47 minute read

Bottles Dug in 2024: Digging a Digger’s Collection

While I love bitters, flasks, cures, and local bottles (like many of my fellow collectors), my collection is more a diverse mix of what our Victorian ancestors used in their day-to-day lives and decided to throw away over a century ago. I’m a passionate digger of antique bottles, driven by the thrill of discovering an artifact conceived of and designed by a business, hand-made by skillful glassmaking artisans, sold by an area proprietor, then consumed and thrown away by a local citizen, who never dreamt that someone would be digging through their trash well over 100 years in the future. It took that chain of people and events for these bottles I’m digging to be entombed under up to eight feet of coal ash, waiting for me to discover them. This, for me, creates a spiritual connection to these beautiful, handcrafted works of art.

Put together over 55 years of digging, my collection is an eclectic mix of whiskey, beer, bitters, soda, drugstore, patent medicine, ink, mineral water, and food bottles, as well as fruit jars, insulators, stoneware jugs, pottery bottles, elaborately stenciled pot lids, and more. Many of these objects I would not have sought out and purchased at a bottle show or online auction, but once I’ve dug something interesting that I don’t have, the bond has been established, and it’s going into the “Bottle Room.”

Starting the Year Off in Style

It was 8:30 am, Friday, April 26, 2024. I had just touched base with my digging buddy and high school friend, Bob Renzi, and we were set for a 9 am rendezvous at an early 1900s ash dump that had been hit hard over the years. While the dump produces a lot of machine-made age bottles, it is also famous for its “late throws,” when someone in the 1920s to 1930s was cleaning out stoneware jugs, Saratogas and other cool 1800s stuff out of their basement, shed or attic. We had scouted the dump two days before and had each managed to locate undug areas. We thus had a good start on our holes and expected our efforts would pay off today. Furthermore, a high-pressure front was hanging on for another day, resulting in a forecast of crystal-clear weather in the low 60s—perfect for digging.

Bob and I had dug together in our high school days and shortly thereafter, but while my OCD drive for digging and collecting continued unabated in the intervening decades, Bob had taken a break from the hobby while he got married, raised a family, and taught high school music for 40 years. Bob still has all his bottles from the old days, though, and now that he’s retired, he’s eager to add some exciting discoveries to his collection.

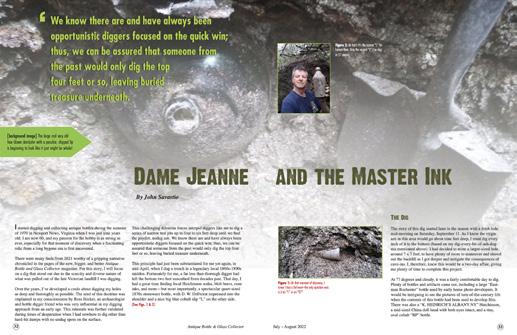

This dump goes deep, so there’s no realistic expectation to hit the bottom without the use of mechanized equipment. However, to maximize our chances of taking home good stuff, I encourage my fellow diggers to dig as deep as safely possible. For me, this

By John Savastio

means going eight to nine feet deep. This credo has paid off for me numerous times, with my best finds often discovered at the very bottom of my cavernous holes.

Beware: Poison

Some common milk bottles and 1920s Coke bottles, worth keeping for sale, were uncovered on the way down, but nothing worthy of being displayed on the Bottle Room shelves. It was around noon when I reached my self-imposed depth and began to use my three-foot-long chipping tool to dig 18 inches or so into each side of the hole, working my way up from the bottom. About a half-hour into picking at the bottom layer, I was on the side of the hole facing the trail when I noticed that my last stab at the virgin ash had revealed a three-inch blue corker on its side. Ah, it looks like a “Bromo,” I was thinking when my accursed phone rang loudly into my Bluetooth, simultaneously startling and irritating the hell out of me. Thankfully, it was an 800 number I could ignore. Getting back to business, I quickly pulled out the bottle and was thrilled to see it was three-sided with hobnailed corners. “Poison!” I cried. My first thought was that it was a “Sharp and Dohme.” I hurriedly rubbed the ash off and saw “TRILOIDS”— ”Yes!” I yelled. Although I’d never dug one, I knew the bottle and was 90% sure it was embossed “POISON,” which was confirmed a few seconds later when I wiped the ash off the next panel. I also loved the triangular shape, hobnailed corners, and seeing the word Poison so boldly embossed. While it’s a corker, it’s also an ABM (Automatic Bottle Machine), so it was probably manufactured between 1910 and 1925. I shouted out to Bob that I’d found a very cool three-sided poison and put it in my pocket. Bob was kind enough to jump out of his hole and record the moment. [Photo 1]

Although this was the first Triloids poison I’d dug, I recognized the bottle, as they are fairly common. A little internet research revealed that this product was manufactured by William R. Warner & Co., likely between 1908 and 1920. Triloids was a well-known brand of mercury bichloride, which was used at the time as a topical disinfec- tant. Per Wikipedia: “Mercury chloride (or mercury bichloride), historically also known as sulema or corrosive sublimate, is the inorganic chemical compound of mercury and chlorine with the formula HgCl2, used as a laboratory reagent. It is a white crystalline solid and a molecular compound that is very toxic to humans. Once used as a treatment for syphilis, it is no longer used for medicinal purposes because of mercury toxicity and the availability of superior treatments.” Hmm, it was a treatment for syphilis in the early 1900s and a fairly common bottle. Oh my.

I found a few variations of the bottle online. There is one that replaces the embossed copy “TRILOIDS” with “POISON” so that Poison is embossed on two sides with the third side blank. There is also a scarce four-inch-size Triloids and a very rare five-inch size. A five-inch Triloids recently sold for about $1,700 on eBay! Triloids also can be found in cornflower blue glass.

William R. Warner opened a drug store in Philadelphia in 1856 and soon invented a tablet-coating process that allowed medicine to be encased in a sugar shell. In 1886, Warner gave up his retail pharmacy business and began drug manufacturing under the name William R. Warner & Co. and later acquired several other patent medicine businesses. He later relocated the company to New York and, following mergers, changed the name to Warner-Hudnut, then to Warner-Lambert. Today, it is known as Pfizer.

Here Boy!

As I continued to chip away at each side of the hole from the bottom up, I found a few local milk bottles, but nothing too exciting. About an hour later, as the backfill in the hole had raised its depth to about five feet deep, I decided it would be more efficient (and comfortable) to stand up and chip away from top to bottom. It was at this same time that Bob decided to take a break and watch me for a while. His timing was good. After just a few minutes, at about three feet deep and on the side to the right where I’d found the Triloids, my pick tool suddenly and unexpectedly pried out a heavy light-yellow-glazed stoneware bowl, about five inches wide and three inches high, that landed on top of my boots. Well, this is an oddity, I thought as I bent over to examine the mysterious artifact. With some hope and excitement, I picked up the heavy bowl from atop my boots, wiped off the ash, and was excited to see the word “DOG” in a medium brown semi-fancy script lettering glazed on the side. [Photo 2] I’d never seen anything like it and thought, “Very cool, now I have two good finds for the day!” This unusual piece would be a nice addition to the collection.

