16 minute read

Ringside Magazine Playlist

I’m Mallory Bowers from Lafayette, Indiana and I raise Southdowns with my family under Bowers Southdowns. I am currently at Lincoln Land Community College studying Agribusiness and on the livestock judging team, and will head to Purdue after next year.

Advertise In Ringside Today

Advertisement

*NEW PRICING FOR 2023

Please note we do not charge a subscription fee and run this based on ad sales!

Reach out to Cruz, Emily or Morgan, or email ringsidesheep@gmail.com to reserve your space today!

Ad Pricing

FULL PAGE $600 | FRONT COVER $700

1/2 PAGE $450 | BACK COVER $700

1/4 PAGE $350 | INSIDE COVERS $650

1/8 PAGE/BIZ CARD $175

• 10% discount for print ready ads provided by deadline

Mallory’s Top Ten

1. This Damn Song- Pecos & The Rooftops

2. Ramon Ayala - Giovannie & the Hired Guns

3. Billy Stay- Zach Bryan

4. Temporary Town - Charles Wesley Goodwin

5. Freeze Frame Time - Brandon Rhyder

6. Texas Rain - Seven Miles South

7. Criminal - Eminem

8. Tornado - Wynn Williams

9. Ringling Road - William Clark Green

10. Kerosene - Miranda Lambert

MID-STATES WOOL GROWERS COOPERATIVE CLOSING IN 2023

One of the country’s major wool buyers is closing its doors later this year, citing the woeful state of the wool markets and rising costs.

Mid-States Wool Growers Cooperative, based in Canal Winchester, Ohio, sent a letter to its customers last week saying it would stop accepting wool May 1. The letter said the board of directors decided to close in 2023.

“The wool marketing season of 2022 was your cooperative’s worst marketing season since the wool glut of the 1990s. With rising costs and no market for the wool that our producers send in, the difficult decision was made,” the letter stated.

Mid-States sells about 1.5 million pounds of wool each year from its 3,000 members from across the country. It has bought in wool from more than 30 states, as far west as Arizona and New Mexico.

No Market

The wool market collapsed at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, but it had been on the decline for years, said Dave Rowe, general manager for Mid-States.

A penny a pound is what farmers will get for their wool these days, Rowe said. Fine staple wools, the type that is made into clothing, may bring in up to 50 cents per pound. That’s compared with five or 10 years ago when medium grade wool could bring in up to 50 cents per pound and fine wool brought in up to $1.70 per pound.

“It’s got to be able to go against the skin,” Rowe said, for farmers to get a good and fair price for their wool. “The comfort factor with coarse wool is nowhere near what is deemed acceptable, or even excellent.”

Coarse wools have struggled to find “not even a market, but just an interest in it,” he said. Coarse wools used to be used in some clothing, like socks, but now are mostly sold for industrial uses, like pads, absorbents and insulation.

That’s most of what’s produced from commercial flocks in the Eastern U.S., said Melanie Barkley, extension educator with Penn State University. The U.S. as a whole doesn’t do a good job at producing marketable wool, she said. Much of the wool is average to lower quality.

History

Mid-States has been around for more than a century. It began as Tri-State Wool Marketing in 1918, serving Kentucky, Indiana and Ohio producers from its warehouse in Cincinnati. In 1921, the co-op purchased a warehouse in Columbus and became known as Ohio Wool Growers Cooperative Association.

In 1974, Ohio Wool Growers Cooperative Association merged with Midwest Wool Marketing Cooperative, which was organized in 1931 in Kansas City, Kansas, to become Mid-States Wool Growers Cooperative. Mid-States moved to its current location in Canal Winchester in 1995.

Seven people are employed by the cooperative. It’s not clear what will happen once they finally close later this year, Rowe said. The cooperative will hold a meeting of its members in the near future to decide formal next steps.

“We have a great appreciation for our customers and our members,” Rowe said. “That’s going to be the hardest thing for us is not having interaction for them and being able to be a source of help for them.”

The cooperative is still sitting on about half a million pounds of wool in its warehouse, which it will continue to market. Rowe said Mid-States is keeping its supply department open for the time being, focusing strictly on animal health products. It’s in the process of selling out of show equipment.

Challenges And Opportunities

The difficulty in selling wool is nothing new to U.S. sheep producers, but losing this major market will put more of a strain on the industry. Many farmers have been storing wool, waiting for the market to recover.

