Listening to a heartbeat is an intimate experience reserved for our closest relationships. The huts are designed as listening chambers. Multiple heartbeats play together in symphony corresponging to the number of chambers in the hut. h e a r t b e a t h u t s 01 project

Studies of masterworks. Drawings depict the tectonics

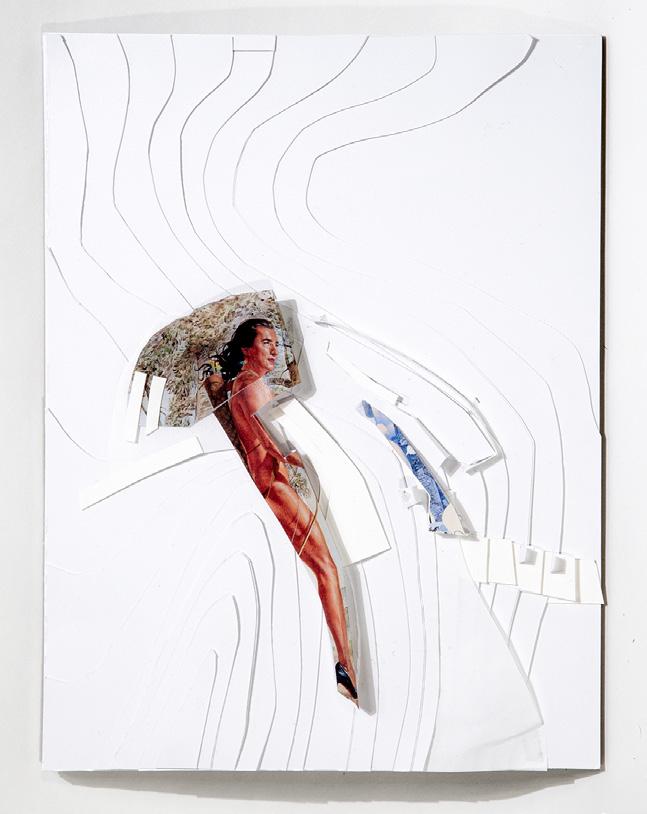

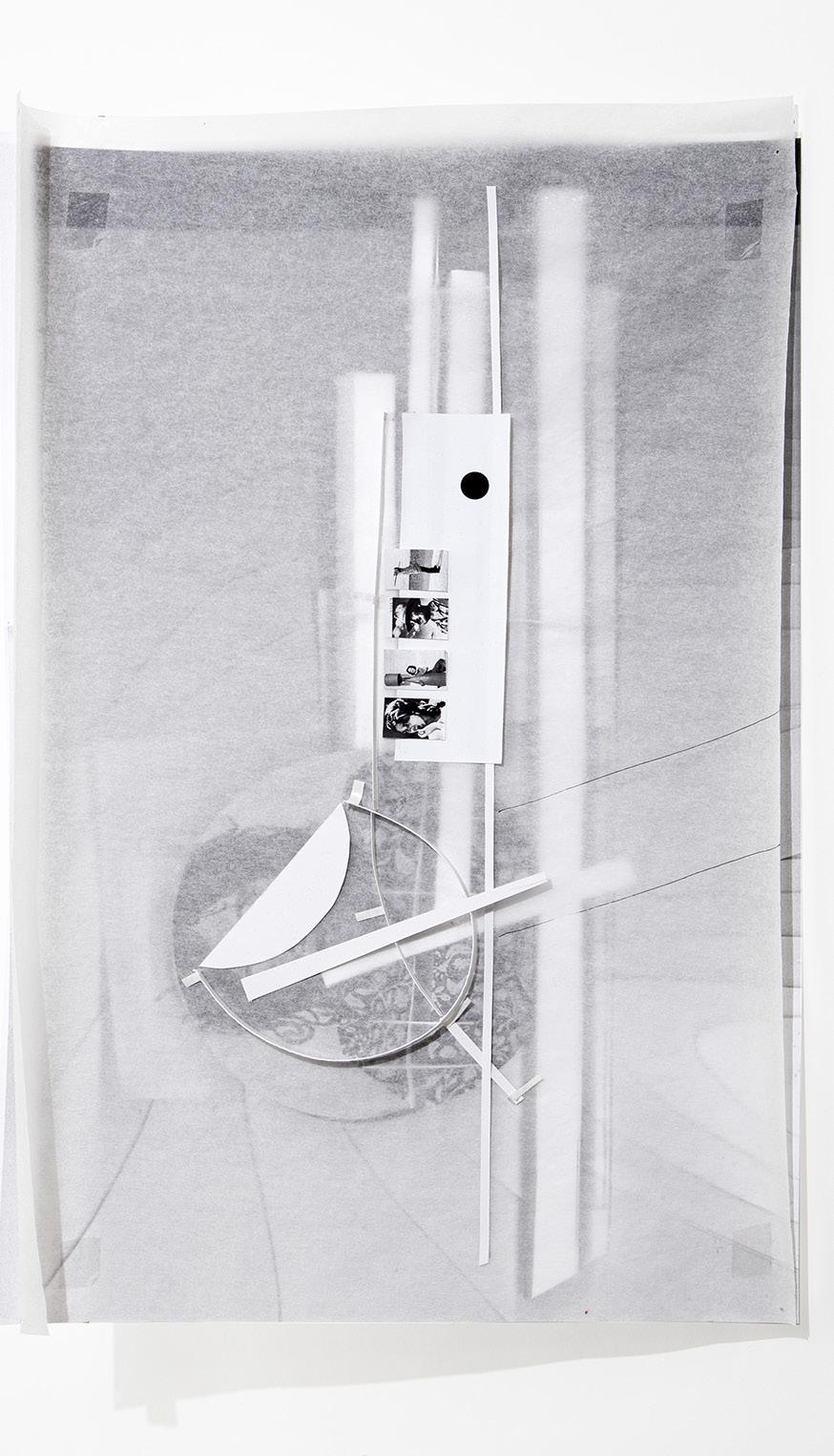

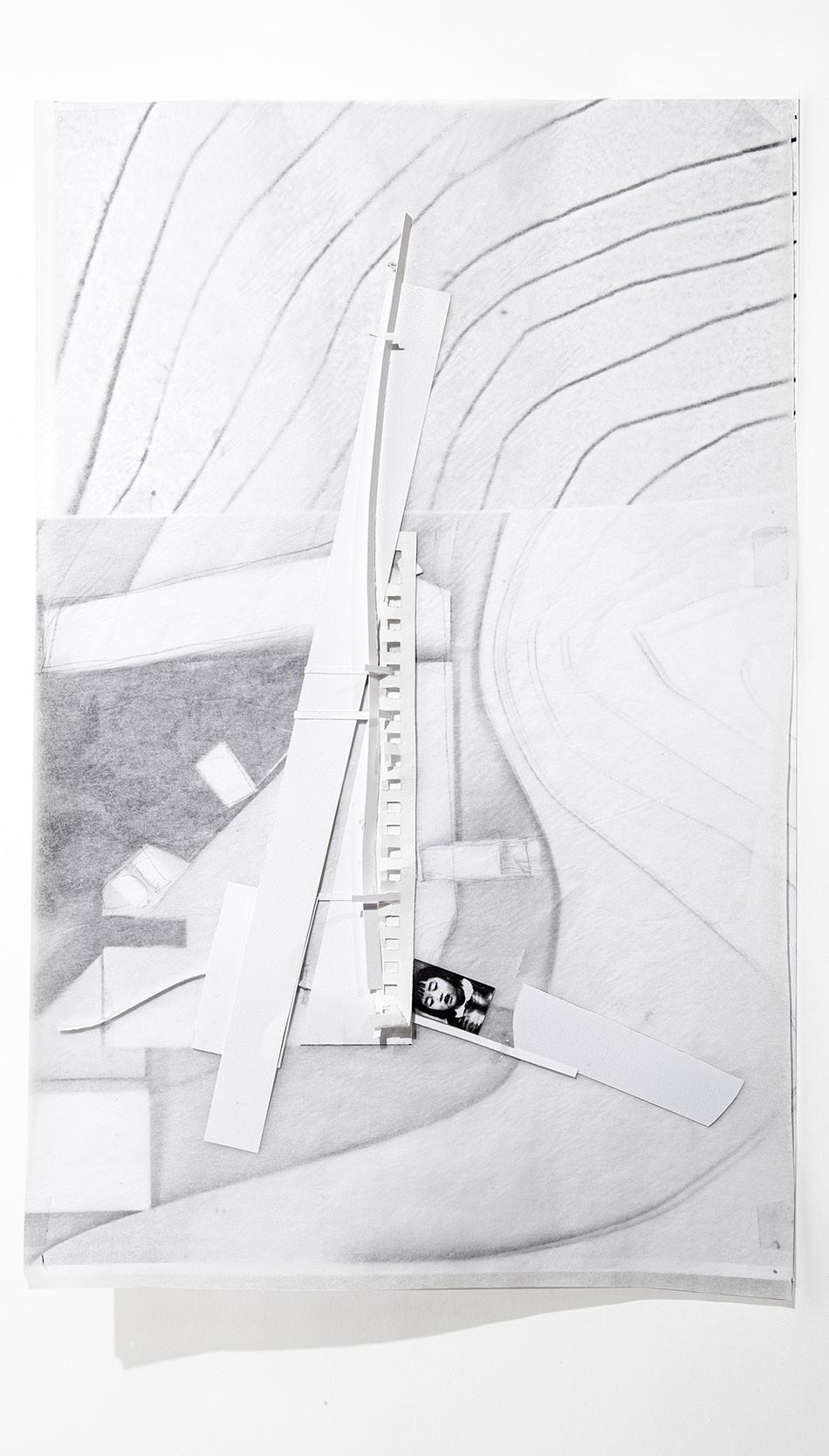

c h a r e t t e m o d e l s 03 project

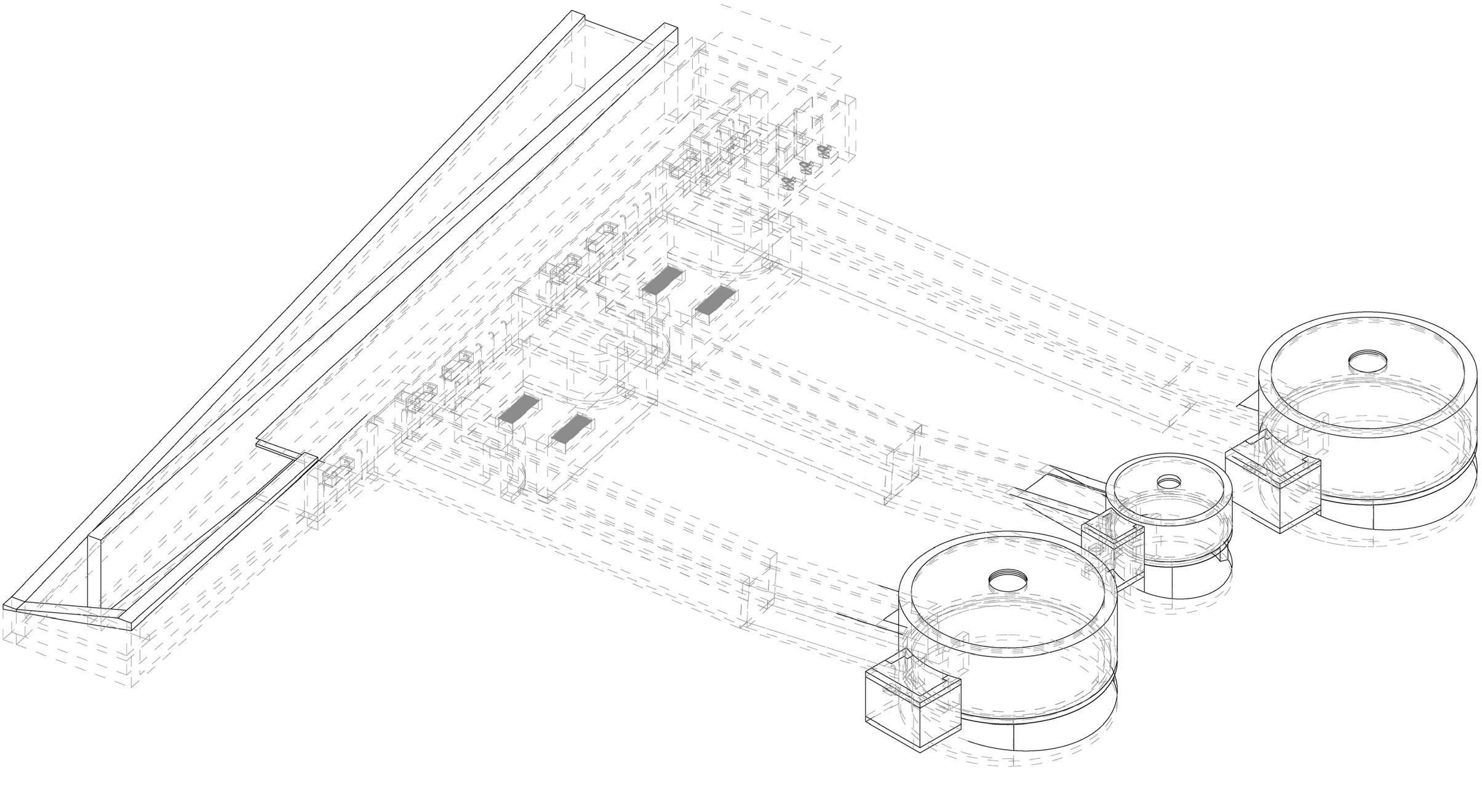

The model is an exercise using the tangent-plane method to discretize a doubly-curved surface into quadrilateral panels rather than using triangulation. The tension of the double-curvature is reflected in the gaps between panels as it is impossible to fully cover the surface