23 minute read

In Search of a Legend

THE REMARKABLE STORY OF TAP RICHARDS ’92 AND HIS SEARCH FOR THE LEGENDARY MOUNTAINEER GEORGE MALLORY ON MOUNT EVEREST

by Rick Gydesen ’77

One of the most striking aspects of Fountain Valley School is how interesting our alumni are, both in terms of their backgrounds and the lives they went on to lead after they graduated. Whether I’m striking up a conversation at Alumni Weekend or reading a profile in the Bulletin, I always come away amazed by the truly remarkable life experiences so many of my fellow alums have had.

Of all the Fountain Valley stories I’ve heard, read or told myself over the past 40 years, none has astonished me more than the story of Tap Richards, a young athlete from New Mexico who went on to make history as a member of the research expedition that discovered the remains of the legendary British mountaineer George Mallory on the face of Mount Everest.

The English climber George Leigh Mallory (1886- 1924), one of mountaineering history’s most enduring icons, is credited with coining the phrase that has become part of the lingua franca of all mountain climbers. When asked by a New York Times reporter why he wanted to climb Mount Everest, Mallory replied, “Because it’s there.” But more characteristic of Mallory was his response to another reporter who asked what use there was in climbing. “None,” was the reply. For Mallory and the generations of climbers who followed him, conquering the mightiest peak of the Himalayas was simply gratification, satisfying the indomitable impulse to achieve.

For more than half a century, it has been accepted that Sir Edmund Hillary was the first Westerner to reach the summit of Mount Everest in 1951. But from the beginning, there’s been a devoted contingent of climbers who are convinced that this distinction

may belong to George Mallory, believing that it is highly likely that he and his team of British mountaineers (the British Everest Expedition) reached the summit on their third attempt 27 years earlier in June of 1924. But something went terribly wrong on that climb, and Mallory and his partner, Andrew (Sandy) Irvine vanished and were never seen again. The evidence was too scant or misleading to reach any conclusion as to whether Mallory and Irvine were lost during the ascent or descent. All that remained was the eyewitness account of a team member who sighted the two climbers at 12:50 p.m. on June 8, 1924, as they ascended an escarpment high on the final summit ridge (known as the Second Step), and then vanished into the mist.

Whether the pair actually made it to the summit has been the stuff of lore ever since. And for a devoted contingent of mountaineering buffs, the mystery has

been an outright object of obsession. As the German mountaineer Jochem Hemmleb, one of the world’s leading experts on the history of Everest expeditions, puts it: “In the world of exploration and mountaineering, the question of what happened to Mallory and Irvine was the greatest mystery yet to be resolved. So yes, if that is obsession, I plead guilty.”

Even if it could never be proven or disproved that the two reached the summit, finding the bodies of these two legendary pioneers would provide a sense of closure. In 1975, a Chinese climber named Wang Hungbao claimed to have spotted what he referred to as “English dead,” the body of an English climber in the vicinity where Mallory and Irvine were last seen, wearing old clothing that disintegrated when touched. But no photographic evidence was secured, and Wang was killed in an avalanche before he could provide any more details.

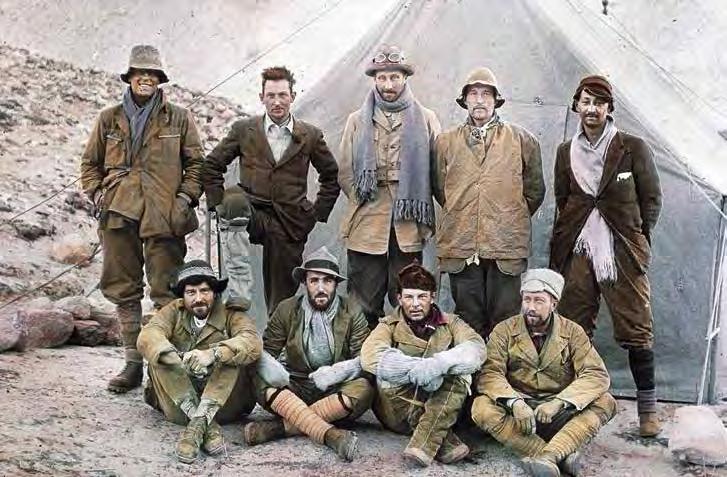

Sandy Irvine is in the back row, far left, and Mallory is next to him with his foot on the shoulder of the man seated in front of him.

