13 minute read

2.7 Curating Narrative and Experiential Exhibitions

from tame wicked

legibility. The guidelines extended beyond the text on walls to more visual presentations such as signage and interpretive graphics.

The inherently spatial character of narrative and storytelling has influenced curatorial approaches in museums but also at many other different types of cultural venues such as visitor centres, historic sites, entertainment venues, educational environments, sports events, retail destinations, branded environments, corporate events, product launches, urban and community environments. The narrative approach also engenders a highly collaborative approach with distinct disciplines contributing to the narrative process including architects, curators, destination consultants, 3D designers, communication designers, interaction designers, time-based media designers, scenographers, writers, retailers and project managers.262

Advertisement

2.7 Curating Narrative and Experiential Environments

Over the last two decades, the narrative and experiential approach to curating exhibitions has influenced curating practice at a range of institutions. Educational theorists such as Falk and Dierking have commented on the fact that most visitors are drawn to exhibitions that are both visually compelling and intrinsically interesting to them on a personal level. Falk and Dierking’s research in particular, discussed in section 2.2, suggests a sophisticated understanding of the need for both education and entertainment to be intrinsic ingredients of the museum experience.

The education versus entertainment debate has been a long-running debate in the museum sector. For curators they are two ideologically laden terms, as Falk and Dierking have noted; “to the academic, education connotes importance and quality, while entertainment suggests vacuousness and frivolity.” They argue that the area has been something of an epistemological blind spot for some curators who continue to treat the two variables as if they were mutually exclusive instead of

262

MA Narrative Environments Degree Show Catalogue, Central Saint Martins, London, 2015 - 2017: 4-5.

complementary aspects of a complex leisure experience.263

Supporting this argument has been research undertaken into alternative modes of spectatorship, in particular immersive and interactive ways of experiencing visual spectacle and not usually considered part of the canon of design exhibitions.264 The research has assisted in fostering an understanding of the nature of immersive spectacle and the role of theatricality, performance and illusion in shaping the visitor experience. As more exhibitions are studied intensively, many of the traditional perceptions of how visitors uses museums are coming into question, such as not engaging with interactive exhibits or reading text and graphic panels. As Alison Griffiths has noted, “the search for innovative methods of immersing spectators in exhibit spaces has been something of a holy grail for museum curators.”265

In Shivers Down Your Spine: Cinema, Museums & the Immersive View, Alison Griffiths examines less obvious exhibition sites such as the medieval cathedral, the panorama, the planetarium, the IMAX theatre and the science museum as exemplary spaces of immersion and interactivity. Writing within the context of film spectatorship, she argues that spectators first encountered immersive ways of experiencing the world within these environments and by so doing, reveals the antecedents of modern media forms that suggest a deep-seated desire in the spectator to be come immersed in a virtual world. Griffiths’ research marks out the museum as the perfect institutional venue for drawing these ideas into sharp relief. She demonstrates how immersive and interactive display techniques, reconstructed environments and touch-screen computer technology have redefined the museum space. Griffiths clarifies her use of the term immersion:-

263

John H. Falk and Lynn D. Dierking (eds.), The Museum Experience Revisited, London and New York: Routledge, 2013: 114.

264

Important research has been undertaken by Alison Griffiths published as Shivers Down Your Spine: Cinema, Museums & the Immersive View, Columbia University Press, 2013.

