6 minute read

Vet Vibes: Worming – what you should know

VET VIBES

Worming: What you should know

Without proper management, worm burdens can lead to health problems. RACHEL ROAN spoke to Dr Calum Paltridge to find out more.

Many horse owners are divided about how regularly to worm. Some worm by the book, others wait for signs their horse is wormy, while others only worm when they remember to get around to it.

But how often should you worm? How do you tell if your horse needs it? And how does your horse acquire worms in the first place? To answer your worm-related questions, I spoke to veterinarian Dr Calum Paltridge. Calum has practiced for nearly 10 years and has specialised as an equine veterinarian since 2019.

While many people believe that physical signs such as a pot belly, poor coat, or rubbed tail are signs of a wormy horse, that’s far from accurate. “A lot of horses and may not show any signs at all,” Calum says. “In fact, horses with some of the highest worm burdens I’ve ever seen have been fat, shiny, and healthylooking.”

For this reason, it’s recommended that for an accurate diagnosis you invest in a faecal egg count (FEC). Taking a FEC sample is as simple as collecting fresh manure from your horse. It doesn’t need to be warm, but it does need to have some moisture in it. Your vet will mix the manure with a solution that causes the worm eggs to float to the surface.

The next step is to calculate approximately how many eggs there are per gram of manure, which indicates the worm burden. “A faecal count is really the only reliable method to determine how many worms a horse has in their system,” Calum explains. “A lot of people underestimate the value of a FEC, which can be a very useful tool.” Most faecal egg counts will contain strongyle eggs. Small strongyles (also known as cyathostomes) are the most common type of worm, and most horses have been infected with them at some point in their life.

A low FEC sits between 0-100, medium ranges between 100-500, and a high count is anything over 500. Many vets recommend only worming horses with an egg count over 500, unless the horse is displaying other signs of ill-health such as a rough coat or weight loss. By only worming your herd’s high shedders (horses who shed more eggs into the environment), you reduce the chances of worms developing resistance to different types of treatments. You also reduce the chances of low-shedding horses picking up worms.

A FEC is relatively inexpensive, costing on average between $30 and $50, and may save you from wasting money on regular worming if you’re one of the lucky horse owners with a naturally lowburdened horse – in which case worming once a year might be sufficient. It’s a winwin scenario: you save on wormer you don’t need, and prevent over-worming at the same time. And although most wormers have a generous leeway when it comes to the dosage safety margin, it’s preferable to stick to the recommended dose per weight.

In Australia, there are two main classes of drench. Calum suggests looking for the mectins (abamectin, ivermectin, moxidectin), and the azoles (benzimidazoles, or BZs, such as oxfendazole or albendazole). “There’s a high resistance to the BZ class drenches, so we have to be really careful,” Calum tells me. “With the vast majority of small strongyles in this country resistant to BZ drenches, we’re rapidly heading to a point where we’re not going to have drenches that work at all.” Over-worming is another factor in drench resistance, which is becoming a significant problem in the equine industry.

Mature adult worms live in the horse’s gut, and eggs pass out in the manure. The larvae hatch in the pasture and crawl up the grass, which is then picked up by the horse as it grazes. Larvae can travel a fair way from the manure pile where they hatched, and the more manure in the paddock, the more likely it is that your horse will pick the larvae up.

How well worms thrive depends on the conditions and time of year. In areas prone to frosts and cold weather, worms will often die on the pasture. Similarly, really hot, dry conditions are not worm friendly either. Small strongyles are the most common worm found in Australia, and while they can cause diarrhoea and protein loss, they are not usually life-threatening. Other species, like large strongyles, which are less common in Australia, can cause significant issues including colic, and in some cases, neurological issues have been reported. “They’re the