So it was clear that relying on stray clues from random discoveries was not going to solve the mystery. The only way the world would find out once and for all what happened to George Mallory was to mount a specific expedition to go look for him. Hemmleb had long entertained the same thought, but it took an unsolicited inquiry from a stranger to set the idea in motion.

In 1998, Hemmleb received an email from an American named Larry Johnson, the marketing director for a small independent book publisher, who was likewise obsessed with Mallory. The two hit it off right away and struck up a daily correspondence. When Hemmleb confessed his interest in maybe doing this search himself, Johnson took the bait, and the two men began exploring the possibility of mounting an expedition of their own.

They settled on doing it the following year, which coincided with the 75th anniversary of the 1924 climb. But they needed someone with the experience and funding to pull it off. A chance perusal of a mountaineering brochure led them to Eric Simonson, a veteran mountain guide whose company, International Mountain Guides (IMG), was advertising a commercial expedition to the north side of Everest the following year, taking the same route that Mallory attempted. Simonson was intrigued, and he agreed to let the two piggyback onto his own expedition. But as the plans unfolded, Simonson decided that a dedicated expedition was required for this project, and thus the Mallory & Irvine Research Expedition was born. They spent the next few months securing underwriting for the climb, and once the British Broadcasting Corporation and WGBH/Boston’s NOVA series signed on as media sponsors, they were ready to assemble the expedition team.

Simonson’s criteria were simple. In “Ghosts of Everest,” the lavish account of the expedition published by Mountaineers Books, author William Nothdurft related

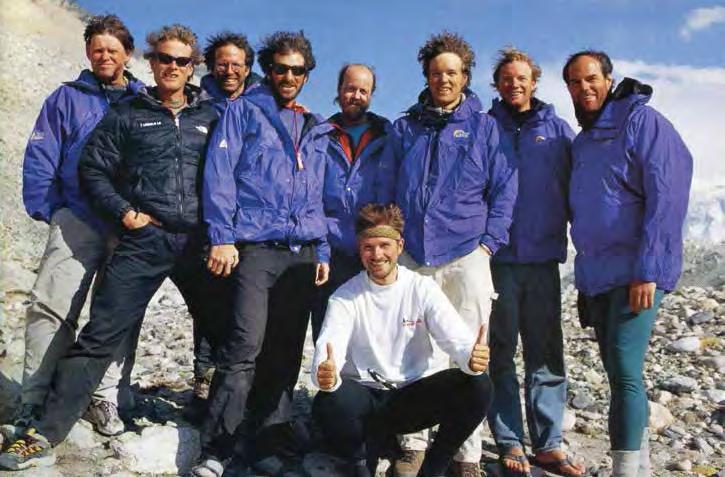

The 1999 Mallory & Irvine Research Expedition. Richards is second from right.

that Simonson was looking for “seasoned, high-altitude climbers who were even-tempered under pressure and would keep the expedition’s common goals always in mind, and who were trained to look out for the welfare of others, a characteristic critical in Everest’s dangerously unpredictable conditions.” In other words, a climber like Tap Richards.

A professional mountain guide since 1992 and based in Seattle, Richards’ guiding career has taken him to Alaska, South America, Mexico, Europe, Africa, Russia, Australia, Antarctica, Tibet and Nepal. He has made more than 100 successful summit attempts: Mount Rainier (149 times), Mt. McKinley (9), the Orizaba and Iztaccihuatl volcanoes in Mexico (11) and Mt. Whitney. He summited Everest’s neighboring peaks Cho Oyu and Ama Dablam, both twice, and in 2006 he achieved the greatest summit of all, Everest itself.

