17 minute read

Feature

Power Play

After 2020 gains, Republicans are hoping to swing more Latino voters in South Texas. It’s not as easy as it looks.

Advertisement

BY SANFORD NOWLIN

After former President Donald Trump’s surprisingly strong performance along the U.S.-Mexico border in the last election cycle, Republicans have been working overtime to paint South Texas red.

The Republican National Commi ee is undertaking a multimillion-dollar outreach eff ort across the region, which the group is billing as the largest Texas outlay in its history.

To that end, the RNC has opened at least three Hispanic Community Centers in South Texas, including one in Southeast San Antonio, as it pushes to win over Latino votes ahead of the midterms.

What’s more, a GOP Super PAC called Project Red Texas swept into South Texas late last year on a recruiting push that signed up 125 Republican candidates for county offi ces, the Texas Tribune reports. The organization reportedly paid fi ling fees for more than half of those new contenders.

Both eff orts are a bid to build on Trump’s relative success winning over Latino voters in 2020. While Joe Biden handily won the Latino vote nationwide, and in large Texas metros, Republicans latched onto his disappointing performance in the Rio Grande Valley, a longtime Democratic stronghold.

Trump won 14 of 28 border counties that Hillary Clinton virtually swept four years prior. Adding to the sting for Democrats, Clinton won by an average of 33 points across those counties, while Biden’s victory margin narrowed to just 17, according to a Texas Tribune analysis.

“A good part of this is simply that the Republican Party in Texas is wealthy and using some of that money not just in traditional hotbeds but in places where they haven’t traditionally performed as well so they can narrow the margins,” said Cal Jillson, a political science professor at Southern Methodist University in Dallas.

That its outreach is now targeting the Rio Grande Valley should come as li le surprise given the demographics at play, Jillson added. As the Lone Star State shifts younger and less white, the Republican party risks losing its decades-long dominance of state politics.

Political observers say Trump’s message of rejuvenating the U.S. economy and turning back the cultural clock resonated in rural South Texas just as it did in small towns elsewhere in the U.S. The question is whether his second-term performance with border Latinos will prove to be an anomaly or a sign of a larger shift.

In either case, political experts say concern about jobs was the biggest driver of South Texas’ 2020 shift.

Many South Texas Latinos work in the oil and gas industry, and Republicans painted Biden’s pledge to ban new fracking on federal lands as the fi rst step toward banning the practice, used in the region’s Eagle Ford Shale. That messaging came as the pandemic forced Texas oil companies to slash jobs.

Republicans also argue that Democrats’ message about police accountability turned off South Texas Latinos in communities where many work as Customs and Border Patrol agents. Ahead of the midterms, they’re also ramping up messaging blaming the Biden administration for the current surge in border crossings.

Facebook / Javier Villalobos McAllen Mayor

Confl icting signals

MRepublican Javier Villalobos (left) mingles with supporters. He won a runoff in June to become mayor of the South Texas city of McAllen.

Republicans’ new focus on South Texas Latinos comes at the same time as the state party enacted a sweeping new law that makes it harder for Texans to vote — especially people of color. It’s one of many such laws enacted by Republican-controlled states in the wake of Trump’s repeated lies about the last election being riddled with fraud.

If the GOP really thinks it can make big gains with South Texas Latinos, observers ask, why work to minimize their political power?

That same observation isn’t lost on Latino voters, political scientists add. It also comes as those same voters see Gov. Greg Abbo and other Republicans ramp up anti-immigrant rhetoric and militarize South Texas communities to play up their strength on border security ahead of the midterms.

Aimee Villarreal, who heads the Center for Mexican American Studies at San Antonio’s Our Lady of the Lake University, said she sees Trump’s 2020 performance as a unique situation that will be diffi cult for Republicans to repeat.

As Texas digs out from the pandemic’s economic hardships, oil and gas jobs are coming back, she said. Voters along the border are now less likely to look favorably on a party that they see demonizing immigrants and viewing Latinos as second-class citizens.

“The Republican Party is completely misguided, and they’ve completely overplayed their hand,” Villarreal said.

Local outreach

Despite the apparent contradictions at the heart of its strategy, the GOP’s community-based outreach makes sense to some political observers — even some from the opposite side of the aisle.

GOP operatives are billing the RNC’s new community centers as gathering spaces rather than traditional political offi ces. They’re places where families can come together to discuss local issues, hold worship services or drop off the kids for a bilingual movie night.

