13 minute read

Flying with the drones

As pilots that pushed back against recent Airspace Change Proposals for drone Temporary Danger areas in Scotland, Hamish Mitchell and fellow Prestwick Centre ATCO Derek Pake went in search of the drone operators to see if some co-operation might be in order…

Let me state quite clearly from the start, I am not against the operations of Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS, or drones as they seem to be commonly referred to), and like most of us, I can see there is the potential for great benefits, if integrated properly and respectfully with existing airspace users. What I am against is a process that short-circuited the normal consultation, that failed to properly engage or consider GA, and had minimal critical oversight from the CAA.

Advertisement

In my view these weaknesses in the ACP process have created a climate of suspicion and deep mistrust within the GA community, of both the drone operators and efficacy of CAA oversight. This serves no one well and all parties, including the CAA, should redouble efforts to build a more co-operative and trusting environment.

Close encounters of the ADS-B kind…

Throughout 2020, with Covid-dominating the headlines, few flyers realised the magnitude of drone research and Airspace Change Proposals (ACPs) about to be unleashed across the UK.

Given that GA was grounded for most of 2020, the flying community was very much ‘out-of-theloop’ regarding currency and procedures.

That changed on 11 January 2021 when, a random email from an LAA member, highlighted proposed Temporary Danger Areas (TDA) which would close vast areas of Class G airspace around Mull and Oban in Spring 2021, severely impacting all GA flying on the Scottish west coast. Further research and publicity followed, greatly supported by FLYER and other GA representatives, when it became apparent (much to everyone’s surprise) that there had already been previous trials and TDAs around Oban during the first 2020 lockdown, with more, particularly Lochgilphead (ACP-2020-055) awaiting approval in the CAAs ACP Portal.

Skyports mobile WhiteVan control centre

Inside WhiteVan, the Drone Operator position with multiple tracking and control consoles

While the absence of GA activity due to Covid presented a clear opportunity to trial TDAs and provide useful research, particularly in support of the NHS, it also created an unrealistic environment where drone operators were not exposed to the normal usage and users of these airspaces. This was compounded by truncated ‘consultation’ periods and hastiness to approve, as evidenced by differential response levels to ACPs before and after January 2021.

Reaction to the Mull ACP-2020-099 was forthright – more than 90 responses, in contrast to the dozen or so in 2020, resulting in a pause on that ACP. Attempts to include extra stakeholders in the delayed Lochgilphead trial (ACP-2020-055) disappointingly fell on deaf ears, particularly when the trial was further extended into April. This reinforced a widespread suspicion of hidden agendas and collusion. But, we are where we are. Mistakes in oversight have clearly been made, and an acknowledgement from the CAA to this effect would have been welcome.

Building bridges

In the spirit of co-operation, an offer was made to work with Skyports on informally testing ADS-B functionality and detection, which revealed that drone ADS-B Out units had a software fault, making them invisible to FR24 and SkyEcho2.

This was rectified in April and, as the Lochgilphead ACP was ending, my flying partner Derek Pake and I arranged a suitable day to conduct a comprehensive test, coupled with a visit to Skyports drone operations van, nicknamed WhiteVan located at Oban hospital. The WhiteVan setup had space for up to three Drone Operatives (DO), using the cloud-based Kongsberg Geospatial IRIS UxS tool for Situational Awareness (SA).

Hamish suspiciously investigates the SwoopAero Kookaburra Mk3 on the launchpad at Oban Hospital

This is an Unmanned Traffic Management (UTM) platform, which can be deployed anywhere in the world, giving live drone locations, battery life, ADS-B traffic, speed, height, diversion and checklist information. The drone operated from the hospital helipad, but could be tactically landed at smaller destinations using a QR code landing pad coupled with an onboard camera sensor. The majority of the 12-week Lochgilphead trial (ACP-2020-055) was funded by European Space Agency (ESA) and Skyports, with no cost to the NHS. Command and control was provided via the Vodafone 4G Mobile network, with satellite back-up (Iridium Constellation) in case of signal loss. GPS was via Galileo and GLONASS, with two redundant GPS receivers onboard.

