8 minute read

Whitehall Society Mixing

It Up

Thursday, March 2, 2023

Doors open at 6:30 pm

Free for Whitehall Society Members

$50 for Flagler Museum Members

$75 for non-members

Mixing It Up is a celebration held in honor of the young professionals of the Whitehall Society. However, tickets are available for all Museum Members and non-members alike. This annual cocktail party supports the Museum’s educational programming for children. The evening’s festivities feature delicious refreshments and live entertainment.

Bluegrass in the Pavilion

Saturday, April 15, 2023

Event begins at 3:00 pm

Performances by The Larry Stephenson Band and Joe Mullins & The Radio Ramblers

$40 per person

The award-winning Larry Stephenson Band has been entertaining audiences for 30 years including their numerous performances on the Grand Ole Opry, RFD-TV and headlining festivals and concerts across the US and Canada. The group is led by Virginia Country Music Hall of Fame member and 5-time Society for The Preservation of Bluegrass Music in America (SPBGMA) Male Vocalist of the year. They also inducted Stephenson into their Hall Of Greats in 2018. With numerous IBMA and SPBGMA nominations and awards, Larry records on his own label, Whysper Dream Music.

Named Entertainers of the Year by the International Bluegrass Music Association (IBMA) in 2019, Joe Mullins & The Radio Ramblers have consistently delivered chart-topping radio hits and energetic performances for nearly 15 years. The Radio Ramblers are seen by tens of thousands of bluegrass fans every year and since 2013 have become regular guests on the historic Grand Ole Opry. Joe Mullins & The Radio Ramblers have generated an indemand following on the national scene, allowing them to be one of today’s most heralded torch-bearers in mainstream bluegrass and gospel music.

A Nearly Forgotten Florida City and its Connection to one of the Great Events in American History

While some historians believe it was one of the three most important events in American history, today few seem to know anything about the World’s Columbian Exposition. One of the many significant and enduring impacts of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition on American culture was the rise of the “City Beautiful” movement and the popularity of Beaux-Arts architecture, even in rather remote locations here in Florida, such as a small community along the St. Lucie River, less than 60 miles north of West Palm Beach. White City, Florida was named in honor of the gleaming, white façades of Chicago’s World’s Columbian Exposition, and its main street, Midway Road, was named after the Fair’s Midway Plaisance. The history of Florida’s White City, however, is an example not only of the enduring legacy of the 1893 Exposition, but also the immense appeal of Florida’s frontier, the wide-reaching influence of Henry Flagler, and the resilience of the human spirit.