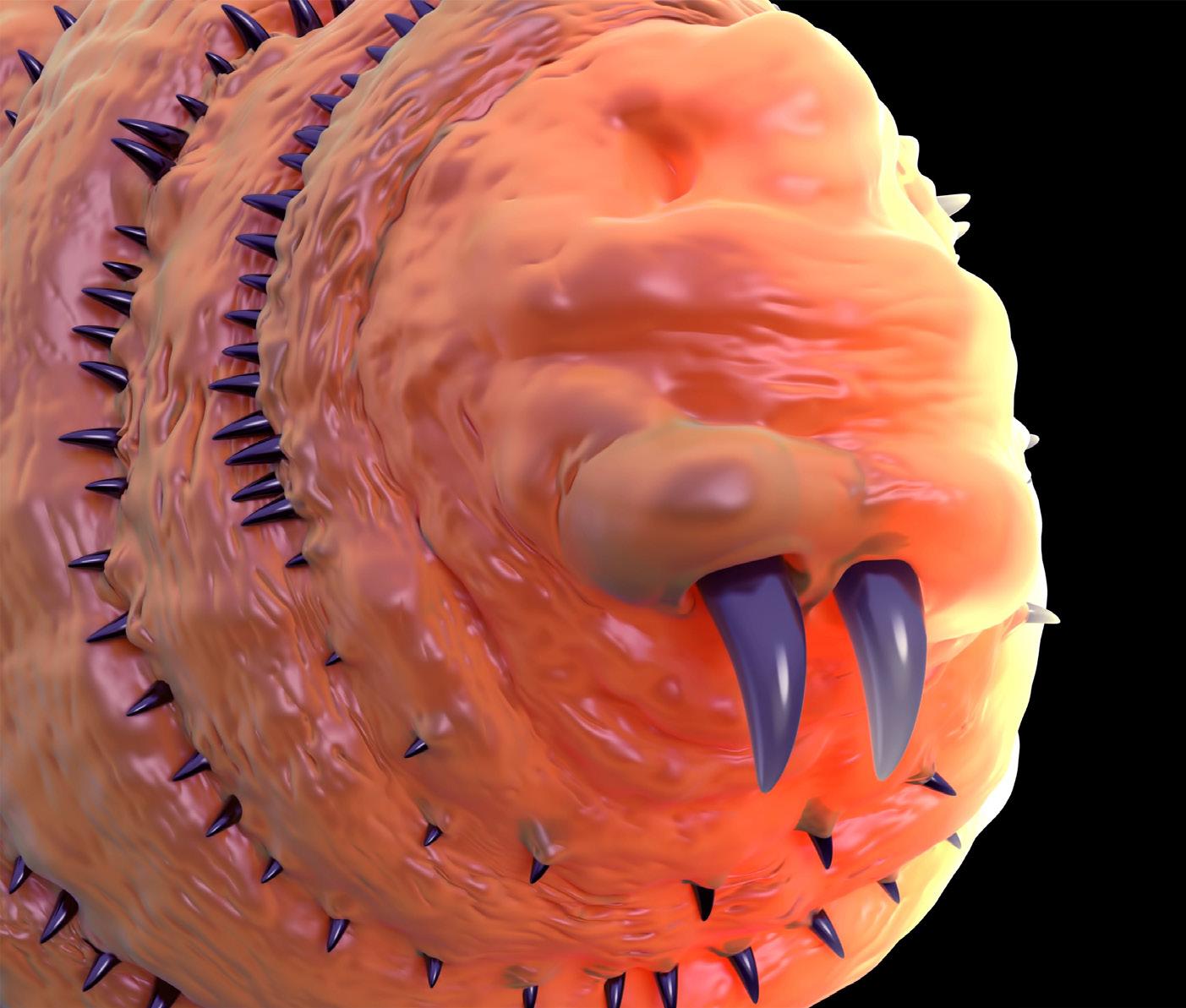

FACING PAGE: Courtesy College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Illinois. TOP: Tapeworms can cause colic even in relatively low numbers. BOTTOM: Bot fly larvae use mouth hooks and spines to attach themselves to mucous membranes and the stomach lining.

Ascarids, also known as small intestinal roundworms.

number one concern, but fortunately we don’t see a lot of them in our country,” Calum says. Tapeworms can also cause colic, even in relatively low numbers, so it’s important to worm so the high shedders don’t pass on worms to horses in your herd that are not as resistant.

Unlike some worms, bots won’t usually cause significant issues with your horse. “When we scope looking for ulcers, we nearly always see bots in the stomach, particularly in the spring and summer months,” says Calum. In horses with a high worm burden, bots can contribute to protein loss, and cause discomfort that will impact performance, so the best advice is to treat them with a mectin based wormer.

Calum believes that mectin drenches are the most effective these days, killing bots, strongyles and external parasites. Comparatively, azole drenches are less effective on small strongyles. However, they are useful for treating ascarids, a type of worm commonly found in foals and weanlings, but not often seen in older horses. A high burden of ascarids can pose significant issues for young horses, causing blockages that the animal may struggle to pass.

Keeping this information in mind, Calum has some advice on a year-round strategy for managing worms.

After worming your horse, move them off that pasture onto a fresh paddock.

Harrow your paddocks to break down manure, exposing the worm larvae to the elements to dry them out and kill them.

Run a different species (sheep or cattle, for example) through the paddock before or after horses. They will pick up the horse worms without it affecting them.

Get a faecal egg count at least annually and rotate your drench to avoid resistance.

While an annual FEC is better than none, testing three to four times a year is the best management tool. Pasture rotation and keeping your pastures clean by regularly collecting manure can be another effective strategy, however FECs are still needed. “Theoretically, it’s possible to control worms through pasture management, but those high shedders often still need to be wormed,” says Calum. “Some horses seem to have more immunity to worms. In a group of 10 horses managed identically, there will be some that always have low counts and don’t require worming, while others have high counts regardless of what you do. There are many factors – it really comes down to the individual horse.”

By implementing a consistent approach to worm management, you can be confident that worms are one less thing for you to worry about. And if you see your horse scratching its tail, or notice a dull scruffy coat developing, don’t just jump to the conclusion that your horse is wormy. Get a faecal egg count first!

Dr. Calum Paltridge (BVSc (Hons) MANZCVS) is the owner and veterinarian at Thunderbolt Equine Veterinary Services in Armidale, NSW.