In 1999, Richards had been working for Simonson for several years leading mountain climbing expeditions for IMG in the Pacific Northwest. Impressed by his leadership skills, character and superb physical fitness, Simonson selected him and his IMG colleague Jake Norton as the Mallory & Irvine expedition’s “youngsters.” They were both 25.

The expedition set off for Kathmandu on March 18, 1999, launching an extraordinary journey that would last more than two months. It took almost six weeks of preparation (including the initial climb to the first series of base camps) before they were ready to begin their first task: to find the bodies of Mallory and Irvine.

One of Richards’ duties on the climb was setting up the various base camps as the expedition ascended the mountain. His father was a contractor, and having worked part time on his dad’s construction jobs for years came in handy when it came to turning 100 yak loads of gear and supplies into Camp III, the expedition’s advanced base camp at 21,200 feet on the North Face of Everest. As Richards reminisced, “My dad told me there’s

always something to be done on a job site. If you find yourself standing around with your hands in your pockets, then the house must be done. The same goes with [climbing] expeditions.”

An Everest climb isn’t a long weekend break from work; it requires months of preparation, and once you arrive in Nepal, several more weeks of setup are required before you’re ready to tackle the mountain. The Mallory & Irvine Research Expedition team set off from Kathmandu on March 22, and it wasn’t until the morning of May 1, almost six weeks later, that they finally reached Camp VI and the search area. After a half-hour rest, full of optimism and the thrill of anticipation, the team set out to find Mallory and Irvine.

Barely a half hour into the search, Richards and two colleagues stumbled into a graveyard of mangled, frozen bodies below the famous Yellow Band. It turns out they were all relatively contemporary climbers who had fallen from the Northeast Ridge above and had not been found. Richards recalled, “We found ourselves in a kind of collection zone for fallen climbers.” He radioed details down to Hemmleb at base camp, and was amazed how the Everest buff could identify a dead climber just by the kind of socks the person was wearing. “I wasn’t eager to get close,” Richards said. “Seeing those first few bodies was eerie, grim and humbling.”

They began their search for Mallory and Irvine in the area believed to be the last place they had been seen. But as their efforts continued to bear no fruit, one of the climbers (Conrad Anker) decided to follow his intuition and look lower. Perhaps the two mountaineers had fallen?

Miraculously, after just an hour and a half into a search on a vast section of the North Face, intuition paid off: at 11:45 a.m. on May 1, 1999, at 26,770 feet above sea level, Anker spotted an odd patch of white on a steep slope, which turned out to be the alabaster-white remains of a Western climber wearing vintage clothing and partially encased in frozen rock and gravel. The rest of the team was radioed and eventually assembled around the body, which was lying face down, fully extended, and partially exposed on the rocky slope. Richards and the team stood or kneeled around the ancient body, speechless.

At first they were convinced it was Andrew Irvine, as it had to be the less experienced of the two who would have fallen (several bones were broken, and the body’s posture clearly indicated a fall from a great height). Richards, who had studied and trained in archaeology, began to carefully clear debris from around the The last photo ever taken of Mallory and Irvine

embedded body, painstakingly separating layers of clothing. Turning over a section of shirt collar, there it was: a laundry label that read G. Mallory. More shirt tags were revealed, all bearing the same name. In awe of being in the great man’s presence, it took a while for the reality to sink in.

As Richards’ colleague Jake Norton remembered, “It had always been understood that George Mallory was infallible. He didn’t fall, he couldn’t fall. It was a shock to discover that he was fallible.”

With time ticking away until they had to descend to base camp, the team worked quickly. They removed any surviving artifacts from the body: clothing, an altimeter, Mallory’s sun goggles, pencils, notes and letters wrapped in a handkerchief, scissors, a matchbox, a tube of petroleum jelly, a safety pin and even a small tin of meat lozenges. They were anxious to take everything, especially any evidence confirming whether Mallory and Irvine reached the summit or not, because if something was left behind, “people would keep coming back and disturbing him again.”

