24 minute read

History had to take the flesh and form of a certain black man who was bold enough, wise enough and selfless enough to assume the awesome responsibility.

THE LAST OF THE GREAT SCHOOLMASTERS

By Lerone Bennett, Jr.

Advertisement

Before 500,000 could march on Washington D.C., before 30,000 could march from Selma, before there could be rebellion in Black America and renewal in the White Church, before SNCC could sit-in, before Stokely Carmichael could talk Black Power, before Martin Luther King, Jr., could dream, History had to take the flesh and form of a certain black man who was bold enough, wise enough and selfless enough to assume the awesome responsibility of preparing the ground for a harvest, the fruits of which they would probably never taste themselves.

OF THE HANDFUL OF MEN

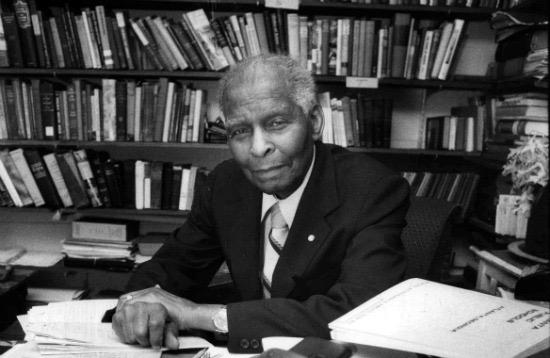

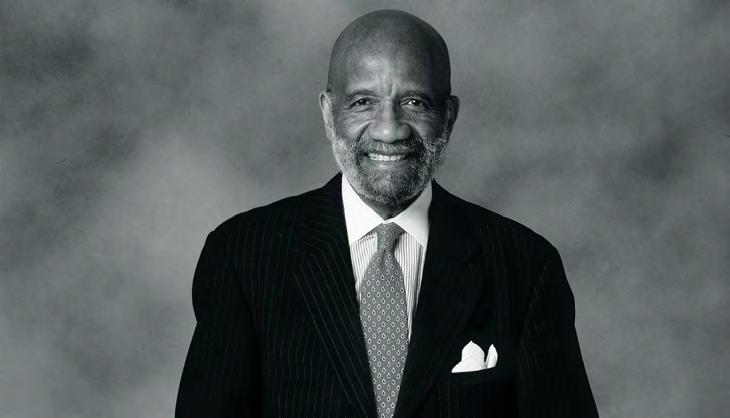

called by History to this delicate and dangerous task, none tilled more ground or harvested more bountiful crop than Benjamin Elijah Mays, a lean, beautifully black preacher-prophet who served as School Master of the Movement during a ministry of manhood that has spanned some 57 years, 27 of which were spent as president of Atlanta’s prestigious Morehouse College. During this period Mays, who is now 83 and president of the Atlanta Board of Education, helped to lay the foundation for the new world of Black and White Americas.

Master of a variety of roles (teacher, preacher, scholar, author, newspaper columnist, activist), Mays was enormously effective in the formative years of the Black Revolution in structures of power (executive committee of the World Council of Churches and International YMCA, president of the United Negro College Fund, vice-president and board member of the NAACP). In these different roles, he had a direct and pervasive influence on the Black Church, the White Church, the Black college, the White college, and the emerging freedom movement.

OF EQUAL AND PERHAPS GREATER IMPORTANCE WAS THE INFLUENCE THAT HE EXERTED ON EVENTS THROUGH GIFTED STUDENTS (MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., JULIAN BOND, MAYNARD JACKSON AND OTHERS) WHO FIRST CAUGHT THE FLAME OF FREEDOM AND REASON WHILE ORBITING IN THE SPHERE OF MAY’S INFLUENCE.

To these students and others who felt his influence indirectly, Mays was successful, above all else, in projecting an image of engaged, involved manhood. And this energizing image, imperious and demanding, spread in ever-widening circles, making disciples of Black men who never crossed Mays’s path, making debtors of White men who never heard his name. Samuel Dubois Cook, a former Mays student and the president of Dillard University, says “Mays’s genius was as an inspirer and motivator as well as a transformer of young men. With the possible exception of [Robert] Hutchins [University of Chicago], he had no peer among his contemporaries as a schoolmaster. I rank him with America’s greatest educators, with William Ramsey Harper of the University of Chicago, Nicholas Murray Butler of Columbia, and Charles W. Eliot of Harvard.”

