence, like that in Syria, which the international community no longer has the will to solve using the required political means.

Q. Where do you see yourself in a few years? A. I believe I will engage politically in some way. I may study law after Oxford, as a way of becoming fluent in the language of politics.

The time I’ve spent in Mexico has given me an understanding of the migration problem in the Americas. That’s an issue that resounds in the American West. Colorado is a really important place for me—it’s a landscape I want to return to. I want to tackle these migration issues in the American West.

Follow Carrese on her website: borderlineproject.com