8 minute read

THE THIRST FOR BLOOD

Has our fascination with the supernatural warped our perception of bats?

From terrifying monsters to teen heartthrobs, our society has been in awe of vampires for hundreds of years. Popular culture is continually transforming our perception of what a ‘vampire’ is and yet one constant theme is the everlasting thirst for blood. This narrative bleeds into science, as some species exhibit hematophagy, the practice of feeding on blood.

Advertisement

Hematophagy

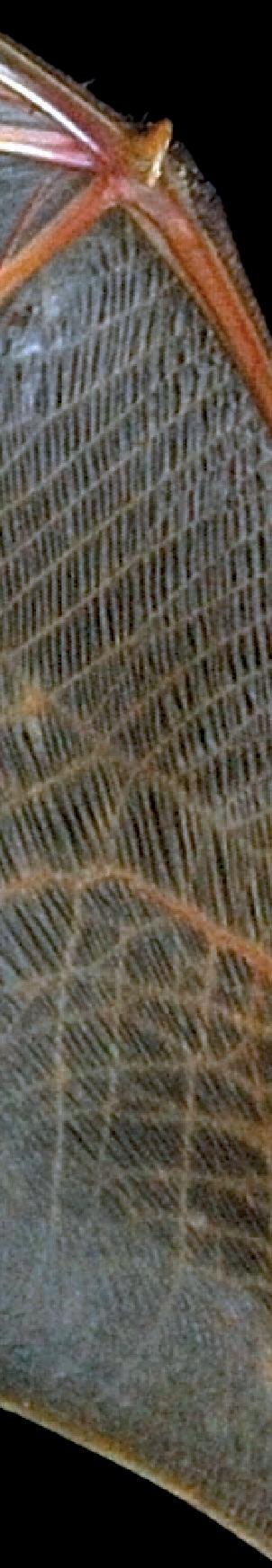

There are three species of vampire bat, all residing in Latin America. Of these three, only Desmodus rotundus has been known to feed on mammals. However, all three evolved from fruit-eating bats and developed a very rare taste for blood. The practice of feeding exclusively on blood is generally uncommon in the animal kingdom, rare amongst vertebrates and practically unheard of within mammals. Of course, the vampire bats break this trend.

Blood is around 93% protein. Yet, it is less than 1% carbohydrates and very low in nutrients. Furthermore, there are countless blood-borne pathogens and bacteria that can be found in blood. In fact, after carrying out a full hologenome analysis, researchers found that the droppings of D. rotundus contained over 280 bacteria known to cause disease in other mammals (M. Mendoza et al 2018).

This led the team of researchers to explore what it is that allows the common vampire bat to thrive on a sanguivorous (blood-based) diet. The paper reads “it is clear from our results that the common vampire bat has adapted to sanguivory through a close relationship between its genome and its gut microbiome.” These findings may represent a bigger picture for how we study the adaptations of all animals. By failing to consider the gut microbiome when looking at genetics, we fail to paint a true picture of how that adaptation came to be.

