6 minute read

2.5 Narrative Environments

from tame wicked

2.5 Narrative Environments

The previous section (2.4) has explored how curators have sought to understand how visitors learn in exhibitions and applied this understanding to construct appropriate visitor experiences. A number of museum theorists have suggested using the framework of a narrative approach as a way to enhance the ways in which visitors engage with spaces, concepts and objects.240 The idea has become a powerful and persistent idea for many curators working in museums and has influenced my own approach to curating, to be discussed more fully in Chapter 4.

Advertisement

In her study, From Knowledge to Narrative: Educators and the Changing Museum, published in 1997 Lisa Roberts explores how museum educators have become central figures in shaping exhibitions and displays. They construct narratives based less on explaining objects and more on interpreting objects which are determined as much by what is meaningful to the visitor as by the curatorial intention. Roberts discusses museum education in relation to entertainment, which in her view can be understood as “a tool of empowerment, as a shaper of experience and as an ethical responsibility.”241

This approach derives from a simple idea that humans are natural storytellers. Psychologist and educator, Jerome Bruner, has argued that since ancient times, humans have used stories that represent an event or series of events as ways to learn.242 He suggests that humans employ two modes of thought each providing distinctive ways of ordering experience and constructing reality; paradigmatic (or logico-scientific) and narrative.

240

Key texts include; Lisa C. Roberts, From Knowledge to Narrative: Educators and the Changing Museum, Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press; Suzanne Macleod, Laura Hourston Hanks and Jonathan Hale (eds.), Museum Making: Narratives, Architectures, Exhibitions, London: Routledge, 2012; John H. Falk and Lynn D. Dierking, Learning from Museums: Visitor Experiences and the Making of Meaning, Lanham, MD: Altamira Press, 2000.

241

Lisa C. Roberts, From Knowledge to Narrative: Educators and the Changing Museum, Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997: 79.

242

Jerome Bruner, Actual Minds, Possible Worlds, Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press, 1986: 11-14.

He recognises imaginative narrative as leading to “good stories, gripping drama and believable historical accounts. It deals in human or human-like intention and action and the vicissitudes and consequences that mark their course, and strives to locate the experience in time and place.”243

Philosopher and literary theorist, Roland Barthes suggests that stories are an integral part of our experience as human beings. For Barthes, narrative “is present at all times, in all places, in all societies; indeed narrative starts with the very history of mankind; there is not, there has never been anywhere, any people without narratives; all classes, all human groups have their stories…”244

A number of museum theorists have identified this idea in museums. In Museum Making: Narratives, Architectures, Exhibitions, Laura Hourston Hanks, Jonathan Hale and Suzanne Macleod argue that what unites many curators approaches is an attempt to create what might be called “narrative environments”, experiences which integrate objects, spaces and stories of people and places as part of a process of storytelling that speaks of the experience of everyday and a sense of self:-

“Whereas storytelling in literature is determined and confined by the linear arrangement of text on a page; in cinema to visual images on a screen; and in traditional theatre to the static audience with its singular perspective, the museum represents a fully embodied experience of objects and media in three-dimensional space, unfolding in a potentially free-flowing temporal sequence.”245

In the years leading up to the millennium, museum professionals debated trends in exhibition design and spoke increasingly of the need to contextualise the objects on display for visitors. In 2001 museum consultant Leslie Bedford advocated narrative as a powerful way for

243

Jerome Bruner, Actual Minds, Possible Worlds, Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press, 1986: 11-14.

244

Roland Barthes, ‘An Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narrative’, New Literary History 6, no. 2, 1975: 237.

245

Suzanne Macleod, Laura Hourston Hanks and Jonathan Hale (eds.), Museum Making: Narratives, Architectures, Exhibitions, London: Routledge, 2012. xxi.

museums to engage their visitors, proposing that storytelling is the “real work” of museums. Bedford examined the ways in which the narrative or story form can generate personal connections between visitors and content. Through a discussion of case studies of exhibitions, public programmes and outreach to schools, she argues that stories aid humans in defining their values and beliefs and allow the visitor to make connections between museum artefacts and their own lives and memories:-

“Stories are the most fundamental way we learn. They have a beginning, a middle, and an end. They teach without preaching, encouraging both personal reflection and public discussion. Stories inspire wonder and awe; they allow a listener to imagine another time and place, to find the universal in the particular, and to feel empathy for others. They preserve individual and collective memory and speak to both the adult and the child.”246

Bedford proposes that narratives are key to the process of memorising, retrieving and retelling knowledge. This is particularly important for the educative role of the museum as John Falk and Lynn Dierking also suggest; “universally, people mentally organise information effectively if it is recounted to them in a story or narrative form.”247

In 2004 Sue Allen, a former Director of Visitor Research and Evaluation at the Exploratorium in San Francisco, researched the use of narrative tools as ways for visitors to make meanings about science. Allen defined narrative in a museum context as taking the personal perspective involving a series of events; containing emotional content and authentic in origin, with someone telling the story. Allen also drew attention to the fact that the museum sector still does not clearly understand how narrative could be used to enhance visitor learning.248

246 Leslie Bedford, ‘Storytelling: The Real Work of Museums’, Curator, 44(1), 2001: 33.

247

John H. Falk and Lynn D. Dierking, Learning from Museums: Visitor Experiences and the Making of Meaning, Lanham, MD: Altamira Press, 2000: 51.

248

Sue Allen, ‘Designs for Learning: Studying Science Museum Exhibits That Do More Than Entertain’, Published online in Wiley InterScience, 7 April 2004. Available at: www.intersceince.wiley.com (Accessed 5.04.17).

The traditional image of museums as repositories of artefacts characterised by a linear, encyclopaedic display has gradually given way to a narrative structure devised by the curator with an exhibition designer brought in to create varied rhythms and levels of intensity. Art and media theorists, Anna-Sophie Springer and Boris Groys have likened the role of the curator to that of a cartographer. Like maps, curatorial projects are social constructions, “narrative spaces”, that shape our understanding of place and space. In Boris Groys’ view:-

“Every exhibition tells a story by directing the viewer through the exhibition in a particular order; the exhibition space is always a narrative space.”249

The concept of narrative has extended into the museum as an interpretation strategy and a means of creating links between the subject of an exhibition and the audience. As recent educational theories discussed in section 2.2 have served to highlight, while interest and curiosity may first attract a museum visitor to an exhibit, the interaction with the exhibit has to be intrinsically rewarding in order to enable positive emotional or intellectual changes to occur. For the design exhibition, the idea of narrative alludes to the power of stories as structured experiences unfolding in space and time in which visitors are encouraged to participate and construct their own learning. An interaction is structured around stories, rather than objects and the narrative is essential in the meaningmaking, understanding and remembering of the messages, content and information presented. The exhibition can be perceived as a theatre with narrative potential, a site where space and objects merge to connect with human perception, imagination and memory.

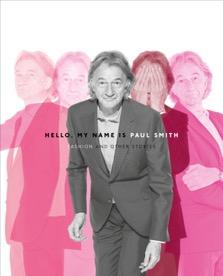

Over the last two decades, a number of exhibitions have served to highlight the prominent idea of curating as a form of storytelling articulated

249

Boris Groys quoted in Anna-Sophie Springer, ‘The Museum as Archipelago’, Scapegoat: Landscape, Architecture, Political Economy, No. 05, Summer/Fall 2013: 247. 151