While searching for similar stoneware dog bowls for sale online, I soon discovered that they were made in various sizes by Robinson Ransbottom Pottery (RRP) in the early 1900s. RRP was founded by Frank Ransbottom and his brother in 1900 in Roseville, Ohio. Roseville was a hotspot for quality stoneware during this time period, and the company grew and thrived. According to collectors, the earlier pieces are not marked on the base, while the later ones are. The later pieces I saw online, while similar in look, were indeed marked “RRP Roseville, O USA” or something similar. They are not terribly scarce but are in demand due to collector interest. I also saw some marked “KITTY.” The base of my dog bowl is unmarked and unglazed. My bowl also has some white glaze that was splattered on the side during manufacture, making it unique and a bit more interesting as detailed in Photo 2.

Seal the Deal

About 15 minutes later, with my hole more filled in, I was now about elbow deep and digging the same side where I’d just dug the dog bowl. I was leaning over the edge and cutting downward, just a foot from the top, when my chipping tool abruptly pried out a large (nine-inch), ovoid, amber, turn-mold corker. I recognized the ovoid shape, so I knew right away to check for the seal on the shoulder that would verify my suspicions. Sure enough, clear as the 60-degree mild day we were enjoying, the seal was there and embossed as I expected, “PAUL JONES WHISKEY LOUISVILLE, KY.” [Photo 3]

Photo 3] Author with “Paul Jones bottle seeing the light of day for the first time in 100 years.

[Photo 4] Close up of the “Paul Jones Whiskey” seal showing the smudged seal as if the glassmaker used a scraper to attach it to the bottle.

This must have been a damn good product because these bottles are quite common. That said, in 54 years of active digging, this was just the second one I can recall finding. I also remembered my rapscallion friend, Scott, digging one in the yucky mucky Phoebus, Virginia dump in the early 1970s and me being jealous. It was cool to find one now. I told myself that if it cleaned up well, I might keep it.

A few hours later, the holes were filled in, and I was on my way home, quite pleased with my day. I soaked the haul of bottles in a gallon bucket overnight and cleaned them the next day. I was very happy to see that the “Triloids Poison” was perfect. There was no stain or damage, and I could see it glow on my new shelves, backlit with 5,000-watt bulbs. I next cleaned the Paul Jones. While not quite in perfect condition, it was very close, and it was remarkably clean. I also noticed that the glass comprising the applied seal was smudged on the lower right side as if a flat-edged scraper tool had been used to press it down on that side. [Photo 4] I had not recalled seeing that before on a Paul Jones (or on any sealed bottle, for that matter). Google searches revealed several examples, all of which had perfect seals. This little bit of unusual crudeness, the excellent condition of the bottle, and its attractive red-amber color convinced me this one was a keeper.

Now that the Paul Jones bottle would make it into the hallowed Bottle Room, I needed to get some history on this relic. A webpage at Sipping History.com, titled History of Four Roses, provides a brief background on Paul Jones bottles and the Four Roses brand that followed. Note that the labels on Paul Jones sealed bottles indicate they were a “Pure Rye” whiskey, not the Four Roses brand for which the company was also famous.

“Paul was born in Lynchburg, Virginia, in 1840. Paul went to fight in the Civil War for the Confederate Army from 1863 to 1865 and earned the rank of lieutenant. In 1864, he fought alongside his brother, Warner, under General Robert E. Lee’s command, helping to defend Atlanta, Georgia. In the efforts, Warner was killed during the Battle of Atlanta. After the South surrendered and the war was over, Paul returned to his home in Virginia only to find it dismantled and destroyed from the years of war. Paul and his father made the decision to relocate to Atlanta. Together, they opened a grocery store and distribution center. Here near Atlanta, Paul began producing whiskey under the Paul Jones Company. In 1884, with the laws in Georgia tightening on the sale of alcohol, Paul once again relocated, but this time to Main Street in Louisville, Kentucky, on Whiskey Row. By this time, his father, Paul Sr., had already passed away. Paul Jr. had the Four Roses name trademarked in 1888 and then, in 1889, purchased the J.G. Mattingly Distillery at an auction. Paul was able to take possession of the distillery on Wednesday, February 12, 1890, and just a couple of weeks later, on Thursday, February 27, he began operating it. Paul Jones’ brands that he produced at the distillery included Jones Four Star, Four Roses, West End, Old Cabinet, Old Cabinet Rye, and Paul Jones (my sealed bottle). Paul Jones Jr. passed away in 1895 from Bright’s disease. His nephew Lawrence inherited the distillery.”

The Paul Jones seal bottles, though common, are very distinctive and set apart from contemporary bottles by their lovely ovoid form and the uncommon and appealing seal on their shoulder. And, as stated earlier, I was delighted with the mashed-up and malformed seal on my bottle, which distinguished it from all other Paul Jones bottles I’ve seen. This led me to ponder on exactly how the seals were applied to bottles and what could have led to the disfiguration of the seal on my bottle.

Per Wikipedia, in an article titled Sealed Bottles, “Sealed bottles have an applied glass seal on the shoulder or side of the bottle. The seal is a molten blob of glass that has been stamped with an embossed symbol, name, or initials, and often it includes a date. Collectors of bottles sometimes refer to them as applied seals, blob seals, or prunt seals.”

In a December 9, 2012, Peachridge Glass website article titled David Jackson and his Applied Seal Bottles, David provides more information on how seals were applied to bottles. “There is an additional method of embossed labeling which was used in the 17th century and continued into the 19th century. That method involves the use of a slug or glob of molten glass added to the outside of the bottle. After the bottle is formed but still hot, a hot glass slug is placed on the side of the bottle, usually on the shoulder or high on the side, and then formed flat against the bottle using a tool inscribed with letters or a symbol. This produces a round or oval glass form attached to the bottle, with the desired words or symbol permanently visible. These embossed slugs are referred to as seals or applied seals. The application of the seal is permanent to the bottle and cannot be removed without damaging the bottle.”

While this information provides a sense of how seals were made and applied to a bottle, it does not give the detail I was hoping to find. The above states the seal was “formed flat against the bottle with a tool that is inscribed with letters or a symbol.” This is very vague. In the case of my bottle, I envision that somehow, when this tool applied the seal to the bottle—perhaps by an inexperienced worker on his first day—it was not fully attached. Thus, another tool, perhaps a stainless-steel flat scraper, was used by this rookie to roughly and crudely smush the protruding right lower side of the seal to the bottle, thereby leaving me with this gift of a Paul Jones bottle with a very distinctive, contorted seal.

Memorial Day Madness

On Memorial Day, Americans honor the many thousands of brave soldiers who have fought for their country, helping to ensure that the democratic freedoms we have enjoyed for two and a half centuries continue to endure. It is also a holiday, and as such, I took advantage of my freedom from a day at work to enjoy a day of digging at my designated spot, which has been so productive for me over the last 10 years. It was day two for me, digging a hole that I had started three days earlier.