using quadrilaterals. Using the gaps as an opportunity for columns turns this geometric tension into structural opportunity. (pictured left)

The building has no defined program. It is derived from two pre-determined sections as an exercise in resolving seemingly incompatible drawings. (pictured right)

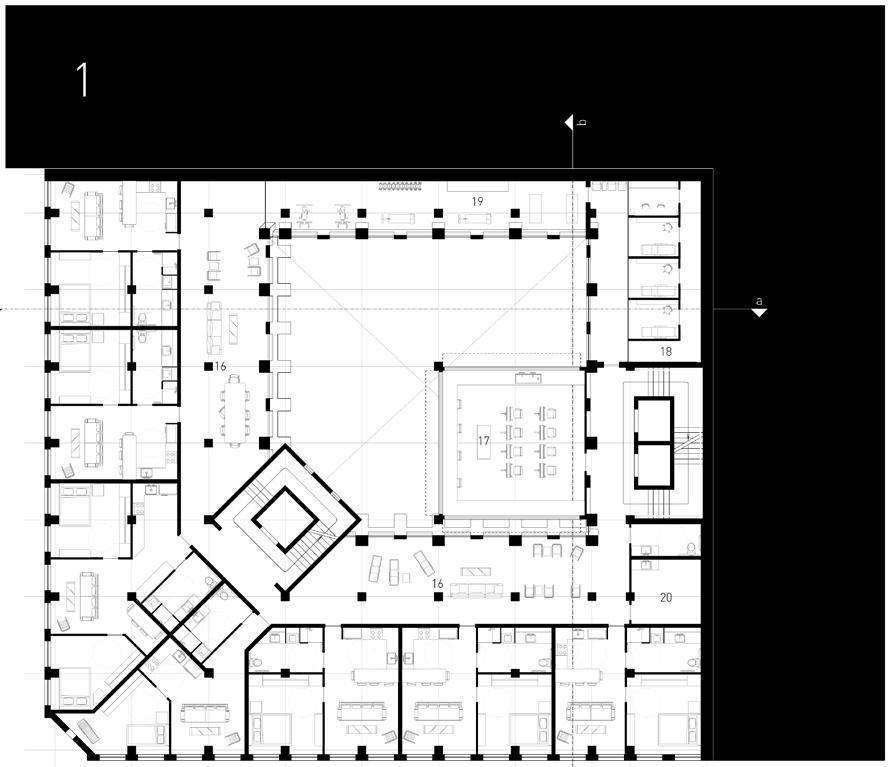

The programmatic requirements included 20 individual units, 10 shared units, communal dining, medical offices, garden spaces, a large multi-purpose space, a gym, and a full-serive kitchen. The model of the monastery promises a self-sustaining world of individual and collective dignity. As the inhabitants gently lean with age, the building leans to allow light; as we might hold the hands of our grandparents, the fingers of the cloisters wrap around the courtyard.

