3 minute read

Raising Hester Marsh

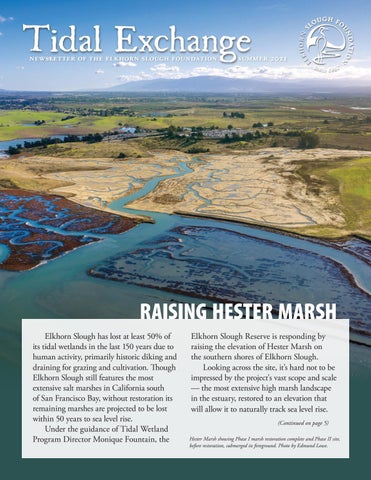

Hester Marsh, showing Phase I marsh restoration complete; Phase II site before restoration, submerged in foreground (Photo by Edmund Lowe Photography)

Elkhorn Slough has lost at least 50% of its tidal wetlands in the last 150 years due to human activity, primarily historic diking and draining for grazing and cultivation. Though Elkhorn Slough still features the most extensive salt marshes in California south of San Francisco Bay, without restoration its remaining marshes are projected to be lost within 50 years to sea level rise.

Under the guidance of Tidal Wetland Program Director Monique Fountain, the Elkhorn Slough Reserve is responding by raising the elevation of Hester Marsh on the southern shores of Elkhorn Slough.

Looking across the site, it’s hard not to be impressed by the project's vast scope and scale — the most extensive high marsh landscape in the estuary, restored to an elevation that will allow it to naturally track sea level rise.

The effort proceeded in three phases. In 2017, Phase I of the Hester Marsh Restoration Project broke ground. Heavy equipment moved 230,000 cubic yards of sediment to raise 60 acres of threatened marsh plain to an elevation that supports marsh resilience to rising sea levels. By the end of 2021, Phase II will have added an additional 130,000 cubic yards across an additional 29 acres of restored tidal marsh.

Lessons learned in previous phases of the the project helps researchers and project managers refine their approach to ongoing restoration.

Photo by ESF/ESNERR

Phase III — the final phase of the Hester Marsh Restoration, slated to begin in Fall 2021 — will add another 130,000 cubic yards across 29 acres, for a total of just under 120 acres of restored tidal marsh plain. Add to this roughly 13 acres of restored coastal grasslands and ecotone habitat along the marsh edges, and 15 acres of uplands used in constructing the wetlands, which we will restore with remaining funding, and the restoration area totals nearly 150 acres — an area equivalent to more than 110 regulation football fields. Even the comparisons defy the imagination.

Healthy coastal marshes are vital and invaluable — they protect shorelines and coastal infrastructure from erosion, buffer flooding and filter runoff, improve water quality, support wildlife above and below the tideline, and efficiently capture and sequester atmospheric carbon.

“We will restore the marsh by restoring the elevation and hydrology that allow marsh plants to thrive,” notes Reserve researcher Rikke Jeppesen. “By restoring hydrology, we mean re-excavating tidal channels based on historical photos, using computer mapping and calculations of channel volume and density to recreate healthy marsh habitat with proper drainage.” Ongoing monitoring has been key to measuring our success and guiding achievement of these objectives. Some monitoring follows time-tested methods, such as using transects and quadrats to survey plants, while some takes advantage of new technology, such as using Unoccupied Aerial Vehicles (UAVs or drones) to ensure construction meets key elevation targets, or to observe large-scale patterns of marsh re-vegetation.

Researchers are monitoring hydrology, plants, and wildlife at Hester Marsh using UAVs and traditional field methods, and applying theirfindings to inform ongoing restoration.

Photo by ESF/ESNERR

The common thread is that we use the lessons learned to inform the work ahead. As the Hester Marsh project embarks on each new phase of restoration, we make modifications based on findings from previous phases.

A lesson learned in Phase I construction, for example, refined how later channel edges were shaped. Firm and shallow edges, researchers found, were less susceptible to erosion than steeper edges — and provided ideal banks where harbor seals can haul out to rest on the marsh.

Firm, shallow edges provide areas for harbor seals to haul out and rest on the marsh banks.

Photo by Penny Palmer

From a broader perspective, we are learning how to repair past land use practices that changed the function of the estuary. Learning from the past informs restoration efforts in the present; we hope that future generations, in turn, will draw lessons from our practice.

The restoration of Hester Marsh isn’t complete, yet it already serves as a blueprint for how organizations can work collaboratively to successfully restore degraded coastal habitat. There is a long way to go yet in our collective effort to protect and restore these critical ecosystems, but we’re on the right track.