The Age of Alcohol

As someone who is fascinated with history, I get hands-on insight into the lives of Victorian Americans when I dig in old ash dumps. One thing that is evident is that the ratio of whiskey and beer bottles to food bottles is higher than would be expected (compared to our modern era). Per a Boston University article published at the 100th anniversary of prohibition, “The Prohibition movement began in the early 1800s based on noble ideas such as boosting savings, reducing domestic violence, and improving family life. At the time, alcohol usage was soaring in the United States. Some estimates by alcohol opponents put consumption at three times what it is today.” Thus, it’s understandable why the temperance movement began and led to the 18th Amendment to the US Constitution, which established the prohibition of alcohol in the United States. This also explains the high percentage of bottles containing alcohol in this late 1800s to early 1900s dump. it will be one of these scarce and more coveted sorts. I had the bottle out of the earth and in my hands in short order, and I was excited and hopeful as I felt the embossing on the underside in the center of the bottle. Quickly flipping it over and wiping off the ash, I was delighted to read within the slug plate, “PROPPER & SCHULHOF,” “1158 1st AVE 1210 1st AVE,” “421 E 72nd ST NEW YORK,” and along the top of the shoulder, “FULL MEASURE 1/2 PINT.” [Photo 5] I loved that it had three addresses embossed on the bottle. According to Matty Birittieri, an expert in New York strap-sided flasks, whom I later called on the way home, this company was in business from 1905 to 1918. Manny also provided a 1914 New York City directory entry, “Propper Edward & Co. (Leo & Edward Propper & Frederick W. Schulhof) 1210. 1st av.,” “Propper & Schulhof. (Leo & Edward Propper & Frederick W. Schulhof) 1158, 1st av.” Based on the age of other bottles in the dump, I’d venture that this bottle is in the 1905 to 1908 range. Perhaps by 1914, the 421 East 72nd St address was no longer in use. I could find no records of this bottle for sale, nor did I see it posted anywhere, so it may be scarce.

The abundance of the “Bromo-Seltzer” bottles in these turn-of-the-century ash dumps is another testament to the alcohol issues this country was experiencing. Known as the “hangover cure,” Bromo-Seltzer was (and is) a headache and indigestion/heartburn remedy invented in 1888 by Isaac E. Emerson and produced in Baltimore, Maryland. Its first formulation contained sodium bromide, a tranquilizer that turned out to be toxic and deadly. Bromo-Seltzer responded by reformulating its product with safer painkillers that contained less or no sodium bromide. The alcohol-consuming public forgave them, and sales continued to be strong.

As stated, it was day two in my hole, and by late morning, I’d already dug roughly a dozen common whiskey bottles from this pit (as well as a handful of Bromos). These whiskies are mostly slick cylinders and strap-sided flasks that came in half-pint, pint, and quart sizes and are typically embossed with “GUARANTEED,” “REGISTERED,” or “WARRANTED FLASK” on the shoulder. Sometimes, there is a blank slug plug plate in the center. It was a difficult hole. I was digging between the roots of two large, side-byside trees, doing my best not to damage the roots. Additionally, this section of the dump, located near the landowner’s garage, is heavier in industrial ash; however, it has a few layers of household trash, including one approximately eight inches thick at a depth of five feet.

It was just before 11 am, and I was about eight feet deep in the hole, on my hands and knees, chipping into the eight-inch-thick trash layer, when the bottom of a half-pint strap-sided flask was revealed to me. Even though 90% of the strap-sided flasks dug in our local ash dumps are the common type described above, one in ten or so have an embossed slug plate, and I can’t help but hope and pray that each time I come across one,

Just 15 minutes later, I was gently chipping into the same eight-inch trash layer, five feet deep in my pit, when another half-pint, strap-sided flask was revealed. Based on my 90% common, with no embossed slug plate experience for these bottles, the chances that this one would also have distinct embossing by the proprietor were infinitesimal. With expectations set low, I soon had the bottle out of the ash in my hands and wiped off the dirt. I was gobsmacked when I saw that this one, too, had an embossed slug plate! Wow, not only two in one day but two within 15 minutes of each other! This new bottle read, “FROELICH’S WINE & LIQUOR STORE, 215 STATE ST SCHENECTADY NY, REGISTERED FULL 1/2 PINT.” [Photo 6] According to Roy Topka’s book, Old Schenectady Bottles, Froelich’s was listed in the Schenectady directories for only one year, 1907, and is considered scarce.

A Mold vs. B Mold

Thirty minutes later, the eight-inch trash layer had played out, motivating me to make a 180-degree switch, moving to the landowner’s yard side of my hole. To my delight, I soon discovered a pocket of household trash, approximately four feet deep and two feet wide. At around noon, my pick revealed what looked like the back of an amber half-pint whiskey flask! Could this be my third slug plate embossed half-pint whiskey flask discovered in just one day? Moments later, this speculation ended when my chipping uncovered a blob top, and it was now clear the bottle was straight-sided and not tapered like a flask. Oh my god, I had a Warner’s!

As it had a blob top and not a double-applied collar or medicine top, I knew it could not be a half-pint

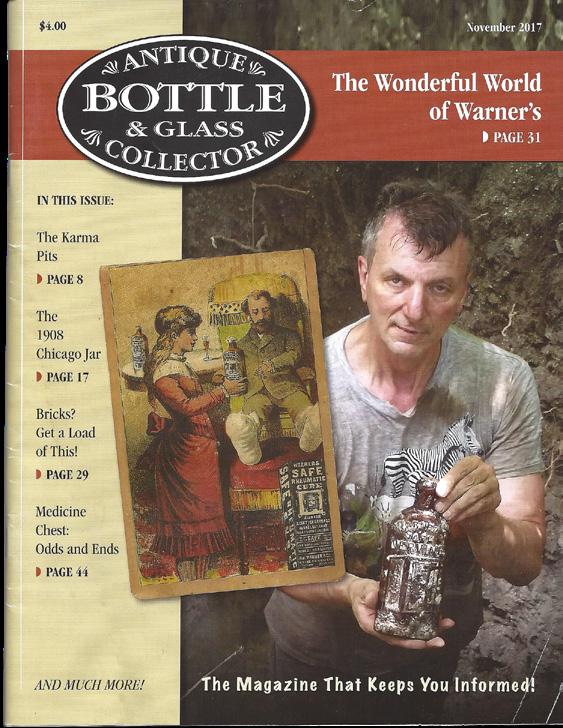

“Warner’s Safe Bitters,” one of the rarest and most coveted of all Warner’s bottles and one of the top bottles on my most-wanted-to-dig list. My second thought was it might be a “Nervine.” I had dug a pint-size Nervine in this dump in 2016 and would love to dig the half-pint Nervine to go with it. (cover of November 2017 Antique Bottle & Glass Collector) [Photo 7]

And yes, there was a third wish going through my mind. Six years earlier, in the summer of 2018, in this very same permission dump, I had dug a half-pint “Warner’s Safe Cure” with a “B” embossed in the little round indentation on the base (See Collecting a Potpourri of Dug Bottles, Part 2, Antique Bottle & Glass Collector, May 2019). When I cleaned this “B” mold half-pint Warner’s, I noted that it had a weak mold impression, particularly in the details of the safe. I compared it to the half-pint Warner’s in my collection that I had purchased, and it also had a very weak impression of the safe. Looking at the bottom, I saw that it, too, was a “B” mold!

Online eBay and Google searches found other half-pint Warner’s “B” mold bottles, all with this identical poorly detailed safe. The “B” mold half-pint Warner’s with the weak embossing was definitely a thing!

As I was exploring these “B” molds, I noticed that there was also a half-pint blob of “Warner’s Cure” with an “A” embossed on the base, which had a much better mold impression than the “B,” including a very nicely detailed safe. I saw both these “A” molds online and held them in my hands at shows. I wanted one…badly. Yes, all these possibilities were going through my mind in the five seconds between realizing I was digging a half-pint Warner’s and having it out of the ground and turned around so that I could see what I had!

Upon flipping the bottle over and very carefully wiping away the ash, I was delighted to see that it was indeed a half-pint “Warner’s Safe Cure” (No 5WR in Michael Seeliger’s 2016 book, H. H. Warner His Company & His Bottles 2.0). And I was ecstatic to see that it had a gorgeous, highly detailed safe, and overall mold impression. [Photo 8] “Yes,” I loudly exclaimed to myself (and to the birds chirping and squirrels chattering nearby). My next thought was, “No way this is the B mold!” Quickly looking at the base, I was very gratified that my suspicions were correct—it was the “A” mold!

