9 minute read

Standing Up For Silence

from Spring 2020

by FieldNotes

by Allison Phillips and Celine Tang

“Silence is not the absence of something, but the presence of everything,” says Gordon Hempton, an avid soundscape researcher and advocate. Living in Port Angeles has given him the opportunity to spend time in the nearby Olympic National Park (ONP) and to learn about and appreciate its exceptionally unique soundscape. ONP is known to some as the Final Forest or the Last Corner, given that it is one of the last places in the Lower Forty-Eight that was settled by pioneers. It is home to eight tribes and is a World Heritage Site. Some of the last undeveloped coastline in the Lower Forty-Eight is found in ONP, along with some of the biggest Douglas-fir, western hemlock, yellow cedar, and subalpine fr trees in the world. Its extreme weather patterns make for a biodiversity hotspot, including many endemic plants and animals.

With the Park’s natural wonders comes its unique soundscape, encompassing the ocean waves, rivers, birds, bugs, bears, falling trees, and many other natural sounds. Hempton describes ONP as “the listener’s Yosemite”.

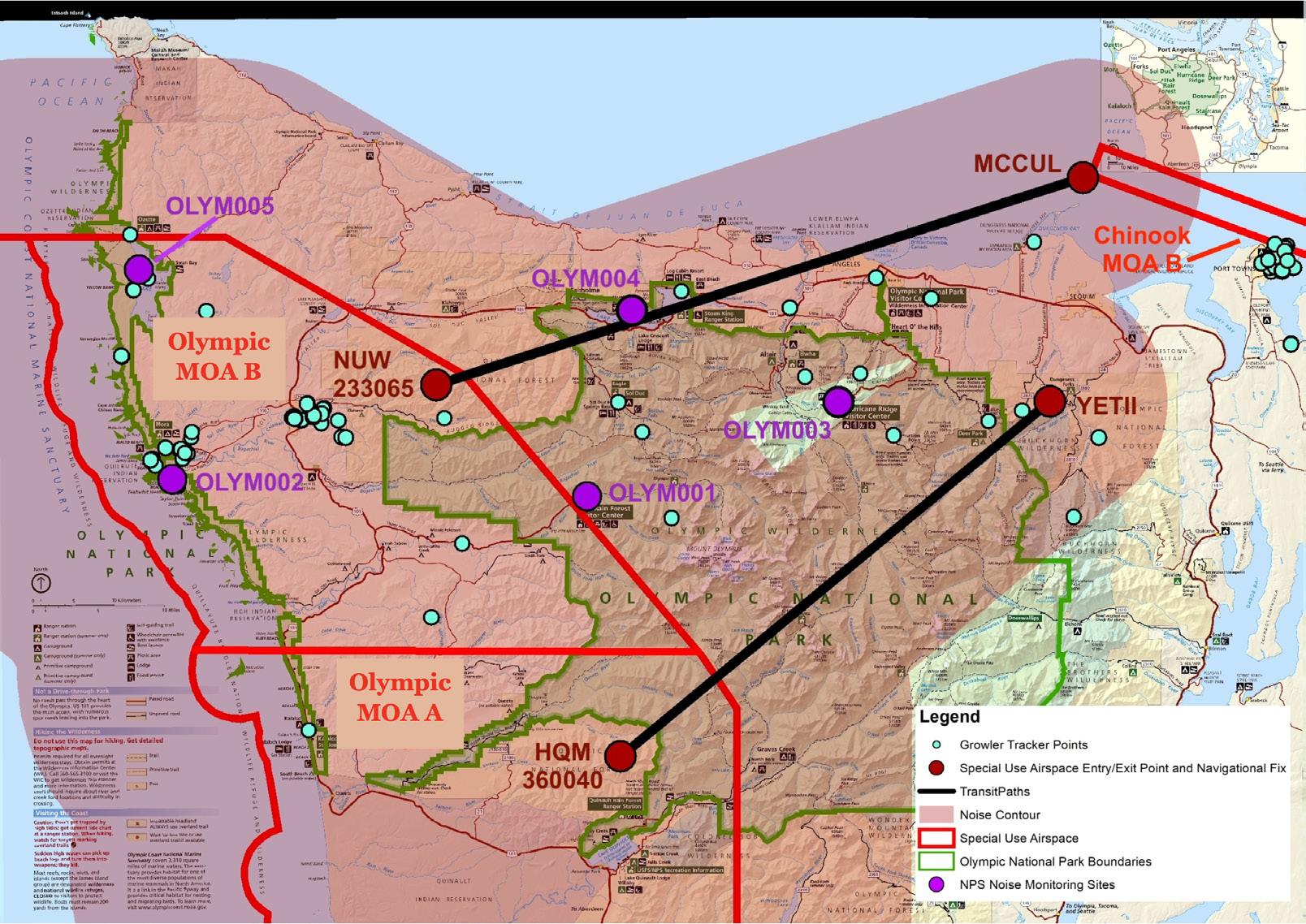

In recent years, however, a newer, more piercing sound has taken flight. Coming from the nearby Naval Air Station Whidbey Island (NASWI), Boeing EA-18G Growlers fy over ONP in the Olympic Military Operation Area (MOA) to conduct pilot training (Figure 1). And as their name implies, they aren’t quiet. As transit occurs between the Whidbey Base and MOAs or training occurs within the MOAs, noise echoes in all directions across the park. Noise from Growlers can vary both in time and intensity; the weekends might not harbor any flights at all, whereas weekdays might bring either a persistent rumble, or intense roars that can prevent conversations and sleep. The flight of a Growler can be heard for yourself here^.

^Listen to Lauren Kuehne’s recording of a Growler flying over ONP by clicking the hyperlink (on our digital magazine) or visiting https://soundcloud.com/user-316341862-466936874/a-june-2017-recording-from-the-third-beach-trail-sound-monitoring-site-as-a-growler-jet-flies-over

Lauren Kuehne, a researcher at the University of Washington, first remembers hearing the roar of Growlers over the campsite she was at on the Peninsula. It was startling to hear them at a popular camping destination in ONP, she recalls, but even more startling that it was before 8am.