RV-8 vs Kookaburra trial

The drone operators’s view of an encounter between drone KA333 and our RV-8 G-WEEV. The drone has commenced an avoidance orbit to the right

The drones used by Skyports were SwoopAero Kookaburra Mk3s, manufactured by 3D printing in Melbourne, Australia. Each drone is fitted with a uAvionix Ping1090i ADS-B transceiver (same manufacturer as the GA SkyEcho2). Four rotors are used for vertical flight (take-off, land and emergency) and two for forward flight, powered by independent battery systems. The Kookaburras weigh 17kg and have a maximum speed of 60kt. ADS-B reception is poor in the trial area so Skyports had installed several temporary ADS-B In sensors at either end of the TDA698 complex, although these did not feed into Flight Radar 24. Trial drones would fly northsouth routes at up to 360ft agl at 50kt within the TDA698 complex.

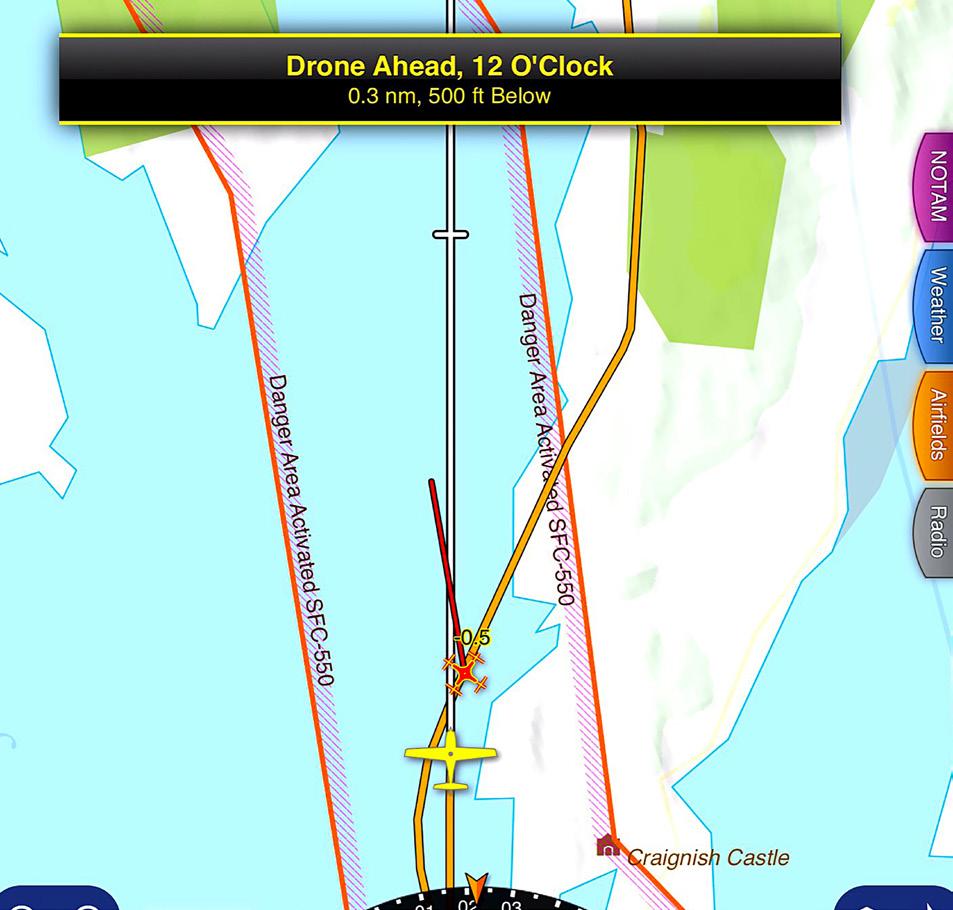

The RV-8’s view of the airspace shown on screen above – spot the drone at lower altitude and the RV-8 shadow…

The aircraft we used was G-WEEV, an RV-8, fitted with an ADS-B Out Trig TT21 Mode S transponder – with access to PowerFlarm, PilotAware, SkyEcho2, and an Android phone for back-up ‘WhatsApp’ communication with WhiteVan. This neatly (ironically) illustrates the confusing plethora of available protocols. We only needed ADS-B, so simplified the setup – SkyEcho2 coupled to SkyDemon on an iPad carried by the Weapons Systems Officer (‘Wizzo’) otherwise known as the onboard ATCO in the backseat.

Trial expectations

Skyports wanted to test how the drone and its ground-based SA platform performed under different approaches between the RV-8 and drone. Incidentally, we found out afterwards it was also being watched on IRIS from Melbourne (at 0200hrs) by bleary-eyed SwoopAero staff, and it would be interesting to get their feedback. We flew perpendicular, head-on, and overtake approaches (from a range of greater than 5km) to test whether:

The RV-8 pilot could detect the drone both visually and using ADS-B In feed.

