9 minute read

Life Beardie

A blended substrate to help create the ideal enviroment for Bearded Dragons and other desert species.

Advertisement

Up close with crocodiles

Crocodiles of the World reptile inventory

Alligators

American Alligator Alligator mississippiensis

Chinese Alligator Alligator sinensis

Spectacled Caiman Caiman crocodilus

Yacare Caiman Caiman yacare

Broad-snouted

Caiman latirostris

Black Caiman Melanosuchus niger

Dwarf Caiman Paleosuchus palpebrosus

Smooth-fronted Caiman Paleosuchus trigonatus

Crocodiles

Nile Crocodile Crocodylus niloticus

Saltwater Crocodile Crocodylus porosus

Siamese Crocodile

Crocodylus siamensis

West-African Dwarf Crocodile Osteolaemus tetraspis

West-African Slender-snouted Crocodile

Mecistops cataphractus

Cuban Crocodile Crocodylus rhombifer

Morelet’s Crocodile Crocodylus moreletii

Philippine Crocodile Crocodylus mindorensis

West African Crocodile Crocodylus suchus

Tomistoma Tomistoma schlegelii

Australian Freshwater Crocodile Crocodylus johnstoni

Lizards

Komodo Dragon Varanus komodoensis

Lace Monitor Varanus varius

Crocodile Monitor Varanus salvadorii

Emerald or Green Tree Monitor Varanus prasinus

Black Tree Monitor Varanus beccarii

Ridge or Spiny-tailed Monitor Varanus acanthurus

Asian Water Monitor

Varanus salvator

Merten’s Water Monitor Varanus mertensi

Argentine Tegu Salvator merianae

Giant Day Gecko

Yellow-headed Day Gecko

Phelsuma grandis

Phelsuma klemmeri

Caiman Lizard Dracaena guianensis

Crocodile Skink

Snakes

Tribolonotus gracilis

Royal Python Python regius

Green Anaconda Eunectes murinus

Boa Constrictor

Boa constrictor

Reticulated Python (Malayo) Python reticulatus

Green Tree Python Morelia viridis

Chelonia

African Spurred Tortoise

Galapagos Tortoise

Red-foot tortoise

Centrochelys sulcata

Chelonoidis nigra

Chelonoidis carbonaria

Leopard Tortoise Stigmochelys pardalis

Fly River Turtles

Amazon Giant River Turtle

Carettochelys insculpta

Podocnemis expansa

Alligator Snapping Turtle Macrochelys temminckii

Staying Safe

If we’re in an enclosure with a big specimen then there’s a very low tolerance for risk. At the slightest sniff of something looking a bit hairy we have a robust ‘run away quickly’ policy. We don’t take risks with anything which could be truly dangerous.

The sharp end

Yes, of course, I have been bitten by a crocodile, but thankfully only small ones. Everyone who works with animals has been bitten! The worst bite was, predictably, a Cuban Crocodile (Crocodylus rhombifer) – a particularly snappy species, which I was handling as part of a display. It wasn’t large, four feet long or so, but it was one of those days where I just wasn’t on my top game. My handling was a bit lame so the croc seized its chance and spun to get away. The croc’s tooth skimmed my thumb during the process and sliced it open.

Under different circumstances I would have just dropped the animal and the drama would have been over and done with, but with a dozen school kids around me, that wasn’t an option. So I just held onto it! This was one of those situations where I knew I wasn’t really in the mood – and the croc wasn’t in the mood either – so we should have just called it off. But I was in the mindset that the show must go on, and that’s how accidents happen. I ended up with a few stitches and a decent scar.

My worst bite ever was from a 35kg wombat I was measuring when I was in Australia. That little bugger bit me and left a chunk of flesh flapping on my forearm. It wasn’t very nice at all.