Seeliger’s notes on the 5WR tell us this smaller-sized bottle “was introduced in 1893 when the Warner Company returned from the London investors back to Rochester as Warner’s Safe Cure Co. Originally, the price was 65 cents, but later was changed to 50 cents. Although Warner used the small size for many products, he did not introduce the smaller size to the United States until very late.”

I saw Michael at the June 2024 Saratoga Antique Bottle Show in Ballston Spa, New York, and asked what he might know about the “A” and “B” molds for the 5WR. Michael responded that he had not conducted a study of Warner’s molds, as there were just too many. He did say that the 5WR in his collection did have an “A” on the base and that this bottle was made from the mid-1890s until about 1908 or so. That certainly fits the age of the bottles I’m digging in this dump. Digging this “A” mold Warner’s 5WR was a wonderful way to validate further my experience and research that these molds are indeed for real. See [Photo 9] for a side-by-side comparison of the “A” and “B” molds, with the “A” mold on the left, which shows more detail in the safe.

One More Seal

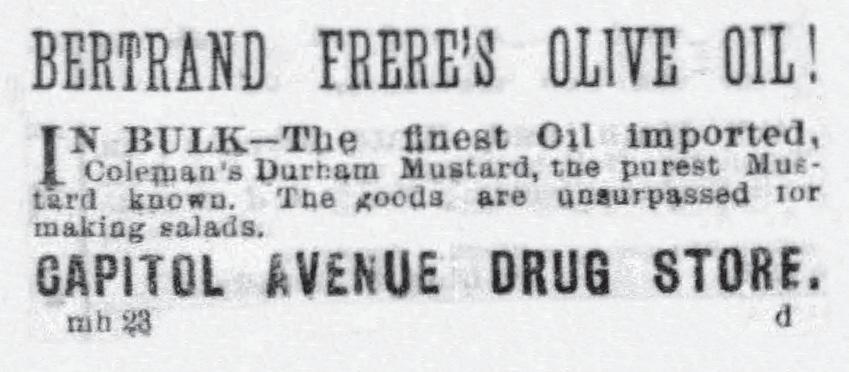

Soon after the thrill of finding the Warner’s, another noteworthy keeper was unearthed in this Memorial Day 2024 pit, and I’m happy to say that it was the second seal bottle I’d dug in a month! Tall and thin, standing at 9 3/4 inches and aqua in color, the seal on the shoulder reads, “HUILE D’ OLIVE SUPERFINE BERTRAND FRESE GRASSE.”

[Photo 10] This translates to “Olive Oil Refined, Bertrand Brothers, Grasse.” Grasse is a beautiful town on the French Riviera [

[Photo 10] Quart-size “Bertrand” olive oil, dug Memorial Day 2024, next to pint-size example dug in 2023.

[Photo 11]

Capitol Avenue Drug Store advertisement for “Bertrand Frere’s Olive Oil.” Hartford Courant, 1878 nestled in the hills between the Alps and the Mediterranean, just north of Cannes (of film festival fame). Grasse is better known for its perfume, which the Bertrand Brothers also produced. According to Baybottles.com, two brothers, Baptistin and Emelien Bertrand, founded this perfume and olive oil business in 1858. The business operated in Grasse under the Bertrand Freres name for well over 100 years. In 1878, the Capitol Avenue Drug Store advertised “Bertrand Frere’s Olive Oil.” [Photo 11] Later, in 1898 and 1899, Fraser, Viger & Co., a self-described “grocer and wine merchant” located in French-speaking Montreal, Canada, advertised their olive oil using the French wording embossed on the subject bottle “HUILE d OLIVE.” I’ve always had a fondness for these French olive oil bottles with the big, applied seal, so it was wonderful actually to dig one!

Thick as a Brick

Around 2:15 pm, as I was chipping into the last remnants of undug ash this hole had to offer, I came across a large (9 ¼” x 4 ½” x 2 ½”) reddish-brown brick. We do find bricks in these dumps, and typically, they’re of no interest and are tossed back into the hole. This one, however, to my surprise, was very heavily and attractively debossed “SUPERIOR FIRE LININGS CO No 1 TRENTON NJ.” [Photo 12] I’d love to hear from any readers who collect bricks and can tell us something about its history and interest to collectors.

Jars Are Cool, After All

For reasons that are hard for me to relate to now, I confess to being a fruit jar snob in the first 50 years or so of my digging and collecting antique bottles. Perhaps it was the fact that I considered myself a bottle collector, and these jars are not bottles per se. Or it could be that I saw them as something that grandmothers collect, so they’re not cool. Whatever the reasons, my first instinct was always to sell any jar I dug, and I sold dozens over the years.

It was two somewhat unusual jars that I dug up over the past few years that initiated a transformation in my appreciation of these highly collectible, hand-tooled American artifacts. The first of these was a pint-sized aqua jar embossed on the front in an oval slug plate “PRESERVING HOUSE MAXAMS NEW YORK.” and base embossed “GLASS MFG CO COHANSEY PHILADA.” Dug in June 2016, See Collecting a Potpourri of Dug Bottles in the April 2019 issue of Antique Bottle & Glass Collector. The jar was dug with a fully intact lid held on with the remnants of a wiring apparatus unfamiliar to me. It was so rusted that it crumbled apart as I attempted to screw the lid off the jar. I was struck, though, by the unusual embossing (at least for this digger), as well as the distinct straight-sidedness of the jar compared to a typical Mason jar. I was also stoked to see the glass house embossed on the base, which enhances the appeal of a bottle (or jar) for most collectors.

When I showed pictures of the jar to my digging buddy Gary Mercer, he exclaimed, “That’s a Cohansey!” Ah, so the base-embossing actually identifies the odd wire clamping system! At his urging, I immediately ordered the latest copy of Douglas M. Leybourne’s Red Book No. 11, The Collector’s Guide to Old Fruit Jars. Upon receiving the book shortly thereafter, I found the jar listed as #2138, with a value of $500 and up! The jar pictured in the book (a line drawing) was, however, a little squatter than mine.

While value does not determine whether I keep a bottle, it certainly got my attention, and the decision to keep the Maxam’s was a no-brainer. Additionally, as luck would have it, my neighbor, who collects antiques, had a slick Cohansey jar with an intact wire closure that I transferred to my jar, and it fit perfectly.

Dug in the summer of 2022, “The Mason Jar of 1872,” was a second remarkable jar that captured my attention as something very appealing and out of the ordinary. I’d dug and seen many Mason jars in my 54 years of digging, but this one was unknown to me, which made it an exciting discovery. I also found it compelling to see a date other than the ubiquitous “1858” on a Mason jar! Listed as Jar #1750 in Red Book, it’s described as having a ground top and is valued at $60 to $90.

I had the jar professionally cleaned by Leo Goudreau, and David Rittenhouse provided an original glass lid. David did not have the matching zinc band, however, and suggested I reach out to Rich Green for that. Rich responded that the actual zinc bands for these jars were very rare, but he said that he could fabricate

[Photo 13] “Maxams one by cutting and soldering together actual relic Mason jar bands. I said go for it. With the assistance of these three antique jar-collecting friends, a completely beautiful jar was literally resurrected from the trash heap. See [Photo 13], paired with the Maxams.

Preserving House New York” and “The Mason Jar of 1872.” The two beautiful dug pieces that converted me to a passionate jar collector.