The DO could initiate a correct deconfliction manoeuvre based on information from the ground control station and SA platform.

The drone’s Detect And Avoid (DAA) solution could act as a safety net and automatically deconflict with the RV-8 based on the drones ADS-B In, when the system predicts a breach of the well-clear (WC) safety zone surrounding the drone.

Trial results

When the first drone’s (Registration KA348) ADS-B failed, the RV-8 pilot received a screenshot of its location from the DO. At a range of 1,500m the RV-8 crew visually acquired the drone.

Both the drone and ground SA system detected the RV-8 up to 25nm away (best case line-of-sight), displaying the position in WhiteVan and alerted the DO when the RV-8 was 7nm away.

If the RV-8 was anticipated to breach the drone’s 3D safety bubble, the drone correctly initiated a deconfliction orbit (200m radius at 50kt), and the SA platform also detected and alerted the DO.

The drone’s telemetry feed accurately located the RV-8 giving time for the DO to issue a loiter command (right-hand orbit) if required.

The RV-8 located the second drone, KA333, through its ADS-B Out signal, receiving the signal for 360° around KA333 from various ranges, depending on terrain, starting at 5km.

On each occasion, the system alerted the DO with estimated time for the RV-8 to reach the drone’s safety bubble, giving him time to trigger a manual avoidance manoeuvre.

Pilot’s view

Weather on the day was excellent, a light northerly wind, clear blue sky, few clouds at 3,000ft overland, QNH 1018, a chilly +5C, with a smattering of snow on the peaks. We departed Prestwick, flew directly to the trial area and immediately commenced the first set of runs. Bearing in mind we were looking down on the drone against a calm dark blue sea, the weather on the day really helped – sunshine highlighted the white drone, with no whitecaps on the water, which would have made it very difficult to spot. Flat light on a cloudy day, or over snow, would have made it very difficult over land, especially if the drone was at the same level or above, against a grey sky. Without the ‘trigger’ of an ADS-B detector it would be near impossible to spot a conflict by visual means (as by definition a collision situation would be on a constant bearing – not moving across the windscreen).

Pre-flight briefing sheet displays the drone flight path and planned RV-8 encounter profiles

The SkyEcho2 /iPad combination worked well, detecting the drone when in line-of-sight, although, flying at 350ft agl, it was often shielded behind terrain to the south (at Crinan) and to the north (at Seil) – at these times we were loitering at 1,200ft attempting to regain visual contact. Too much tech can lead to heads-down attitudes in the cockpit, and you must avoid getting drawn into screen-gazing. A small, remote ‘alert display’ would help. Bluetooth (BT) warnings are advantageous, but most audio panels only pair with one source, suggesting a BT headset might be a better option.

It was challenging, with a high workload, particularly to maintain altitude above the TDA in tight turns and visual with the drone on what felt like Combat Air Patrol! G-WEEV naturally wants to fly fast, so slower 90kt profiles were trickier. Clear unambiguous communication between crew, and a good pre-brief with WhiteVan meant the WhatsApp back-up was rarely needed. After completion, we triggered the drones anti-collision, did a welldeserved victory roll – and returned to Oban for celebratory sandwiches.

SkyDemon depiction of a head-to-head pass with the drone 500ft below

A catch-up confliction with the drone flying at 55kt and the RV-8 flying at 140kt, but 500ft above

A 90 degree intercept pass with the RV-8 accelerating to 160kt and descending to cross the drone, 600ft below. The drone software has anticipated the conflict and instructed the drone to commence a right hand orbit, which is seen starting in this view

The backseater’s view

Derek chips in and takes up the story. “When liaising with Skyports, several factors put us in a good position to conduct the mission. Firstly, the aircraft, Van’s RV-8 G-WEEV (fondly known as WeeVans), is very manoeuvrable, with a wide speed range from 90kt to 160kt. This allowed us to conduct various ‘intruder’ profiles against the drone in quick succession, as we could reposition quickly in relation to the drone’s track.

“Secondly, being a two-seat aircraft with large bubble canopy provided excellent visibility during close visual manoeuvres, for both pilot and Wizzo. A second ‘pilot’/observer was a positive safety measure to monitor aircraft height, speed, and position relative to TDA698 airspace, and assisted in establishing and maintaining visual contact with drone traffic.

“Using the SkyDemon EC display, the observer was able to locate the drones ADS-B Out and pass the location and vectoring solutions to the pilot, aiding visual acquisition and setup of the flight profile required for each trial.