I AM CONVINCED THAT IT WOULD BE A GREAT WASTE OF TIME TO SHOW A PEOPLE OF INTIMIDATED SLAVES A DIFFERENT MANNER OF SPEAKING, A DIFFERENT MANNER OF GESTICULATING; BUT PERHAPS IT WOULD BE WORTHWHILE TO SHOW THEM A DIFFERENT WAY OF LIVING. NO WORD AND NO GESTURE CAN BE MORE PERSUASIVE THAN THE LIFE, AND, IF NECESSARY, THE DEATH, OF A MAN WHO STRIVES TO BE FREE, LOYAL, JUST, SINCERE, DISINTERESTED; A MAN WHO SHOWS WHAT A MAN CAN BE. --- IGNAZIO SILONE

America, the world of daily chapel and moral exhortations and unlimited horizons and hopes, disappeared with the electronic age. But Cook and others believe that Mays legacy is one of the great possessions of Black people and America. And he believes with others, including Hugh Gloster, Mays’s successor at Morehouse, that the Mays legacy is critical at this juncture in America education and American life.

Far in Advance of his time, a rational man in an irrational age, a Christian in a pre-Christian country, a tough black stone in a raging white fire, Mays sounded the preliminary chords of our era; and it is impossible to understand our era or the warning chords pointing to the future without some understanding of what he and the vanguard he represented dreamed, hoped and did.

Long before it was respectable or fashionable, Mays was calling the Christian Church to repentance and to the Cross.

When Mays came on the scene, the great hammers of the Black tradition—the Black Church and the Black School— had lost much of their force and relevance. Many schools and many churches had become accommodating and accommodative instruments of the status quo. By helping to renew the mission of these two vital institutions, Mays played a vital role in redirecting the historical wave of today.

BACK IN THE 20’S, LONG BEFORE IT WAS

SAFE, he was preaching, teaching and acting out the allegedly modern role of the New Negro.

LONG BEFORE BERKELEY, long before the crisis on American college campuses, he was pointing to the need for educational reforms and giving substance to his words by integrating Morehouse students into the decision-making apparatus of the College. Mays not only anticipated our era; he also risked place and position in unrelenting efforts to push major institutions into the modern world. One observes with interest that he organized his life around the Black Church and the Black School, the

two centers of resistance around which the Black man’s will to survive was structured. The Black Church in particular was the embodiment of the Black man’s will to see and be, the expression, one might almost say, of his belief that his suffering had a meaning and would have an issue. Benjamin Mays came out of that great tradition and he gave new dimensions to the tradition. In him, the Black religious impulse became conscious from the inside. Through him and in him, Black idealism reached new heights of vision and expression. Perceiving the hardening of the arteries of the Black Church and the increasing secularization of the DR. MAYS WITH/AT _____ urbanized Black masses, Mays sounded a prophetic warning in his classic studies, The Negro’s God (1938) and The Negro’s Church (with J.W. Nicholson in 1933). Many Black ministers, he wrote, were poorly trained, and many Black churches encouraged socially irrelevant patterns of escape. As dean of the School of Religion at Howard University (1934-1940) and as president of Morehouse College (1940-1967), and as co-founder of the Interdenominational Theological Center, Mays was centrally important in helping to correct some of these deficiencies. Martin Luther King, Jr., his most celebrated student, and other Black ministers have said that Mays was

the major influence on their lives. King, for example, had decided not to go into the ministry, which he believed was irrelevant and irrational. But he changed his mind after sitting for a few seasons at Mays’s feet. Mays’s sermons stimulated him, intellectually and spiritually. In Mays, King saw his ideal of what he wanted “a real minister to be.”

Mays also sowed seeds of renewal in the White church. As a speaker and preacher before thousands of influential White groups and as a high official of the Federal Council of Churches and the World Council of Churches, he hammered away at the sins of the Church. Never one to bite his tongue or to gild the truth with polysyllabic placebos, he told the American Baptist Convention in 1951 that the “home Christian church is the most highly segregated institution in the United States.”

IT WAS DURING THIS PERIOD THAT MAYS MADE, FOR PERHAPS THE FIRST TIME, THE NOW-FAMOUS STATEMENT THE “ELEVEN O’CLOCK ON SUNDAY MORNING IS THE MOST SEGREGATED HOUR IN AMERICA.” (THE STATEMENT, HE SAYS, IS STILL TRUE.)

