14 minute read

THE GREAT CHICAGO FIRE OCTOBER 1871

REMEMBERING ONE OF THE WORLD’S MOST NOTORIOUS INFERNOS

Advertisement

blocked by the James Dalton house. Regan testified that he heard music as he passed the McLaughlin house, where a party had been going on, on his way to help with the fire. This also didn’t match up with other testimony given by Mrs. McLaughlin who said that the fire had started after the music stopped.

Locals had suggested a theory that the two men were in the barn, where they had been hundreds of times and began to argue. In the midst of a fight they perhaps accidentally knocked Mr. Sullivan’s pipe from his hand, leaving it on the ground and sparking the initial flames.

Another theory surrounding the cause of the fire is that it may have been ignited by a fragment of a rogue comet that touched off upstate Wisconsin and Michigan on the same night. Scientists have speculated that fragments from Biela’s Comet could have ignited the Great Fire in Chicago but it has often been rejected. Chicago at the time was a place where the manufacturing East met the agricultural West of the U.S. This was also a time when the nation was beginning to flex its financial muscles on the international stage. There was an ever-increasing influx of people, money, goods, and information. There was the lake front and the branches of the Chicago River, which split the city into north, south, and west; each sector buzzing with commercial activity. Ten railroads converged on Chicago. The city was linked by rail coast to coast. Seventeen grain elevators had a total capacity of about 12 million bushels. The city had averaged about two fires a day during the previous year, including 20 in the previous week. The largest of those had occurred on the Saturday night, on the eve of the “Great Fire.”

After the fire began at the O’Leary’s it surged straight to the centre of town, aided by gusting winds. The blaze then unexpectedly jumped the South Branch of the Chicago River around midnight. Splitting in two yet again, the fire consumed Conley’s Patch, a shanty town of Irish immigrants. These were tightly packed wooden structures that offered no resistance to the blaze. By 1:30 the raging fire had made its way to the city’s courthouse tower. City officials released the prisoners’ moments before the great bell came crashing through the ceiling of the basement of the building.

In the south side of the city, the offices of the Chicago Tribune, whose editors throughout the summer had railed against lax fire safety standards, were completely destroyed. The fire was now so massive and widespread that even the ground was in flames. The streets and bridges were all made of wood which provided sufficient fuel for the inferno. The river was also vulnerable, as several vessels on the water and grease that had been dumped along the banks of the river also ignited. The runaway inferno was now showing signs of what fire fighters call a “convection effect.” This is where a fire has the ability produce a concentrated updraft allowing it to move forward on its own accord without help from any wind. Air from all directions was getting sucked into the centre of the flame. This generated a whirlwind effect that carried flaming debris high into the sky.

The flaming debris landed onto the city waterworks, destroying the structure and effectively shutting down any firefighting efforts. As the fire marched relentlessly north, another phenomenon known as spontaneous combustion resulted in buildings bursting into flames without coming into contact with the main body of the fire. In the North Division of the city, tens of thousands of ethnic Scandinavians and Germans had more time to escape than those in Conley’s Patch, yet nearly all suffered the same fate — the loss of whatever dwelling in which they had resided. Miraculously, only the mansion of real estate millionaire Mahlon D. Ogden was spared from the flames, saved by a shift in the wind. Eventually the fire reached the edge of the city with only prairie grass and dry sod to feed the flames, and expired on its own. The burned-out, bedraggled, and newly homeless flocked together in disoriented groups on open stretches of prairie west and northwest of town; in the South Division, refugees huddled along Lake Michigan, in the North Division, they hunkered down at the south end of Lincoln Park and along “the Sands,” a scrap of lake shore just north of the river.

People who previously had little reason to speak to each other were shepherded together in one group. As one historian put it, “One could find Mr. McCormick, the millionaire of the reaper trade, and other north-side nabobs, herding promiscuously with the humblest labourer, the lowest vagabond, and the meanest harlot.”

