3 minute read

WELLSPRINGS OF HISTORY: Looking to the Past to Guide the Slough’s Future

Reserve Stewardship Coordinator Andrea Woolfolk is passionate about historical ecology — using historical documents to deepen our understanding of the land and how people have modified it, and to inform today’s strategies to protect the land for future generations. In the story that follows, Andrea offers a glimpse into the history of freshwater springs around the Elkhorn Slough, illustrating how knowing the past can help us plan for the future.

A spring fed pond on the Elkhorn Slough Foundation’s Renteria Ranch property

Freshwater springs are places where groundwater finds its way to the surface, often at the base of steep slopes, but sometimes in floodplains or even in tidal wetlands. Springs can be year-round or seasonal, showing up during the rainy season, and create conditions for wetland plants and wildlife like amphibians. They can be important water sources for streams, lakes, and wildlife, and are important to people, too.

In the past, freshwater springs were abundant in north Monterey county, and people thought they were important enough to map and write about.

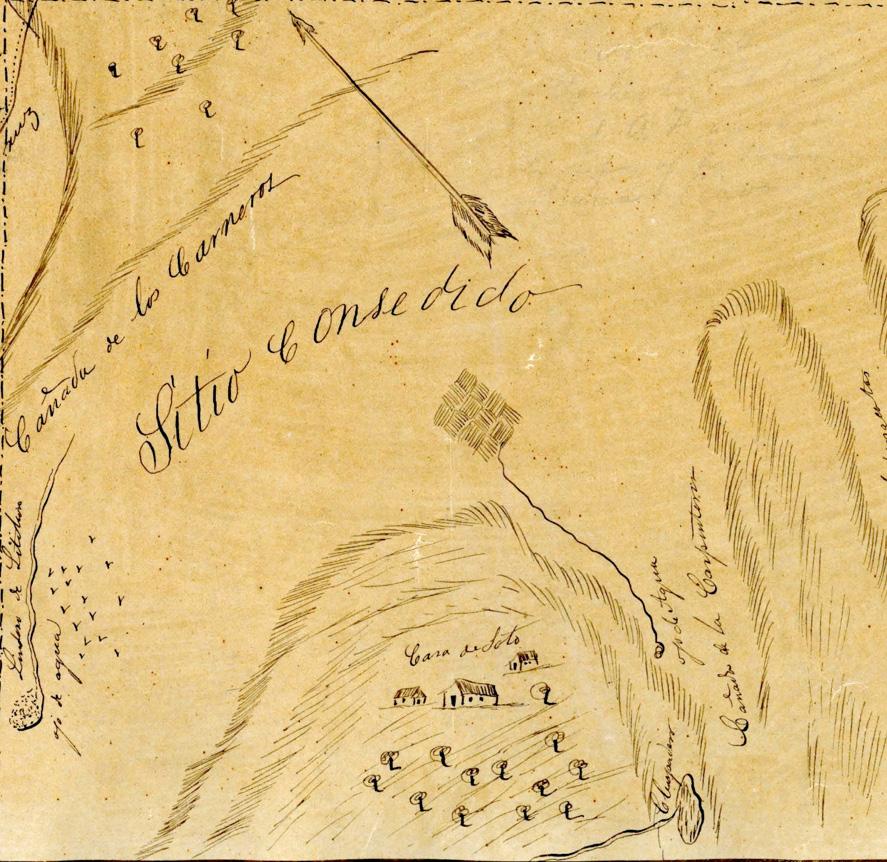

Early Spanish-speaking residents of Monterey County called springs “ojos de aqua” and they appeared in many of the earliest maps of the region. In 1836, Simeon Castro described his Bolsa Nueva rancho, one of the largest land grants in the Elkhorn Slough watershed, as including “a lake which lasts all year [the now reclaimed Merritt Lake] with other springs that dry up.”

An early map of Rancho Canada de la Carpenteria, near today’s Carneros Creek at Highway 101, shows three springs (“ojos de agua”) feeding short streams, one of which ends in a small farm field;

In 1869, a local newspaper described the uplands of the Elkhorn Slough as “well timbered and watered … having been abundantly provided with perennial Springs of the best water, gushing out from the hillsides, forming myriads of sparkling brooks and rivulets coursing their silvery threads through the valleys in every direction.”