San Antonio’s center, nestled into a nondescript strip mall containing an appliance repair shop and a convenience store, includes a big-screen TV and a children’s table equipped with crayons. A table by the door is piled with fl yers for local candidates and photos of GOP Latino lawmakers hang along one wall.

“In San Antonio, we did a couple of cryptocurrency trainings, a couple trainings on how to start a business,” RNC Texas spokeswoman Macarena Martinez said. “We’ve also had a food drive where we collected canned goods and gave them to an organization in need.”

Veteran Democratic political consultant Laura Barberena said the new centers seem modeled more after churches than typical party offi ces: they bring people together as a community before slipping in a sermon.

“They have the potential to talk to Hispanic voters about the issue they actually want to talk about,” she said. “What you’re doing is creating relationships with those voters.”

The centers could even help further the party’s push to fi nd strong candidates for local races, Barberena noted. That kind of grassroots growth will be essential if the party wants to build on Project Red Texas’ recent recruiting eff orts.

Likely feeding Republicans’ new interest in local races, Republican Javier Villalobos narrowly won McAllen’s mayoral race in a June runoff . While that city position is offi cially nonpartisan, it was lost on no one that Villalobos formerly chaired the Hidalgo County Republican Party.

For the GOP to be successful in South Texas, its eff orts must be sustained and long-term, which will come with a considerable price tag.

Barberena noted that Republicans’ outreach to Hispanic voters in Texas is nothing new. Former Gov. George W. Bush made inroads on that front, only for the party to slide back after his successor, Rick Perry, appeared to write off South Texas Latinos.

Democratic response

Also key to understanding how the GOP performs in South Texas is how aggressively Abbo ’s likely challenger in the general election, former El Paso Congressman Beto O’Rourke, hits in the region. While O’Rourke is a dogged campaigner, he doesn’t have the resources to be everywhere at once.

Indeed, Democrats’ decision not to campaign door to door while COVID-19 was raging may have contributed to Trump’s improved showing with Latinos on the border, political experts note.

While many pundits predict the 2022 midterms will be punishing for Democrats nationwide, party offi cials said they’re not taking South Texas for granted. The Texas Democratic Party has hired a regional political manager focused on South Texas, and it’s boosted spending on voter registration.

What’s more, progressive-leaning voter mobilization groups such as San Antonio-based MOVE Texas have expanded eff orts in South Texas. The group said it plans to register 50,000 Texas voters between the ages of 18 and 30 ahead of the midterms.

SMU’s Jillson said South Texas is likely to lean Democrat for some time. Just the same, it would be foolish for the party to ignore Republicans’ 2020 showing — and its current outreach plan. If Democrats wants to hold off further red gains among South Texas Latinos, they’ll need to spend big, pound the ground and search for messages that resonate.

“Democrats need to hear the sirens,” Jillson said. “They need to know that something they’re doing in South Texas isn’t working as well as it should.”

CITYSCRAPES

Falling Behind

San Antonio’s endless incentives for Microsoft help explain our lagging economic development

BY HEYWOOD SANDERS

This time of year, it’s traditional for a column to look ahead at the prospects for San Antonio and the larger community going forward. But now, with the eff ects of COVID-19 still looming large, it is diffi cult to see ahead with any certainty.

Even so, looking back off ers us some context for understanding where the city is headed.

Just a couple of weeks ago the Express-News reported on the city’s latest deal with Microsoft for a new data center — a deal granting the company a variance on the city’s tree preservation ordinance. Microsoft will be able to remove more than 2,000 trees from the site in the Westover Hills area, leaving just a small number of large trees. In return, the tech giant proposed planting 800 new ones and paying $1.4 million to the city’s tree mitigation fund.

Bending over backwards to accommodate Microsoft and its data centers has a long history in this town. City council approved a deal in 2007 that gave Microsoft a 10-year property tax abatement for the data center in exchange for the promise to create 75 full-time jobs.

Of course, these data centers are just big buildings that house racks upon racks of computer servers to run Microsoft’s Azure cloud services. They don’t need many employees. In fact, Microsoft shared in documents that 20 of those 75 jobs would be in “site security services” — onsite guards.

Yet, despite the modest number of workers the center planned to hire, local leaders gave it even more incentives via a lucrative tax abatement deal from Bexar County.

“This is not a gift to Microsoft … This is a gift to ourselves,” then-Mayor Phil Hardberger assured the community.