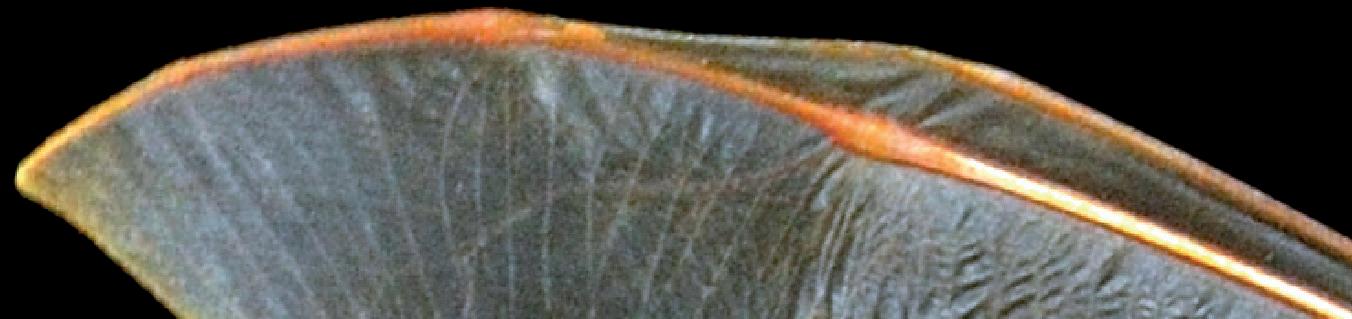

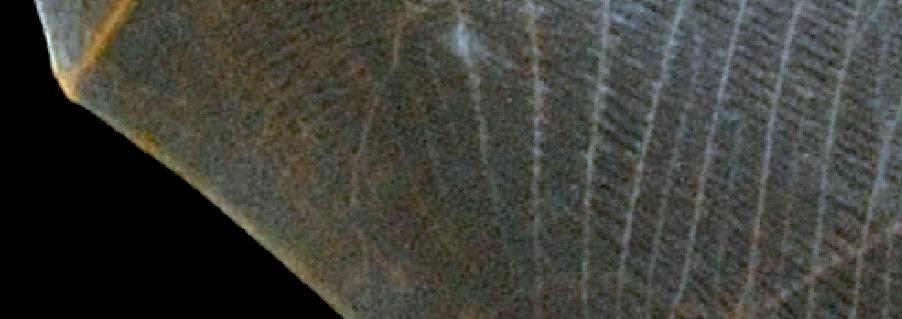

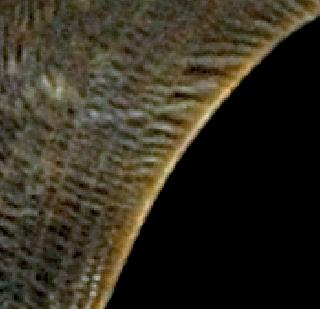

One myth that surrounds vampire bats, is their method of drinking blood. In fact, there are some similarities with the fantasy stories of ‘blood-sucking’ humanoids from Transylvania. Vampire bats will create an incision on their prey (often large hooved stock that rarely feel it) with their teeth, then proceed to lick this with their tongue. It is quite common to hear that vampire bats ‘don’t suck blood, they lap it up’, yet this is not entirely true either. Both Desmodus and Diaemus have capillaries within their tongues, which creates a groove that can ‘suck’ blood. A feed can last anywhere up to 30 minutes, with the tongue touching the wound/blood flow up to 900 times before the unsuspecting victim wakes up. Not all feeding is done whilst the prey is asleep, with cumbersome mammals such as sea lions, being harassed throughout the night before the bats get their feed.

To access the most subtle or poorly defended areas of their prey, vampire bats have developed the ability to walk and jump which is generally unusual for bats. They will land close to their victim before quietly sneaking up to them from a nearby ledge.

For all their gruesome traits, common vampire bats could be considered generous animals. Their nutrient and carbohydrate-poor diet mean that feeding every night is an absolute necessity. One night without blood can be fatal to a vampire bat. Therefore, these animals will regurgitate blood to share with other bats if they have had an unsuccessful night. Colonies are comprised of up to 100 bats that will groom each other after returning from a feed.

Bats and disease

Bats have been the media focus of many zoonotic diseases in recent years. While they pose almost no risk to humans here in the UK, rabies is a prominent disease in the tropics. In Latin America, particularly Brazil, battransmitted rabies is on the rise. With major efforts to control the spread of dog-transmitted rabies since the 1980s, the number of bat-transmitted cases exceeded those transmitted by dogs in 2004 and increased ever since. In fact, 2005 saw just 13 cases of dogtransmitted rabies, compared to 60 cases of bat-transmitted cases.

Wilson Uieda is a Professor of Zoology at Sao Paulo State University and leads the Bat Conservation Programme of Brazil. He states, “the problem of humans being bitten by vampire bats and thus at risk of rabies transmission has existed in Latin America for centuries, although recently there have been increased reports of human rabies transmitted by the common vampire bat D. rotundus, especially in the Amazon regions of Brazil and Peru.”

Riverine communities, particularly those that sleep in open hammocks within open wooded houses are at an increased risk of being fed upon by D rotundus

Feet and toes tend to be the most common area to be bitten, but some instances of bites upon the face have occurred. Naturally, this can lead to significant trauma and scarring.

“A study of those outbreaks, for which a report was published with information on where they occurred, shows that most of them shared the same conditioning factors. We divide these factors into two interrelated groups: biological and nonbiological. Biological factors include the presence of vampire bats, the existence of adequate shelter for them, the availability of food sources, and the presence of rabies virus in the area. Nonbiological factors include the type of human productive process and changing patterns in such activities, working and living conditions, access to rabies prophylaxis (medication), and measures being implemented to control bat populations.”

As the name suggests, common vampire bats are abundant throughout Central and South America, with population numbers on the rise, largely fuelled by agriculture. In well-preserved forests vampire bats are rare. This is because most South American mammals have some nocturnal behaviours, making feeding difficult for the bats. The hunting of wild mammals in these areas also reduces bat population numbers. Where there is more domesticated livestock, there are more feeding opportunities as well as nesting areas for the bats.

Although bat-transmitted rabies is a genuine risk in South America where vampire bats live, our native species here in the UK are entirely insectivorous. Furthermore, the UK is regarded as a ‘rabies free’ country. Whilst stories of blood-sucking vampires can inspire some wonderful areas of study and unearth some truly fascinating aspects of natural history, the misinformation surrounding it can negatively impact vital conservation efforts.