They also documented the body photographically, which stirred up quite a controversy later after the photographs were published, from reverent climbers who felt it was disrespectful. Much of that outrage was probably due to the body being so well preserved. Had they discovered a pile of bones, it would have gone unremarked upon. In a post-expedition interview, Richards explained: “The publishing of the pictures of Mallory has been controversial and even complicated at times. We do have a responsibility to report our discovery accurately and thoroughly. As this great mystery of Mallory and Irvine is more than just a story or historic event, it’s of utmost importance not to withhold information about our findings. Death is obviously not pleasant, but it is something that we can all count on happening to us, our loved ones and our friends. I believe that our society can only benefit from confronting it, rather than harboring it and not understanding it.”

After rescuing every artifact they could find, the team gave Mallory a proper burial, carefully covering him with rocks. Andy Politz recited a Church of England committal service. As Norton reminisced, “I don’t think any of us wanted to leave him. He was so impressive to be with, even in death.”

The most important item Richards and the team were hoping to find was the holy grail of this enduring mystery: the collapsible Kodak Vestpocket camera Howard Somervell loaned to Mallory before the climb. Had he and Irvine made the summit, they would have taken pictures, and the film (perfectly preserved by the cold) could have been developed today, providing the answer to the riddle that had plagued so many Everest enthusiasts for three quarters of a century. But alas, they never found the camera. Nor, in fact, did they find Irvine, who they realized was the Englishman spotted by Wang Hungbao on his own ill-fated climb in 1975. Perhaps Mallory had given the camera to Irvine before they started their descent. Unless a future mountaineer happens to spot something shiny amongst the rocks, and it turns out to be the camera, we’ll never know.

A few days later, Richards found one of Mallory’s 1924 oxygen bottles near the famous First Step, proving that he and Irvine had been all the way up on the final ridge headed to the summit. Yet, as tantalizing a clue as this was, it still didn’t conclusively answer the question.

Richards, front, and Jake Norton on Everest in 1999. A week later, the team set out to accomplish the final task of their research: to prove whether it was possible to even reach the summit via the route attempted by the 1924 expedition. So on May 12, the expedition’s Summit Team returned to the North Face to retrace Mallory and Irvine’s steps and reach the summit themselves.

Two of the team members, Conrad Anker and Dave Hahn, did reach the top of the world at 2:50 p.m. on May 17, proving that this route was indeed feasible. But Richards and his mate Jake Norton turned back before the Second Step. One of the leading causes of fatalities on Everest is waiting too late in the day to begin a safe descent, known as “turn around time,” that moment when an Everest climber must abort the climb and descend whether the summit has been reached or not. It’s one of the most agonizing moments in a mountain climber’s life. Richards and Norton felt strong that day, but years of experience and intuition made them wary of the weather, and aware of the likelihood that their oxygen supply would run out if they climbed any higher.

Plus, Richards still had the memory of those dead climbers from the doomed 1996 climb in mind, who died because they most likely waited too long to descend. As he explained, “The vibes just didn’t feel right. At the age of 25, I was pretty sure I hadn’t done everything in life that I wanted.” As Nothdurft reasons in Ghosts of Everest, it was a remarkably level-headed decision for two young climbers who could have so easily been swept up by summit fever at that point. Simonson told the two climbers they were in good company. Even the great Mallory himself had to make that terrible decision, having been “rebuffed by the mountain several times.”

“You guys are young; you’ll get another chance,” Simonson consoled.

The team arrived back in Kathmandu on May 23, and the last of the crew flew home on May 27.

So did Mallory and Irvine make the summit or not? As it has been for almost a century now, opinion remains divided. Extensive forensics on the artifacts Richards and the team brought back cleared up a lot of speculation, but in the end were still inconclusive. For instance, Mallory said he would place a photograph of his wife Ruth on the summit. The photo wasn’t found among the many artifacts on his body, so where is it if not at the summit? No one can say for sure.

But if it’s any consolation, the expedition team’s research did answer one thing definitively: George Mallory and Sandy Irvine may or may not have reached the summit, but they clearly made it farther than anyone else before them. Much higher, in fact.