Six years later, Microsoft came back with plans for a $250 million expansion, and the city council — with just one no vote — approved a new, 15-year tax phase-in deal. This time, Microsoft put its job creation at just 20 new jobs.

City staff contended that there would be a “net fi scal benefi t” to the city government, counting sales tax revenue and CPS Energy revenues as well as some property taxes. You see, the city’s share of CPS’s revenues is a signifi cant part of the city budget. And data centers such as Microsoft’s are incredible energy hogs, using electricity at low large-user rates to run those banks of servers 24/7. In 2007, Milton Lee, then head of CPS Energy, contended that Microsoft would be the city’s largest energy user.

Microsoft has continued to invest in data centers here, buying some existing ones and building others, both in Westover Hills and farther west at the Texas Research Park on a 158-acre tract purchased in 2015. The deals with Microsoft were supposed to be the catalyst to boost San Antonio’s future in information technology. But aside from demanding huge amounts of electrical power, it’s not at all clear what the community got aside from a host of massive new buildings in Westover Hills and beyond.

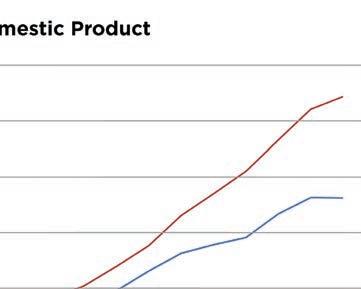

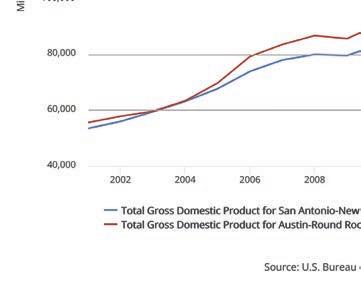

It’s instructive to compare where we are today with our neighbor to the north, Austin. In 2007 and 2008, the average hourly earnings of private employees in metro San Antonio and metro Austin were about the same, at about $23. Average earnings here slowly grew to a li le over $26 by late 2021. But average earnings in the Austin area reached more than $32 at that time.

The diff erence between San Antonio and Austin in terms of overall economic activity, or gross domestic product, is even more striking. While our economies were roughly the same size in 2003 and 2004, the state capital now surpasses us by some 28%.

Our city and county governments signed deals for massive data centers that produced remarkably few jobs — and no real economic spinoff s. Austin has, for years, followed a very diff erent strategy.

Some would argue the comparison is unfair. Austin, after all, boasts a premier public research university and a highly educated labor force. The city has managed to capitalize on a technology economy that demands talented people.

Yet San Antonio’s leaders seem to follow the same old plan and deliver the same promises. We still seem to cling to the hope that new jobs and investment capital will come from afar, and that visitors will be so entranced by the wonders of “tropical” San Antonio that they’ll eventually locate here.

More than 100 years ago, John Carrington, head of San Antonio’s Publicity League and later its Chamber of Commerce, penned an article headlined “One Texas City Advertises Itself Into Prosperity.”

Things haven’t quite worked out that way, and they’re unlikely to work that way in the future.

Heywood Sanders is a professor of public policy at the University of Texas at San Antonio.

CURRENT EVENTS

City council’s handling of COVID rescue funds shows deep-pocketed interests still reign in San Antonio

BY SANFORD NOWLIN

Last week’s vote to jump three well-connected organizations to the front of the line as the city doled out federal COVID-19 relief funds off ered another dismaying look at how public business gets done in San Antonio.

On a 9-1 vote last Thursday, city council approved a distribution plan for $212.5 million in federal pandemic recovery grants made available through the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA). Those funds are vital as the city deals with mental health issues, economic development and other challenges wrought by COVID.

What’s alarming about that vote is that the approved package immediately funnels $32 million of the funds to a trio of infl uential local groups while requiring others — most with fewer resources and political connections — to undergo a lengthy approval process.

Of that special set-aside, $10 million is going to Texas Biomedical Research Institute, a well-funded lab controversial for its experiments on primates; $15 million to Morgan’s Wonderland, a theme park accessible to people with special needs; and $7 million to Educare, a child-care program connected to the Texas A&M-San Antonio campus.

Multiple citizen speakers at Thursday’s meeting questioned why those three organizations, other than their obvious political clout, got to jump the line. Longtime activist Graciela Sanchez of the Esperanza Peace & Justice Center blasted their special treatment as “sweetheart deals” arranged by City Manager Erik Walsh and his staff .