With my passion for antique fruit jars now fully awakened, I discovered several worthy additions to the collection in 2024. While none of them are particularly valuable, they all passed my qualifiers of being old, interesting, cool, and in nice condition. Following is a sampling of some of the good ones:

Friday, May 24, 2024: Red Book #1736: Midget pint in aqua. Ground lip. “MASON’S” Keystone logo “IMPROVED.” Red Book values at $50 to $75. Professionally cleaned by Leo Goudreau, with a glass lid and zinc cap provided by Rich Green.

Saturday, June 15, 2024 (dug two jars): Red Book #628: Quart jar in aqua. Ground lip, glass lid, and circular wire clamp. “COHANSEY” in arched lettering across the top third. The Red Book values range from $35 to $50. Cleaned by Leo Goudreau. The glass lid and zinc cap were provided gratis by David Krzemien.

Red Book #1069. Quart jar in aqua with nice whittling. “THE GEM.” On base “PAT’d DEC 17 61 REIS SEPT 68 & JAN 19 ‘69 PAT’d NOV 26 1867.” Red Book values between $10 to $12. Cleaned by Leo Goudreau. Rich Green provided the glass lid and zinc cap.

Sunday, July 14, 2024 (dug two jars): Red Book #1722. Quart, aqua, ground lip “TRADE MARKS,” “MASON’S,” “CFJ Co,” “IMPROVED.” (Note: Not an error above; it is embossed in the plural “TRADE MARKS.” Red Book value $10 to $12. Rich Green provided a glass lid and zinc cap.

Red Book either #1920 or #1925-1. Half gallon, aqua, ground lip. “MASON’S,” “CFJ Co,” “PATENT NOV 30th 1858.” Red Book value $10 to $12. This jar was found in the very bottom of an eight-foot-deep hole under a tree and came out very clean. David Krzemien provided a lid and zinc cap at no cost.

Friday, August 16, 2024: Red Book #1939: Light green pint straight-side ground lip “MASON’S,” German iron cross emblem “PATENT,” “NOV 30th 1858.” On base, “PAT NOV 26

“Trade Marks Mason’s CFJ Co Improved” RB#1722, half gallon “Mason’s CFJ Co Patent Nov 30th 1858” RB #1920, Pint “Mason’s (German Cross) Patent Nov 30th 1858” RB #1939.

[Photo 16]

Beautiful reproduction zinc tops. On left, “Boyd’s Genuine Porcelain Lined” with a German iron cross in the middle, for the “Mason’s” pint, Red Book #1939, provided by Rich Green. On right, “Consolidated Fruit Jar Company New York” with “CFJ” monogram in middle, for the half-gallon “Mason’s CFJ.” RB #1920, provided by David Krzemien.

67,” “143.” This jar has an unusual look due to its straight-sided design. Red Book value is only $4 to $6 in aqua. Rich Green provided a milk-glass lid and a beautiful repro zinc lid embossed “BOYD’S GENUINE PORCELAIN LINED” with a German cross in the middle. [Photos 14, 15 and 16]

Maple Syrup in a Ball Jar

If there are bottle gods or jar gods, they decreed that the old idiom, save the best for last, would apply to the jars I dug in 2024. It was Saturday, September 14, a pleasant sunny day in the low 80s. It was day two at my designated spot, and I had bottomed out at just 7 ½ feet (this section, close to the landowner’s garage, is shallower than the center of the dump). I was also just a few weeks away from retirement after 40 years with New York State, so the excitement from that provided a pleasant baseline for a good vibe for this dig.

Additional positive resonance for this day came from several good bottles found as I chipped away at the sides of the hole, working my way from the bottom up, two of which I’ll briefly highlight:

1) Quart aqua hutch embossed in slug plate “WEINSTEIN & KAPLAN REGISTERED ALBANY N.Y.” The first of these I’d ever dug, an uncommon and attractive bottle to add to my quart Hutchinson collection.

2) “COCHRAN BELFAST” round-bottom torpedo with a small base that allows the bottle to stand (but rather precari-

[Photo 17]

Two bottles dug September 17, 2024 glistening after cleaning. On left, quart aqua Hutch embossed “WEINSTEIN & KAPLAN REGISTERED ously). I’d found one of these the day before and three on this day. These bottles are very heavy and must be made from a relatively hard glass, as they seem to be impervious to staining. See [Photo 17], which shows these bottles side by side after I cleaned them the next day.

ALBANY N.Y.” On right, round bottom “COCHRAN BELFAST” with a tiny base that allows the bottle to stand.

It was in this “Good Day Sunshine,” optimistic, cheerful mindset while chipping into the early 1900s layer of virgin ash at about four feet deep that a quart-sized jar was suddenly revealed. Its intense, deep aqua-blue color immediately energized me. Still, as a recently converted devotee of jars, I chipped away at it with all due caution, taking care to avoid the packed coal ash that surrounded it. Once freed from its grave, I wiped away the ash in short order and was encouraged to see that this was indeed an odd one, embossed as follows, “PACKED IN ST JOHNSBURY VT, BALL (in script), SURE SEAL.” On the reverse shoulder, “BY THE TOWLE MAPLE PRODUCTS CO.” Embossed on the base, “PAT’D JULY 14, 08.” Wow, a Ball Maple Syrup jar! [Photo 18] This was indeed unusual, and I knew I had something good. Based on the patent date and the fact that it was

[Photo 18] the lid. Damn!) The book tells us the glass crown is the standard “Unmarked Ball Blue Lightning-style Lid.” However, the book does not mention that, although these lids are standard and nofrills, they are very scarce and hard to find. Does anyone have an unmarked Ball Blue Lightning-style lid for sale and perhaps the expertise to reconstruct the wire bail system for this jar?

Freshly dug Red Book #320-6 juxtaposed with it sparkling after cleaning the next day.

A “Ball” jar used for product packaging by “The Towle Maple Products Co,” based in St. Johnsbury, Vermont.

Below is interesting information about the Towle Company and its jar, pulled from an August 20, 2022, online article by Matthew Thomas titled Maple Syrup History; Exploring the Past World of Maple Syrup; The Towle Maple Products Company St. Johnsbury Ball Jar. “Among Ball jar collectors, the Towle’s St. Johnsbury Sure Seal jars are a widely sought-after series. These round jars and glass lids with a snap-down, Lightning-style wire closure were manufactured in a unique 22-ounce size in the Ball Sure Seal shape exclusively for the Towle Maple Products Company and were not available or sold to home canners. Often referred to in the Ball jar collector community as packer jars, product jars, or customer jars, these jars were initially filled with various brands of the Towle Company’s blended syrups for retail sale in shops and grocery stores, most notably the signature Log Cabin Syrup brand.

“There are at least nine variations of the jars that can be divided into groups based on glass color, closure style, and embossing text. For example, most of the jars are “Ball blue” in color and exhibit the tell-tale circular scar from being made on the Owens Automatic Bottle Machine.

[Photo 19] a Ball jar, I assumed it would be ABM, and indeed it was (as verified by the Owen’s circle on the base). And although the rusted remnants of the wire bail system were still there, the coveted glass lid was missing. Despite my best efforts to scour the surrounding area and sift through the ashes with my fingers, I could not find it. Sigh.

Beautifully labeled “Towle’s Log Cabin Syrup.” Example of a Towle’s St. Johnsbury Ball jar with intact Log Cabin Syrup paper label. From the collection of Scott Benjamine.