There are a couple other larger buyers of wool across the eastern U.S., Barkley said.

“People might need to market it locally,” she said.

There may be an opportunity for smaller wool processors to fill a niche, Barkley said. For example, home improvement retailer Lowe’s will start selling wool fertilizer pellets in March produced by Utahbased Wild Valley Farms.

For larger producers, Rowe said they may need to adapt their flock to the wool market if they want to see a return on their fleeces. Right now the money is in fine wool that is used in clothing and apparel.

That might mean using fine wool ewes or crosses in their meat flocks to produce better quality fleeces, “and whatever the market is for your lambs, that’s the ram you use,” Rowe said.

“Listen to the market,” he said. “The market will tell you what it wants. That’s ultimately your best signal for demand.”

(Written by Rachel Wagoner. Sourced from: https:// www.farmanddairy.com/news/mid-states-woolgrowers-cooperative-closing-in-2023).

Sheep And Lamb Inventories Lower

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Agricultural Statistics Service released this week the annual sheep inventory report which stated that all sheep and lambs were down less than 1 percent (0.9 percent) or 45,000 head to 5.020 million head. The breeding flock of ewes 1 year and older was reported at 2.870 million head, down 1.4 percent or 40,000 head.

At the state level, most Southwestern states reported declines while some states in the middle of the country saw increases in the breeding flock. Texas reported a 5,000 head (1.2 percent) decline from the prior year to 425,000 head. California saw the largest decline in breeding ewes with a 9.3 percent or 25,000 head decrease from a year earlier to 245,000 head. Wyoming fell 10,000 head (4.7 percent) to 205,000 head while Colorado was at 153,000 head, down 2,000 head or 1.3 percent.

The American lamb crop as of Jan. 1, was reported at 3.110 million head, down 50,000 head or 1.6 percent from a year ago. California reported the largest decline of 25,000 head or down 10.4 percent to 215,000 head. Wyoming fell 10,000 (4.2 percent) to 230,000 head. Texas, Colorado and Idaho each fell 5,000 head to 345,000, 175,000 and 140,000 head, respectively. Montana fell 8,000 head, while South Dakota and Oregon held steady with the same levels from a year ago.

The national average lambing percentage held steady at 106.9 percent, which is in line with the historical average during the last 10 years. California saw a steep decline in lambing percentage from 96 percent in 2021 down to 79.6 percent in 2022. Texas saw improvement to 80.2 percent while most Northern states held averages well above the national average.

Total market sheep and lambs were even with the prior year at 1.355 million head. Of the market lamb categories, the under 65 pounds and 65 to 85 pounds were down 2.9 percent and 2.1 percent, respectively, to 335,000 and 180,000 head. These declines were offset by gains in the 85 to 105 pounds and more than 105 pounds categories, which were 270,000 and 470,000 head, respectively, up 4.9 percent and 0.9 percent from the prior year.

With the supply of market sheep and lambs even with a year earlier, remaining current on marketings through the year will be critical to balance supply with demand.

Source: Livestock Marketing Information Center

Shearing Schools Set For Spring

There are a handful of sheep shearing schools available to prospective shearers in the next three months. If you’ve considered learning to shear, now is the time to look into signing up because many of these schools will fill up fast.

• Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Mo., will host a shearing school on March 1-2. Contact Extension Associate Amy Bax at BaxA2@LincolnU.edu to register.

• The New York Sheep Shearing School is March 11-12 at the Stone & Thistle Farm in East Meredith, N.Y. For more information, visit www.lambshoppe. com/events/ny-sheep-shearing-school-2023.

• The Moffat County Sheep Shearing School in Craig, Colo., is set for March 31-April 2. Email Megan Stetson at stetson@colostate.edu for more information.

• The Washington State Shearing School will be April 3-7 (beginners) and April 8 (advanced) at the Grant County Fairgrounds in Moses Lake, Wash. For information, visit wsu.edu/grant/livestockanimalscience/washington-state-shearing-school/.

• The Tennessee Sheep Producers Association Sheep Shearing School is scheduled for April 7-8 at Middle Tennessee State University in Murfreesboro, Tenn. Contact Leann Frazer at 615-594-3694 or leelgal@yahoo.com for more information.