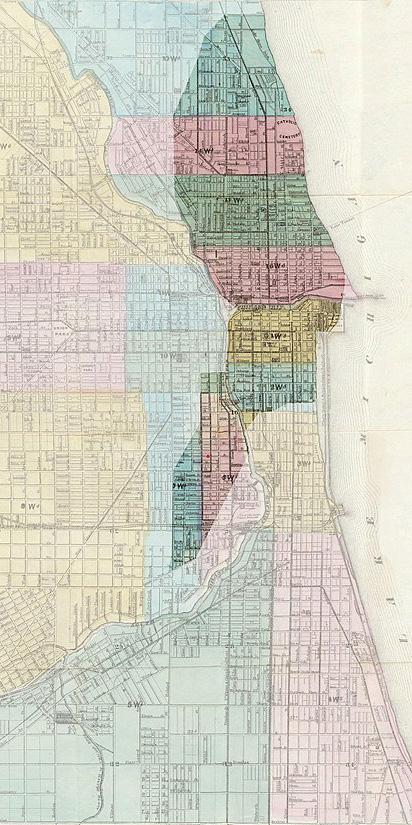

The aptly called “Burnt District,” a map of which appeared in virtually every printed account of the fire, comprised an area four miles long and an average of three-quarters of a mile wide — more than two thousand acres — including more than 28 miles of streets, 120 miles of footpaths, and at least 2,000 lamp posts.

Gone, too, were countless trees, shrubs, and flowering plants in “the Garden City of the West.” Approximately 18,000 buildings and about a third of the valuation of the entire city went up in flames. Even though half of that amount was insured, several company failures cut the actual payments in half.

Those structures and businesses left standing were located on the west or south sides of the Burnt District. They included most of the heavy industries, including the stockyards. The downtown railroad depots were totalled, but not the far more critical rail lines themselves. What the fire could not touch was one of Chicago’s most important assets, its location. It made the city more accessible to resources and markets throughout the nation and the world at a time when the United States was assuming a role in world leadership in industrial enterprise.

Because of Chicago’s pre-fire economic momentum and commercial ties and the unique geographic situation, the city was in a good condition to be able to rebuild.

One thing the Great Fire hadn’t taken from the people of Chicago was their grit and determination to rebound from the tragedy. The city would in time become bigger, better and ultimately wiser. The great fire had brought the best out of the citizens of Chicago.. Joseph Medill, publisher of the Chicago Tribune, put out a special edition trumpeting, “Chicago will rise from the ashes!” Potter Palmer, whose new hotel and 32 other holdings were destroyed in the fire, set out immediately to raise capital for reconstruction. Jonathan Scammon broke ground on a new, fully pre-rented office building only four days after the fire. The confidence and enthusiasm of those men and others rang up and down the social ladder, calling Chicagoans to the challenge.

City officials, in makeshift offices in the First Congressional Church on the city’s west side, set the price on bread, forbade wagon drivers from charging more than what was normal, and limited saloon hours, in order to keep looting and price-gouging to a minimum. They also banned smoking. Even before the fire burnt itself out, plans were being made to remake the city. Within days, even as the rubble was being removed, enterprising small businesses erected sheds and stands. Business traffic began to move again. Within six weeks, more than 200 stone and brick buildings had been started in the South Division alone.

By 1872, $50 million had been pumped into construction. In 1873, amid a national recession, Chicago proudly hosted the Inter-State Industrial Exposition, which promoted the city and the Northwest (of that era). By 1885, America had its first skyscraper, the nine-story high Home Insurance Building. Over the next two decades, hundreds of millions of dollars would pour into Chicago. By the end of the 19th century, the city was well on its way to recovery.

In 1986, the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in the Ukraine resulted in the most severe demonstration of what can happen when nuclear power goes wrong. In the aftermath of the devastating explosion, thousands of firefighters, soldiers and other emergency crews battled the imminent threat of a second explosion, which would have rendered Europe uninhabitable. Facing impossible odds and fatal radiation doses they succeeded. They were known as the 'Liquidators.'

By Antonia Musgrave.

Lyudmilla Ignatenko was the wife of firefighter Vasily Ignatenko, who died from radiation poisoning 14 days after he courageously fought the fires at Chernobyl in 1986. She talks about the events that followed the explosion, and how it took her husbands life. As she nursed her husbands in a special radiation hospital days after the event she remembered the day before; “There’s a photo of us all in the building. Our husbands are so handsome! And happy! It was the last day of that life. We were all so happy!” Vasily was exposed to fatal amounts of radiation when fighting the fires at Chernobyl and as a result spent 14 days waiting for the poison to consume him until he was finally released. Lyudmilla describes how his body fell apart from the radiation in his blood; “The last two days in the hospital -- I’d lift his arm, and meanwhile the bone is shaking, just sort of dangling, the body has gone away from it. Pieces of his lungs, of his liver, were coming out of his mouth. He was choking on his internal organs. I’d wrap my hand in a