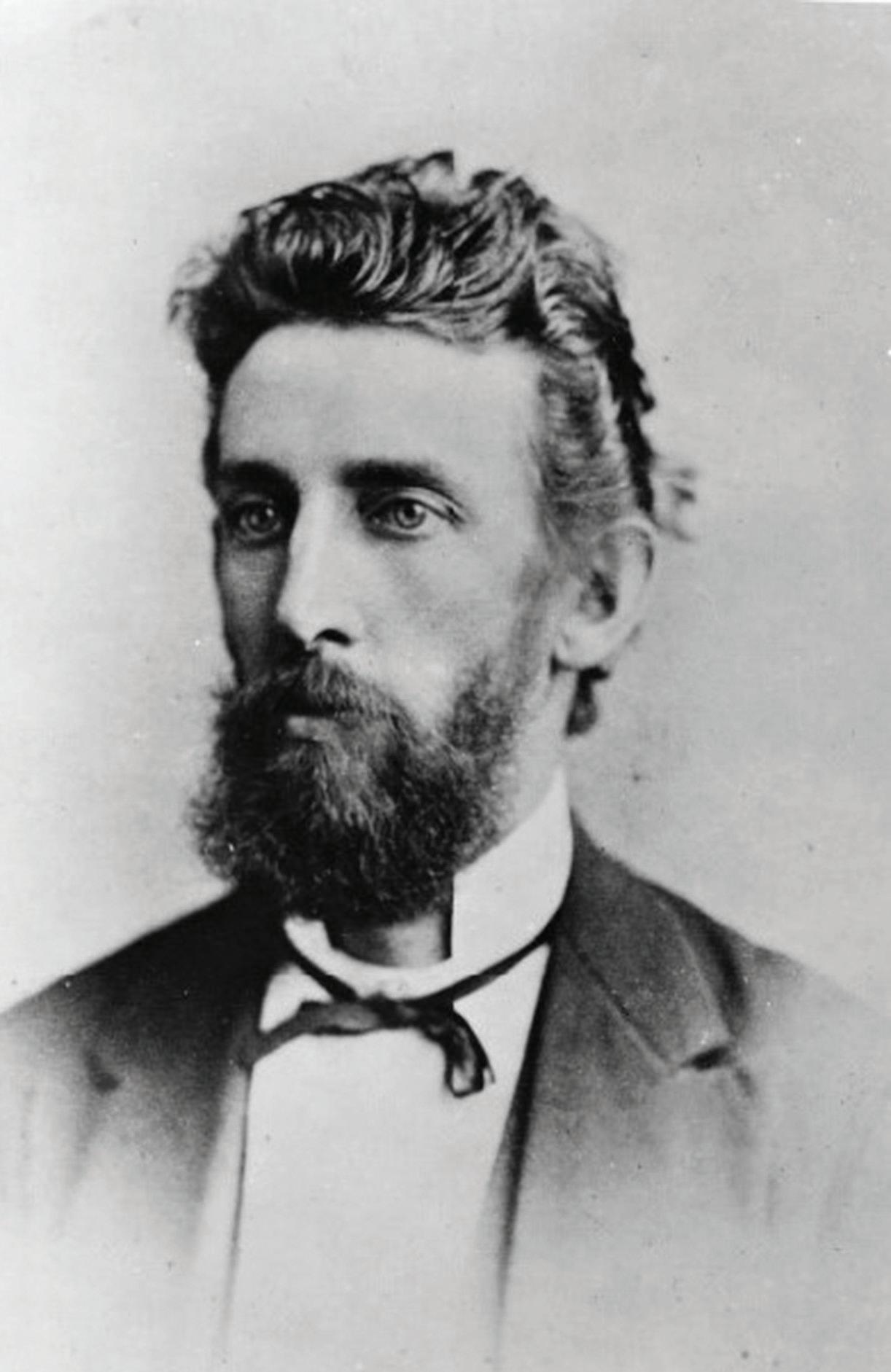

White City was founded in November 1893 by Louis Pio, a Danish journalist, labor leader, and land promoter. Born in Denmark on December 14, 1841, Pio was best known as the editor of the Copenhagen paper, Social Democraten. His involvement in politics and labor organizing eventually landed him in prison, from which he was pardoned by the King after two years, due to his health, and exiled to the United States. Once in the United States, Pio began working to establish a utopian settlement of Danish and German workers near Salina, Kansas. The settlement, however, lasted only six weeks due to lack of funds, insufficient planning, and disagreements between the Danes and Germans. Pio then moved to Chicago and worked a variety of jobs, including: working in a Danish-language print shop, editing and writing for several Danish-NorwegianAmerican papers, and publishing eight books. He also worked as a Customs officer, and finally as a land agent for Niels Christian Frederiksen, a former professor turned magazine publisher turned real estate developer.