C4-7,15-37 / Parking Plan

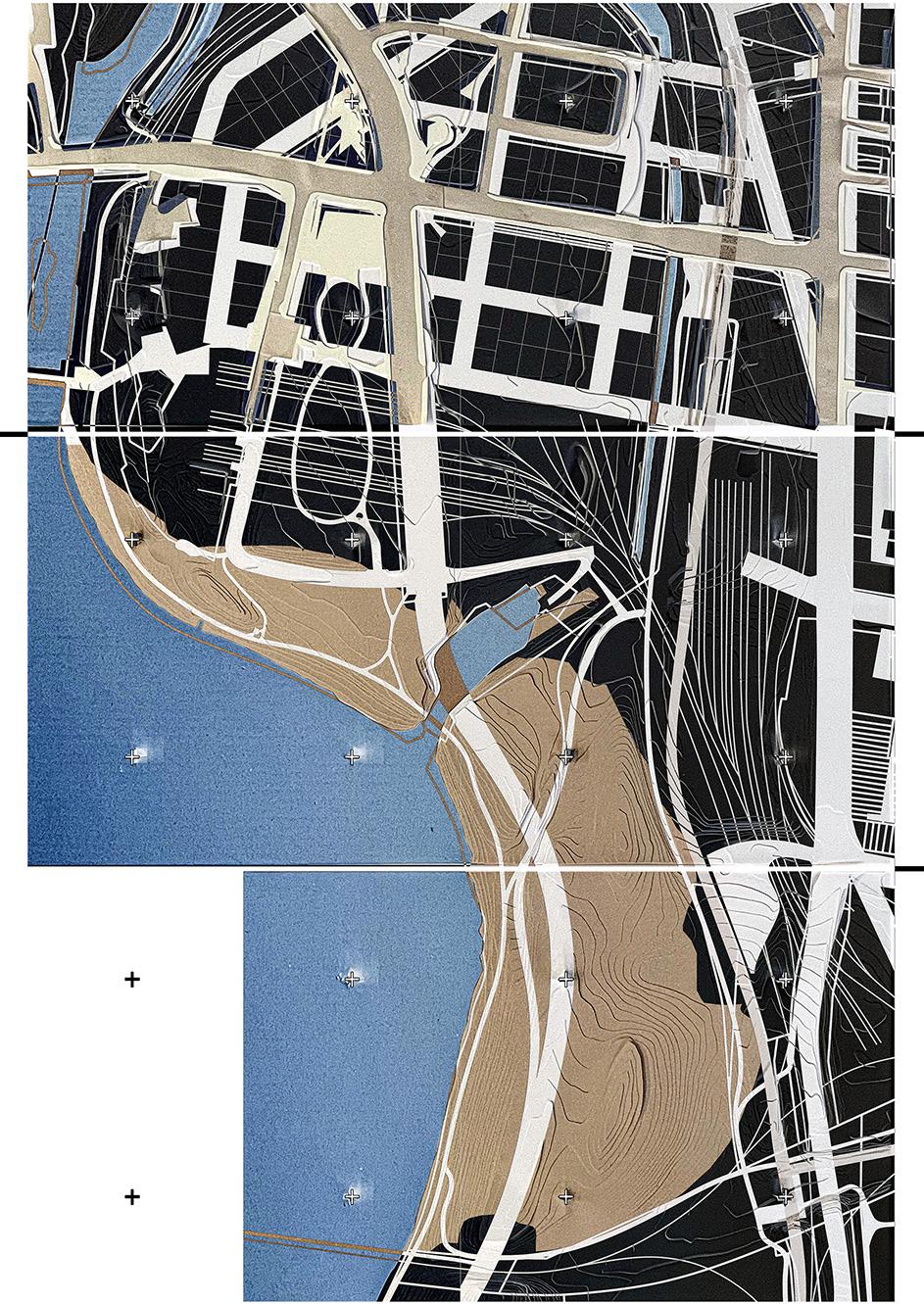

m a p p i n g 07

The Lachine Canal is a public waterway that once served the surrounding community in an industrial and recreational capacity. The current day pollutant levels prevent the waterway from being safely used for swimming. Private condo pools now act as a proxy. (pictured left)

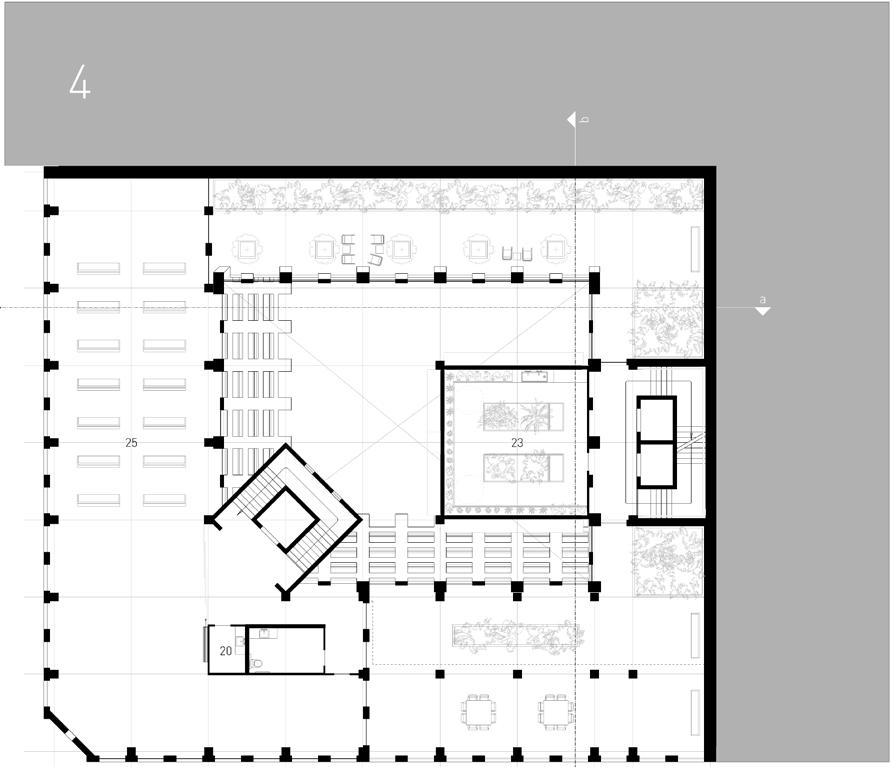

Burial patterns of the Bedouin have been shifting with the transition from nomadic to permanent settlements and the territorial claims of local government. Bedouin are less likely to be buried in a single grave where they die. Rather than spread throughout the Negev/Naqab, the Bedouin dead are now concentrated in defined cemeteries. The idea of erasure and return to the desert is now at odds with the need for proof of ancestry as a territorial claim. (pictured right)

