7 minute read

A New Frontier for Arborists – Urban Silviculture

BC Fischer, Clinical Professor Emeritus, O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs, Indiana University and Bloomington Urban Forestry Research Group (BUFRG at https://urbanforestry.indiana.edu/)

Introduction

Advertisement

Urban silviculture is a developing/new concept being talked about by urban foresters that arborists also need to understand. It is the adaption of the forestry practice of silviculture to urban natural forest areas, forested patches, or woodlots (hereafter urban forested patches). Silviculture is the theory and practice of controlling the establishment, composition, structure, and condition of forest stands to meet landowner objectives. Historically, it focuses on timber production and other economic and environmental benefits of forests. By definition a forest stand is a contiguous community of trees sufficiently uniform in composition, structure, age, size-class(es), spatial arrangement, site quality, condition, or location to distinguish it from adjacent stands. Larger forests are collections of forest stands.

The practice of silviculture has broadened over the past couple of decades to address a broader range of management objectives rather than focusing primarily on timber with the introduction of ideas such as management for complexity, sustainability, and resilience, as well as management for specific non-timber objectives such as carbon storage, biodiversity, watershed protection, wildfire protection, etc. (1, 2, 3)

Let us examine briefly how urban silviculture may differ from traditional silviculture practices. Urban forest patches are an important component of the tree canopy in cities but are often overlooked by city leaders and decision-makers, and often lack formal management frameworks. One approach to addressing this deficiency may be to borrow from traditional forest management frameworks and practices. Although urban forested patches share similarities with rural forests, the impacts of urbanization on forest stand dynamics may require modification of these methods and in some cases development of novel silvicultural guidelines.

Examples of how urban silviculture differs from traditional silviculture thinking includes the following:

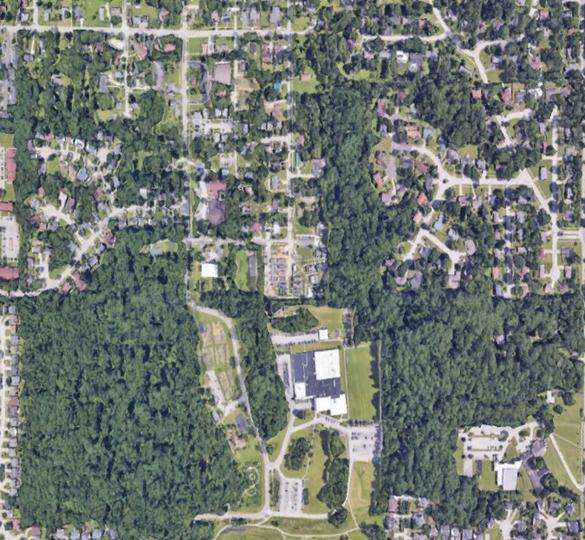

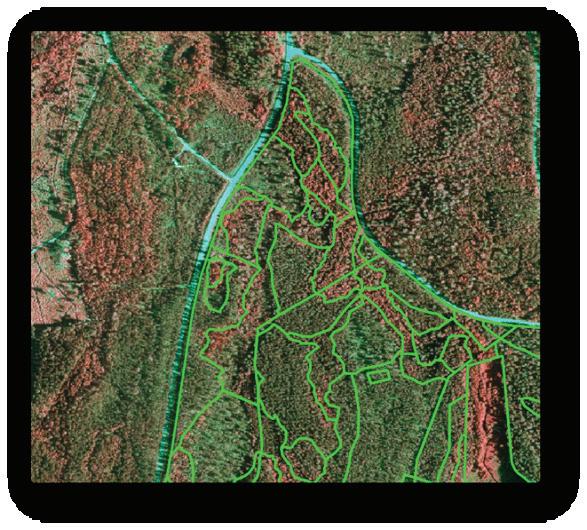

Stands vs patches - Rural forests are typically divided into forest stands to distinguish separate units based upon forest condition and differing site characteristics. Figure 1 is an example forest stand delineation. In urban areas forested areas are small and separated from other forested areas by non-forest spaces, thus each urban forest area is considered a single forest stand. Figure 2 is an example of urban forested patches across several neighborhoods within a city.