“Prior to the flights, Skyports shared with us its desired location as well as the profiles it would like performed. We also discussed important safety information, such as WeeVans remaining above the TDA to ensure vertical separation at all times, and communication modes with the drone operations team.

“Once en route and approaching the trial area, we were notified that drone KA348 was airborne from Oban towards Lochgilphead. Unfortunately, there was no ADS-B received from KA348 so we asked the operator to send us the location. Skyports uplinked their ADS-B picture via WhatsApp and this showed us it was flying down the western shore of a small Loch we could identify from the air. Turning onto a likely intercept track based on this information, we eventually obtained a visual sighting at about 1,500m distance, not easy when you consider it has a small 2.4m wingspan and flying at very low level among the varying colour contrasts of the Scottish landscape. We were able to keep it in sight for the majority of its journey southbound and carried out successful conflict profiles against it.

“Shortly afterwards the operator advised that they would also be launching drone KA333 on the same route and we repositioned overhead Oban Hospital, soon picking up its ADS-B Out on the helicopter landing pad. Once airborne, we followed it southbound, ‘WEEVing’ around and carrying out overtaking passes, head on passes, and 90° beam passes, at a variety of closing speeds and vertical separation distances.

“On several occasions we were able to trigger the drone’s collision avoidance algorithm and watch it orbit right, attempting to increase the predicted separation against us. Quite a high intensity of concentration in both the front and back seats of the aircraft, but also good fun and satisfying to get right against a very hard to see target.