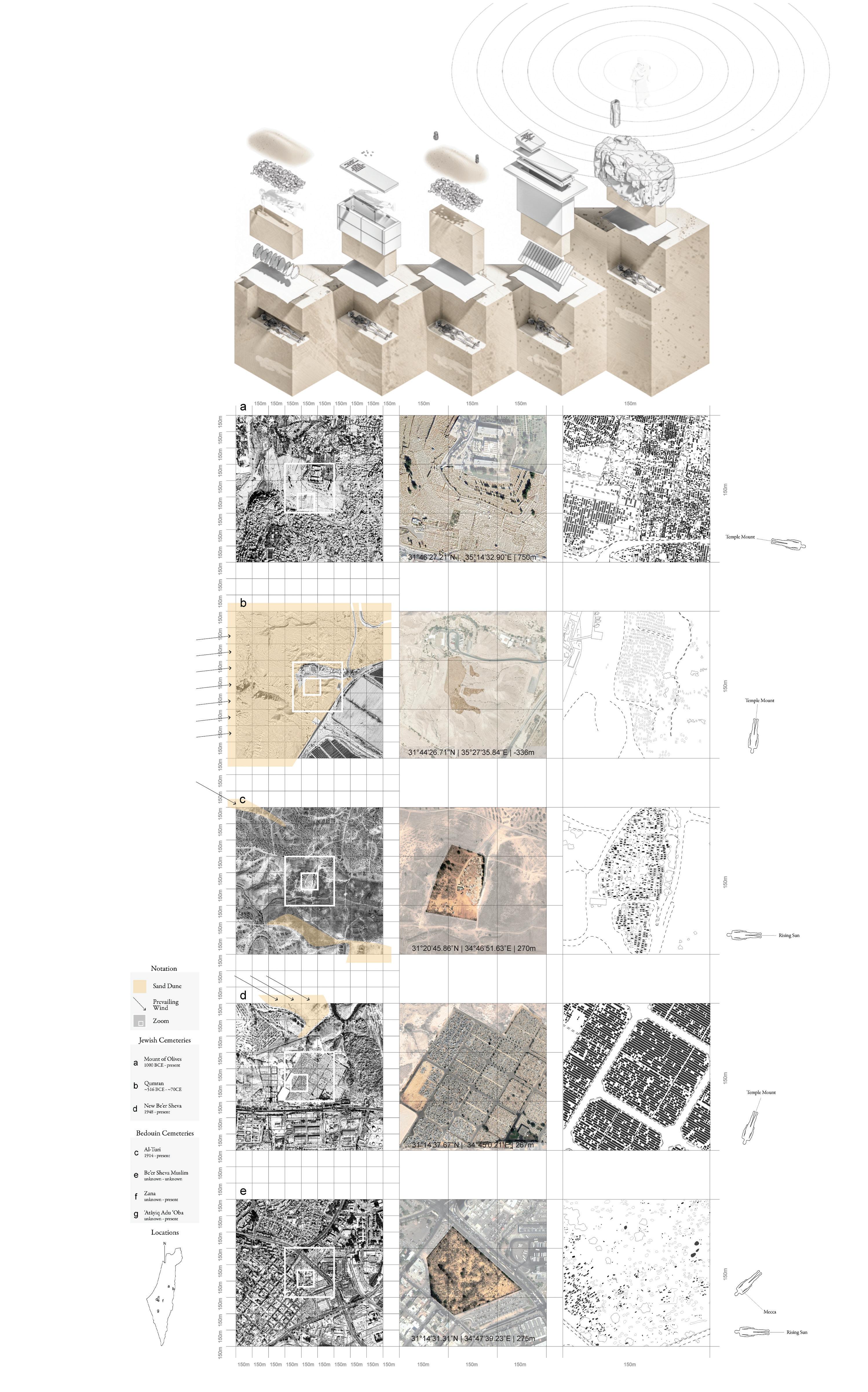

Two undressed tombstones known as Ansâb mark the head and foot of Bedouin graves. In effort to prevent ongoing classification of burial grounds as no more than “several piles of stones” and developement of the land, we propose an unignorable series of Ansâb that mark the East-West and Southwest-Northeast axes of cemeteries in the Negev/Naqab. These axes are in line with the direction of burial and rebirth in traditional and formal Islamic Bedouin belief. (pictured left)

Traditional Bedouin burial involves erasure over time as sand blankets simple stone graves. Saints of Bedouin tribes would be buried atop ridges so that their spirits might watch over their territory until the time of resurrection. In order to maintain the sanctity of Bedouin graves in the face of infrastructural development, we propose mounds of gabion that fortify cemeteries and house the remains of revered ancestors so they might watch over their kin. (pictured right)

In order to maintain the sanctity of burials now and in the future, bodies of Jews, Bedouin, Muslims, and Christians are buried alongside one another in a multifaith necropolis. A funerary structure buried beneath the hill acts as the threshold between living and dead. As one moves into the earth, the path turns with the East - West axis, aligning with all three abrahamic entry sequence conventions. Inside, a communal ritual washing area can be found where benches are provided for muslim visitors and cups for jewish visitors. Preparations of the deceased take place behind the washing wall. After washing, the dead and the living descend deeper into the earth before rising again into the main prayer chamber. Sinuous burial plots grow out of the prayer chambers and weave along the topography where the deceased of diverse cultures share common ground.

