13 minute read

including vaccination and wildlife issues

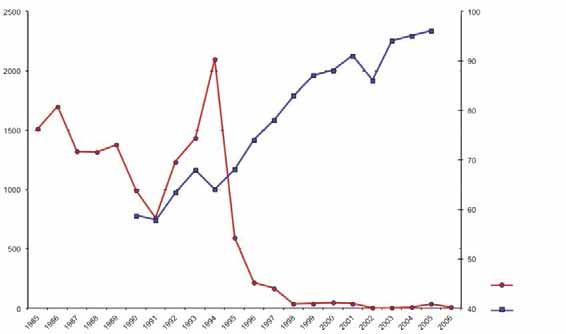

No. of outbreaks % vaccination (heads)

Fig. 4 Evolution of the foot and mouth disease outbreaks and vaccination coverage in Brazil

Advertisement

Source: PANAFTOSA/PAHO/WHO Number of outbreaks

% vaccination

The quality of the immunisation achieved is checked by post-vaccination evaluations based on the farmer’s compulsory self-declaration and on post-vaccination immunity studies (PVMs) carried out by the national programmes to ascertain the levels of herd immunity.

Surveillance and prevention

Transparency has been an important element for decision-making among the countries in the process of controlling and eradicating FMD. The Veterinary Services in every American country count with a national animal disease surveillance system forwarding weekly and emergency information on the occurrence of vesicular diseases to the Continental Epidemiological Information and Surveillance System (SIVCONT), coordinated by PANAFTOSA/ PAHO/WHO. SIVCONT was created in 1973 and today collects information on vesicular syndromes, nervous syndrome in herbivores, respiratory/neurological syndromes in birds and haemorrhagic syndrome in swine. The system manages an Internet database on a number of diseases according to the species and disease syndromes mentioned. It is structured to allow early notification and information sharing from the suspicion down to the final diagnosis. The information is channelled through 6,483 official field units, manned by more than 18,000 employees, by official diagnostic laboratories and also the two OIE Reference Laboratories on FMD in the region, providing elements for the development of eradication strategies. During 2011, SIVCONT registered 783 suspicions, of which only eight, across three countries, were confirmed as FMD. There were 769 outbreaks of vesicular-like diseases confirmed by the laboratory network, and six samples were negative. As regards the role played by wild species in the maintenance of FMD infection, it is widely accepted that several studies have revealed that bovine cattle are the only reservoir of the FMDV in South America. Although the bovine population used to be important in terms of numbers (southern Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay), its role in the maintenance of infection was always secondary. Moreover, there is no evidence of transmission of the disease between domestic animals and wildlife, even in those areas without vaccination. Foot and mouth disease has recurred a few times in the disease-free countries/zones since the continent achieved a higher sanitary status early in the 2000s, and on most of those occasions it was possible to trace back the origin of the disease. The Veterinary Services have reacted immediately to the emergency with contingency plans and well-organised and trained emergency workforces. These teams were responsible for tracing back cases and identifying their sources, bringing additional expertise to the surveillance schemes already in place. This led

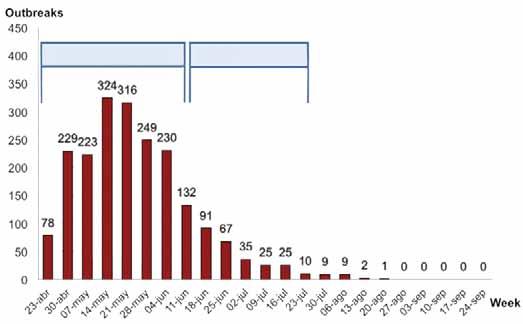

to successful containment operations, when reintroductions threatened free zones and countries. Nonetheless, the emergencies reinforced the need for transparency and well-trained emergency teams. Figure 5 provides the case of Uruguay in 2001 as an example of effective control of an extensive epidemic affecting non-immune populations using the combination of mass vaccination, movement restriction and disinfection.