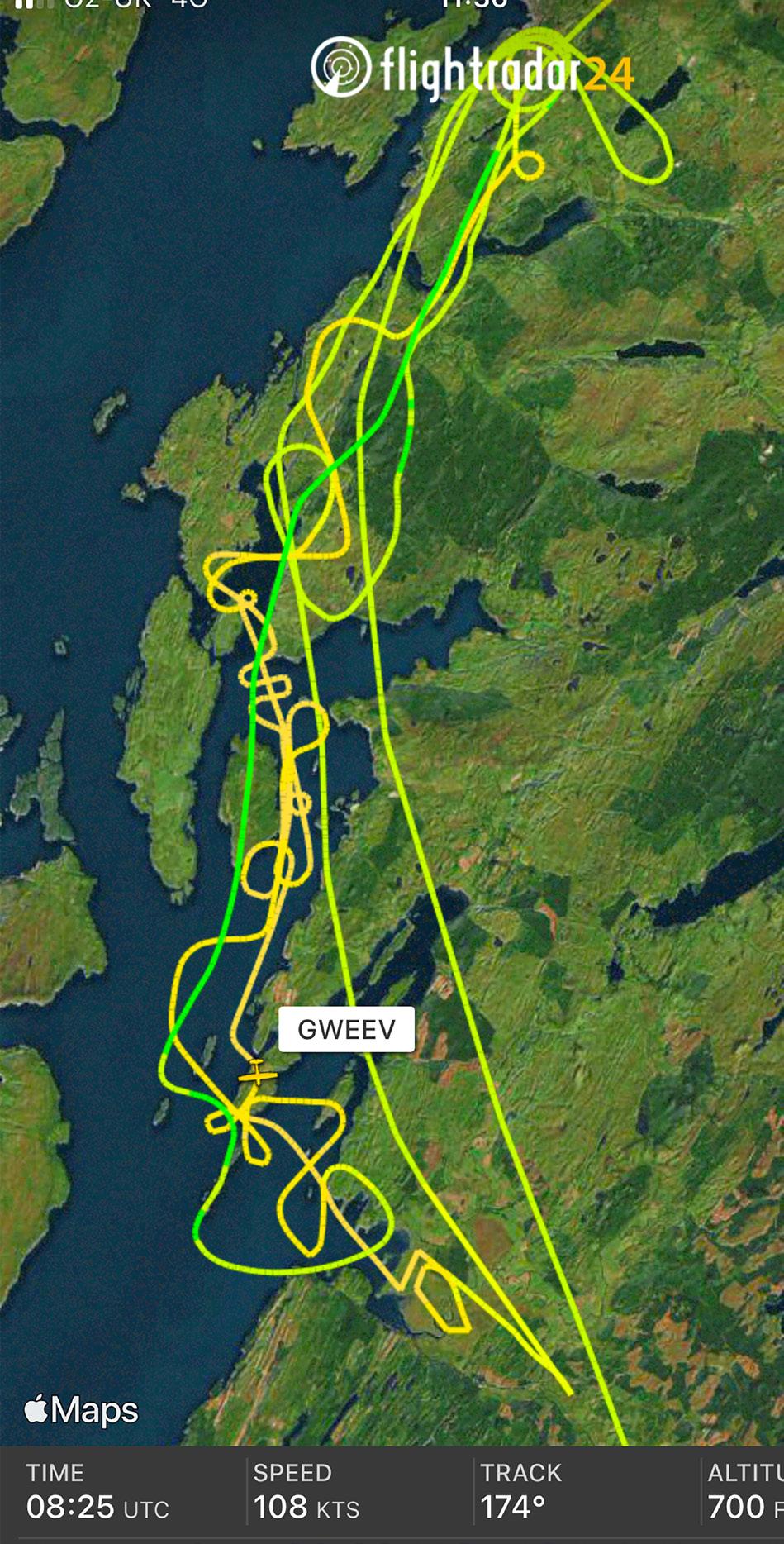

The first mission profile flown against drones KA348 and KA333. ‘WEEV’ by name, weave by nature!

“After a short comfort break at Oban Airport, we launched again to catch KA333 on its return journey and again conducted successful profiles before returning to Oban to meet the drone operations team and discuss the flight.” Looking ahead

It is accepted by the CAA, GA and the drone operators that TDAs are a very blunt instrument and not a viable long-term solution. They create a confusing patchwork of inflexible restrictions that do not satisfy the guiding principle of ‘integration not segregation’. Equally, temporary TMZs as a possible alternative to TDAs, while less restrictive, would still exclude non-EC equipped flyers.

Research into drone Detect and Avoid systems (DAA) continues apace, with acoustic, radar-based and visual solutions all in the mix for evaluation.

Hamish, Derek and G-WEEV, in normal ops

As the ‘disruptor technology’ that seeks to benefit financially, the onus should now be on drone companies to accelerate and focus their research on perfecting DAA systems which do not require expenditure and compliance by everyone else. The confusion of standards (Flarm, P3 – not certified by CAA), Mode-S (poor low-level coverage), ADS-B (bandwidth and monopoly supplier issues), is not helping anyone to make informed judgements, and is costing much, possibly wasted, money in the process.

Whatever EC solution is used, it is crucial that drones MUST prove and confirm functional ADS-B Out before any flight is permitted. Let’s hope the development towards onboard DAA systems on drones and the use of unsegregated airspace continues apace and allows us all to share the finite airspace within the UK.

The bigger picture

This has been a useful first step as a bridgebuilding exercise to co-operate and rebuild some trust and mutual respect with Skyports. Hopefully it is viewed as such, and not merely as a simple box-ticking PR exercise. We extend our gratitude to the team, Harry, Alastair, Nik and Jef for facilitating this and look forward to future co-operation.

There are plenty of drone-related ACPs and more official ‘sandbox’ trials scheduled for the summer (see CAA ACP Portal), but this was a useful ‘road test’ of our EC equipment in a real-time environment, and also gave a better understanding of Skyports operations.

We may think that we are stakeholders as current airspace users, but when you actually read the Drone White Papers and future analysis (follow the links below), it seems quite clear that the real stakeholders are government officials, regulators, drone companies, corporate adopters and investors. GA does not get mentioned.

We should therefore expect, and demand, that our regulator ensures fair play and equal consideration.

Bear in mind that there is a huge amount of government grant money, and political imperative, to support drone operations as ‘the next big thing’, coupled with massive private investment capital – so ‘follow the money’ would be a useful watchword, and I would encourage everyone to read a little more and a little wider.

With the grass-roots/voluntary nature of GA representation, it is a mountainous task for our representatives to keep abreast, and I propose that substantial increased government support and funding for more GA involvement would be a reasonable request.

It is almost impossible to keep up with how many new drone companies, consortia and ventures are being created or proposed, all with associated TDA requests – to name but a few – Trax International Ltd, Nexus Nine Ltd, Electric Aviation Ltd, Skyfarer Ltd, UAVE Ltd, Windracers Ltd, Flylogix, Cranfield, Bristow SAR, Skylift UAV Ltd – everywhere from Orkney to Rugby, from Mull to the Isle of Wight.

Taking Skyports as one small example – in addition to government and ESA funding, there is £8m backing from Irelandia Aviation (backers of Ryanair among others), Levitate, Deutsche Bahn Digital (German Railways) and Groupe ADP (LFPG and LFPO owners).