5 minute read

What are the key ingredients for open innovation success?

Jeremy Basset is CEO of CO:CUBED, where he works with some of the world’s largest

businesses to re-think their organisational approach to innovation, and help them build and execute their collaborative innovation capabilities. Prior to launching CO:CUBED, Jeremy spent 13 years at Unilever where he was responsible for launching and then leading the Unilever Foundry, Unilever’s platform to engage with startups and innovative companies who can help Unilever pioneer the future. Through the Foundry, over 1500 of Unilever marketers have worked with over 150 startups, bringing innovative technology and an entrepreneurial culture to Unilever.

Jeremy Basset CEO of CO:CUBED

According to Jeremy Basset, big companies and startups still have big communication problems, despite growing collaboration among players of all sizes across the food industry. In fact, most of the startups will need a helping hand if they want to make it among the big multinationals – although fragmentation of the industry is squeezing the largest players. On the other hand, even in a business environment now characterised by open innovation and numerous acquisitions, many corporations still struggle to engage constructively. As Basset said:

“There is still an elephant and mouse thing going on here. The language is still quite different, and the time frames are still massively different.” 2

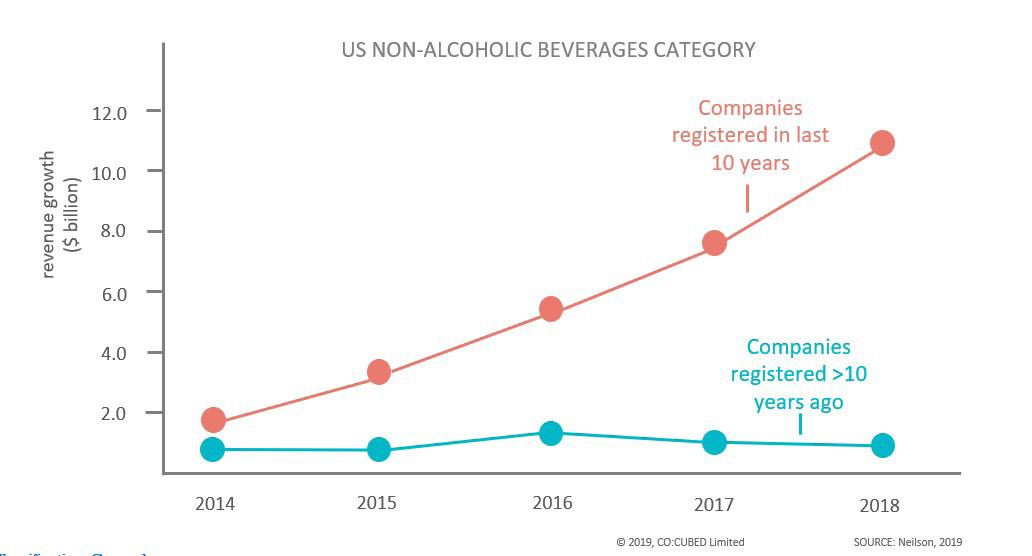

That is to say that, a multinational may be able to take several months – or longer – to get a project off the ground, while that same time period could cause a major cash flow problem for a startup. Basset gave the example of the non-alcoholic beverages category as an area where the big players are struggling to engage. The sector has seen particularly strong growth in recent years – but most major soft drink companies remain outside the trend. Basset added:

“Most revenue growth is going to companies that were registered in the last ten years. This is happening across the food industry and it is happening across every category.” 2

Startups investing in the future

Finding the right balance He suggests that there is a sweet spot for multinationals looking to collaborate with startups, many of which are incredibly optimistic when they start out. At that stage, they are more likely to rebuff a corporate approach, preferring to believe they can make it on their own. A dose of realism tends to come a bit later.

Basset is convinced that partnerships are one of the most effective ways to disrupt the food and beverage sector, but it remains challenging to bring together the scale of big brands with the agility of startups.

“Disruption is interesting and attractive, but disruption is difficult.

…When it works, it works incredibly well. It works for the corporate. It works for

the startup. And, perhaps more importantly, it works for the consumer.” 2

Rahul Shinde is Director Front End Innovation at Givaudan. He is a well-known industry expert and, having worked for a startup himself, he understands all the challenges involved in getting a startup off the ground, as well as the benefits that open innovation can provide, especially in a rapidly changing industry.

Open innovation has become a mainstay in the food and beverage industry over the past decade – and companies have learnt a lot of lessons in the process, sometimes the hard way.

Rahul Shinde Director Front End Innovation at Givaudan

“With the explosion in Venture Capital (VC) funding, it became obvious that open innovation partnerships can be a viable way to source innovation and growth for big companies while supporting and enhancing the ecosystem. It’s almost like a chain reaction, initiated by the startups and enabled by VCs and big corporations.” 3

Staying with the trends Some expensive acquisitions from major companies, helped trigger wider acceptance of open innovation as a concept.

“Coca-Cola, for instance, bought Glaceau Vitaminwater for $4.1 billion in 2007 and in 2015, it acquired a 16.7% share of Monster Beverage Company for $2.15 billion. Coca-Cola launched an open innovation program in 2010 and forged partnerships with startups in emerging categories like coconut water and tea, which enabled it to be part of these trends early on.” 3

Shinde said this approach cost less and created more value for both companies 3 . He added;

“Large companies are realising that a lot of the big ideas are coming from outside, and that they are better suited to start working with the startups earlier in their development cycles for long-term success.” 3

Matching consumer demand While open innovation projects have the potential to accelerate new product development, Shinde warns that consumers have their own pace for experimentation. He gives the example of Quirky, a Californiabased company that aimed to connect inventors with relevant partners to bring new products to market in three to six months. Normally, NPD takes more like two to three years. However, it went bankrupt in 2015. Shinde said;

“They launched product after product and failed to realize that consumers’ appetite for experimentation in mass categories, and home tools & appliances, is limited. Their development costs continued to rise and new products that were supposed to move off the shelf at a rapid pace, did not. This caused the company to crumble.” 3

Quirky has since reinvented itself with new ownership and a new business model.

Regulatory know-how: Challenge or opportunity? From a food ingredients’ perspective, regulation must be a top consideration for any entrepreneur, and it can be daunting. Shinde suggests that this is where partnering with a larger company can create an opportunity, speeding the route to market ahead of potential rivals who will face the same regulatory hurdles.

“It’s food at the end of the day, and you have to follow the regulations properly or you will quickly go out of business. As a startup you probably won’t have the regulatory expertise. But, large companies like Givaudan do. So, you can look at this as a hurdle or as an opportunity. If you look at it as an opportunity, you can leverage the partnership to get a head start towards building a sustainable business.” 3

Collaborate, don’t dictate For food ingredient startups seeking partnerships, there are plenty of other advantages of collaborating with a large company, including access to expertise and new sales channels. Shinde explained that;

“It is important for small companies to play a role in the sales process, even if the partnership is simply about a larger company using their ingredient in a new concept or application. But you don’t just hand over your product and expect them to sell it or use it – you have to be present yourself too. At the same time, startups might feel the need to control the process. That creates a general lack of trust. You have to strike a balance. Approach the engagement through the lens of collaboration and learning.” 3

“Keep it simple at the end of the day. Enjoy the process of creating an innovative product collaboratively, and success will follow.” 3