What does Richards think? In an interview a few years later, he offered his take: “I believe they perished before they reached the summit. I believe Irvine turned around with Mallory making a gallant solo effort near the summit and perhaps falling while climbing the Second Step or trying to skirt around it. From what I know of the Second Step, I don’t think they could have climbed it due to their limited oxygen supply. Also, attempting it as a soloist—it would’ve been more difficult without having someone there to belay.”

So the mystery as to whether Mallory was, in fact, the first person to scale the ultimate summit appears destined to remain lost on the frigid North Slope of Mount Everest.

But perhaps knowing the answer isn’t the point. Nothdurft concludes Ghosts of Everest by suggesting that solving the mystery may not matter anyway.

“What matters is the scale of Mallory and Irvine’s achievement given the resources available to them, and their astonishing strength and grit. Their level of passion and determination, their fierceness of desire, astonishes us yet today—a purity of purpose, an unwavering commitment and in an odd way, invincibility.”

As alluring as the myth of Mallory may be, what attracts devoted climbers like Richards to the man is that he is not a myth after all, but rather, “a vivid, almost luminous reality.”

Return to Everest and More History Made

As disappointed as Richards was to not reach the top of Everest himself, he was to have another chance to scale that elusive summit. In May of 2001, the Mallory and Irvine team reconvened and launched a second expedition to Nepal to continue searching the North Face of Everest for more clues, in the hope of solving the ultimate mystery of whether the duo made the summit or not. The team was also hoping to find the remains of Sandy Irvine, who remained lost [as of this writing, Irvine has still not been found]. Richards was also wishing to make the summit himself.

But once again, fate intervened. Richards and his team encountered an expedition of five imperiled Russian climbers who had been stranded overnight on the North Ridge. Partially blind from cerebral edema, suffering from frostbite and unable to walk, the Russians faced certain death at an altitude where only a handful have survived. Although they were just a few hundred feet before the summit, Richards and his colleagues gave up their own bid to the top in order to save the five Russians. While they administered food, water, drugs and oxygen to the nearcomatose climbers, other mountaineers continued past them on their way to the summit (and into the history books), which must have made their disappointment all the more acute.

In other words, it was another one of those beyond-discouraging (even heartbreaking) “turn around” moments that all Everest mountaineers face. But Richards’ selfless conduct was a testament to that depth of character that impressed faculty years ago at Fountain Valley School.

After the rescue, Richards said he would make the same decision again, but had mixed feelings about returning to Everest. He still wanted to prove he could reach the summit, “because in my heart, I believe I could have.” Richards knew that saving four lives (one Russian perished while descending) was more difficult and dangerous than bagging the summit. But as he ruefully observed, “No one gives you credit when you’re 500 feet short.”

His boss Eric Simonson begged to differ. “I was super proud of what Dave, Andy, Tap and Jason had accomplished. They put their personal goals on the back burner and saved four out of five people with virtually no assistance. I was also bummed that they didn’t get to make the top, knowing how hard they had worked. I guess that’s just the way it goes; If you don’t like that uncertainty, you shouldn’t be here.”

The international climbing community was also impressed. In February of 2002, at their 100th anniversary meeting in Snowbird, the American Alpine Club presented its David A. Sowles Memorial Award to Richards, Jason Tanguay, Dave Hahn, Andy Politz, Lobsang Temba Sherpa and Phurba Tashi Sherpa for their unselfish devotion in the heroic rescue of the five imperiled climbers.

Although the 2001 expedition came back emptyhanded as far as any further Mallory discoveries, in the end, the usually pitiless Everest gods must have smiled upon them, because it turns out Richards and his mates made climbing history after all with their selfless act of kindness. Hemmleb, their colleague from the Mallory expedition, explained the significance of the team’s success: “The rescue—the highest ever on the Northeast Ridge—destroyed the established belief that climbers couldn’t be saved at such altitudes unless they could walk on their own. It’s still high risk, and it’s not certain, but it’s possible.”

