4 minute read

Veteran Alumnus Shares Memoirs

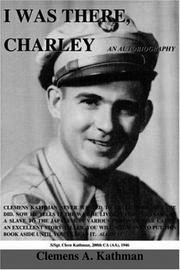

Memories of war often haunt a person who was a part of it. For Clemens Kathman, the memories of the Bataan Death March, prison camps and his trip home will remain with him for the rest of his life. Kathman wrestled his demons in the cathartic process of writing his memoirs — a 2005 autobiography called I Was There, Charley. “I wanted to get things off my chest,” Kathman said.

Kathman, 93, was born in Richland, graduated from Eastern New Mexico University (AA37) and was prisoner of war in World War II. He was drafted into the U.S. Army in March 1941 as a member of the New Mexico National Guard’s 200th Coast Artillery. In September 1941, he was shipped to Clark Field in the Philippine Islands. The Americans and their Filipino allies, half-starved and existing on one-eighth rations, had nothing to fight with but 1903 Springfield rifles, facing the might of the Japanese tanks, bombers and field artillery, Kathman said. His unit was ordered to surrender and started painting POW letters around the camp to let the Japanese know. The soldiers were taken to Canbanatuan after the long Bataan Death March. This was before other prisoners were taken to Camp O’Donnell. Kathman was assigned to a work detail a few weeks after being brought to the camp. About 60 people worked on the clean-up detail, and they had living quarters, food and water. Kathman contracted malaria. Since he was sick, the Japanese wanted to keep him away from the healthy workers. Once Kathman recovered he was re-assigned to another group, but he was able to talk to one of the men. “I got to talk with some of the guys who were on that work detail,” Kathman said. “They said it was good work. They had nice quarters and good food.”

Before long, Kathman and other prisoners were taken to Japan to help the Japanese war effort by working in the factories, on ships, transporting things or cleaning up. “They weren’t suppose to do that, but who was going to tell the Japanese not to do that?” Kathman said. “They took some of the POWs down to the southern islands. I was working in a steel mill, which really was a no-no, because we were manufacturing steel armaments.” After one of the camps was bombed with napalm, the Japanese started breaking the camps into smaller groups of men. During this time, Kathman was on the sick list because his appendix ruptured so he was shipped to another camp, with the sick and wounded. “An American doctor who was there at the camp took a straight razor and cut me right above my hip,” Kathman said. “He did this so (it) could be drained from a rubber hose he stuck in the wound.” Three hundred men were sent and about half of them were sick or wounded from the napalm burns Kathman said. The Japanese let him rest for a few days before he was put on another work detail to unload food off of ships and barges. The Japanese surrendered and started working on sending all the POWs back home on trains to be taken to American ships out in the harbor. Kathman remembers his journey home was a little different because he had to stay in a hospital for 14 months before he was finally able to enjoy his time being home in the U.S.

While in the hospital, Kathman had his first thought about writing his story because everybody was writing books about their experience of being a POW. “After I got out of the hospital, things got a little hectic so I put the book on the back burner,” Kathman said. “I think I wrote a couple of chapters after I got out of the service, which was a 120-days duty at home. Then I got married, and I put it way back on the back burner.” Kathman’s second wife talked him into writing the book and his third wife made him finish it.