• There will be two separate sessions of the Sheep Shearing and Basic Care 101 course at the University of California Research and Extension Center in Hopland, Calif. The first session is April 9-15 and the second session is April 16-

Continued on page 14

22. Contact Hannah Bird at 707-744-1424, ext. 105 or email hbird@ucanr.edu. Visit hrec.ucanr. edu/?calitem=546335 for more information.

• Shepherd’s Cross in Claremore, Okla., will host a shearing school on April 13-15. Visit shepherdscross.com to register.

Source: https://www.sheepusa.org/newsletter/ february-3-2023

How To Save Hypothermic Lambs

In winter lambing flocks, hypothermia and starvation of newborn lambs can account for nearly all of the pre-weaning death loss of lambs. It’s a serious problem that can often be minimized through careful management of the ewe flock and its environment.

Even under the best management in the best environment, there will still be some cases of hypothermia and starvation in most winter lambing flocks. With attention to detail, hypothermia and starvation can be reduced to very low rates even in flocks that lamb in the dead of winter in very cold climates. In most sheep production systems, the majority of the cost of producing a lamb is already spent when the lamb is born (in the form of feed and keep for the breeding flock), so saving chilled lambs is an important way to protect your investment. Preventing it from happening in the first place is even more important.

When it does happen, it’s important for shepherds to know how to recognize, treat, and, most importantly, learn from each case. In most cases, the problems that lead to hypothermia and starvation are difficult to fix during lambing. They can go back months to the level of nutrition in early gestation, or to barn design, or the availability of bedding. That’s why it’s important to keep records about the causes of any hypothermia cases. Once lambing is over, it’s easy to put those problems out of your mind and forget to fix them for next time. Make a habit of keeping good laming records and reviewing them well before the next breeding season so that you have time to make any changes or cull any ewes to reduce problems in the next lambing. In the meantime, you need to try to save as many cold lambs as possible. Here’s a step-by step guide to the process. The goal of this guide is to help you make sound decisions about how to treat a lamb when you’re tired, busy, and probably a little upset. All the steps are aimed at getting the lamb back with its mother as soon as possible, and are based on the assumption that the mother has adequate milk and has not rejected the lamb. If that is not the case, the lamb will need to be grafted or raised as an orphan, but the initial intervention steps are the same.

Understanding Hypothermia And Starvation

In newborn lambs, these two go hand in hand, and left unchecked they fuel one another leading to the death of the lamb. When a lamb is born, it has a reserve of brown fat that releases a tremendous amount of energy during the first few hours of life, keeping its blood sugar high and providing it with enough food to jump start its metabolism.

During these first few hours, the lamb must start to take in the ewe’s colostrum in order to sustain its metabolism and keep itself warm. But digesting food takes energy, and that’s another role that the brown fat plays. If the lamb doesn’t have enough brown fat, or if it doesn’t get colostrum before the brown fat’s energy is all used up, its metabolism can slow down to the point where it can’t digest colostrum. It starts to get cold, and loses more energy. The cycle starts to fuel itself — the lamb lacks energy because it’s chilled, so it doesn’t get the energy it needs to get warm. The shepherd must intervene, or the lamb will die.

Recognizing A Chilled Lamb

As with most interventions, the earlier the shepherd spots the problem and responds to it, the more likely he is to be successful, and the less time and effort will be required to achieve the success. Spotting a lamb that is just starting to have trouble is a key skill. Things to watch for include a hunched posture, hollowed out sides, excessive calling, lethargy, and dehydration. If you pinch a lamb’s skin over the spine, it should snap back almost instantly. If it stays in place like a tent, the lamb is dehydrated and probably needs attention.

In many cases where hypothermia-starvation is in its early stages, all that’s required is to make sure that the lamb gets a good suck from the ewe. The ewe’s teat may be plugged too tightly for the lamb to start the milk flow, or the lamb may have had difficulty finding the teat. If the lamb starts to suckle with assistance, you can often postpone any further intervention and monitor the situation closely to ensure that the lamb and ewe are going smoothly.

Any lamb that is unresponsive or laying flat out on its side requires immediate attention. Perhaps the best way to learn to recognize a chilled lamb is to watch the behavior of lambs that are doing just fine. There’s an indescribable look to a wellfed and happy lamb, and once you know it you will have little trouble spotting the ones that lack it.