Of like tone and texture was his electrifying address to the second General Assembly of the World Council of Churches in Evanston, Ill., in 1954. “Anyone,” he said, “who seeks shelter in the Bible for his defense of racial segregation in the church is living in a glass house which is neither rock-proof nor bullet-proof.”

No less instructive, and no less important, was Mays’s role in refurbishing the role of the Black college president. This has always been a difficult role, and it was even more difficult in the ‘30s and ‘40s, when Black college presidents had to satisfy conservative White public officials and philanthropists and restless and, yes, confused Black students. Finding themselves in an untenable position, in the crossfire of conservative White patrons and increasingly militant students, the best of the conservative college presidents offered themselves as willing sacrifices, making conscious efforts to educate men and women who graduated despising them. The worst beIt is a measure of Mays’s greatness that he entirely transcended these categories. Morehouse students never thought of him in traditional terms because he was not a traditional Black college president. When the NAACP was America’s SNCC, Mays was a conspicuously active member. And when the interests of the White power structure clashed with the interests of Black people, he was found on the side of the mothers and fathers of his students. In the ‘40s, when all or almost all public doors in Atlanta were closed to Paul Robeson, he opened the doors of Sale Hall Chapel and gave Robeson an honorary degree. In the ‘60s, when the sitin controversy sent most college presidents scurrying for cover, Mays was one of the courageous few who said the students were right and deserved the support of their elders.

Against the traditional view of Black education as “accommodation under protest,” Mays pressed a new conception of education as the liberation of power through the mastery of the accumulated lore of the ages. He conceived education broadly as an instrument of social and personal renewal, and he anticipated Paulo Freire’s conception of education as “the practice of freedom.” What Martin Luther King, Jr. said about Morehouse was echoed by almost all of his contemporaries. “There was a freer atmosphere at Morehouse,” King said, “and it was there that I had my frank first discussions on race. The professors were not caught up in the clutches of state funds and could teach what they wanted with academic freedom. They encouraged us in a positive quest for solutions to racial ills and for the first time in my life, I realized that nobody was afraid.” (Emphasis supplied)

As an educator, Mays addressed himself to the major problems of oppression—manhood. He did not intend, he said, to make lawyers or doctors or teachers – he intended to make men. And he intended to make them the hard way. “He who starts behind in the race of life,” he used to say, time and time again, “must run faster or forever remain behind.”