Looking up the jar later that evening, it appears to be “Ball Sure Seal” 320-6 in Red Book described as 22 oz., 7-1/4 inches tall, and valued at $100 to $150 (the value is 50 to 60% less without

“Although the jars found in most collections today do not have paper labels, initially, all the Towle’s St. Johnsbury jars had paper labels on their front face, either the well-known Log Cabin Syrup brand label or one of a few other brands used by the Towle Company. [Photo 19] Towle’s St. Johnsbury jars with intact paper labels from known collections include Log Cabin Syrup, Great Mountain Brand Syrup, and the Crown of Canada Brand Syrup. The Towle’s St. Johnsbury jars can be tightly dated to between the middle of 1910 and the end of 1914, based on the known dates of operation of the Towle Company plant in St. Johnsbury, Vermont, which is discussed below.

“All the jars in the Ball blue glass color variation feature the Ball name embossed on the back face in script with an underline, a looping double LL, and a dropped “a,” which are known to date between 1910 and 1923 on Ball-made jars. This detail corresponds to the historical record that the Towle Company operated in St. Johnsbury from 1910 to 1914. Under the scripted “Ball” name in capitalized sans serif typeface are the words “SURE SEAL.”

“The Towle’s St. Johnsbury jar is so notable and popular among Ball jar collectors that it has been recognized and described in Red Book 12 The Collectors Guide to Old Fruit Jars. The most recent edition of the Red Book, published in 2018, lists nine variations of this jar (RB 320-4 through RB 320-12).

“Also unique to these jars is a very specific and hard-to-find glass lid. According to experts in the Ball jar collecting community, the correct glass lid for these jars is in the same Ball blue color as the jar, but unlike other similarly shaped and sized lids, the proper lid has a shallower depression in the center and a less steep central ramp.”

Whoa, a Rare Local Green Pharmacy

My permission spot has been very generous in terms of local drug store bottles, particularly from cities such as Albany, Schenectady, and Troy, New York, as well as from New York City and even out-of-state places like Portland, Maine. While these local drug store bottles are often wonderfully embossed and representative of local history, the vast majority of them were made in colorless, clear glass.

Friday, August 16, 2024, was a hot and humid day with a high around 87. I was near the landowner’s 1920s-era detached garage and starting a new pit. I first spent time transplanting small trees, ferns, and shrubs from the area I was about to dig to areas that had been recently dug to keep the landowner’s property as green and attractive as possible. I’ve been pleasantly surprised at how well these transplants have taken to their new homes, and I’ve done the same in other dumps I dig. The process requires filling in my holes, which, by ensuring the undug areas aren’t covered by backfill, makes digging the next hole much easier and helps to ensure that very little dump is left undug.

I opened up a large pit to maximize my chances of success and stumbled upon a section of undug dump I’d somehow missed between holes. Being of the mindset that no bottle is left behind, I’d need to dig this section out, adding to my workload. At about 1:15 pm, I was excavating this little missed section when I noticed, out of the corner of my eye, just a few feet away and to my right, a bottle I had just tossed out of the hole without seeing, feeling, or hearing it. I quickly picked it up and was stunned to see that it was an embossed, emerald-green pharmacy bottle! [Photo 20] Looking at the bottom row of embossing, I saw “SCHENECTADY” and recognized the bottle by its distinctive form, recalling that it was rare. The bottle is 5 ¼ inches in height and embossed “3iv H.A. KERSTE PH C PRESCRIPTION DRUGGIST SCHENECTADY, N.Y.”

Stoked out of my mind, I leaned back to thoroughly examine the bottle to confirm it was in good condition. Five seconds into the inspection, I was devastated to see a large crack running around the edge of the back of the bottle. Despite my disappointment that it was not perfect, it was in one piece, and I knew I had a great and rare local bottle. To my surprise, the rest of the hole turned out to be rather bland and lifeless industrial ash with very little of interest emerging. Additionally, I failed to take the heat and humidity into consideration and did not bring enough water, running out by 2:30. I paid the price with muscle cramps...ugh.

Cleaning the Kerste bottle that evening, I was thrilled with how beautiful it was (despite the crack) and how it sparkled on the backlit glass shelves in my Bottle Room. I next looked in the reference guide, Old Schenectady Bottles, by Roy Topka, to see what information he had on Kerste. It’s the first drugstore bottle listed in Roy’s book, but it only mentions that the colorless bottle is common but rare in green and cobalt blue. I next contacted Roy by text, along with Schenectady bottle collectors Jeff Ullman and Todd Cagle, who specialize in colored pharmacy bottles. They were all very happy for me, congratulating me on my find. As I expected, they confirmed they each had one of these bottles in their collections (I knew I’d seen them before somewhere!) They also added that to the best of their knowledge, these three were the only other green Kerste bottles they knew of, so mine was the fourth. Not only that, their three Kerste bottles are three inches in height, while mine is 5 ¼ inches, making mine, as far as we know, unique. That was very exciting to know!

I was able to learn a bit more about H. A. Kerste and his Schenectady pharmacy business from an August 29, 2013, Times Union article, Prescription for Nostalgia, by Cameron J. Castan. The story references the drugstore Kerste operated at 402 Union Street and the city’s decision to recognize the building as a historic landmark.

“Locals stopped in for remedies for ailments ranging from stomachaches to burns. The store also catered to children, with shelves of toys and candy. The three-story building was constructed in 1892 by Henry A. Kerste, a pharmacist and prominent member of the community. It now houses an accounting office on the second floor. The sign for a defunct Afghan restaurant, Kabul Night, remains on the first floor.

“At 11 am Saturday, September 7, city officials will gather outside the building to recognize Kerste’s Drug Store as a historic landmark. Kerste, who received his degree from Albany College of Pharmacy in 1886, was also known as one of the first people in Schenectady to ride a bicycle as well as to own a car. So many people pass by this building every day without giving it a second thought. If you look closely, you can still make out the tiles at the entrance that say Kerste’s, said Andrew Conti, whose grandfather bought the pharmacy in 1940. Ercole Conti was trained by Kerste himself and operated the store until it closed in 1976, succumbing to competition from supermarkets and large discount chains.

“The second floor of the mom-and-pop pharmacy served as the Contis’ home for almost half a century. “I wanted a way to preserve all the special memories I had there. The drugstore is truly part of the fabric of Schenectady’s history,” said Conti, who pushed for the building’s landmark status.

“Kerste’s was renowned in the late 1800s for “The Arctic,” its large, hand-carved oak and marble-topped ice cream soda fountain. The structure was later sold to a museum in Vermont. I think Schenectady is going through a period of revival. I’m glad that buildings like my grandfather’s are being rediscovered, Conti said. It’s not unreasonable to think that Schenectady was truly a birthplace of innovation.”

Further internet research tells us that in the 1900 census, Henry A. Kerste was listed as a druggist, born in New York City in 1865. His wife was Sussie Kerste, age 32.

According to Roy Topka, Ercole Conti, the person who bought Kerste Pharmacy in 1940, told him in the 1970s that there was also a cobalt blue version of the same bottle available in three sizes. However, no one we know has one in their collection!