Establishment of rural forest stands relies on either artificial (planting tree seedlings) or natural regeneration from seeds, and these regeneration efforts are coordinated with tree harvesting – partial or complete canopy removal. In urban forests tree planting may include seedlings or larger trees (saplings, etc.) in specific targeted locations to increase canopy cover.

Why do arborists need to know about silviculture? Especially in urban forest areas?

I am a forester and specifically a silviculturist by training (forest oriented) and I never think as an arborist (tree oriented) even when I am in the city. So, I think in terms of groups (stands) of trees whether they are in a natural setting, or a park or even just a neighborhood of street and yard trees. In any of these settings I mentally think about the current species composition, structure (one size class, a few size classes, or all size classes), and the condition of the forest. Additionally, what should be addressed next in terms of regeneration (both natural and human-planted), thinning (density management), and structural shifts to better meet the management goals of tree owners or managers moving forward.

A recent article (4) highlights silvicultural thinking about urban forested natural areas and represents a new twist to urban forest management. The article refers to European urban silviculture thinking back to the about 2000 (5), which did not surprise me. There is a long history of urban ecology in Europe focused on urban forested natural areas dating to at least the 1970s.

Simple take home messages for an arborist

1) Recognize that urban silviculture creates a better connection with urban foresters. This can result in collaborative planning, and better communications with the public on benefits of urban forested patches.

2) Identify when urban silviculture needs to be applied. Whether it is an actual urban forested patch, or a neighborhood of trees, managing for species and structural diversity is important to create an urban forest that is resilient to climate change, or whatever other challenges arise. Various roles an arborist might perform in urban silviculture are numerous. Arborists know how to plant trees, whether small or big. There are also tree management tasks arborists address on a regular basis such as pruning and plant health care. Individual or small groups of tree removals to create spaces to plant new tree species to enhance diversity. General tree care to maintain tree/forest quality. Inventory systems and tree inspection systems to monitor the urban forest from a health and risk management perspective. There are many roles for an arborist to play in urban forest management and thinking like a silviculturist can create a positive influence how one addresses the management of a neighborhood’s tree population.

References

1. Puettmann KJ, Coates KD, and Messier CC. 2012. A critique of silviculture: managing for complexity. Washington, DC: Island Press.

2. Fahey et al.2018. Shifting conceptions of complexity in forest management and silviculture. Forest Ecology and Management. 421:59-71

3. Jain T.B. 2017. The 21st Century Silviculturist –Discussions. Journal of Forestry: 117(417-424).

4. Piana MR, Pregitzer CC, and Hallett RA. 2021. Advancing management of urban forested natural areas: toward an urban silviculture? Frontiers of Ecology and the Environment. 2021; doi:10.1002/ fee.2389

5. von Gadow K. 2002. Adapting silvicultural management systems to urban forests. Urban For Urban Greening 1: 107–13.

If in doubt, take a smaller piece

By Dr. Brian Kane, ISA Certified Arborist Massachusetts Arborists Association Professor University of Massachusetts- Amherst

Rigging is one of the most hazardous tasks a climbing arborist does. It involves working aloft, cutting with a chainsaw, and large pieces of wood moving rapidly—sometimes, very close to the arborist. To avoid injuries and property damage, climbing arborists must estimate the rigging loads and predict the movement of the piece once it’s cut.

Few studies have carefully measured loads in a rigging system; knowing what they are and how they change with different rigging tools is essential to maintain safety. If the loads at different points in a rigging system are known, it helps climbing arborists understand how to manage loads to minimize the likelihood of failure of a component in the rigging system, including the tree itself.