Outreaks per week

Mass vaccination Mass revaccination

Outreaks by month

April 97 May 1,277 June 563 July 102 August 18 September 0 October 0 November 0 December 0 Total 2,057

Fig. 5 Control of foot and mouth disease epidemic in Uruguay, 2001, through movement restrictions, disinfection and mass vaccination

Source: Ministerio de Ganadería, Agricultura y Pesca, República Oriental del Uruguay

Public–private partnerships

The Hemispheric Program for the Eradication of Foot-and-Mouth Disease strategy relies on regional and subregional plans based on political commitment, coordination and collaboration between the national Veterinary Services towards concerted actions. Furthermore, it is innovative on proposing public–private partnerships with livestock associations and the active participation of local communities. The modality of public–private partnerships, though, depends on the idiosyncrasies and regulatory framework of each country. The experiences were fully developed in Argentina, where 310 local entities were operative in 2011, as well as in Colombia where a farmer’s association manages approximately 90 local committees. To a lesser extent, the experience was also successful in other countries, reaching higher levels of vaccination and a proactive response from the livestock sector during emergencies. This cooperative scheme has proven positive when the financing of the national programmes is analysed. There was a positive trend in the investments made by both governments and livestock sector in the last six years. According to data provided by the countries to the South American Commission for the Fight Against Foot-andMouth Disease (COSALFA), the investments made in 2011 totalled US$1.3 billion, which meant a 13% increase in the investment when compared with the previous year. Nevertheless, it is expected that a sizeable increase in the investment will be needed to confront the challenges of eradicating the disease from the continent. According to the PHEFA budget for the period 2011–2020, on top of the resources needed to maintain the national programmes and the cost of vaccination, approximately US$18 million shall be invested in technical cooperation.

Conclusions

At the beginning of 2012, the countries in South America showed a positive situation, as can be seen from Table I and Figure 6 Two hundred and eighty-five million bovines (85% of the total population) in more than 3.5 million herds (70%) in 71% of the geographic area in South America are free from FMD, either with or without vaccination.

Table I Foot and mouth disease sanitary situation in South America, 2012

Sanitary situations

Km2 Surface Cattle and buffalo herds

Total cattle and buffalo heads

% No % No %

Free without vaccination 3,808,129 21.40 854,912 16.9 11,694,110 3.5

Free with vaccination 8,743,526 49.20 2,662,945 52.7 272,851,766 81.5

Buffer zone 88,190 0.50 16,869 0.3 479,199 0.1

Not free 5,124,056 28.80 1,522,726 30.1 49,557,982 14.8

Total 17,763,901 100.0 5,057,452 100.0 334,583,057 100.0

Total free 12,639,845 71.20 3,534,726 69.9 285,025,075 85.2

Source: PANAFTOSA/PAHO/WHO

The aim of the PHEFA 2020 is to eradicate disease. FMD still exists in some endemic countries, which represents a threat to those countries/zones already recognised as free of FMD. This geographically restricted endemism led to the development of multinational initiatives, whose final goal is to raise the average FMD status in order to establish a safer collective environment. Regional coordination and country-to-country collaboration is needed if FMD is to be swept out of the continent.

Free zone without vaccination Free zone with vaccination Not free Protection zone Suspended status

Fig. 6 Foot and mouth disease situation according to World Organisation for Animal Health status in South America, 2012

Source: PANAFTOSA/PAHO/WHO

South America has a vast experience of FMD control and eradication, which should be considered, and regional solutions could be used as a model by other regions where the disease is still endemic. A FMD-free continent by 2020 is a reachable objective, but it will depend more than ever on the continuing political commitment of governments, regional coordination efforts and support of the livestock sector.