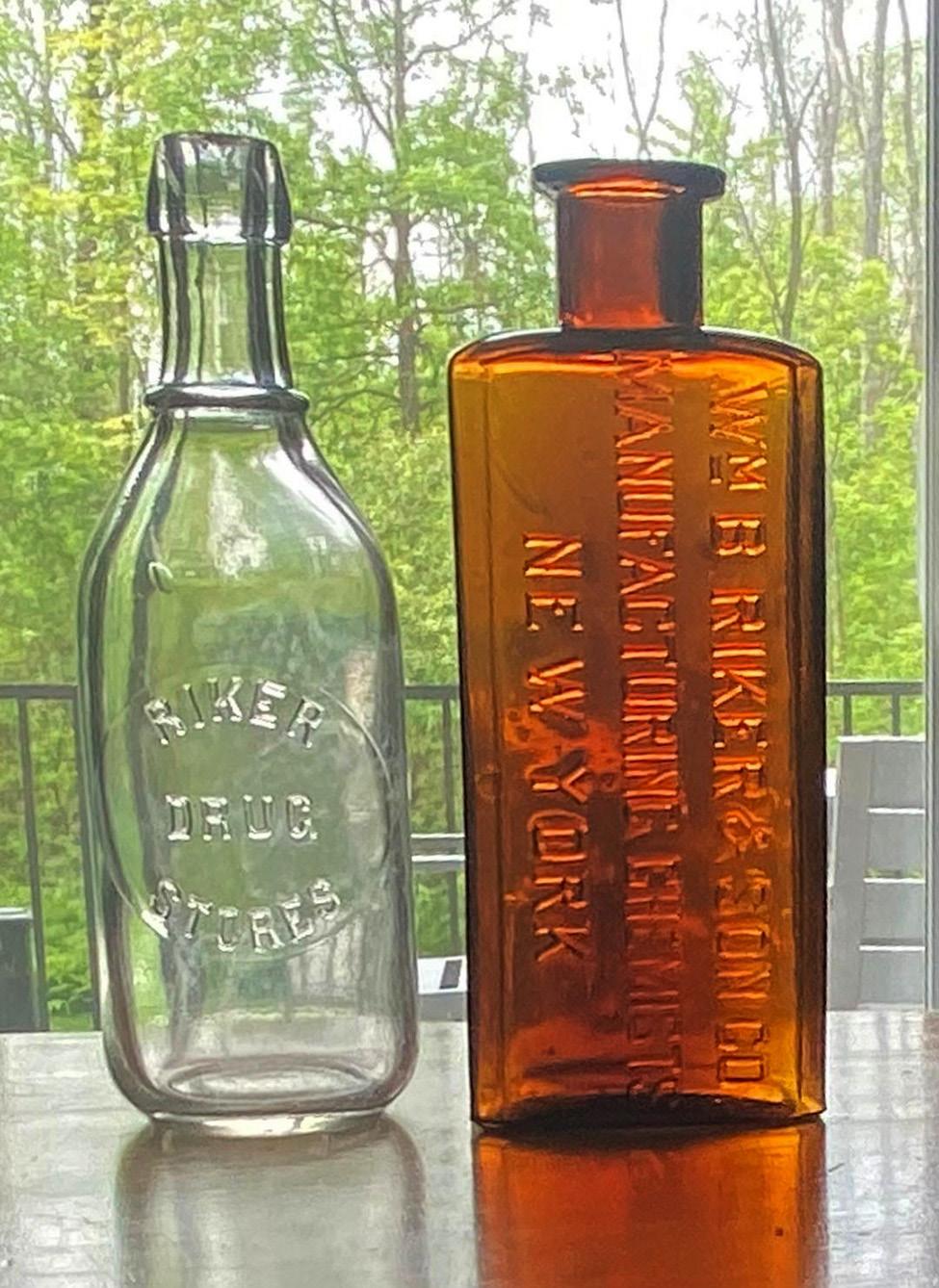

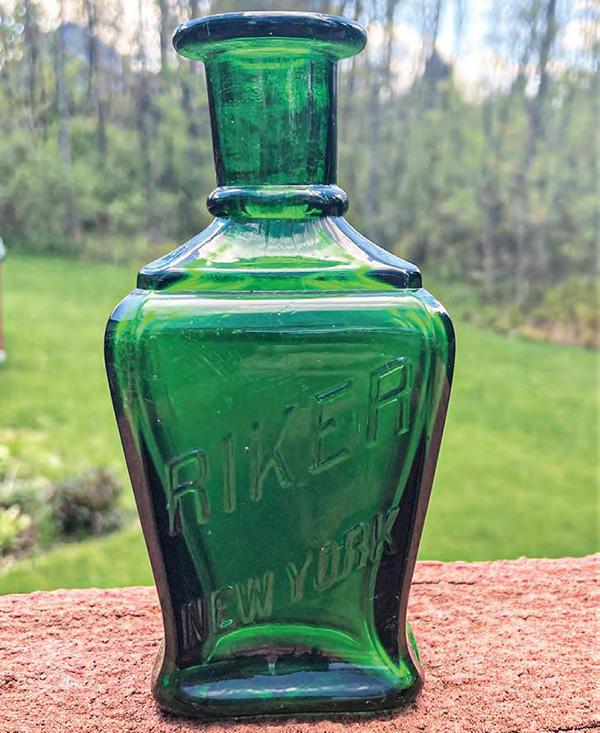

Riker Bottles

Riker was a major drugstore chain founded in the mid-late 1840s that lasted into the 1920s. They made several collectible embossed bottles. I’ve been fortunate enough to dig a few of them over the years. The first of these was an emerald-green, pinchedwaist hair bottle, four inches high, dug on September 12, 2020 [Photo 21] and featured in my article, The COVID Bottles of 2020, published in the October 2021 issue of Antique Bottle & Glass Collector. Labeled versions of this bottle read “Septone Soap, A Shampoo.” Riker was selling a hair preparation called “Riker’s Septone” as early as 1878 and as late as 1907.

side of the piles of branches they’ve thrown over the fence for decades. There was a huge tree stump in the way, but fortunately, the stump was rotted and soft. The first foot or so of this dump was an organic humus layer from the leaves and detritus that had accumulated since 1912 or so when this dump was no longer in use (and houses were built over a big section of it). I typically don’t find much in this layer, so it was a nice surprise when I tossed a shovelful of dirt from my newly started hole and saw a nice, cylindrical bottle roll out. I instantly recognized it as a “Citrate of Magnesia.” I’d been finding quite a few of them in the last few years and have been collecting them. Hoping that it would be embossed, I was pleased to see it was indeed marked “RIKER’S DRUG STORE” in an oval slug plate. Wow, cool, I thought, another Riker’s bottle I don’t have. I planned to soak this colorless bottle under the sun to see if it would become a nice shade of lavender in a year or two. Magnesium citrate is a legitimate saline laxative that treats constipation. Based on the number and variety of these bottles that I (and other diggers) have found, this medicine seems to have been quite popular around the turn of the century. I see that it is advertised for this same use today, which would seem to verify it actually works.

My permission dump yielded two Riker bottles in 2024, the first on Friday, July 12, 2024. It was a brutally hot and super humid summer’s day. I was digging very close to the property owner’s detached garage, with his car parked on the other

A month later, late in the day on Sunday, August 25, as I was close to finishing up a hole, I was chipping away at the sides just a few feet from the top. While caving in this top layer, a big brick-shaped amber bottle was revealed. Ooh, very cool, I thought, as these are sometimes nicely embossed medicine bottles! Because the ash was soft, the bottle was quickly in my hands. Turning the bottle over, I could see, to my great satisfaction, that it was indeed heavily embossed “WM B. RIKER & SON CO., MANUFACTURING CHEMISTS NEW YORK.” Way cool. A big (eight in. tall), beefy, amber pharmacy bottle from Riker, a company that I was beginning to have an affinity for! The bottle was in sparkling condition, so there was no need for a professional cleaning with this one. I also liked the peculiar stubby neck. [Photo 22]

Google AI provided this succinct history of the Riker Drug Stores:

“William B. Riker, a native New Yorker, was born in 1821 and died in February of 1906. During the early to mid-1840s,

Riker served as a clerk for a druggist named Meakin, whose business was listed at 511 Broadway. Riker later worked with a druggist named Dr. Hunter. Sometime after 1846, Riker established his first drug store in Manhattan’s Flatiron District at 353 Sixth Avenue.