Alex Morss, Communications Officer at the Bat Conservation Trust reassured us: “A very small number of bats in the UK have been found to carry rabies type viruses called European Bat Lyssaviruses (EBLV). EBLV are not the classical rabies virus that is usually associated with dogs. Classical rabies has never been recorded in a native European bat species. There has only been one known human case of EBLV in Britain in the past 100 years. The presence of EBLV in bats in the UK does not affect the UK’s rabies-free status as this relates to classical rabies only. Bats are not normally aggressive and will avoid contact with humans. This means that there is no risk if you do not handle bats.”

Although much of the rhetoric surrounding bats in mainstream media recently has been negative, awareness campaigns explaining their role in our world’s ecosystems are also growing. Despite countless challenges brought on by disease, the threat of climate change and the importance of preserving biodiversity is becoming much more well-known.

Alex continued: “Bats play vital roles in ecosystems. In tropical countries, many plants and crops rely partly or wholly on bats to pollinate their flowers or spread their seeds. European bats feed mainly on insects. This brings many benefits to humans, like helping to control insects, some of which can damage crops and gardens and carry diseases such as malaria. Studies have shown that bats save farmers billions of dollars in pest control every year as they are prolific insect eaters. They are also vital as seed dispersers and reforesters. Their poo, called guano, is also valuable as fertiliser.”

“Bats are important indicator species that tell us about the health of the environment. They are vital pollinators for at least 500 plant species, including many foods that we love, such as mango, banana, durian, guava and agave [which is used to make tequila). Many of the foods in our kitchens are either provided by or grown with help from the roles of bats.”

Britain’s bats

Although vampire bats do pose a very real threat of disease transmission in developing countries, particularly in South America, this fearmongering has created new challenges for conservationists working with bats across the world. In fact, it is much more likely that our actions pose a greater risk to bats, than the other way round.

Alex Morss, Press and Communications Officer at the Bat Conservation Trust told Exotics Keeper Magazine “There are some big misunderstandings around bats, particularly on diseases. Sadly, this has resulted in bats being unfairly persecuted in several countries. It is important to dispel widespread unfounded fears and myths about bats because it directly threatens their conservation, and bat persecution can also have wider impacts on people and other wildlife.”

“Recent research has shown we increase the risk of zoonotic disease-carrying pathogens crossing species barriers into humans when we destroy or degrade natural environments, exploit, stress or destroy ecosystems and their wildlife.”

Here in the UK, there are 18 species of bats a`s well as one Greater mouse-eared bat (Myotis myotis) that has been discovered in the South of England, since it was officially described as extinct in 1990. All species have previously seen population declines and misinformation and fear has accelerated this. Now, with protection at governmental level, things are starting to change.

Alex explained: “One of the biggest threats to bats is habitat loss. This can be subtle because they are a cryptic, nocturnal species and we don’t often see or hear mammal species and nearly 25% of British mammal species. [1,400 species worldwide; 17 breeding species in Britain]. We monitor trends for 11 of our 17 species. The good news is that in the UK, we appear to be seeing slow recovery them in many parts of the world, so it’s easy to overlook them when they are roosting quietly in trees or buildings. Those hidden roosts are vital and legally protected bat habitats. For this reason, to protect bats and follow the law in Britain, it is essential to seek advice from a suitably qualified bat ecologist before carrying out building work or tree removal that might harm them. In Britain, all of our 17 breeding bat species and their roosts are legally protected. No-one should be handling or disturbing bats without first having training and a licence, so all those who do, will be doing so safely following good practice, for themselves and importantly for the welfare of the bats. “

“It’s worth remembering that bats make up over 20% of the word’s following decades of decline last century, thanks to better wildlife protection laws and practices. Our National Bat Monitoring Programme reveals population trends for 11 breeding bat species. All of them are considered to have been stable or to have increased in the last 20 years.”

“However, some other British bats remain at risk, and globally we don’t have enough data on all 1400 species to be able to protect them. In Britain, for example: the grey long-eared bat is endangered; the barbastelle bat and serotine bat are both considered vulnerable; the Leisler’s and Nathusius pipistrelle are both near threatened. We don’t yet know the conservation status of several others because of too little data, including the Alcathoe bat, Brandt’s bat and whiskered bat.”

Exotics enthusiasts know all too well how misunderstood our beloved reptiles, amphibians and invertebrates are and bats are no different. With the correct protection laws being put in place, as well as a shift in public attitudes, hopefully bats across the world will be better understood and appreciated for their ecological significance.

Alex concluded: “Bats are amazing, and many are also threatened, so they need our support more than ever. I am in awe of them, no-one who understands them and how incredible they are, how gentle and harmless they are, and all of the benefits they bring, could fear them. Bats are lovable and appreciated by anyone who takes the time to watch or listen to them or understand how amazing they are, as well as all the benefits they bring to people and ecosystems.”

More information on how to support native bats and get involved with their conservation can be found here: https://www. bats.org.uk/support-bats