265 Ibid.: 250.

“I use the term immersion in this book to explain the sense of entering a space that immediately identifies itself as somehow separate from the world and that eschews conventional modes of spectatorship in favour of a more bodily participation in the experience, including allowing the spectator to move freely around the viewing space.”266

She argues that spectators feel enveloped in immersive spaces and strangely affected by a strong sense of the otherness of the virtual world entered, “neither fully lost in the experience nor completely in the here and now.”267

Oliver Grau provides a useful definition for immersion in his book Virtual Art: From Illusion to Immersion, that links back to Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s concept of ‘flow’ discussed in section 2.2. Grau argues that:“In most cases immersion is mentally absorbing and a process, a change, a passage from one mental state to another… characterised by diminishing critical distance to what is shown and increasing mental involvement.”268

In an interview following the publication of her book, Griffiths was asked to define what she meant by “the immersive view” and why the term was generating so much debate in contemporary culture. She explains that an immersive view is provided by an image or space such as a painting, photograph, film, or museum exhibit that gives the spectator a heightened sense of being transported to another time or place.269 She argues that it is not possible to talk about the immersive view without talking about museums. A great many of the themes uniting immersive spaces are all mobilised in the museum. For Griffiths, museums of natural history deliver immersion on two fronts as they often feature exhibits that re-create natural environments such as the rainforest and also frequently feature

266

Alison Griffiths, Shivers Down Your Spine: Cinema, Museums & the Immersive View, Columbia University Press, 2013: 2.

267 Ibid.: 3.

268 Oliver Grau, Virtual Art: From Illusion to Immersion, Boston: MIT Press, 2003: 13.

269

‘An interview with Alison Griffiths’, Colombia University Press, 2013. Available at: https://cup.columbia.edu/author-interviews/griffiths-shivers-down-your-spine (Accessed 12.07.17).

IMAX screens which are exemplary at delivering immersion. Museums have always relied upon technologies of vision and sound, such as photography, recorded sound, cinema, and electronic images to heighten the gallery experience and to enhance learning and understanding through sensory and emotional appeal.

As Griffiths’ research demonstrates, maintaining the right balance between science and spectacle has been a perennial challenge for the modern museum. There is a strong historical precedent for immersing spectators in the represented space and taking them beyond the ‘here and now’ of the exhibit. Ideas of spectacle and immersion were defining features of contemporary amusements such as panoramas, vast circular paintings popular during the nineteenth century, planetariums and museums of science and natural history that have long exploited the phenomenon. Panoramas, sometimes called cycloramas, were among the earliest and most commercially successful forms of mass visual entertainment. A panorama was a huge 360-degree painting hung along the circumference of an interior wall of a specially designed circular building. At the centre was a viewing platform reached by a flight of stairs allowing the spectator to view the huge canvases that surrounded them. The panorama privileged an immersive mode of spectatorship communicating to audiences that what they were experiencing was unique, memorable and uncanny.

Fig. 23: Cross-section of Robert Barker’s panorama rotunda in London’s Leicester Square, 1793.

Like the panorama, the planetarium experience, which developed during the 1950s and 1960s, takes place inside a dome where a virtual reality is illusionistically constructed. A planetarium show is a combination of the art of the theatre and the science of astronomy. Spectators take their seat in a darkened auditorium and are transported to outer space to see star constellations, galaxies and phenomena such as asteroids and black holes projected onto the dome described by Griffiths as “the upward revered gaze”270 The planetarium as an example of immersive technology combined spectacle, science and popular amusement and offered to the viewer the possibility of escaping out of the present and into another time and space. For Griffiths, there is, therefore, a strong sense of déjà vu in contemporary debates about new media in the museum and the role of immersive and interactive environments.

Over the last two decades in an increasingly digital and interactive age, museums have explored a wide variety of methods and subject matter to

270

Alison Griffiths, Shivers Down Your Spine: Cinema, Museums & the Immersive View, Columbia University Press: 143.

engage with their audiences. Visitors are no longer considered to be passive readers of an exhibition but an active voyager in the exhibition journey. In order to enhance visitor experiences, curators now embrace more spatial interventions such as interior architecture and theatrical installations to transform the museum space into immersive environments. Designed exhibition spaces become a stage for dramas and theatrical effects. As Judith Barry has noted:-

“Increasingly, [there is a] sway of another kind of exhibition design, one designed not simply for display, but specifically for consumption, to cause an active response in the consumer, to create an exchange.”271