Up close with crocodiles

Breeding crocs

Before we breed anything we have to be sure that there’s a need for those babies and a purpose for the breeding. We have to work out what we want to breed, how many, and where they’re going to go if they do breed. For example, the only outlet for dwarf crocs (Osteolaemus tetraspis) is the pet trade, so that’s not really an option.

Similarly, we rarely breed Siamese crocs (Crocodylus siamensis) even though they’re critically endangered, simply because there’s nowhere for them to go if we do breed them. You can’t just send them back to the wild in Cambodia because there’s no habitat for them there. Breeding this species will make no difference to their endangered status.

There have been situations where zoos have bred critically endangered species and then, a few years later, the whole zoo community worldwide has to stop breeding them. There’s nowhere for the animals to go because zoos are overrun with them. It sounds crazy, and it is. That’s how endangered croc species, such as Philippine crocodiles (Crocodylus mindorensis), end up in the pet trade. Our entire breeding efforts are dictated by what we need and the needs of other zoos.

Thankfully the Natural History Museum is running a project that can make use of unhatched croc eggs. So if we get eggs from a species where there’s no outlet for the babies then the Museum is happy to take them off our hands.

Rebecca And Hugo

Rebecca and Hugo are some of the stars of the show at Crocs of the World.

Siamese crocodiles are critically endangered in the wild, with their population decreasing. Thankfully, Rebecca and Hugo mate each year at Crocs of the World, with any hatchlings from their clutch going to other zoo collections around the world.

Getting the eggs to put them in the incubator can be fun! Siamese crocodiles are very protective.

Up close with crocodiles

Crocodile pets

There’s lots of debate about whether crocodiles, and particularly endangered species, should be sold to private keepers. There’s no black or white answer to that question as some people keep them well and some people keep them badly. Of course, I support those who do it well and I despise those who keep them badly.

People who get a croc for bravado and ego are often the ones who cause problems. On the other hand, I know plenty of private keepers who could, and would, happily work in a zoo if it paid well. Instead, they keep these animals privately and dedicate significant time, money and resources to their husbandry – often far more than can be done by any zoo.

These dedicated specialists can often know more than the generalist zookeeper. And, of course, there are crap zoos and crap zookeepers out there too. I’m certainly not against private croc-keeping in general. I’m against bad croc-keeping.

At the end of the day, crocs aren’t a sensible choice if you want a pet, but sensible and responsible private keeping is a different matter. It’s the same for people who keep venomous species or large snakes and lizard species, or any animal for that matter. If you’re sensible, we’re on your side.

Banning animals from private ownership has been a disaster everywhere it has been introduced. In Australia, a place with some of the strictest wildlife laws in the world, you can still get corn snakes and anacondas if you want them.

While buying from breeders isn’t a bad idea, few breeders are regulated, licensed or inspected – unlike pet shops. In reality, many shops will sell you a reptile five minutes after the store closes in the car park. It’s crazy to make selling reptiles so difficult as it sends the trade underground. You can’t get expert help or vet treatment for an animal you’re not supposed to have. At least if the trade is legal and regulated the authorities can monitor and understand what’s going on, and the keepers and animals can have access to the resources, advice and treatments they need.

Banning people from keeping crocs, or indeed any animal would be a bad idea. People should be allowed to keep any animal as long as the regulations enforce good husbandry and welfare.

How to handle a croc

Well. The first task is to decide whether you do actually need to move or handle the animal and, if you don’t, then don’t do it. If you do need to move it, then there are several ways to go about it.

Anything under 4ft is a quick job for someone with the necessary experience – you just jump on and pick it up. That said, you do still have to be careful. Any croc approaching 2ft is going to give you an unpleasant bite. And you really don’t want to be bitten by anything approaching 3ft. A fourfooter isn’t going to tear bits off, but it’ll be a messy affair and it will cause you some real problems if something that size bites you. Anything bigger than 4ft doesn’t bear thinking about.

If you’re handling a croc under 4ft you can throw a towel over their head to stop them from seeing you approaching. Then you grab it behind the head and hang on for dear life. It’s not too bad grabbing small crocs, compared to a similar-sized monitor that can scratch or tail-whip you.