Caring For The Ewe And Other Lambs During Intervention

If a lamb needs to be removed from its mother, the dam should be left penned by herself where she cannot try to claim other lambs. If a ewe has more than one lamb, consider removing not just the chilled lamb, but all of them. The process of warming a lamb can take several hours, and during that time, a ewe may forget about one of her lambs. She will not forget about all of them. However, you must return the nonchilled lamb or lambs to the dam to suckle regularly –probably every 20 minutes to half hour.

When the chilled lamb has recovered and can be returned to its mother, it will still need to be watched closely for a day or longer. It’s often easiest to pen the ewe in a location that will be convenient for these frequent checks at the beginning of the intervention.

Necessary Skills

There are also two techniques discussed here that require some training and skill: feeding by stomach tube and administering glucose by intraperitoneal injection. Done incorrectly, either procedure can kill a lamb. I recommend stomach tube feeding of chilled lambs for several reasons. First, it’s a much surer method of getting the required amount of milk into a lamb than attempting to feed it from a bottle with an artificial nipple. Second, It will take less of the shepherd’s time (which is always in short supply when these things happen) and third it can be accomplished even on a lamb that is totally unwilling to suck. Perhaps most importantly, it doesn’t interfere with the lamb’s understanding that food comes from its mother’s udder. A lamb trained to an artificial nipple will stop seeking its mother’s teat at some point.

Most shepherds who have tried both prefer rigid catheters to flexible ones for stomach feeding. A 60 or 120 cc catheter-tipped syringe is also essential. Remove the plunger and catheter from the syringe. Have the milk on hand and warmed to the appropriate temperature. Work the catheter down the lamb’s throat and into the stomach, then attach the syringe and pour the milk in. Allow the milk to flow by gravity — do not force the milk in. If you’re using colostrum and it’s too thick to flow, add just enough warm water to get it flowing. Do not use hot water, or the immunoglobulins in the colostrum will be destroyed.

IP dextrose injection is a bit more complicated. The most straightforward explanation I’ve seen comes from the Alberta Lamb Producer’s Association. The Alberta site makes reference to a typical 4.5 kg lamb, which is about 10 pounds. Adjust the dosage so that your lamb gets 5 ml per pound of the 2:3 solution of dextrose and freshly boiled water (see chart). In the interest of sanitation and sharp needles, I like to use two brand new needles: one for drawing up the solution, and one for the injection.

Necessary Equipment

The key to this whole procedure is a warming box. The warming box is a contraption that can be simple or complicated, as long as it provides a constant, gentle heat to the lamb. I have rigged up hair dryers blowing into dog crates. Some pasture lambing operations use insulated coolers with hot water bottles. The main thing is that you don’t want to heat the lamb directly; just keep it in a very warm and dry environment. Heating a lamb too fast can be just as lethal as leaving it cold.

Things Not To Do

Don’t submerge a lamb in warm water. This common trick may work sometimes, but it will wash the scent off the lamb making it less likely that the ewe will reclaim it, and it will generally heat the lamb too quickly. Don’t warm a lamb with low blood sugar. This can send the lamb into convulsions and kill it. Don’t overheat a lamb. Warming a lamb too quickly or to too high a temperature can kill. Don’t feed a cold lamb. A hypothermic lamb can’t digest milk or milk replacer, and the food will cause digestive problems as it sits in the stomach.

Things To Do

Step 1. Evaluate: Determine lamb’s age: is it more or less than five hours old? Determine lamb’s body temperature. Determine lamb’s general condition: able to stand, suck and swallow? Unable to swallow? Unable to stand? Dry the lamb if it’s wet.

Step 2. Act: If the lamb’s temperature is over 99 degrees F., regardless of age: collect milk or colostrum from the mother if possible to use in feeding the lamb feed by stomach tube. Move to warming box until it reaches 101 degrees F. Return to mother.

For lambs with temperatures lower than 99 degrees F: More than five hours old, unable to hold up head or swallow. Give IP injection of glucose. Move to warming box. Collect milk or colostrum from the mother if possible to use in feeding the lamb. Check temperature every 20 minutes until it reaches 99 degrees F. Feed by stomach tube. Return to warming box until it reaches 101 degrees F. Return to mother

More than five hours old, able to hold head up and swallow: Move to warming box. Collect milk or

Continued on page 16 colostrum from the mother if possible to use in feeding the lamb. Check temperature every 20 minutes until it reaches 99 degrees F. Feed by stomach tube. Return to warming box until it reaches 101 degrees F. Return to mother

Less than five hours old, able to hold up head and swallow: Move to warming box. Collect colostrum from the mother if possible to use in feeding the lamb. Check temperature every 20 minutes until it reaches 99 degrees F. Feed by stomach tube. Return to warming box until it reaches 101 degrees F. Return to mother

Step 3. Follow up: If the lamb remains weak, it may need to be kept in draft-free, gently heated environment and fed by stomach tube regularly until it is strong enough to return to its mother. If at all possible, use milk or colostrum from the lamb’s own mother for all feedings, as this will increase the likelihood that the lamb will be accepted when returned to her.