The Liquidators

EUROPE'S FORGOTTEN HEROES

“THE ACCIDENT WAS PLAYED DOWN AT THE TIME BY THE SOVIET AUTHORITIES AND IT WAS ONLY WITH THE FALL OF THE USSR, AS NEW DOCUMENTS EMERGED, THAT THE TRUTH OF THE DEVASTATING INCIDENT HAS BEEN REALISED. THANKS TO THE FIREFIGHTERS AND EMERGENCY WORKERS, THEN KNOWN AS THE ‘LIQUIDATORS’, NOW KNOWN NOW AS THE ‘FORGOTTEN HEROES’, CHERNOBYL NARROWLY AVOIDED A SECOND EXPLOSION.” bandage and put it in his mouth, take out all that stuff. It’s impossible to talk about. It’s impossible to write about. And even to live through. It was all mine.”

Her shocking story is just one of many of the Chernobyl survivors. Chernobyl was the greatest disaster in the history of nuclear power, claiming the lives of hundreds at the time of the explosion in 1986, and thousands to this day. The power station that was in Chernobyl, suffered a problem in a reactor that led to an explosion releasing deadly radiation throughout the area, leading to levels of contamination throughout Europe. The accident was played down at the time by the Soviet authorities and it was only with the fall of the USSR, as new documents emerged, that the truth of the devastating incident has

Thanks to the firefighters and emergency workers, then known as the ‘Liquidators’, now known now as the ‘forgotten heroes’, Chernobyl narrowly avoided a second explosion which would have been 10 times more powerful than Hiroshima, it would have wiped out half of Europe.

On the 26th of April 1986 at 1:23am a routine test began on reactor 4 in the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, during the procedure the reactor plummeted to an unexpected low and unstable level of activity. The reactor should have been shut down, however operators chose to continue the test, causing a catastrophic explosion in the reactor building. The blast caused a fire that burned 1,000 meters high, releasing radioactive vapors that turned the sky orange and red. Machine operator Youri Korneev, described the scene as ‘beautiful’, adding that the colors were like ‘blood against the blackness of the sky.’ The first firefighters on the scene battled the blaze without adequate protective clothing and were exposed to lethal doses of radiation. Some of the firefighters climbed into the machine hall to fight the fires there. All were extinguished, except for the graphite fire deep inside the reactor. Despite fighting the blaze with tonnes of water, it would not die. Two firefighters died that night, with 28 following over the next few months, due to fatal radiation doses. They were the first of thousands that would die as a result of Chernobyl. With the graphite fire still burning and releasing copious amounts of destructive radiation into the atmosphere, emergency workers attempted to fight it by suffocating it under numerous sandbags. This helped initially by locking the fire inside the reactor, but lead to the threat of a second explosion that would have left almost all of Europe uninhabitable. Following the explosion the Ukrainian authorities made little effort to inform the public of the accident, or more importantly the risk of radiation. Leaving the people of Pripyat, just 3km from the plant, exposed to the deadly radioactive vapors that were 15,000 times higher than usual. The towns people were left to consume the fumes for three days. Four days of exposure would have been fatal. People complained of a metallic taste in the mouth, unaware of the explosion and the risk to their lives. The authorities have claimed that they were trying to avoid panic at the time by withholding information.

On the third day 1,000 buses were sent to Pripyat to evacuate the town, which to this day is a ghost town, completely deserted and uninhabitable due to the radiation levels. From April 26-27 the cloud that formed over the explosion traveled north over Russia and released radioactive rain on Stockholm. Within the next few weeks the cloud traveled around Europe to Poland, Czech Republic, Germany, Greece, the Netherlands, France and Great Britain raining along the way contaminating crops and pastures. Despite the explosion, the radiation cloud traveling through Europe and the evacuation of Pripyat, the Soviet Union remained silent. Ukraine refused to acknowledge the situation, encouraging people to celebrate May Day festivities in highly radioactive areas. Disturbingly all footage of these festivities have disappeared from the Ukraine National Archives. The worst was yet to come.

The ‘clean up’ of Chernobyl began by employing thousands of emergency workers, firefighters, soldiers, doctors and nurses to become part of the ‘liquidation’ of the area. The radioactive dust that covered Pripyat and the surrounding areas had to be cleaned up, earth was bulldozed into ditches and covered with cement. Similarly houses had to be knocked down and buried, and cats and dogs had to be killed. During this time, 10 days after the explosion, authorities discovered that 195 tons of nuclear fuel was still burning, creating an incredible heat that was gradually melting the sand creating the threat of a second explosion. If the radioactive magma made contact with the water, used originally to extinguish the fire, it would cause an explosion that would raze the city of Minsk, 320km away, and claim thousands of lives in a matter of hours. The military sent in firefighters, now regarded as national heroes, to drain the water from under the reactor. The firefighters were exposed to deadly amounts of radioactivity, adding to the everincreasing death toll.