A few months later, a resident from Lopez Island of the San Juans emailed Kuehe’s research department inquiring about the impact of Growler noise on wildlife. Kuehne recognized the knowledge gap in this area of study and “realized how much potential this had to change a fundamental character of the region.” According to Kuehne, recording air traffc over the park is important to get a clear distinction between commercial flights and military fights to verify claims by the Navy that military aircraft noise is indistinguishable from commercial flights and is not that loud. Thus, she designed a study to measure the sounds of ONP, and set forth.

Kuehne set up sound monitoring devices in three locations (Third Beach, Hoh Watershed, River Trail) in ONP in June of 2017 and recorded aircraft sounds four times throughout the year, once per season, for two weeks at a time (Figures 2-3). She found that of the 4,768 fight events that occurred, 88% (4,227) were from military operations. To picture this on a smaller scale, in one day the maximum military flights recorded were 79 at the Third Beach site, 81 at the Hoh Watershed site, and 107 at the River Trail site.

To paint a picture of how this kind of sound affects wildlife in the park, Kuehne frst describes what a slight increase in decibels (dBA, measurement of sound) sounds like to us. “Because decibels are logarithmic, an increase in 3 dBA is actually doubling the energy,” she says, “so going from 30 to 33 dBA, a person won’t notice the difference. However, that same 3 dBA change - say, from 70 to 73 dBA - is doubling a lot more energy, and won’t seem at all insignifcant.”

Studies have shown changes in wildlife fitness, vigilance, abundance, vocal behavior, and community structure beginning at 35 decibels. The maximum loudness from aircraft over ONP was measured at over 82 decibels -- these high levels and the large decibel increases from natural ambience have potential to interfere with many species and their activities.

FIGURE 1: Map of MOA and noise contour. Courtesy of the National Parks Conservation Association.

In addition to consequences for wildlife, aircraft noise pollution also has far-reaching effects on people. ONP consists of a pristine natural environment that allows people to experience nature to its fullest. As more of the world becomes urbanized, there are fewer opportunities for people to experience a natural environment. Though it might not be highly noticeable on a daily basis, the constant timbre of sound from a bustling city is an invisible burden. Visitors utilize ONP as a mental or emotional escape. For example, military veterans frequent ONP to experience silence and tranquility, but are oftentimes visited by Growlers overhead, triggering PTSD and damaging their mental health -- especially considering visitation to the park is thought to be a way to escape the sounds of war.