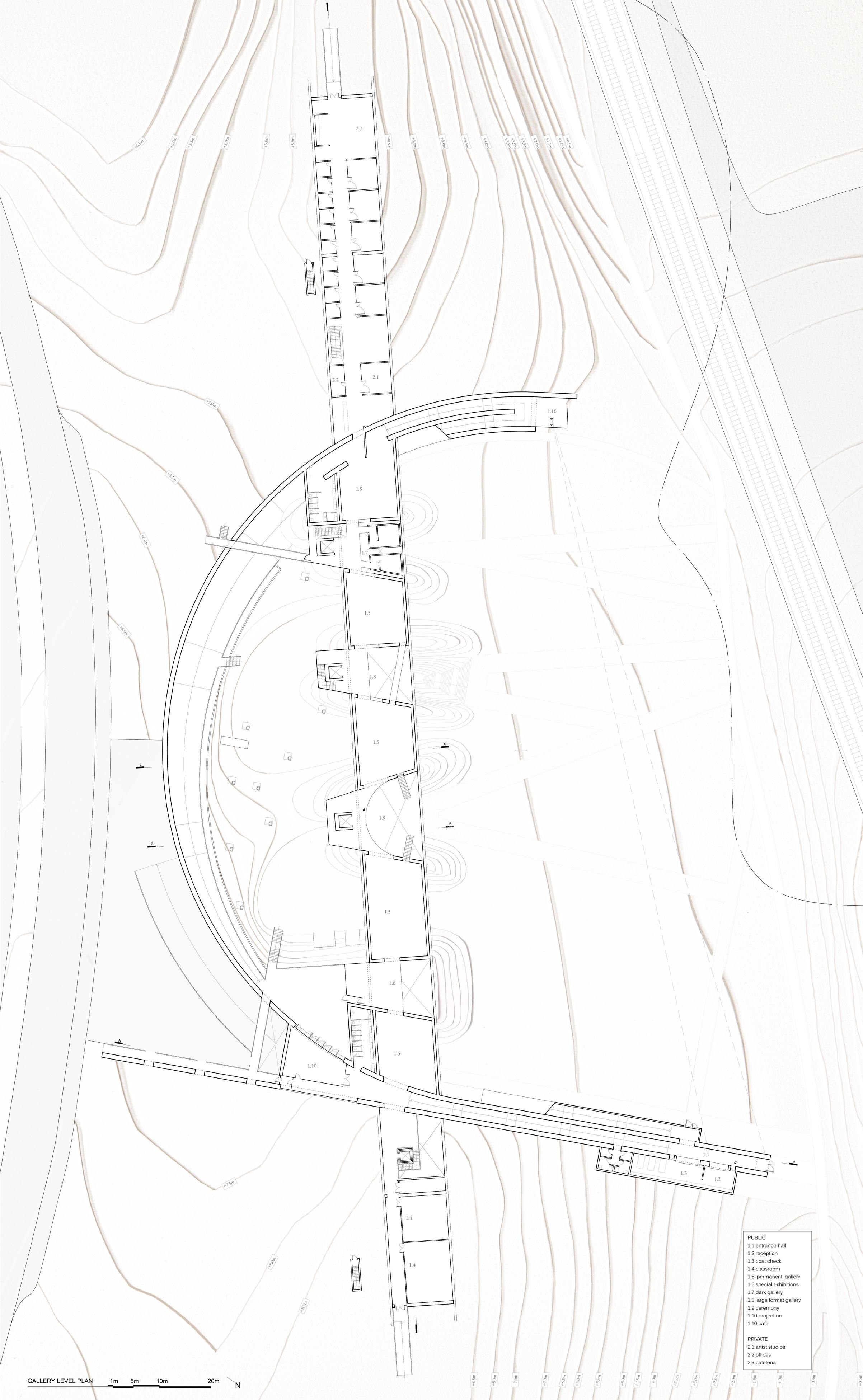

p o r t r a i t g a l l e r y 11 project

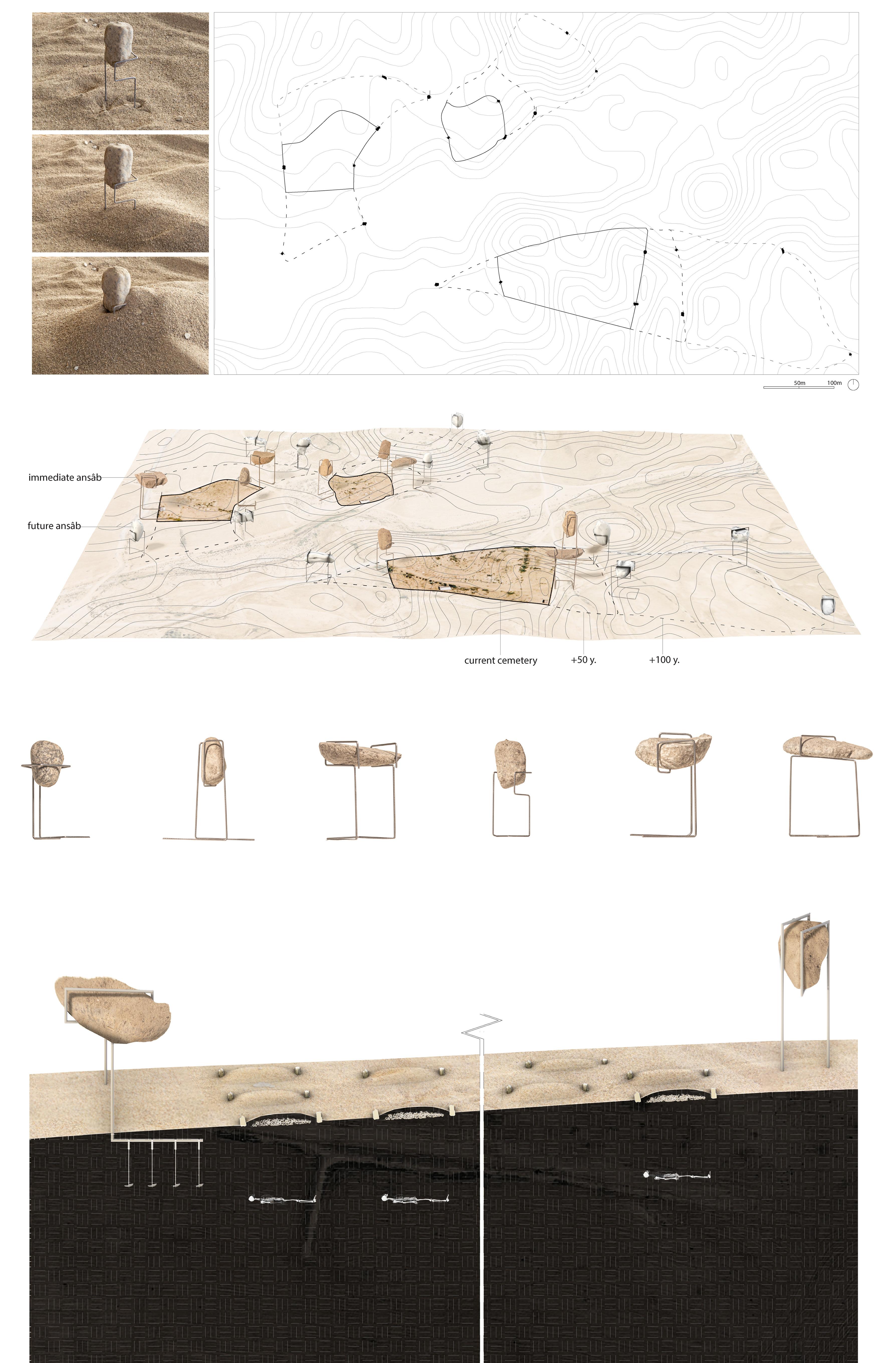

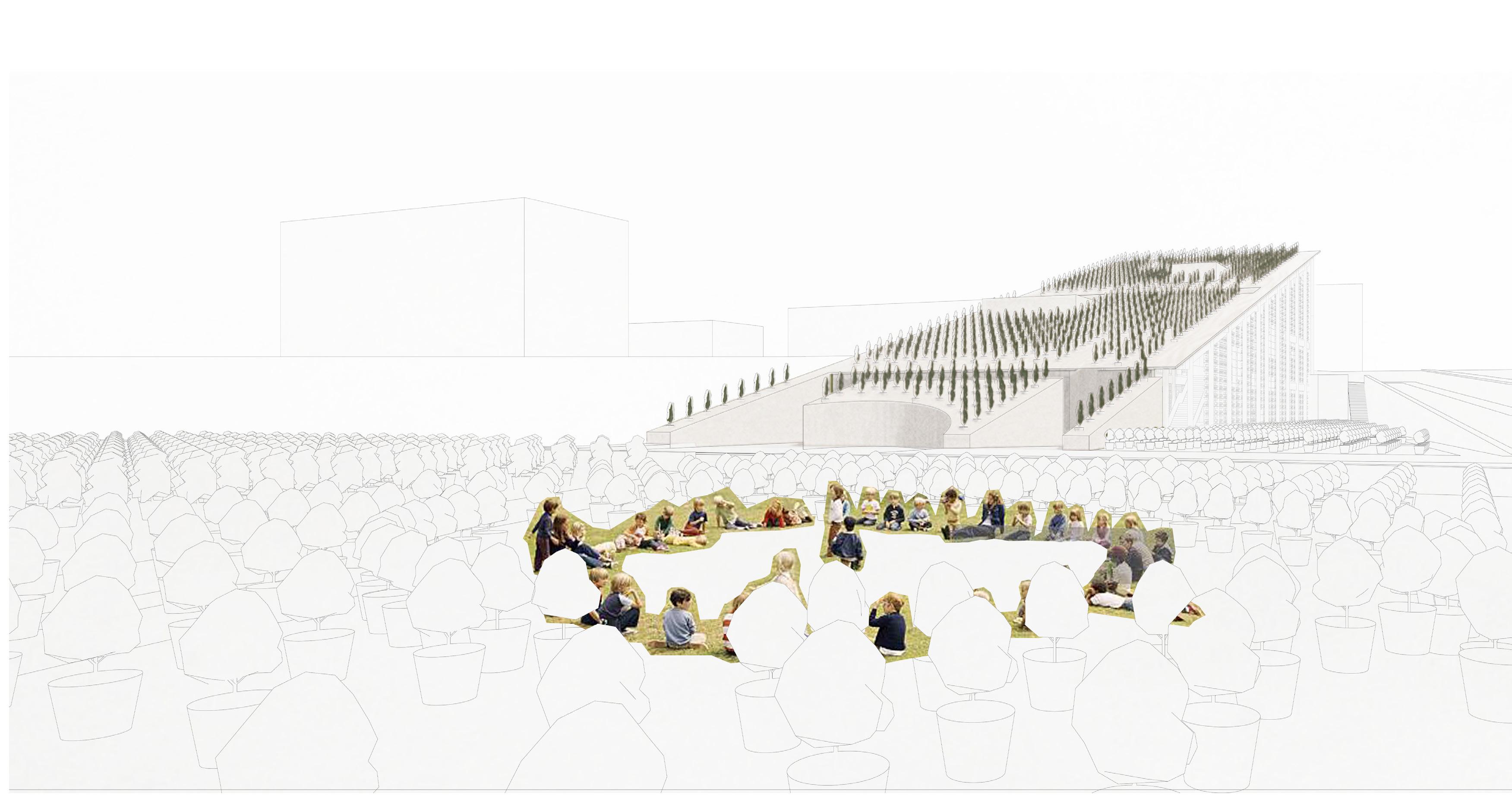

Since 1939 the Portrait Gallery of Canada has faced a series of successive failures to establish itself as a national institution. This thesis aims to explore the potential for such an institution while staging a series of questions on and critiques of land-use, museum types, institutional architecture, and narratives of Canadian national identity. The proposal sits in distinction to current plans by the National Capital Commission for privatization of publicly held lands on LeBreton Flats in Ottawa. As a public institution and resolution to a long history of mismanaged land and unrealized potential for a major national museum, the proposed Portrait Gallery of Canada will act as a repository for the identity of individual and collective Canadians across time-and in time.