Anything over 5ft is a similar process, but you will need two people. One must somehow attach a rope to pull the croc out of the water. It will thrash and spin, but that’s fine as long as there’s nothing nearby they can hurt themselves on. Once they’ve tired themselves out the other person jumps on. It’s the same process, throwing a towel over the croc’s eyes and then quickly jumping on to hold it. It can look quite crazy and disorganised, but it’s the best way. Crocs get tired out quickly from the buildup of lactic acid. Any croc measuring 6ft or so it will need two people to jump on. Crocs that big are strong enough to throw off the weight of just one person.

Bigger animals can’t be held by people. The risks are too great in most circumstances, so we use a couple of different methods for the sake of safety. The first involves training. By using small pieces of food as a reward (often a mouse is sufficient) crocs can be persuaded to enter a transportation crate. Training needs to occur regularly to get consistent results and be ready as an option when the process is necessary. We train 5 – 10 minute sessions at least four times per week, and if we don’t get the desired behaviour, the animal does not get the food. Of course, you need to have the training in place well before the need to move them arises.

Another way, if your croc is not crate trained, is to use a large, porous agricultural pipe, and you’ll need a few people on hand to do it. First, you’ll need to empty most of the water from the animal’s enclosure. Then, slide the big pipe until it is almost touching the tip of the croc’s jaws. Then someone must, very gently, lift the jaw using a long wooden pole, so that the pipe can slide underneath. Once the entire head is in the mouth of the pipe, another person can gently poke the croc’s tail, which will cause them to lurch forward into the tube. A few more nudges and you’ll have a tube full of croc and it’s time to seal up the end. Because the tubes have holes in, any water will run out when you lift it up. We recently used this method with our 160kg tomistoma when we were moving it from one side of the Zoo to the other, and it worked like a charm.

Up close with crocodiles

A little known croc fact

Most people think crocs are ancient animals that were around at the time of the dinosaurs, but that’s obviously not true. Far from being primitive, they have the most complex heart structure in the animal kingdom. They can actively control some of the valves in each of the four chambers of their heart – a talent no other vertebrate species can achieve. They do this to regulate the flow of blood and oxygen around their bodies, giving them the ability to remain submerged for extended periods. By using their heart and lungs in the same way we might use a scuba tank, crocs can open and close valves to let only small amounts of blood and oxygen flow – just enough to maintain adequate circulation. Using this method, a saltwater croc in Australia once stayed submerged for almost seven hours. Scientists still don’t fully understand how the crocodilian heart works.

The future for crocodiles

Crocodiles around the world are having a tough time, and it’s not easy to convince the general public that they deserve protecting. Not only are crocodiles less cute than may other endangered animals, they’re also considered deadly and dangerous – not qualities which endear people to cherish or protect them.

The biggest issues facing endangered crocodiles are environmental, as their habitats are being reduced and degraded by the sheer number of humans on the planet. Until a solution to the problem is found, zoos such as Crocs of the World are the last hope for these animals. Maintaining a captive collection of endangered species can act as a safety net, a kind of ark to keep the species alive should all of those in the wild become extinct. To find out more, and to help save these animals from extinction, visit Crocs of the World. I’m sure you’ll agree, even crocodiles deserve protecting.