Local communities living on Whidbey Island next to NASWI have also struggled with increasing noise pollution from Growlers. Residents have to structure their whole day around the military’s scheduled flights, as certain activities such as yardwork, studying, or even sleeping are impossible to do. In addition to being a hindrance to everyday tasks, aircraft noise pollution can be a threat to physical health. Many studies have shown that continual exposure to aircraft noise can result in hearing impairment, sleep disturbance, cognitive impairment, high blood pressure, and cardiovascular disease. Due to the Growlers and their associated impacts, two lawsuits against the Navy were fled in 2019 by the citizens of Central Whidbey and the State of Washington. These lawsuits are a reminder that communities need to be considered in current and future Growler impact assessments.

However, there are many in the situation who believe it to be unpatriotic to complain about the consequences of the military’s noise pollution. Many residents on the Peninsula view the air traffic as the “Sound of Freedom.” As one Forks resident wrote in an opinion piece on the Forks Forum, “you would not want untrained people on the police force or firefighters, so why do you continually complain about the training of the Navy?”

Figure 2: Sound-monitoring device in the Olympic National forest.

While true that the Navy needs to train somewhere, proposed solutions do not demand completely shutting down naval operations. Rather, they are attempted compromises to fairly consider all stakeholders in the issue. One such compromise has been to decentralize the noise pollution from ONP. For example, the Navy could relocate part or all of NASWI’s training to the Mountain Home Air Force Base in Mountain Home, Idaho. However, according to the Navy, NASWI possesses ideal flying conditions, the opportunity to train in a coastal region, as well as having access to preexisting military routes. In addition, the Navy claims that conducting their training at NASWI instead of the Idaho base would save about five million dollars each year. In comparison, each Growler costs $68.2 million.

There is a wide array of opinions, in part because every person in this situation is exposed to a different amount of this aircraft noise in their daily lives. People’s varying experiences, personal values, and individual biases have affected their stake in the ONP soundscape issue. As Kuehne describes, “unlike something like air or water pollution, noise is very psychologically-mediated - so people’s reactions to it are incredibly diverse”.

The Navy has indicated that Growler training is essential for contemporary battles, and with this necessity comes increasing demand. In fall of 2015, The Department of Defense issued an additional 36 Growlers to be fown out of the NASWI. Additionally, “there is a proposed increase in Growler training of 62-75% in the MOA starting in late 2020,” says Kuehne, “but without data on current levels, residents, visitors, and land owners/managers have had no real way to evaluate what that increase means.” With an increase in Growlers coming in the near future, monitoring military aircraft noise is essential to measure potential Quantitative results from Growler loudness and frequency, like those produced from Kuehne’s study, provide a basis for discussion moving forward in terms of management, legislation, and other methods to protect the ONP soundscape. Rob Smith, director of the Northwest region of the National Parks Conservation Association (NPCA), works on a multitude of projects that give voice to the national parks, the soundscapes issue being one of them. In agreement with Hempton, Smith notes that information like Kuehne’s study can only go so far. Both mentioned the need for public opinion, personal experience, and legislation. But at the true basis of any of these solutions are trips to ONP itself (or online) to hear with one’s own ears. For Hempton, his personal experience resulted in The One Square Inch project.

The One Square Inch of Silence project is a 1in 2 plot in the Hoh Rainforest of ONP deemed to be one of the quietest locations in the United States. Founded by Hempton in 2005 on Earth Day, his goal was to protect this one square inch in the hopes that said protection would stretch to other areas of the park. His logic was that if anthropogenic noise pollution could affect the landscape so drastically, then so too could the presence of silence. One Square Inch eventually morphed into Quiet Parks International in 2019, which is now an organization dedicated to developing classifcations, standards, testing methods, and management guidelines in order to certify endangered quiet places.

Another vessel for the soundscapes movement is a petition led by NPCA. With a mission to save the wild sounds of the Olympic Peninsula, NPCA aims to educate the public about the military’s threat to the quiet landscape. The goal of their petition is to urge the U.S. Navy to move their operations to navy bases with less vulnerable ecosystems.

The combination of research, public experience, and public opinion creates the opportunity for legislation to gain movement. Kuehne, Quiet Parks International, and NPCA are among the many facilitating changes to put pressure on government entities. With the loss of a crucially vital soundscape and subsequent ecosystem at hand, it’s time to speak up for silence.

“Do not listen to me as the voice of nature or of silence,” says Hempton, “simply go to a quiet place in nature. Go listen for yourself.”

Figure 3: Lauren Kuehne setting up a sound monitoring device in the forest.