This approach has influenced curators working outside the context of the museum. In 2008 interior stylist and designer Faye Toogood founded Studio Toogood to “create environments and experiences that immerse the viewer and communicate concepts through commanding all of the senses.” The studio’s commercial projects include interior retail environments such as the re-design of Dover Street Market, Liberty’s window displays and Tom Dixon’s London showroom. As well as commercial projects, the studio has an international presence at design fairs such as the Salone del Mobile and London Design Festival. In 2009 Toogood created a series of installations of varying scales at London Design Festival. In an interview, she commented:-

“I think there is obviously a time and a place for the “white cube” approach, but I feel that it’s often an overused method, adopted by many, in the hope it will elevate a product and its design credentials beyond its worth. It’s very easy to stick something on a white plinth in a gallery-like environment and hope for the best. Each project that we work on is entirely different and we try to find ways of communicating the value of what is being presented by creating an experience around it - without overpowering it. This approach isn’t about competing with the products but more about inspiring people to poke them, pick them up, sit on them, wear them, walk off with them or simply stare at them.”272

271

Judith Barry, ‘Dissenting Spaces’ in Reesa Greenberg, Bruce W. Ferguson and Sandy Nairn (eds), Thinking about Exhibitions, London: Routledge, 1996: 311.

272

‘2 or 3 questions for Studio Toogood', Moco Loco webarchive, 2012. Available at: https://mocoloco.com/2-or-3-questions-for-studio-toogood/ (Accessed 8.10.17).

In 2012 Studio Toogood designed an installation as a visual antidote to the chaos of the Salone del Mobile. La Cura was conceived as a hospital for the senses in which visitors were invited to rebalance through a series of intimate performances. Participants were seated on a circle of bandaged chairs around a central pavilion where figures in white tended a garden of clay sculptures. They were offered an elixir created by food designers, Arrabeschi di Latte, before being presented with an enamel dish and ball of clay to mould. The 'caretakers' collected each clay sculpture in turn and committed them to the central pavilion where they become part of a collaborative sculpture that grew as the week progressed.

Fig. 24: La Cura: Installation curated by Studio Toogood, Salone del Mobile, Milan, 2012.

Projects like La Cura represent a new form of exhibition practice which uses a site specific installation to promote a deeper engagement with the visitor and enhances understanding of the ideas presented. They can also act as sites for experimentation where a new understanding can be created through the interaction of the visitor which, in turn, feeds back into the practice of the designers.

This new approach to the visitor experience determines a radically different curatorial process to the conventional ‘historical’ or object driven modes of display where significant objects are presented as "design pieces" without any context or story. It looks to the creation of different visitor experiences where the visitor determines relationships between exhibits and make sense of what is on display. The curator offers multiple modes of engagement to inspire an understanding of design concepts and practices, as Paula Marincola has commented:-

“A well-curated show, in fact, is that it seemingly elevates and enriches our experience of all the art that it presents. It provides lesser works with a setting in which they shine, and in which they’re most interesting.”273

Since the late 1990s, exhibitions that exemplified this new approach were often described as ‘blockbusters’, a term more commonly applied to films and not usually associated with art exhibitions. Blockbuster exhibitions were large-scale, popular, moneymaking showcases that delivered a powerful impact. They became important sources of revenue for museums and created visibility and prestige for museums both nationally and internationally. In the early 2000s, the rise of the so-called ‘blockbuster’ exhibition was characterised at the V&A by a series of large-scale international exhibitions that demonstrated this new approach. The exhibition, Art Nouveau 1890 - 1914 (6 April - 30 July 2000) began a series of style exhibitions that included Art Deco 1910-1939 (27 March - 20 July 2003); Modernism 1914 - 39: Designing a New World (2006); Cold War Modern: Design 1945 - 70 (25 September 2008 - 11 January 2009) and Post Modernism: Style and Subversion 1970 - 1990 (24 September 2011 - 8 January 2012). Brian Ferrisa, Director and Chief Curator of the Portland Art Museum, Oregon has suggested that the power of these exhibitions lie in their ability to tell stories by “connecting strong