We measured tension in the lead and fall of a rigging line secured at the base of a tree and conducted drop tests with different rigging lines (new and used) and blocks (traditional blocks with a rotating sheave and rigging rings). Presumably, a traditional block would offer less friction than rigging rings. When there’s less friction, the load at the anchor will be greater, increasing its likelihood of failure. But if there’s more friction, then a shorter length of line carries the load, increasing its likelihood of failure.

We didn’t find compelling evidence that traditional blocks or rings were preferable. One reason is that the presumption that traditional blocks offer less friction than rings is based on slowly raising or lowering loads, which are not like the “shock loads” that often occur when rigging. If the sheave of the block can’t rotate quickly enough to keep up with the shock load, the rigging line will slide along the sheave, just as does when sliding over rigging rings. The surest way to reduce the likelihood of failure is to rig smaller pieces.

Thank you, Dr. Kane, for your insightful information. You can see Dr. Kane’s TREE Fund webinar from February 2021, “Loading a Tie-in Point While Climbing” HERE and complete a 20-question quiz online for an opportunity to earn CEU credits. For more information and for the quiz link, visit our Webinar Archives page and scroll down to the listing.

Survey to help Canadian TREE Fund

Our friends at the Canadian TREE Fund have teamed up with the University of British Columbia on a survey gathering the opinions of arborists.

A University of British Columbia research project is asking Canadian and American arborists and urban foresters their opinion on research needs in arboriculture and urban forestry and how industry professionals are receiving information. Those who partake in the survey will be entered into a drawing for one of ten gift cards in the amount of $100 CAD each to an arborist supply store. Please consider participating in the anonymous survey by visiting https://ubc.ca1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/ SV_2nTfr0MfT1tIodw. Any comments or questions can be directed to the Primary Contact and Co-Investigator Alexander Martin (arbmarta@mail.ubc. ca) or to the Principal Investigator, Dr. Andrew Almas (andrew.almas@ubc.ca) of the Faculty of Forestry, University of British Columbia

Ride with us at the Tour des Trees this fall

Rider numbers are growing and people are getting excited! Have you always thought about joining us at the Tour des Trees? This is the year to ride!

Join TREE Fund for 380+ miles at this year’s ride from Reno, NV, past Lake Tahoe, and into northern California. Ride dates are September 26 to October 2. This year’s ride is shaping up to be a beautiful, can’t miss event, so add your name to the list today!

For more information and to register, visit www.treefund.org/tourdestrees.

Free Webinars

TREE Fund is proud to partner with the Alabama Cooperative Extension System to bring you free education offerings. We are now able to accommodate up to 3,000 participants!

Tuesday, March 21. 1:00pm CST.

*Note updated day and time

Presenter: Dr. Andy Kaufman, University of Hawaii. Building Urban Tree Resiliency by Mitigating Below Ground Infrastructure Techniques. ISA CEU Credits: BCMA Science: 1; Climber Specialist: 1; ISA Certified Arborist: 1; Municipal Specialist: 1 Register Here

TREE Fund’s 1-hour webinars are free and offer 1.0 CEU credit for live broadcasts from the International Society of Arboriculture and the Society of American Foresters. Registration and information will become available on our website approximately two weeks before each webinar date.

Missed a webinar? Watch it anytime on our website.

CEU Credit for Recorded Webinar

TREE Fund now offers ISA CEU credits for one recorded webinar: “Loading of a Tie-in Point While Climbing.” If you missed this webinar, you can now watch the recording and earn ISA CEU credits by completing a 20 question quiz with 80% accuracy. Learn more on our website.

For more than 75 years, Townsend Tree Service has been helping customers across the country meet their IVM goals by providing world-class service in the following areas:

• Utility, pipeline and transportation line clearing, maintenance and growth control.

• Drainage and right-of-way clearing, maintenance and growth control.

• Storm and disaster emergency response.

• Chemical and herbicide applications. Find out how we can help you.