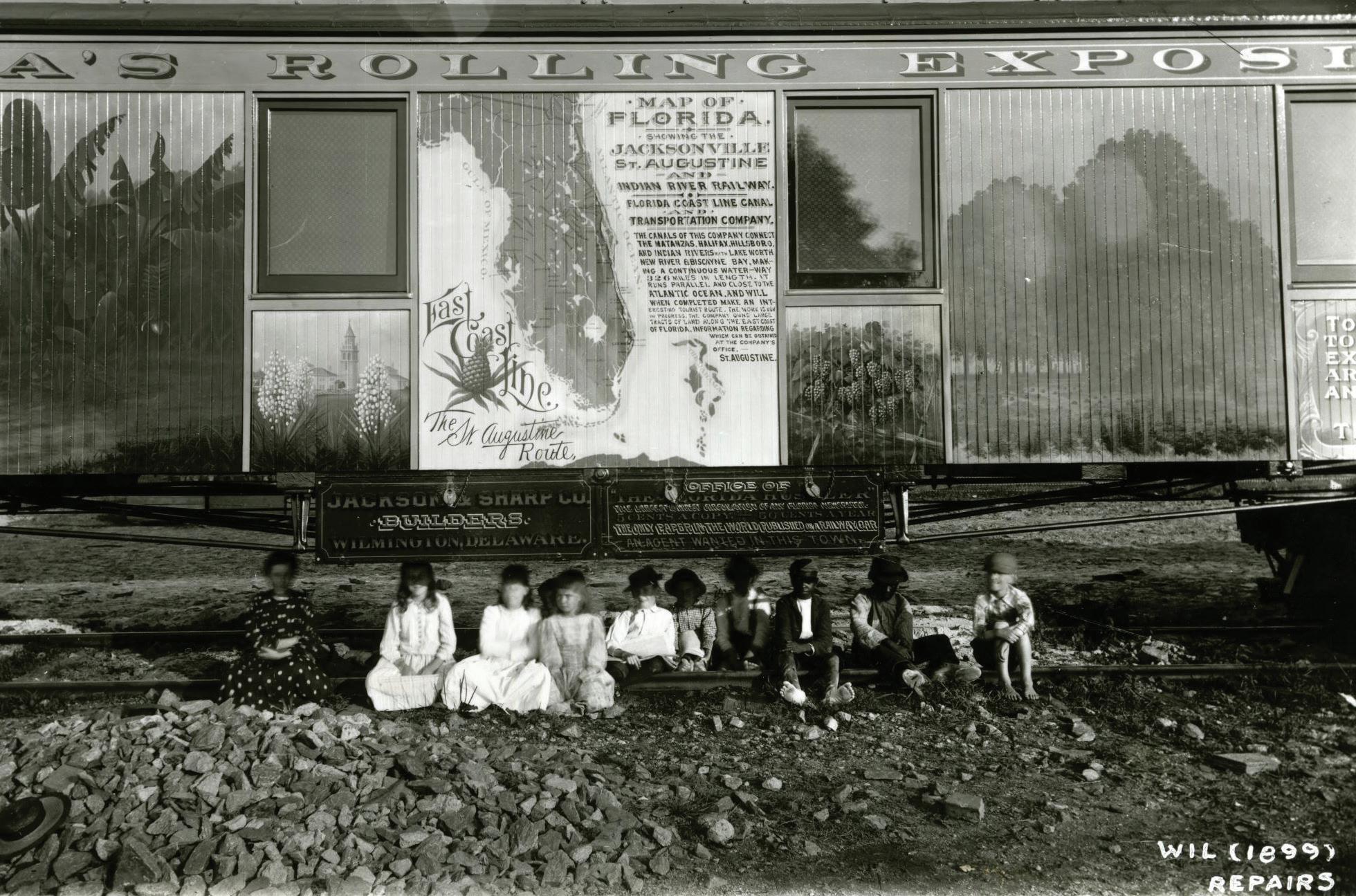

Through his connections with Frederiksen, Pio became involved in other land companies, namely the Florida Coast Line Canal & Transportation Company, the Boston and Florida Atlantic Coast Land Company, and, most importantly, the East Coast Line of the Jacksonville, St. Augustine, & Indian River Railway. Gilded Age Florida was in many ways America’s last frontier. Throughout the 1890s, settlers from the American Midwest and Europe were drawn to Florida, bolstered by the ever-growing reach of Henry Flagler’s railway, the availability of land along the newly constructed lines, and the tireless work of land promoters like Pio. After traveling along Florida’s east coast from December 1892 to May 1893, Pio published The East Coast of Florida: Its Climate, Soil, and Products, a book designed to promote Florida to Danish and English-speaking audiences. He also placed ads in local Chicago newspapers for “Scandinavian workers for railroad and bridge work” on Florida’s east coast, directly recruiting for the Jacksonville, St. Augustine, & Indian River line.

Pio further promoted Florida through an office in the Florida State Building, which Henry Flagler helped fund and where he may well have met Flagler’s son Henry Harkness Flagler, at the 1893 World’s

Columbian Exposition in Chicago, a position that clearly inspired him to develop his settlement in Florida.

From his office in the Florida State Building, Pio distributed “about 50,000 small circulars and 10,000 books to visitors who inquired about Florida,” primarily “Northwestern farmers, especially Scandinavians and Germans.” From the inquiries and connections made at the Fair and throughout the Midwest, Pio organized 23 families to establish the “first Scandinavian colony on the East Coast,” which became known as the White City. By January 1894, 400 people reportedly lived in White City. In addition to his work in bringing Danes to White City through land agencies and promotional materials, Pio’s influence is also apparent in the street names. While the main street was named Midway after the 1893 Exposition, a 1907 map also shows Augusta, Percival, and Sylvia streets, which were named after Pio’s wife, son, and daughter.

While there is no direct correspondence between Pio and Henry Flagler, the Jacksonville, St. Augustine, & Indian River Railway (later renamed the Florida

East Coast Railway) was certainly involved in the development of White City. According to a December 1893 letter from Pio to the editors of The Southern States, the Jacksonville, St. Augustine, & Indian River Railway built an “immigrant hotel” at White City and gave “the settlers very fair conditions for payment.” This included seed, fertilizer, and a weekly stipend until crops were harvested and sold. Despite the relatively small number of settlers living in White City, the rich soil was expected to yield a significant crop of tomatoes, beans, and citrus. Pio, ever the idealist, believed there would be a thousand pioneers in White City before the spring of 1894.