273

Paula Marincola (ed.), What Makes a Great Exhibition?, Philadelphia: Philadelphia Exhibitions Press, 2006: 44.

ideas to fabulous objects and putting the person in the place and in the space”.274

In 2013 the V&A staged a retrospective exhibition of the musician David Bowie, David Bowie is … (23 March - 11 August 2013). The museum had previously curated exhibitions of living musicians but the Bowie exhibition was singled out by reviewers for its innovative interpretive approach. In media interviews, the curators Victoria Broackes and Geoffrey Marsh, explained that, rather than presenting a traditional chronological exhibition, they had wanted to examine Bowie’s creative process through lateral associations and position Bowie as a figure who was hugely influential in art, design, music, pop culture and society.275 The curators had direct access to Bowie’s personal archive and the exhibition featured a broad range of material that included stage costumes, original hand-written lyrics, album covers and film. They deployed different creative techniques in the exhibition to achieve an immersive effect. Headphones were issued to every visitor so that they were able to listen to Bowie soundtracks which changed as they walked though the installation. Huge inverted set designs and high impact video projections integrated objects and themes into a theatrical environment that was intended to capture the excitement of a live performance.276

The success of the curatorial interpretation was confirmed by reviewers of the exhibition:-

274

V&A Touring Exhibitions promotional trailer. Available at: https://www.vam.ac.uk/info/ exhibitions-for-hire (Accessed 8.10.17).

‘David Bowie Is - an interview with V&A curator Geoffrey Marsh’, Phaidon webarchive,

275 18 March 2013. Available at http://uk.phaidon.com/agenda/art/articles/2013/march/18/ david-bowie-is-an-interview-with-the-vanda-curator/ (Accessed 8.10.17)

Lauren Field, ‘A Portrait in Flesh: An interview with the assistant curator of David

276 Bowie Is’, Un-making Things, 2013. Available at: http://unmakingthings.rca.ac.uk/2013/ david-bowie-is-an-interview-with-the -assistant-curator (Accessed 8.10.17).

“Then, in the final room, you encounter the apotheosis of Bowie, the musician. On huge screens, five times life sized, film of legendary performances plays, with the costumes glittering through the gauze. The sheer grandeur brought tears to my eyes…I can’t believe you will walk away from this stunning exhibition without understanding a little of why he inspired those of us who love him.277

Fig. 25: David Bowie Is…at the V&A London, 23 March - 11 August 2013. Curated by Victoria Broackes and Geoffrey Marsh.

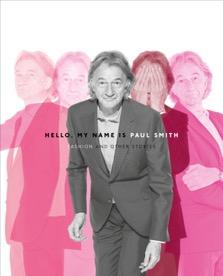

Helen Charman, formerly Director of Learning and Research at the Design Museum, London and now Director of Learning at the V&A, observed a similar strategy at the Design Museum with fashion exhibitions that include Hussein Chalayan: From fashion and back (2009), Christian Louboutin (2012) and Hello, My Name is Paul Smith (2013).278 In her view, each of these exhibitions created an immersive environment, differentiating and distinguishing design curating from Brian O’Doherty’s description of the “white cube” gallery environment, in which “everything but the work itself is expunged in order to provide an unadulterated pure

277

Sarah Crompton, ’David Bowie: the show goes on at the V&A’, The Telegraph, 18 March 2013. Available at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/music/rockandpopmusic/ 9937804/David-Bowie-the-show-goes-on-at-the-VandA.html (Accessed 8.10.17).

278

Helen Charman, ‘x’, in Liz Farrelly and Joanna Weddell (eds.), Design Objects and the Museum, London: Bloomsbury, 2012: 144.