It’s hard to disagree.

After all, there was minimal public input on the decision to give those three groups a leg up. Plus, to Sanchez’s point, they have the fi nances and political heft to lobby council in ways others can’t.

“Maybe it wasn’t slimy, maybe it wasn’t shady, but how does it not look that way?” District 2 Councilman Jalen McKee-Rodriguez asked in an interview following the meeting, during which he cast the only dissenting vote. “How can anybody else look at this and not say the city made some sort of special agreement or deal? Because those conversations were never public.”

The lack of transparency McKee-Rodriguez raises is especially troubling in the case of Texas Biomed, which last year sought an $11 million municipal bond from the city to expand its infrastructure. After overwhelming pushback from residents and animal-welfare groups during public comment, the lab withdrew its request in December. Understandable. To a research institution with 2020 assets of more than $225 million, that funding — while not exactly couch-cushion money — probably wasn’t worth the ugly public fi ght. Especially if there were other ways to secure it.

The $10 million in council-approved ARPA funds now going to Texas Biomed are slated to fund that same infrastructure expansion. Only this time, there were far fewer of those pesky public input sessions to get in the way.

McKee-Rodriguez said he had no recollection of the lab presenting at a December council B Session on the ARPA funds. Many who spoke Thursday against the allotment said they were also surprised when it popped up on council’s agenda.

Mayor Ron Nirenberg and others on the dais had a chance to remedy the appearance of a backroom deal when McKee-Rodriguez introduced an amendment to require separate votes on the expedited funding for Texas Biomed and the other two organizations.

However, his motion failed on a 6-3 vote with one abstention. Nirenberg was among those who rejected it.

At the meeting, citizens and animal-welfare advocates accused the city of giving Texas Biomed a hefty consolation prize after it failed to land the bond money. Given the circumstances, it’s easy to see why they read council’s vote as an end run.

One speaker, 19-year-old Mariah Smith, said she adjusted her work schedule so she could show up at multiple bond meetings to raise concerns about Texas Biomed’s treatment of animals. In the end, it seemed like the lab was destined for a city handout no ma er what.

“This was my fi rst real experience with the city’s public engagement process, and I must say I’m a bit disappointed,” Smith said, in what should be in the early running for understatement of the year.

Nirenberg and council should take note of Smith’s words of frustration. While voiced by someone new to the political process, similar complaints about the city’s lack of transparency, disregard for public input, closed corridors of access and unbridled staff power aren’t new.

Those same grievances drove the fi re union’s success on a punitive 2018 ballot measure that prompted the departure of previous city manager Sheryl Sculley. They also contributed to Nirenberg’s 2019 near defeat by anti-establishment candidate Greg Brockhouse.

San Antonio’s powerful may still enjoy special access, but voters don’t like to be ignored.

Instagram / nutrixorge

13th Annual

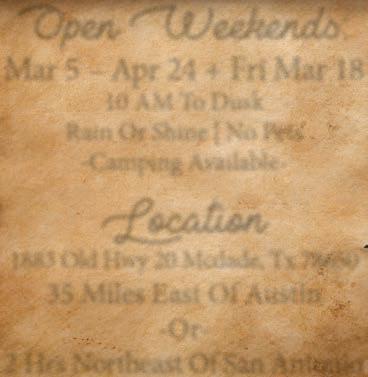

Open Weeken :

Mar 5 – Apr 24 + Fri Mar 18

10 AM To Dusk Rain Or Shine | No Pets -Camping AvailableLocation

1883 Old Hwy 20 Mcdade, Tx 78650 35 Miles East Of Austin -Or2 Hrs Northeast Of San Antonio

Ent tainment

Join Robin Hood & Lady Marian as they host full contact jousting, falconry, swordplay, archery, juggling, comedy, theater & more. Medieval England comes to life in Central Texas. Art a + M chan We host a grand selection of hand-cra ed goods in Central Texas. We o er demonstrations like glass blowing, blacksmithing, pottery spinning, leather armor making, weaving, jewelry & art creation, & others.

Song + Dance

You'll nd minstrels, bards, storytellers, magicians, jugglers, & all types of performers strolling our lanes & playing on our stages. If you're lucky, you may spot a faery or two!

Food + Drink

From trenchers weighty with tasty fare to tankards over owing with foamy mead, there's plenty to eat and drink at Sherwood Forest Faire. You'll discover medieval treats & delicacies.