With the threat of a second explosion still looming, it was decided that it was necessary to go under the plant through the pipes to create a room that would protect the radioactive magma from the water. For this the authorities drafted miners from a small town in rural Russia to create a tunnel under the plant. The surviving miners have described how the risk of the job was dramatically understated to them at the time. They were completely unaware of their exposure to radioactivity, therefore did little to protect themselves at the time. The tunnel would take just over a month to complete, giving the miners ample time to become seriously ill from the poison they were exposed to. 8,000 liquidators were employed in the ‘clean up’ process, and it is now thought that the job claimed 2,500 lives. Although, this statistic does not feature on any official documentation. After avoiding a second explosion, the focus then turned to the radioactive matter that covered the area. Remote controlled machines were used to clear the roof of the reactor so it could be buried inside a tomb of steel and cement. However, due to the high levels of radiation at this point, the robots went haywire and threw themselves off the reactor. Russian soldiers were then brought in to take over from the robots, gaining the name biorobots.

Each soldier made their own suit covered in lead to protect themselves from the radiation and took turns to shift the rubble and build the tomb. This was the most dangerous job in the most dangerous area. Bio-robots were sent on to the roof of the reactor to clear graphite and radioactive matter. The soldiers worked in shifts of 45 seconds, any longer would have been fatal. After their 45 second shift the soldiers would come down feeling drained and nauseous, some suffering nose bleeds. The soldiers received a ‘liquidator certificate’ and a bonus the equivalent of $100. However having paid the price, most of the biorobots are now dead or suffering greatly with ill health and/or disability. For those still alive, the war continues. Most are unable to work, due to the exposure at Chernobyl survivors aged 50 struggle like 70-year-olds. Due to Ukraine’s adverse economic situation, approximately 1,000 people have returned to the exclusion zone following the explosion and lived with unnaturally high levels of radiation.

It is now widely accepted that the Chernobyl accident has resulted in a massive increase in thyroid cancers in the three countries most affected. 680 cases of thyroid cancer have been recorded in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine. There was also an outbreak of the cancer in the south of France where the Chernobyl cloud had rained days after the explosion. Most disturbing though is the link Chernobyl has with child deformity. There has been a substantial increase, in affected areas, of children with birth defects. Causing speculation that it was caused through the pregnant women’s intake of radioactive crops that were contaminated by the disaster. From the day reactor 4 exploded to the present day, there has been dispute over the information given by the Ukrainian authorities regarding the levels of radiation and the death toll. At the time of the accident in 1986, the public was not informed of the radiation levels measured during the recovery work; the figures that were published were falsified. The firefighters, rescue workers and liquidators had not been made aware of the acute danger of the radiation they were being exposed to.

To this day it is still unknown how many the Chernobyl disaster has affected. According to the official 2002 Ukrainian statistics and subsequent projections based on them, 15,000 to 50,000 people are estimated to have died from the disaster. The suicide rate is also claimed to have risen drastically. Chernobyl is still a concern to the Ukrainian government even today. Since 1986, the ruptured reactor in unit 4 has been contained by a temporary sarcophagus. This isolates the destroyed reactor with a thick mantle of steel and concrete. The sarcophagus is designed to contain the reactor’s heat and radiation, because on the inside, not much has changed since the meltdown. Of the 190 tonnes of reactor core mass, an estimated 180 tonnes are still there, in the form of dust and ash. Despite the heroic efforts of the liquidators, that first sarcophagus was never meant to last and a long-term solution was still needed. Yet until the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the true situation at the site remained unclear. This became the technical basis from which the rest of the world would address the problem.

Unveiled in November 2016, Chernobyl’s new sarcophagus took two decades to make. Bigger than Wembley Stadium and taller than the Statue of Liberty, it will seal in the entire disaster site for 100 years.

The accident at Chernobyl has had a huge impact on the environment especially in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine. In addition, it has had a negative impact on the health of the hundreds of thousands of people involved in the clean-up and those who still live in heavily contaminated areas. Due to the long half life of many of the radionuclides released a huge area will remain contaminated for generations to come. It is important too, that we remember and acknowledge those who risked, and gave, their lives to prevent a second explosion and clean up the fallout and radioactive debris that the Chernobyl disaster left behind.