3 minute read

CHYTRID FUNGUS AMPHIBIAN CRISIS

Amphibians are currently facing what is possibly the most catastrophic crisis in their evolutionary history. Presenting many parallels with the COVID-19 pandemic, a devastating fungal disease has spread worldwide.

Advertisement

Chytrid Fungus Amphibian Crisis

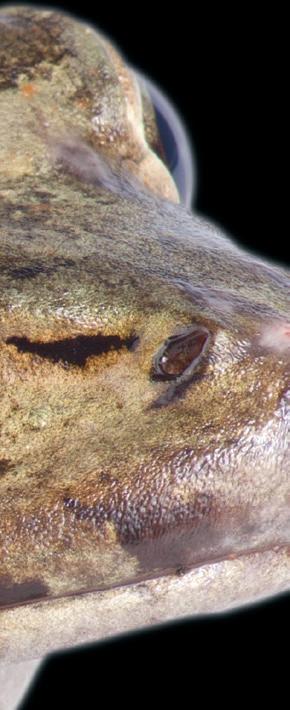

Chytridiomycosis is a disease that attacks amphibians’ moist skin and is responsible for the decline of over 500 species. Although it has been known to scientists for decades, the impact of a new pathogen which is lethal to some salamanders could spell disaster for some of Europe’s most iconic amphibians. While deforestation and climate change are major drivers of extinction at present, amphibians are also threatened by the suite of virulent pathogens that cause Chytrid. To understand the scope of the amphibian crisis, we spoke with Benjamin Tapley, the curator of herpetology at the Zoological Society of London (ZSL).

Benjamin Tapley, Curator or Herpetology at ZSL

As curator, Ben ensures that the collection of reptiles and amphibians at London Zoo is comprised of the most significant priority species relevant to the conservation aims of ZSL. In addition, Ben works on conservation projects in the field, and much of his work is focused on Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered (EDGE) species.

Ben has mentored and trained others in the field to work with amphibians, monitor their pathogens, and maintain healthy captive collections for conservation purposes. This is extremely important particularly for species that will be translocated at a future date back into their natural habitat to establish new breeding populations. These translocated animals need to be physiologically and genetically healthy for the program to be successful.

Pandemic Parallels

Since its discovery in 1998 there have been significant developments in the Chytrid saga. Although some success stories have surfaced, the picture remains very bleak. Ben explained: “In a snapshot, these pathogens pose a major conservation challenge, there are no pathogens comparable to them in terms of the number of species they infect and their global range; their impact as drivers of biodiversity loss is unparalleled.”

A review from the academic journal Science in 2019 stated that the disease chytridiomycosis was a factor in the decline of at least 500 species of amphibian in the last 50 years, and declines >90% in more than 100 species. Alarmingly, the study also presumed ‘extinction in the wild’ of 90 amphibian species as a result of the disease.

Chytridiomycosis is caused by amphibian chytrid fungi. Scientists have known about one of these chytrid fungi, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (often abbreviated to Bd) for decades. In 2013 another chytrid was identified as causing population declines in European salamanders. This chytrid, Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans (Bsal for short) is likely to have originated from East Asia. Chytrid mediated declines have not been reported in Asia and it is now thought that chytrids originated from this region and that global trade facilitated their spread around the world. These pathogens are likely to have spread via the trade of laboratory animals, or via stowaway amphibians from other regions hitching a ride in cargo, like food, and finding their way into the environment. There is also concern around wastewater being introduced into the environment from captive, non-native amphibians.

Chytrid fungi can infect a wide variety of host species; some

FACT FILE: BATRACHOCHYTRIUM DENDROBATIDIS

DESCRIBED: IN PANAMA AND AUSTRALIA, 1999, BY LEE BERGER

CONTINENTS AFFECTED: NORTH, SOUTH AND CENTRAL AMERICA, ASIA, AUSTRALIA, AFRICA, EUROPE

EXTINCTIONS: 90+

SPECIES AT RISK: VIRTUALLY ALL FROGS, TOADS AND EVEN CAECILIANS; HUNDREDS OF SPECIES IN DECLINE WITH BD AS A LIKELY CONTRIBUTOR

MODE OF TRANSMISSION: CONTAMINATED WATER/MOIST SURFACES; DIRECT CONTACT

INCUBATION TIME: 14-70 DAYS

SYMPTOMS: RED/DISCOLOURED SKIN, LESIONS, ABNORMAL BEHAVIOUR/LETHARGY/POSTURE, SUDDEN DEATH

TREATMENT: ANTIFUNGAL BATHS, HEAT TREATMENTS, SODIUM CHLORIDE

PREVENTION: ISOLATION asymptomatically. These species may act as reservoirs of infection that facilitate the spread of the pathogen in their environment.

“Susceptibility does vary between species, and it may even vary between life stage as well,” Ben commented. The zoospores of the fungus are motile in water and require cool, moist conditions to survive. Amphibian skin works in complex ways to allow respiration, thermo- and osmo-regulation. Chytridiomycosis disrupts the water and mineral balance of diseased amphibians. This results in death, normally because of electrolyte imbalances that lead to heart failure.

Working with threatened amphibians

Ben has been working with Leptodactylus fallax, otherwise known as the ‘mountain chicken’ frog (which does indeed get its name for culinary reasons) for 15 years. This species exhibited one of the most rapid declines documented in a vertebrate after chytrid fungi arrived on the eastern Caribbean islands of Dominica and Montserrat. More than 80% of the population was lost in just 18 months, with the species thought to be extinct in the wild on Montserrat. To combat this, a captive breeding project was established for future reintroduction of the species to Montserrat as a result. Sadly, there are only around 100 individuals remaining in Dominica.

Ben was also part of a team that documented the first known case of lethal chytridiomycosis in a caecilian amphibian and went on to develop a treatment with veterinary colleagues at ZSL London Zoo. Caecilians are limbless amphibians and the majority of species live underground which means that they are rarely encountered and poorly studied.

Another example of a species that has been dramatically affected by Bd is the Panamanian golden frog (Atelopus zeteki). In addition to being threatened by the loss of habitat and the impact of climate change, in 2004 chytridiomycosis ripped through the local population very quickly. The IUCN currently lists this species