So, what happened? Historical ecology offers some clues.

In 1925, the Soil Survey noted that local salt marshes included freshwater springs: “Tidal Marsh … this soil occupies areas of saline tidal flats and tidal marsh … small included areas of peaty soil affected by fresh water from springs or minor streams would become very valuable for agriculture if they were reclaimed. This soil occupies large saline marshland areas adjacent to Elkhorn and Moro Cojo Sloughs.”

Locals took the advice to reclaim marshy areas influenced by springs, and expanded on earlier efforts to pump groundwater, irrigating increasing numbers of acres for agriculture. Yet intensive pumping can lower groundwater levels and reduce or even eliminate springs, reducing local streamflow, and leaving some plants and animals without habitat.

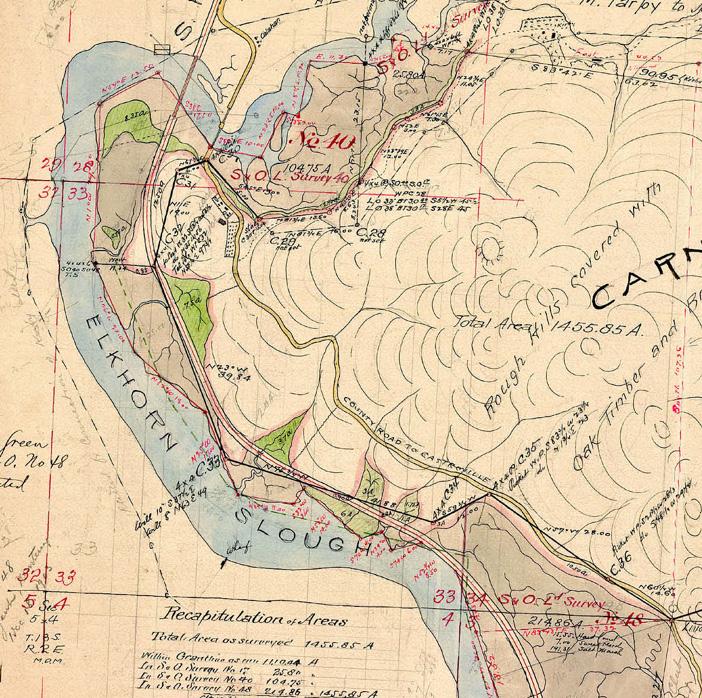

The green areas in this 1898 survey by A.T. Herrmann represent “sweet water marsh” fed by small freshwater streams or springs

In the 1980s, longtime Elkhorn Farm manager Bob Bowen told Mark Silberstein that on today’s Elkhorn Slough Reserve “there used to be springs … [there] was a flowing well and that was the supply of freshwater … it was an artesian well … [but then] the streams all dried up.”

Today, few of the springs mapped or described in historical documents survive. The Elkhorn Slough Foundation is working to restore some of the groundwater lost in the last 100 years. By implementing science-based land management practices, ESF has reduced water use on its 4,000 acres of protected lands by as much as 2,000 acre-feet (about 650 million gallons) of water annually — recharging local aquifers that feed these springs.

Woven Across Time

Interactive History Exhibit Opens at Elkhorn Slough Reserve this Fall

Slated to open at the Reserve Visitor Center this fall, "The Cultural Heritage & Historical Ecology of the Elkhorn Slough: Woven Across Time" is a new multimedia project incorporating interactive technology, audio recordings, and historical artifacts.

The new exhibit will weave stories from native peoples, early Spaniards, and current neighbors together with recorded ecological changes. It will feature recordings from our recent oral history project, with interviews of local farmers, families, and neighbors. These stories will complement journal entries, news articles, and other historical artifacts dating back to the 1700s.

We hope you will join us this fall to enjoy this new exhibit — as well as an Evenings at the Estuary presentation on historical ecology by Reserve Stewardship Coordinator Andrea Woolfolk — and deepen your understanding of the connections between natural and human communities.

This project was made possible thanks to the generous support of a grant from California Humanities.