Keep the ewe penned up with her lambs in a lambing jug or other easily monitored area where other ewes won’t interfere with bonding, and the chilled lamb will have as few distractions as possible. Watch the lambs for signs of starvation or dehydration until they’re solid and ready to rejoin the flock.

Step 4. Find the cause: Hypothermia and starvation cause a great deal of death loss and their treatment greatly increases labor requirements at lambing time. Shepherds should set a goal both for economic and animal welfare reasons to reduce hypothermia and starvation as much as possible. Each case should be noted in the lambing records of the dam, and the shepherd should attempt to pin down the cause of each case. After the crush of lambing is over, these records can be reviewed to look for patterns that might suggest management changes or culling of individual ewes.

Well-fed and -conditioned ewes can deliver and keep lambs fed and warm under fairly extreme temperatures, provided that they sheltered from wind, drafts, and moisture. Temperature alone should not cause hypothermia-starvation in shed lambed ewes unless the air temperature is below 0 degrees F.

Some management-related causes of hypothermia-starvation in shed-lambed ewes would include:

— poor maternal nutrition in early gestation when placental development takes place, leading to low birth weights and low milk production.

— poor maternal nutrition in late gestation, reducing fetal development and resulting in low birth weight and weakness in newborn lambs

— inadequate bedding; ewes lambing on wet or frozen pen floors

— drafts at floor level

— overcrowding of ewes leading to mismothering, grannying, or lost and wandering lambs.

— inadequate pen construction allowing lambs to wander away from their mothers.

Some disease-related causes of hypothermiastarvation would include:

— Ovine progressive pneumonia, which can cause reduced (or absent) colostrum.

— Any of the several abortion diseases, leading to weak newborn lambs.

— Mastitis, causing the ewe to refuse to allow the lambs to suckle, or past mastitis causing one or both sides of the bag to fail completely or partially.

If causes related to management and disease are ruled out, the most common cause of hypothermia and starvation in lambs is maternal inattention. Good mothering ability includes the skill of keeping track of your lambs and not allowing them to starve. In some rare cases, teat size and placement on the ewe can also be a factor. Be particularly attentive for ewes with excessively large, low, or high teats. Sometimes there can be plenty of milk that the lambs simply can’t get to.

Each operation needs to review its death loss totals and determine where it can improve, as death loss is one of the largest drags on profitability in most sheep operations. The overall goal should be to reduce death loss to the lowest practical point, and it makes sense to start with keeping newborn lambs alive and kicking.

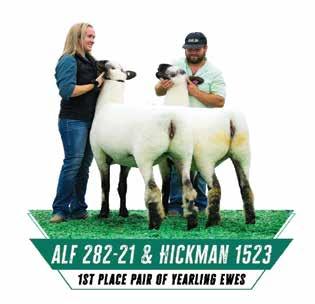

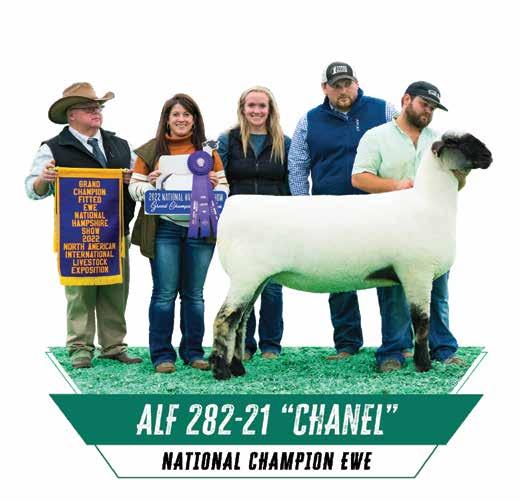

JANESVILLE, WI · JOHN: 608.449.0707

ALFHAMPSHIRES@GMAIL.COM