www.crocodilesoftheworld.co.uk

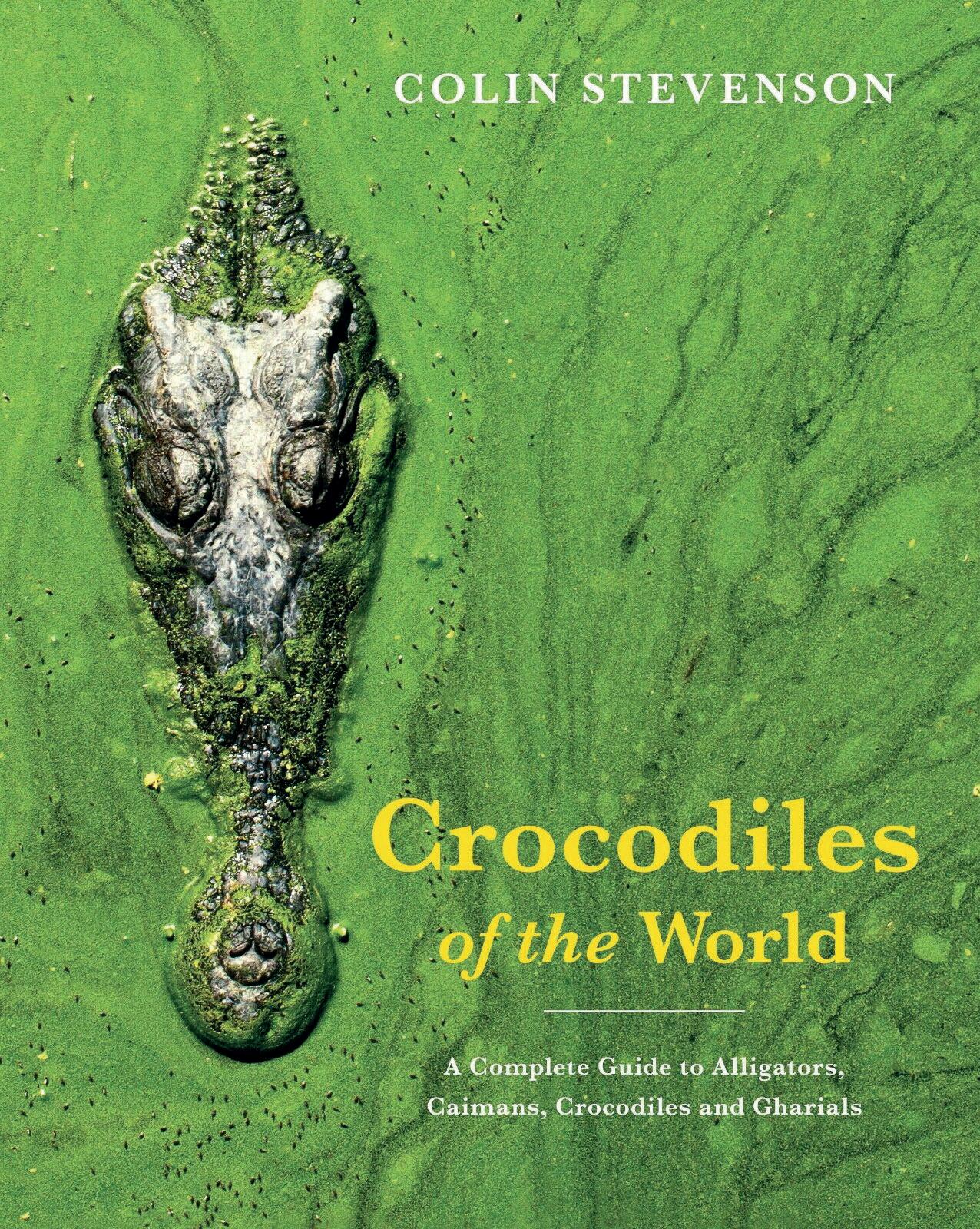

Colin Stevenson

Colin’s book, Crocodiles of the World, is a fascinating read. It covers the ecology and biology of crocs, detailing every species and the messy taxonomy in use today. It covers reproduction, habitat and conservation and, it has lots of pictures.

“I wrote the book because there’s not much information available about crocs which isn’t aimed at either children or scientists. I’ve tried to make the book interesting and accessible for everyone, but with enough detail and data to appeal to those with a specific interest.”

Colin Stevenson

Crocodiles Of The World

By Colin Stevenson

Publisher: Reed New Holland