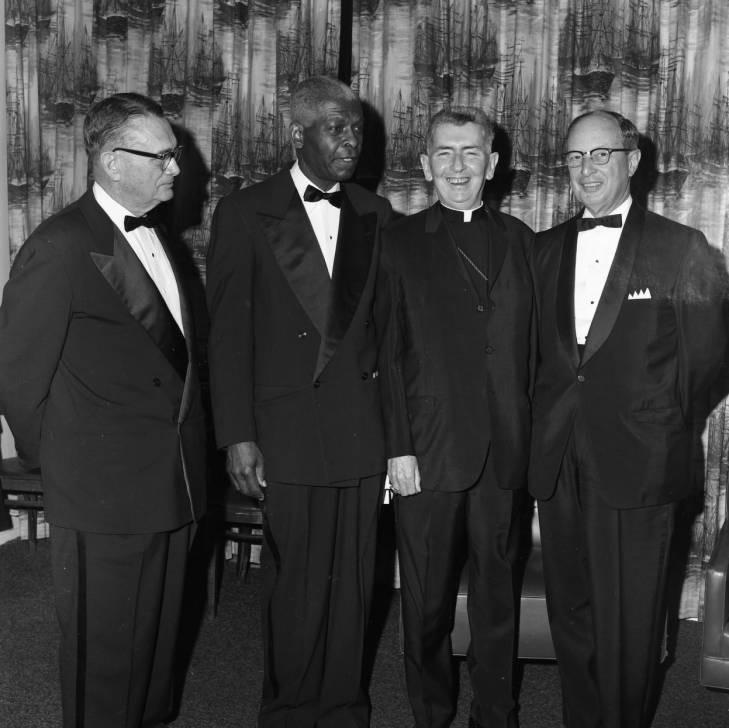

DR. MAYS WITH DR. JONES1

IT MUST BE BORNE IN MIND THAT THE TRAGEDY OF LIFE DOESN’T LIE IN NOT REACHING YOUR GOAL. THE TRAGEDY LIES IN HAVING NO GOAL TO REACH. IT ISN’T A CALAMITY TO DIE WITH DREAMS UNFULFILLED, BUT IT IS A CALAMITY NOT TO DREAM. IT IS NOT A DISASTER TO BE UNABLE TO CAPTURE YOUR IDEAL, BUT IT IS A DISASTER TO HAVE NO IDEAL TO CAPTURE. IT IS NOT A DISGRACE NOT TO REACH THE STARS, BUT IT IS A DISGRACE TO HAVE NO STARS TO REACH FOR. NOT FAILURE, BUT LOW AIM IS SIN.

-BENJAMIN E. MAYS

A MAKER of history, Benjamin Mays embodies in the flesh a great part of the history of Black people. He was two when Plessy v. Ferguson pushed Blacks back towards slavery, fifteen when the NAACP was founded, twenty-two when Booker T. Washington died, sixty-six when the Supreme Court reversed Plessy and opened the age of desegregation.

To understand Mays, one must understand these historical markers and how they intersected with his personal history. Mays, for example, was 19 before he had the privilege of attending school for a full year. He was 22 when he graduated from high school, 46 when he became the president of Morehouse College, 52 when he was permitted to vote for the first time, 76 when he became the first Black president of the Atlanta Board of Education.

To understand Mays, one must see him against the background of these events. One must see him, above all else, against the distant backdrop of South Carolina, where he was born near the town of Ninety-Six on August 1, 1894, the eighth child of two former slaves, Hezekiah Mays, a poor sharecropper, and his wife Louvenia. In that year in South Carolina, there were two Black representatives in the South Carolina legislature, and a Black man, George Washington Murray, represented South Carolina in the U.S. Congress. These men represented the last dying embers of the first Reconstruction; and soon after Mays drew his first breath, Blacks in South Carolina and elsewhere were driven from the polling booths and places of power.

In this environment, Mays came early to battle. One of his earliest memories is of a roving White mob looking for a Black to lynch, and he remember today that the environment was harsh and oppressive. “We never owned any land, never owned a home,” he says. “We never had much money, and were always in debt. It was poverty in a way, but we were never hungry. We always had enough to eat.”

God was real—and necessary—in the Mays household. Mrs. Mays was deeply religious and her son caught her spirit and relied heavenly on God and prayer. “I needed to rely on something,” he says now. in the fields, plowing, chopping cotton, spreading guano. Learning the alphabet from his oldest sister, he entered the one-room colored school with a head start on his contemporaries. This made a big impression on the teacher who told Hezekiah and Louvenia Mays that their son was destined for great things.

WHEN MAYS FOLLOWED UP THIS INITIAL TRIUMPH BY RECITING THE BEATITUDES ON A CHILDREN’S DAY PROGRAM AT MOUNT ZION CHURCH, THE ELDERS DECIDED THAT THE MAYS BOY WAS “MARKED” AND WAS “GOING TO BE SOMEBODY.” SO IMPASSIONED WAS HIS RECITAL ON THAT FAR AWAY SUNDAY THAT OLD MEN AND WOMEN LUMBERED TO THEIR FEET, SCREAMING AND SHOUTING.

Looking on this early triumph more than a half century later, Mays said: “I can still see them today, waving handkerchiefs, weeping, and shouting.”

Poor though he was, Mays managed by economies and odd jobs, including cleaning outhouses, to finish the high school program at South Carolina State. He attended Virginia Union where he decided that he had to test his mind against the best White minds of the day. He applied for admission to several big Eastern schools and was rejected on racial grounds. (One of the major universities later awarded him an honorary doctorate.) In 1917, he was admitted to Bates College in Maine. Waiting tables, tending furnaces and running on the road as a Pullman porter, he worked his way through Bates and later received M.A. and Ph.D. degrees at the University of Chicago. After pastoring a church in Atlanta and teaching mathematics and English

at Morehouse and South Carolina State, where he married Sadie Gray, Mays was appointed executive secretary of the Tampa (Florida) Urban League. The rising young leader-activist spent two years at this post before accepting a position as national student secretary of the YMCA. In 1934, he became dean of Howard University School of Religion.

