6 minute read

Maintaining The Florida Trail's Wilderness Sections

by Adam Fryska, Panhandle Trail Program Manager

Advertisement

“A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” - Howard Zahniser

These lines, taken from the Wilderness Act of 1964, described a groundbreaking vision for the conservation of our ever-diminishing wild places. The resulting law created a National Wilderness Preservation System that has designated millions of acres of the most protected public lands in America. These lands are managed with restraint, allowing nature to take its course. Land managers are directed to pursue certain specific goals: examples include protecting watersheds, maintaining native plant and animal species, and providing the public with opportunities to experience a primitive and unconfined type of recreation. To achieve these goals, the Wilderness Act prohibits any motorized equipment or other forms of mechanical transport within protected areas, including the use of power tools for trail construction or maintenance.

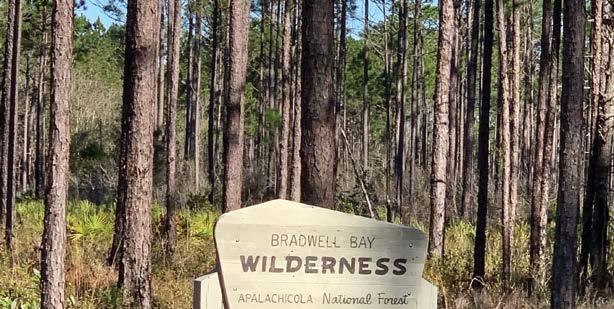

Here in Florida we have 17 federally-designated wilderness areas totaling an area of 1,421,393 acres. These wilderness areas are exactly the types of natural and scenic landmarks that National Scenic Trails seek to highlight. The Florida Trail passes through several of them, including a swampy 12 mile section in the Apalachicola National Forest's Bradwell Bay Wilderness, an 8 mile section in the Ocala National Forest's Juniper Prairie Wilderness, and a 2 mile section along the Port Leon area of the St. Marks Wilderness. Together these areas encompass some of the most interesting and difficult sections of the Florida Trail. Keeping them open and accessible is an ongoing challenge that requires some unique tools and strategies.

Even outside of wilderness areas, trail maintenance along the FT can be very different from the work required on hiking trails in other parts of the country. With its hot and wet subtropical climate, Florida has an almost year-round growing season. In other parts of the world, well-designed hiking trails can go years without requiring dedicated attention from a trail crew; clearing blow-downs and opening drainage features is often the only regular work required. The same approach doesn't work in our environment. FTA’s volunteers strive to thoroughly maintain every single mile of the Florida Trail, every year. If we miss a season, hikers will be stuck pushing through thick saw palmetto and waist-high weeds, struggling to make out the next blaze behind overgrown thickets of titi. If maintenance lapses even longer, the trail tread may disappear completely, swallowed up by the expanding forest. The growth simply never stops. Because of these challenges, we are also uniquely reliant on motorized equipment: mowers, brush cutters, and chainsaws are

Photo courtesy of Adam Fryska

Photo courtesy of Howard Hayes

our day-to-day tools, and we use them to efficiently open and maintain a wide corridor across hundreds of miles of trail.

These maintenance challenges are even more pronounced in federally-designated wilderness areas. As a result of the prohibition on motorized equipment, wilderness trail work depends entirely on “primitive” hand tools. Loppers and handsaws are the primary tools used for clearing encroaching vegetation. Crosscut saws and axes replace chainsaws for clearing blowdowns, and our Suwannee Slings (a kind of manual weed whacker) replace motorized brush cutters for clearing tall grass and weeds from the trail tread. The physical effort required of each crew member is significantly higher. Without the force-multipliers of power tools, we depend on a greater number of volunteers to do the same amount of work, and it always takes longer. Even with our best efforts, these wilderness sections still end up rougher than a more typical section of Florida Trail footpath. In a way, that’s part of their charm; hiking a wilderness trail is an adventure, a chance to venture into one of the few remaining landscapes where human impacts are minimized as much as possible.