By December 1894, however, multiple tragedies had struck the growing settlement. In spring, Pio and “a companion became lost in jungle-like growth” while trying to establish a road and did not find their way out for several days. Despite the ordeal, Pio immediately left for Minneapolis, Minnesota to meet with potential settlers. In Minnesota, Pio contracted pneumonia and returned to his family in Chicago to recover. However, Pio did not recover and died on June 24, 1894. At the age of 52, Pio left behind a wife, two sons, a daughter, and the White City colony.

Without Pio’s leadership, the colony fell solely under the management of the Florida Cosmopolitan Immigration Company, a land company that had been established by Pio, California rancher Emanuel Jose, and Peter G. Meyer, who served as the company’s treasurer. The company was formally deeded the White City land on March 17, 1894, and that same day the Company filed incorporation documents with the Florida Secretary of State. However, Myer, tasked with managing the colony’s finances, quickly absconded with the settlers’ money after Pio’s death and fled to South America, never to be heard from again. According to historian George Pozzetta, the colonists who, “possessing some monetary resources left the area immediately. The majority, however, were absolutely destitute and had to remain.”

The situation became even more dire on December 19, 1894, when Florida experienced a severe freeze, which destroyed citrus trees and other crops. The recorded temperatures at various stations along the line from St. Augustine to West Palm Beach on the morning of December 19th ranged from 15 degrees to 28 degrees. Suddenly, the impoverished White City colonists were in desperate need of leadership and assistance.

Following the freezes of 1894 and 1895 Flagler, via the FEC land commissioner James E. Ingraham and Florida Coast Line Canal & Transportation Company president George F. Miles, came to the rescue of the White City’s residents, providing money and fertilizer until the settlers could earn enough selling their crops to survive on their own. In 1895 the railroad gifted citrus trees to the community and in 1899 Ingraham sent seeds for Kaffir corn (to be used for livestock) and sugar cane. The Railway and Canal Company appointed Charles Tobin McCarty – the owner of a large lemon, orange, and vegetable grove in nearby Ankona – to manage the colony and advise settlers on climate, soil conditions, and farming operations.

By 1897, Ingraham reported to FEC Vice President J.R. Parrott that there were 70 families residing in White City, writing, “they have now become independent and will after next seasons [sic] crops begin to make payments on their indebtedness. Newcomers are being attracted. Several sales are under way, and the prospects for the colony are encouraging. No advances have been made to these settlers for over a year, and no expenses have been incurred, other than taxes and the care of the Company’s property at this place.”

By 1900, the Florida East Coast Homeseeker described the colony as having more than 500 fruit and citrus trees, 250 head of cattle, and five acres for truck farming.

The ultimate success of White City led to additional Scandinavian settlements in South Florida under the direction and development of the Model Land Company, a subsidiary of the FEC. These settlements included Modelo, a Danish community later renamed Dania Beach, and Hallandale, a Swedish community. And, the “City Beautiful” movement spawned by the World’s Columbian Exposition greatly influenced the design of Whitehall and the design of other cities in Florida, such as Kelsey City, now known as Lake Park.

While few today know about the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, which was designed in-part to celebrate American ingenuity and resilience, its far-reaching influence inspired a nearly forgotten settlement here in Florida named in its honor that lead to the establishment of several of Florida’s better-known cities.

In 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt travelled to Central America to inspect the construction of the Panama Canal. While there, he was given a toquilla straw hat, made in Ecuador, which he wore constantly. Images of the President in his “Panama hat” were splashed across newspapers around the globe. The media and the public couldn’t get enough. The Panama hat became the fashion of the day.

Weaving of the Panama hat can be traced back to 1630, in the provinces of Guayas and Manabi, on the coast of Ecuador. This is the only region in the world where the Carludovica Palm grows. The toquillales are harvested, stripped, boiled, dried, and then weavers from local villages come to choose only the best materials for their craft. The process of weaving a single hat can take days, weeks, or even months. The finer the weave, the longer it takes, the higher quality of hat. Hats are graded and priced based on the number of weaves in a square inch. The process is completed by washing, bleaching, molding, ironing and pressing into the final hat form.

In 2012, the weaving of the Panama hat was named to the UNESCO List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. You can support this tradition by purchasing a genuine Panama hat when visiting the H M Flagler & Co. Museum Store.