As a Howard University dean and as a teacher and staff member of the interracial coalition movement, Mays was a leading member of the black vanguard which was charged with the historic mission of maintaining pressure on every level while preparing Black people – through teaching, preaching, organizing, clarifying, and defining – for a leap to a higher level of development. At that point, Black people did not have the means of going beyond passive, dignified protests, and the struggle had to be carried on by vanguards and individual acts of resistance. One hears, now and then, snide remarks about this vanguard from people who, lacking a sense of history, add insult to plagiarism. The bold and honest men of that generation did all that was possible with the material available, with the degree of consciousness attained by the masses, under existing circumstances. If we can see more and say more today, it is because we are standing on their shoulders. It required more than one bigger Thomas to say “No,” it require more than one Black to die on Southern busses, it required more than one Benjamin Mays to spread manure in the fields of South Carolina before a whole people could cast off the grave clothes of slavery and push their way to the center of the national stage. The point here is that Black people in American never ceased to struggle, never ceased to live in combat. The will to dignity of Blacks was maintained in the unbroken, though not always visible, line – in the struggle of isolated vanguards, in the unbroken spirit of the masses, in the seminal contributions of individual pathfinders like Benjamin Mays.

While Mays and the vanguards struggled, buying time and space, new powers fashioned themselves in the depth of the people and the arc of the world turned. In a perspectives article, published in 1946, Mays warned that the time of retribution was near. The “pressure from below,” he said, “will increase rather than diminish in the postwar years….Increasingly and more vigorously, [the colored races of the world] will oppose exploitation, segregation, and discrimination based on color and race.”

“IT WILL NOT BE SUFFICIENT FOR MOREHOUSE COLLEGE, FOR ANY COLLEGE, FOR THAT MATTER, TO PRODUCE CLEVER GRADUATES, MEN FLUENT IN SPEECH AND ABLE TO ARGUE THEIR WAY THROUGH; BUT RATHER HONEST MEN, MEN WHO CAN BE TRUSTED IN PUBLIC AND PRIVATE – MEN WHO ARE SENSITIVE TO THE WRITINGS, THE SUFFERINGS, AND THE INJUSTICES OF SOCIETY AND WHO ARE WILLING TO ACCEPT RESPONSIBILITY FOR CORRECTING THE ILLS.”

In 1940, on the eve of the new era, Benjamin E. Mays became president of Morehouse College. He was 46 years old. Although Mays did not know it at the time, Morehouse, which had an inviable record of producing preachers and teachers, and college presidents, was in danger of losing both its identity and independence. The story of how Mays saved Morehouse, of how he triumphed over internal and external forces and gave the school a new birth of purpose, is beyond the scope of this article; and the point of these observations is to emphasize the spirit of independence that motivated the man. “If Morehouse is not good enough for anybody,” he said at the beginning, “it’s not good enough for Negroes.”

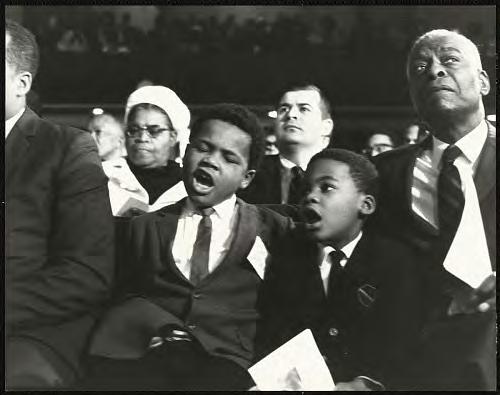

It was this spirit that endeared him to generations of students who entered Morehouse in the 1940s and 50s. Although he taught no classes, his spirit permeated the campus, and students made a point of catching his now-famous Tuesday morning Chapel talks. Week after week, Tuesday after Tuesday, for 27 years he preached engagement, responsibility and stewardship. Education, he said, was an obligation, not privilege. One was obliged, he said, to put ones theoretical knowledge at the disposal of people.

In this effort, the man Morehouse students called “Buck Benny” was engaged in total war against a system of ideas and values that had wormed its way into the neurons of his students and did not cease to destroy them, even while they slept. Mays wanted to “invent souls,” to use Cesaire’s beautiful phrase. He wanted to root out the weaknesses

and evasions which were the heritage of three hundred years of spiritual and material oppression. “If you are ignorant,” he told his students, “the world is going to cheat you. If you are weak, the world is going to kick you. If you are a coward, the world is going to keep you running.” Strong himself, Mays demanded strength from his students. He had developed early in life, he said, “a hard, maybe cruel, certainly an exacting and unrelenting philosophy,” which he applied to himself, to his students, and to all mankind. And the philosophy was simply this: “No person deserves to be congratulated unless he has done the best he could with the mental equipment he has under the existing circumstances.”