Only cooperative weather and the presence of a strong, experienced, well-equipped team willing to sacrifice their own ambitions kept tragedy at bay. environments and appreciate the remarkable adventure and all it took to get there. A few constants do exist in the Everest experience—the challenge is still tremendous, and the people of Tibet and Nepal are some of the most magnificent on the globe. I’m increasingly grateful for the opportunity to experience the culture of this Everest era. That said, you can’t but help romanticize the high experiential currency of the early pioneer expeditions. They were simply a tougher breed than those of us attempting Everest in the modern era. The fact they made it to the top of the world with nothing but two strong legs, wearing little more than tweed jackets and two layers of silk, was remarkable in itself.” Richards on Everest summit, 2006

The 100th anniversary of the 1924 British Everest Expedition is only eight years away. It will be intriguing to see if the ghosts of Everest will lure a new generation of climbers and explorers.

Whether George Mallory made history or not we’ll probably never know. But we do know that Richards’ patience, dedication and unwavering determination finally paid off: after five visits to the mountain, Richards entered the mountaineering pantheon himself by reaching the summit of Mount Everest in 2006. But in true mountaineering fashion, he looks back on that remarkable achievement in a more philosophical way.

“The real success of any mountain climb isn’t just reaching the top of the mountain, but the adventure involved in getting there,” Richards explains. “Especially a place like Mount Everest. We have no business being there, so the real measure of success is simply having the opportunity to visit the spectacular mountain

Tap Today

Now that Richards has a family, he has “shifted gears,” as he puts it. Two years ago, he left his career as a professional mountain guide behind, moved his family from Seattle to Woodside, Calif., and is now pursuing his other passion, building and woodworking.

“Guiding is an all-consuming experience, and I found being away on long climbs meant I was missing out on the chance to see my daughter grow up,” he says. Although the construction company he started keeps him more than busy, Richards still has a thirst for climbing. “Part of my responsibility in giving back is to provide my daughter with the opportunities for adventure and time in the mountains.”

Reflecting on his mountaineering and the world today, Richards says: “We continue to develop a convenience-based culture, creating an environment where we eschew challenge and instead speed through experiences that have potential to offer rich and compelling experiences. When you are out in the elements, you experience the world differently. When you push yourself physically, you strengthen and fuel your mind. Put the two together and you encounter the space to live out the purest moments of your life.”

Tap @ FVS

A native of New Mexico, Richards attended Fountain Valley School during his junior and senior years. His student file indicates that he was a superb athlete, excelling in hockey, soccer and lacrosse. A gifted photographer, he was the recipient of the School’s Photography Award at graduation. Richards was exceptionally well liked by his peers and teachers, who described him as “a positive and easygoing young man, well-adjusted socially with a large circle of friends.” Perhaps the greatest tribute to his character came from his adviser, Marc Trister, who wrote in May of 1992: “In a day when so many adolescents struggle with moral issues, I have always been impressed with Tap’s sense of justice and his deep sense of honesty.” But it was Richards’ aptitude for the outdoors that not only set him apart, but launched him on his future life journey. Having grown up with the ski slopes of Taos and Aspen as his backyard, his thirst for the outdoors and adventure had been a defining aspect of his life. So it’s no surprise that when he left Fountain Valley, he chose mountaineering as a profession. He counts Rob Gustke P ’16, ’18, FVS’s veteran science teacher, swim coach and outdoor education guru, as one of the most inspiring influences in his young life. In his evaluation following an Interim trip to Yosemite, Gustke describes Richards as “a marvelously skilled and very fit mountaineer with the potential to be a very strong leader. Tap is a well-rounded lad, strong of limb, well skilled, appreciative of the environment and willing to assume leadership. He was a huge factor in our group’s success.”

Richards reflects on his FVS experience as “a vibrant landscape illuminated by a rich experiential education program and meaningful student/teacher relationships. There was real motivation in being part of a community of unique, courageous individuals with a shared commitment to take on the academic and social challenges.”

Richards’ native talent for leadership and those strong limbs served him well seven years later when he embarked on the adventure of a lifetime, joining an elite team of seasoned mountaineers on the frigid slopes of Mount Everest to search for the long-lost body of George Mallory.