“His son, William H. Riker, later took over his father’s chain of stores and personally operated them through the early 1890s. The firm of William B. Riker & Son was still selling products into the early 20th century. In 1907, Riker acquired the Charles P. Jaynes & Company drugstores, based in Boston, Massachusetts, and merged them with Riker, forming Riker-Jaynes. Then, in 1910, Riker-Jaynes merged with a competing drugstore chain, Hegeman & Co., becoming the Riker-Hegeman Company and creating a chain of over 100 stores. In 1916, the Riker-Hegeman stores were acquired by the newly formed Liggett Company (which in turn was owned by the United Drug Company). In the early 1920’s Liggett’s advertisements still mentioned that some of their locations were “former Riker-Hegeman stores,” but by the mid-1920s, the Riker-Hegeman name completely disappeared from their drugstore ads.”

The Riker bottles I’m digging in this dump are likely from 1895 to 1910.

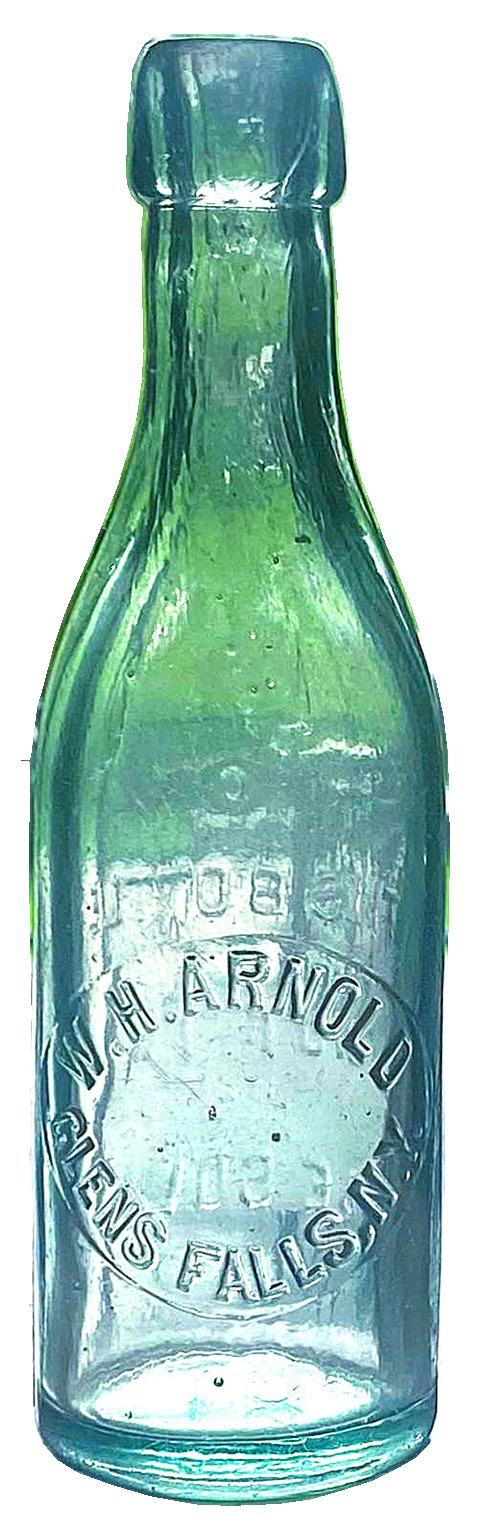

Is it a squat soda or a split beer?

On Friday, July 12, a nice surprise came at the very end of a long day of digging. My chipping tool revealed an aqua blob top, and pulling on it easily released it from the soft coal ash. I was astonished and very pleased that it was a squat soda, embossed in the slug plate “W.H. ARNOLD GLENS FALLS, N.Y.,” and on the back, “THIS BOTTLE NOT TO BE SOLD.” I’d never seen the bottle nor recalled hearing of this bottler. I was unable to find any information about Arnold online, so I reached out to the human encyclopedia, Manny Birittieri.

According to Manny, Arnold moved to Glens Falls in 1889 and was in the liquor business. Sometime around 1894, he extended his business by adding the bottling of soda water and other drinks. Manny mentioned that Arnold was also a brewer. To add to the mix, I found Arnold Hutchinson bottles for sale online. With Arnold going into business around 1890 and with examples of Hutch bottles he was using for his sodas out there, it seems more likely this is a split beer. Or perhaps Arnold wasn’t sold on Hutch bottles at first and used a squat soda bottle for his early pop bottles?

[Photo 23]

[

In Closing

The bottles I dug in 2024 and kept for my collection will exemplify my “digging what I dig” bottle-collecting philosophy. I would never, for example, attend a bottle show or look at an auction for a “Triloids Poison,” a “Propper & Schulhof, New York” strap-sided whiskey flask, or a “Towle Maple Products Co.” Ball jar. But the unpredictable randomness of fate gifted them to me, and I am now the proud and very pleased caretaker of these marvelous artifacts. When I gaze upon these treasures in my Bottle Room, they reignite the happy memories I have of the exhilarating moment of discovery when I unearthed each one of them. I’m very appreciative of the fact that I still have promising unexplored spots to excavate and that, at the age of 64, I’m still healthy enough to dig. May the good times continue.

References—Source—Bibliography:

Wikipedia: Mercury Chloride (Triloids main ingredient): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mercury(II)_chloride

Roseville Pottery History, Marks, and Artists (Makers of DOG stoneware bowls): https://justartpottery. com/pages/about-roseville-pottery

Paul Jones; History of Four Roses: https://sippinghistory.com/2021/11/09/four-roses/

Sealed Bottles on Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sealed bottles

David Jackson and his Applied Seal Bottles: https://www.peachridgeglass.com/2012/12/david-jacksonand-his-applied-seal-bottles/

Boston University on Alcohol consumption prior to prohibition: https://www.bu.edu/articles/2020/pov-the-100th-anniversary-of-prohibition-reminds-us-that-bans-rarely work/#:~:text=From%201900%20until%201915%E2%80%94five,able%20to%20afford%20illegal%20 liquor.

Old Schenectady Bottles, by Roy Topka

Michael William Seeliger’s 2016 book, H. H. Warner His Company & His Bottles 2.0. Bertrand Brothers Olive Oil: https://baybottles.com/2022/05/08/huile-d-olive-superfine-bertrandfreres-grasse/

Towle Maple Syrup Ball Jar: https://maplesyruphistory.com/2022/08/20/the-towle-maple-productscompany-st-johnsbury-ball-jar/

H.A. Kerste PH C Prescription Druggist Schenectady N.Y.: https://www.timesunion.com/business/article/Prescription-for-nostalgia-4772415.php

August 29, 2013 Times Union article, Prescription for Nostalgia, by Cameron J. Castan: https://www. timesunion.com/business/article/Prescription-for-nostalgia-4772415.php

Google AI: a division of Google dedicated to artificial intelligence

Editor: Read these other recent articles by John Savastio in the FOHBC.org Member Portal.

KU-8

$9,000