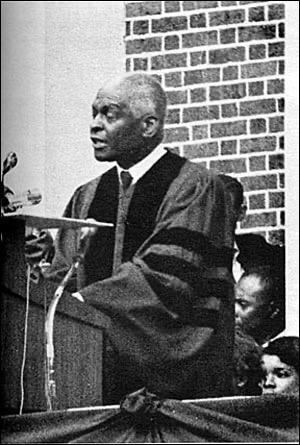

DELIVERING REV. DR. KING’S EULOGY

In concrete terms, Mays demanded a sense of mission. Every man, he said, is called of God to do his best in every situation and to make some unique and distinctive contribution, which only he can make. “Do whatever you do so well,” he used to say, “that no man living and no man yet unborn could do it better.”

At the same time and at first sight somewhat paradoxically, Mays said that knowledge was not enough. The Word was useful and even necessary, but greater than the Word was the deed. How many times, how many days, how many Tuesdays did he challenge his students with the stern hard words of John Drinkwater:

KNOWLEDGE WE ASK NOT— KNOWLEDGE THOU HAS LENT, BUT, LORD, THE WILL— THERE LIES OUR BITTER NEED, GIVE US TO BUILD ABOVE THE DEEP INTENT TO DEED, THE DEED.

Freedom is hard. Benjamin Mays understood that. There were no excuses and no hiding places in the world. The greatest crime was to give up; the greatest sin was to “aim low.” A witness for freedom, and a model of freedom. Mays created a climate of freedom which bore fruit. It is no accident that a disproportionately large number of his students went on to make their mark as college presidents, lawyers, doctors, teachers, Ph.D.’s and hell-raisers. It is no accident that a disproportionately large number of his students and disciples played prominent roles in the Freedom movement.

Throughout this period and on into the ‘70s, Mays remained on the battle line, preaching the acceptable year of the Lord. He was honored repeatedly in these years. Presidents Kennedy and Johnson appointed him to various commissions and delegations. In 1963, he was appointed by President Kennedy to the official U.S. Delegation to the funeral of Pope John. On another occasion, he was considered for the position of Ambassador to Israel. Press reports of the time said he declined the honor, but Mays says: “I was never offered the position. One could hardly turn down the President of the United States. When people came here to feel me out, I expressed a desire to stay in the field of education, and I never heard any more about it. Much later, when Sadie and I were going through a reception line at the White House, President Kennedy stopped me and announced:

DR. MAYS WITH PRESIDENT CARTER

Either through a misunderstanding or a higher understanding of fate, Mays remained at the helm of Morehouse until his retirement in in 1967 on the 100th anniversary of the institution. He was succeeded by Hugh Gloster, a creative Morehouse graduate, and was named president-emeritus. Two years later, he was elected to the Atlanta Board of Education. Since 1970, he has been president of the

Board and last October, at the age of 83, he was reelected to his third term. By all accounts, he has been an effective and influential leader of the Board. Richard Raymer, a White member of the Board, said that “during his leadership, the Board has dealt successfully with a number of explosive issues, including labor problems and desegregation. Under his leadership, the Board successfully negotiated settlements that have made Atlanta a better city to live in. There are five Blacks and four Whites on the board, but there has not been a single instance where the Board divided on racial lines. We’ve divided along sexual lines (there are five women and four men on the Board) but never on racial lines. This is a tribute to his leadership. He is the most widely respected citizen in Atlanta today. If you took a poll, he would come out on top. He is the kind of man we would like our kids to grow up to be.”

THE KIND OF WORK UNCLE BEN DOES IS NOT WHAT YOU WOULD CALL WORK, BECAUSE HE ENJOYS DOING IT AND IS SO USED TO IT THAT IT IS KIND OF RELAXATION FOR HIM. IT’S LIKE A LONG-DISTANCE RUNNER. THE FIRST ONE OR TWO MILES ARE HARD, BUT THE NEXT THREE HE JUST TAKES IN STRIDE.