Further reading

Correa Melo E. & López A. (2002). – Control of foot and mouth disease: the experience of the Americas. In Foot and mouth disease: facing the new dilemmas (G.R. Thomson, ed.). Rev. Sci. Tech. Off. Int. Epiz., 21 (3), 695–698. Correa Melo E. & Saraiva V. (2003). – How to promote joint participation of the public and private sectors in the organization of animal health programs. In Veterinary Services: organisation, quality assurance, evaluation (C.I. Lasmézas & D.B. Adams). Rev. Sci. Tech. Off. Int. Epiz., 22 (2), 517–522. Mendes da Silva A.J., Brasil E., Saraiva V., Darsie G. & Naranjo J. (2011). – SIVCONT epidemiological information and surveillance system. Challenges of animal health information systems and surveillance for animal diseases and zoonoses. In FAO Animal Production and Health Proceedings, 14, 57–62. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome. Available at: bvs1.panaftosa.org.br/local/File/textoc/MendesSilva-SIVCONT-FAO2011.pdf. Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) (1988). – Plan of Action: Hemispheric Foot-and-Mouth Disease Eradication Program in South America. In Proceedings of the Meeting of the Hemispheric Committee on Foot-and-Mouth Disease Eradication, Washington, United States of America, 6–7 June, 32 pp. Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) (2011). – Plan of Action: 2011–2020 Hemispheric Foot-and-Mouth Disease Eradication Program in South America. In Reunión del Comité Hemisférico para la Erradicación de la Fiebre Aftosa – COHEFA 12. Available at: ww2.panaftosa.org.br/cohefa12/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=80&Itemid=9 7&lang=es. Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) (2011). – Situación de los programas de erradicación de la fiebre aftosa en América del Sur. 39ª. Reunión de la Comisión Sudamericana para la Erradicación de la Fiebre Aftosa-COSALFA, Asunción, Paraguay. Rweyemamu M., Roeder P., Mackay D., Sumption K., Brownlie J., Leforban Y., Valarcher J.F., Knowles N.J. & Saraiva V. (2008). – Epidemiological patterns of foot-and-mouth disease worldwide. Transbound. Emerg. Dis., 55 (1), 57–72. Saraiva V. (2003). – Vaccines and Foot-and-Mouth Disease Eradication in South America. In Vaccines for OIE List A and Emerging Animal Diseases (F. Brown & J. Roth, eds). Dev. Biol. (Basel), 114, 67–77. Saraiva V. & Darsie G. (2010). – The use of vaccines in South American Foot-and-Mouth Disease Eradication Programs. The International FMD Symposium and Workshop, Melbourne, Australia. Sutmoller P., Barteling S., Olascoaga R. & Sumption K. (2003). – Control and eradication of foot-and-mouth disease. Virus Res., 91, 101–144.

Maintaining foot and mouth disease-free status: the southern African experience (including vaccination and wildlife issues)

M. Letshwenyo

Ministry of Agriculture, Private Bag 003, Gaborone, Botswana Correspondence: m.letshwenyo@oie.int

Summary

Agriculture is very important to the economy of most southern African countries, where it provides food, raw materials, income and employment. The Southern African Development Community has realised the strategic role played by this sector in the economies of its Member States, and has within its structures a strong agriculture representation. Livestock generally dominates the agriculture contribution; key to this is access of livestock and their products to markets. This requires freedom from diseases of economic importance such as foot and mouth disease (FMD). FMD is primarily a disease of cloven-hoofed animals. There are seven serotypes, but in southern Africa the predominant serotypes are the Southern African Territories (SAT) 1, 2 and 3. Cattle are particularly susceptible while small ruminants are rarely affected by the disease. Occasionally some cloven-hoofed wild antelopes are affected but the disease is considered only transient in these species. African buffalo (Syncerus caffer) is the reservoir host of the FMD virus, making eradication of FMD virtually impossible in southern Africa. Some countries have developed mechanisms of separating susceptible domestic animals from buffalo, using barriers and biosecurity measures to contain the virus. In addition to technical assistance from collaborating partners, countries were able to provide assurances on the safety of their products. Consequently, these countries have zones recognised by the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) as FMD free. This status has allowed the countries to successfully trade in livestock products both regionally and internationally. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to share the southern African experience in maintaining FMD-free status, with particular reference to Botswana.

Keywords

Foot and mouth disease – Southern Africa – Vaccination – Wildlife.