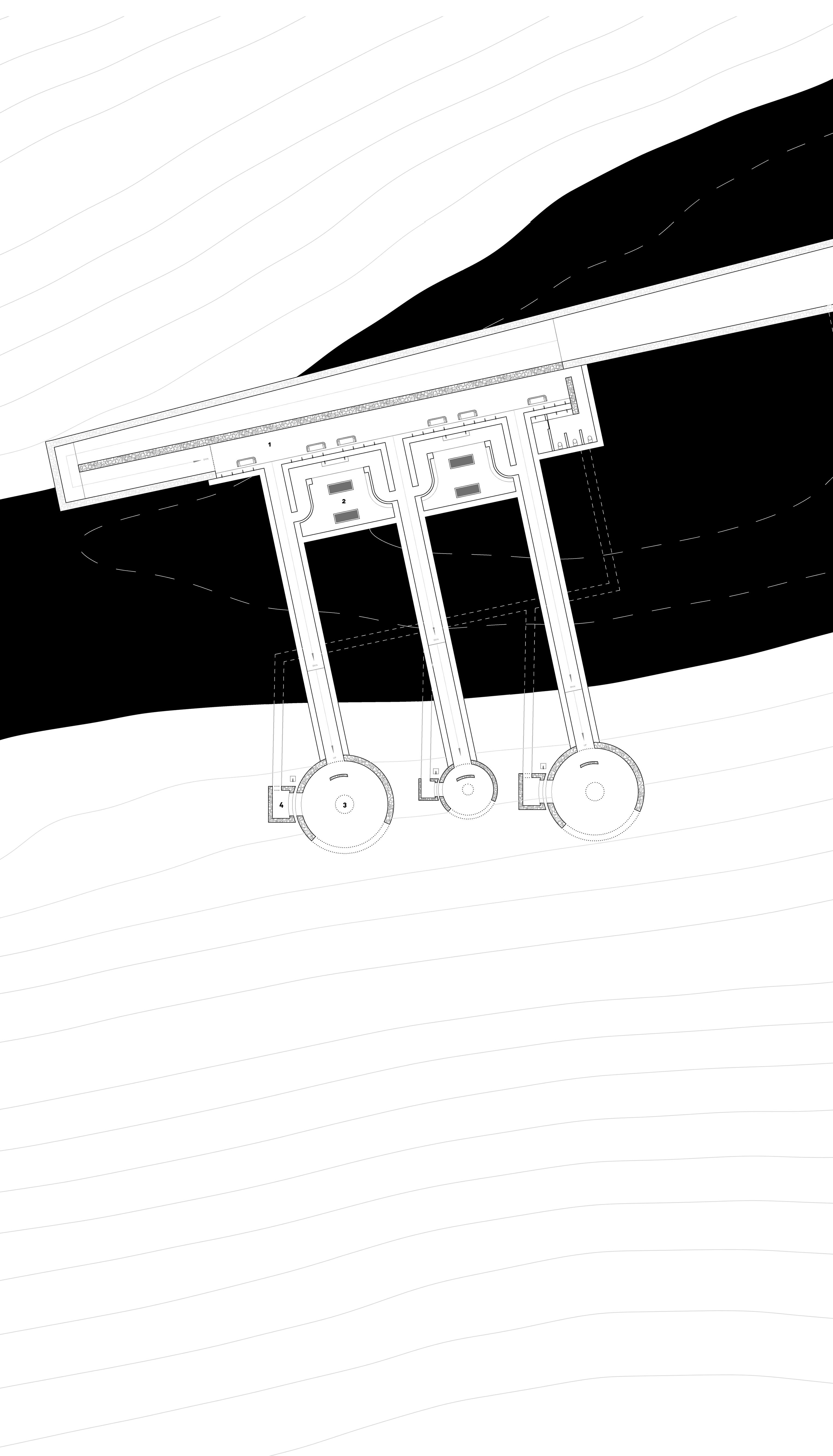

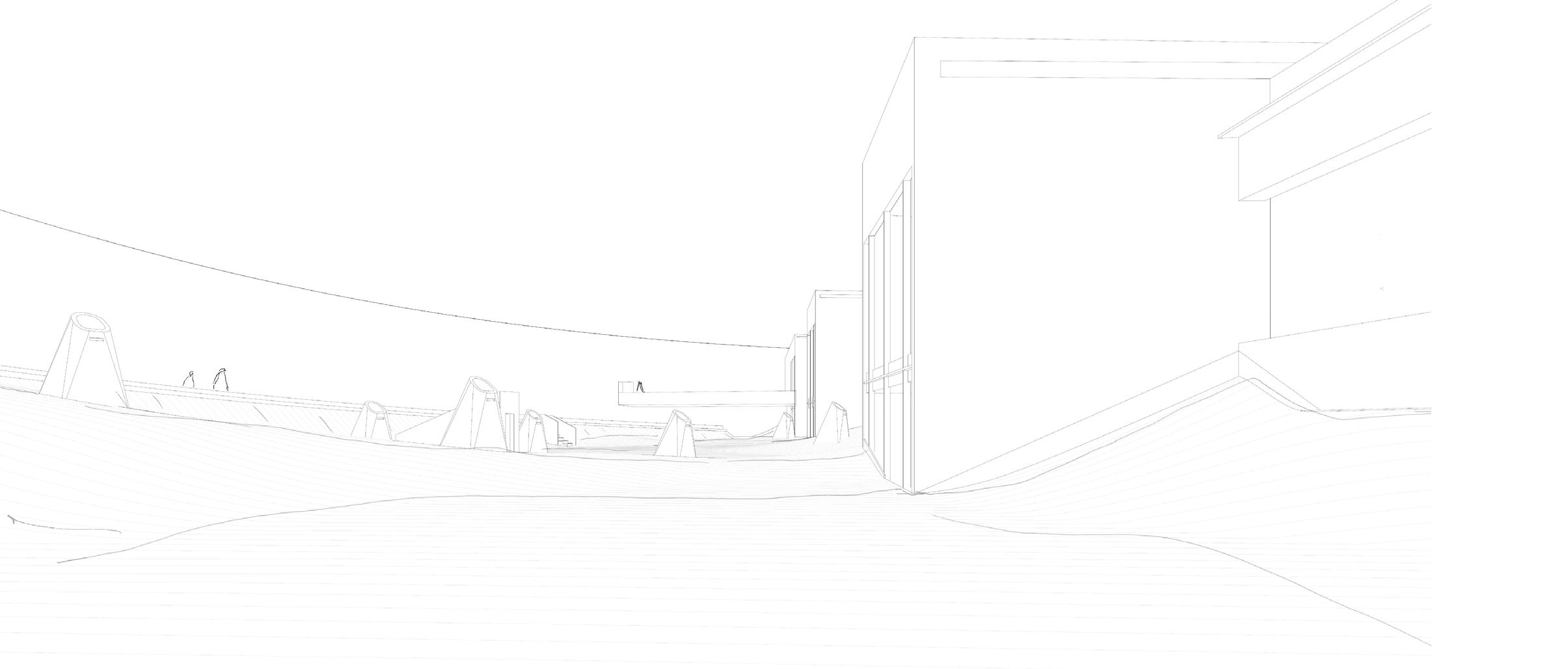

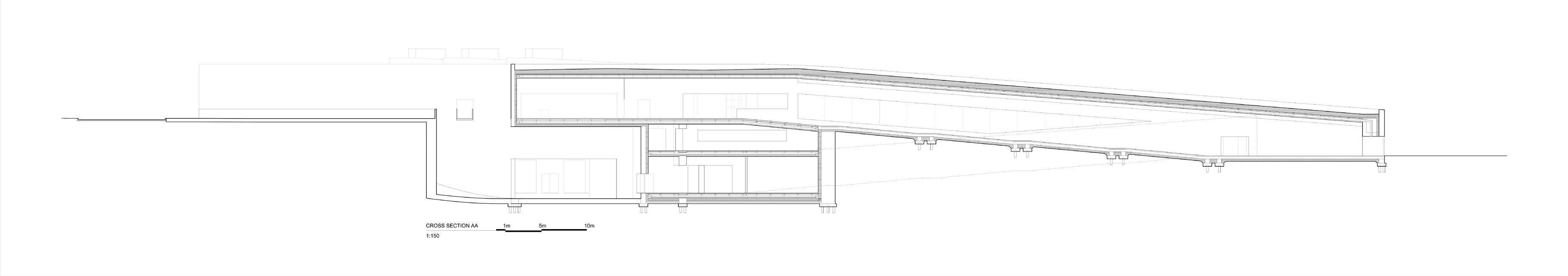

As visitors walk east around the crest of a tree covered hill, they are met with a retaining wall carving an arc around the valley, constituting a new public bay where Nepean Bay once was. A single storey gallery supported by two parallel horizontal timber beams 2 meters above grade bridges the bay; it rests upon the crests of small hills within the bay and on two pre-existing hills beyond the arc. The large hills on either side of the bay are the topographic result of the 1964 municipal landfill. Trees atop these hills are the tallest forms in the landscape. The smaller hills within the bay are constructed landscape, enveloping concrete piers. Points of contact between the gallery and the earth mark entries to communal atria which can be accessed without rising to the level of the galleries. The lifted gallery acts as an elevated threshold, allowing visitors to pass underneath toward large open-air forums contained behind.

Gallery Level - Reception, coat check, and information services are all contained within the volume of the western primary entrance ramp. When visitors reach the gallery level, they are met with a 235-meter-long volume intersecting their path of travel. Galleries and communal spaces are contained within the bounds of the arc, with classrooms and offices located in the sections of the building extending beyond. Thick concrete walls define the rhythm of the curated zones, alternating between three-storey vertical connection to the subterranean archive and elevated gallery. An unbroken line of sight extends the full length of the galleries, placing each portrait in spatial relief, conceptually linking varied displays of Canadian identity and culture without giving any specific exhibit preferential placement.

Ground Level - Communal atria are the spatial and conceptual connective tissue between the archive and the galleries. They are open to all for use and perhaps hold the greatest potential for defining national identity. By allowing gathering spaces to become fundamental to the rhythm of the gallery sequence, formal exhibits and their inherent cultural authority are made equal with the day-to-day happenings of Canadians utilizing the spaces.

Archive Level - Echoing the galleries above, the archive maintains a visual continuity across the bay. The archive both receives images and testaments by the visitors as well as displays them alongside more standard forms of exhibited portraiture. Beyond the bounds of the arcing retaining wall is the special event space and lecture hall to the west and the library to the east. To the north, between the arcing wall and linear open archive is the back of house. Visible through glazed walls of the open archive, these spaces are sequential programs of receiving, curatorial workspaces, exhibition preparation, and closed archival storage; a choreography of receiving representations of Canadian identity made visible to spectators.

t: (438) 927-9705

e: evan_kettler@hotmail.com