--DWIGHT JEROME POWELL, NEPHEW

HE IS 83 NOW.

The friends of his 20s, the friends of his 40s, the friends of his 60s: almost all of them are dead and gone. The great and gracious Sadie Mays, the companion of his years, is gone, buried nine years ago in the middle of his first campaign for the Board of Education. People, principalities, institutions, laws have lived and died, but Benjamin Mays, the long distance runner, is still on the track and on the case, maintaining a schedule that would kill a man half his age, speaking three and four times a month, writing books and articles and newspaper columns, pursuing the high sharp exhilarating edge of what he likes call “the unattainable goal.” He rises early in his comfortable Southwest Atlanta home, and he goes to bed late. He is attended by a house keeper and is surrounded by in-laws and relatives, but there are few frills, few diversions in his life. Such a man, as can be imagined, is somewhat intimidating. And although he has a sense of humor and a proper appreciation of baseball averages and a glass of Bristol Cream Sherry, he is often invited out for evenings of fun and frivolity. One imagines that bothers him a little, but it doesn’t keep him from running the race he has decided to run. It is interesting to note, however, that he told a friend once that when he was retired from Morehouse he was going to buy a red convertible and drive down Auburn Avenue with the top down and his collar unbuttoned. He didn’t buy the red convertible, but he did change his wardrobe, buying a number of colorful sports coats.

The plaid coats and colorful ties are new, but the central thrust of the man’s life is old and unvarying. Work is still his passion.

“CHASING IDEAS, BUILDING AIR CASTLES, GRASPING AFTER THE MOON, REACHING FOR THE STARS [HIS WORK] “: THESE ARE HIS DIVERSIONS. TODAY, AS ALWAYS, HE BELIEVES, WITH KANT, THAT MORAL WORTH, NOT HAPPINESS, IS THE GOAL OF LIFE. “DIE YOUNG, DIE MIDDLE AGED, DIE OLD,” HE HAS SAID, “(BUT) REMEMBER THAT THE MOST USEFUL LIFE AND THE MOST ABUNDANT LIFE IS THE ONE IN WHICH ONE DREAMS DREAMS THAT WILL NEVER COMPLETELY COME TRUE, AND CHOOSES IDEAS THAT FOREVER BECKON BUT FOREVER ELUDE. TO SEEK A GOAL THAT IS WORTHY, SO ALLEMBRACING, SO ALL-CONSUMING, AND SO CHALLENGING THAT ONE CAN NEVER COMPLETELY OBTAIN IT, IS THE LIFE MAGNIFICENT; IT IS THE ONLY LIFE WORTH LIVING.”

This is the life—hard, demanding, magnificent—that Benjamin E. Mays has lived, and is living. And in the 83 year of that life, he looked back through the haze of the years and said that he was “satisfied but not complacent” about the changes he has witnessed in his days. “There is no doubt,” he said, “that the

Negro is a thousand times better off than he was at the turn of the century. There is no doubt that virtually every Black boy has a much better chance to get an education than I did…There is no doubt that we have made some progress in race relations, but you still have to keep your eyes on the struggle against racism in the world and the fact that what the Negro has gained he has gained through struggle, and through the courts, and through marching and boycotting.” Whet advice does he have for the young? His only advice is “the challenge that I accept for myself, to keep tiptoeing and never accept mediocrity as a goal.”

Originally Published in Ebony Magazine: December 1977

1. Two Presidents. Left to right: Benjamin Elijah Mays (1894-1984), president of Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia from 1940 to 1967; and Dr. David Dallas Jones (1887-1956) president of Bennett College from 1926 to 1955 in Greensboro, North Carolina, USA, on the Bennett College campus, circa 1954. Caption: “Mr. Mayes [sic]-Pres. of Morehouse, Pres. Jones.” 2. Dr. Benjamin E. Mays gave the eulogy for Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. at an open-air service on the Morehouse campus. The memorial followed King’s funeral service at Ebenezer Baptist Church, where King had served as a co-pastor with his father. Lerone Bennett, Jr Morehouse ‘49

Zeta Phi Beta Sorority, Inc. Epsilon Psi Zeta Chapter of Greenwood, SC

The Epsilon Phi Zeta Chapter of Zeta Phi Beta Sorority, Inc. extends our warmest congratulation

to the GLEAMNS Dr. Benjamin E. Mays Historical Preservation Site on its 10th Anniversary.