Introduction

Livestock production is very important to the economy of most countries in southern Africa, where it is the backbone of rural development, providing food, raw materials, income and employment. The region has about 64 million cattle, 39 million sheep, 38 million goats, 7 million pigs, many more other species, such as poultry, and a rich diversity of wildlife. An estimated 75% of livestock is kept under smallholder traditional systems in shared grazing areas (10). The contribution of livestock agriculture to the national gross domestic product is significant, but even more important is the socio-cultural contribution, which may not be easily quantified. Trade in livestock and their products are dependent on freedom from diseases of economic importance such as foot and mouth disease (FMD).

Foot and mouth disease is a highly infectious viral disease of cloven-hoofed animals caused by Aphthovirus. FMD was first described in southern Africa in the late 1700s and the 1800s; it disappeared in the region with the advent of the rinderpest pandemic in 1896, but reappeared in 1931 (3). There are seven types – O, A, C, Southern African Territories (SAT) 1, SAT 2 and SAT 3 and Asia 1 – all of which are immunologically distinct, and there is no

cross-protection between them. The subtypes continuously undergo antigenic drift; requiring regular improvements to FMD vaccines. In southern Africa, FMD is primarily caused by the viruses SAT 1, SAT 2 and SAT 3. Cattle are the most susceptible, while other domestic species are only occasionally affected and their role in the epidemiology of the disease is controversial (1, 4). African buffalo (Syncerus caffer) are known maintenance hosts of the FMD virus in the environment (2, 5, 6). Young buffalo calves between the age of six and eight months may occasionally develop clinical FMD; this has been attributed to the waning off of maternal antibody protection (13). Studies in the region indicate that the majority of buffalo herds are infected with FMD SAT viruses (7). Consequently, buffalo are confined in game reserves; the presence of buffalo in livestock areas is considered a disease threat and they are immediately returned to wildlife areas. The role of other wild ongulates in the epidemiology of FMD is not well understood; however, they are believed to be only transiently infected (3, 4).

Foot and mouth disease causes losses in export earnings, disease control and compensation costs, as well as socio-economic costs (10). Some countries in the region have for many years developed mechanisms of separating susceptible domestic animals from wildlife using both natural and artificial barriers, applied in conjunction with biosecurity measures between areas of different animal health status. This has effectively confined the FMD virus within the infected areas, while securing virus-free areas (3, 10). Consequently, they have attained an FMD-free zone or country where vaccination is not practised, as defined by the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE). These measures have made trade of animals and animal products possible from the FMD-free areas, and assisted the economies of these countries significantly (10).

The conventional methods of attaining FMD-free status is through zoning; according to Chapter 4.3 of the OIE Terrestrial Animal Health Code (Terrestrial Code) zoning is defined as a procedure implemented with a view to defining sub-populations of distinct health status within a territory for the purpose of disease control and international trade. Zoning is defined primarily in geographical terms; therefore, in the context of FMD, a free zone or country is a geographically defined area with a distinct sub-population of animals free from FMD. Susceptible animals and their products from FMD-free areas are eligible for trade. Zoning offers an incentive for countries to control FMD and other animal diseases of economic importance. Lesotho is the only country in southern Africa which is recognised by the OIE as FMD free where vaccination is not practised, while Swaziland, Namibia and Botswana have zones which are recognised by the OIE as FMD-free zones where vaccination is not practised (www.oie.int). The Republic of South Africa is working towards regaining the free zone status. Other countries in the region are yet to have officially recognised FMD-free status.

Requirements of maintaining a foot and mouth disease-free zone

Maintenance of the free zone is vital and the zone is also subject to inspection by the OIE, which is the conferring authority and trading partners, to verify that the requirements are adhered to. Generally, the following are basic requirements for maintaining an FMD-free status:

Separation of animals in the free zone from those in non-free zones

A movement protocol to regulate movement of susceptible animals into, within and out of the free zone. Where allowed, movement of susceptible animals and their products must be recorded.

Surveillance

Continuous surveillance (passive and active), with good laboratory diagnostic support is key to proving that susceptible animals in the free zone are free of clinical FMD or infection. The key objective is to detect FMD early and react promptly to contain and eradicate the disease.