A perfect example of this maintenance philosophy can be seen at Bradwell Bay in the Apalachicola National Forest. Bradwell Bay is the longest wilderness section of the Florida Trail, and it has a reputation as being one of the most difficult trail sections. The Bay is one of many wet basins in the forest, a vast titi swamp (a habitat where species of Cliftonia monophylla or Cyrilla racemiflora predominate) with stands of old-growth slash pine, cypress, swamp tupelo, and islands of longleaf pine and wiregrass. Unlike other swampy sections, there is no infrastructure to ease a hiker's journey, no bridges or boardwalks across the standing water. Depending on recent rainfall, the swamp can be anywhere from ankle to waist deep. In winter it’s shockingly cold. Hidden in the dark water are innumerable stumps, branches, and roots, forcing hikers to feel their way slowly and carefully along the route. Since there is no tread to follow, hikers depend on working their way from one visible orange blaze to another. Bradwell Bay is remote and other-worldly; it truly feels like a place where “ man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”

For trail maintainers, the focus in Bradwell Bay is on clearing as much vegetation as possible to ensure an open corridor and clear line of sight between orange blazes. Crews maneuver across the flooded landscape, but instead of using hiking poles for balance, they carry hand saws, loppers, and cans of paint. The pace of clearing the thick vegetation us-

Photo courtesy of Eric Lewis

Photo courtesy of Darryl Updegrove ing hand tools is slow, and it’s helpful to have a large crew; in past years we’ve worked with Student Conservation Association groups and college Alternative Break programs to bring large groups through this area, supplementing the work done by local volunteers. This painstaking process is repeated every year, just to maintain a very basic level of accessibility through the swamp.

If there's a take-home message about Florida's wilderness hiking trails, it's that they require an extraordinary amount of effort to maintain. If you’re interested in contributing to the maintenance of the Panhandle’s wilderness sections in Bradwell Bay and St. Marks, check out the Apalachee Chapter’s Meetup page at: https://www.meetup.com/ Apalachee-Florida-Trail-Hiking/.

For another wilderness opportunity, consider participating in this year's IDIDAHIKE event, hosted by the Apalachee Chapter in St. Marks, FL. IDIDAHIKE is an annual outdoor event and fundraiser for the Florida Trail Association designed to showcase the wonderful and abundant trails in the North Florida Big Bend area; many past events took place along the Suwannee River. Scheduled for February 26 & 27, the event features five hikes (including a trip into the St. Marks Wilderness), a silent auction, education and environment booths, and the chance to connect with hikers and volunteers from all over Florida. FTA volunteers are also needed to help setup and coordinate the event! For more information, see: floridatrail.org/ IDIDAHIKE

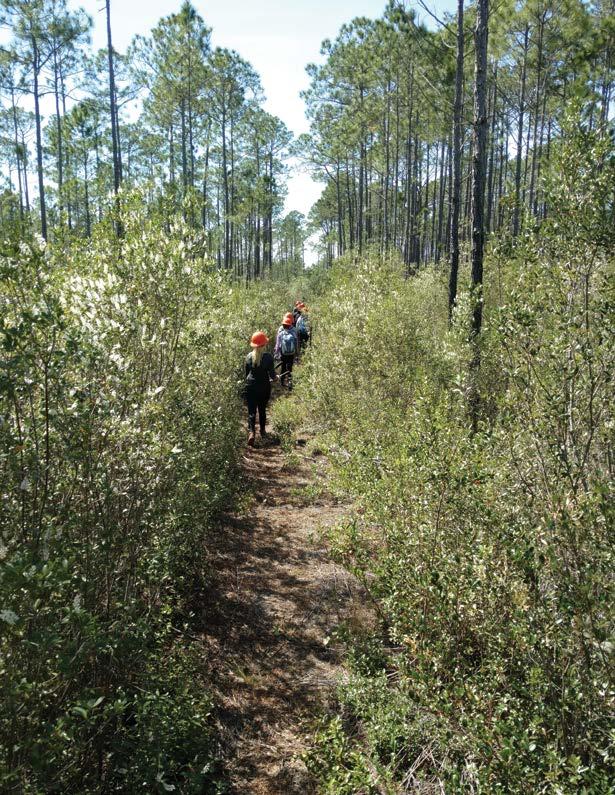

25(Top) The Florida Trail in Bradwell Bay.

25 (Bottom)The entrance to the St. Marks Wilderness, with a warning about primitive trail conditions.

26 Follow the blaze! The primitive trails conditions of a wilderness footpath.

27 (Top) Wilderness areas require proficiency with hand tools.

27 (Bottom) Hikers travel through deep water in the Bradwell Bay Wilderness.

28 Water levels in Bradwell Bay fluctuate from ankle to waist deep.

30 Crews work to cut back the encroaching titi in Bradwell Bay.