3 minute read

Infrastructures of Invasion

from Eating Invasives

by Elaine Zmuda

What constitutes an invasion? The word has been applied widely to any arrival of unwanted people, animals, and plants. Invasion implies ill intent, harm, and destruction.

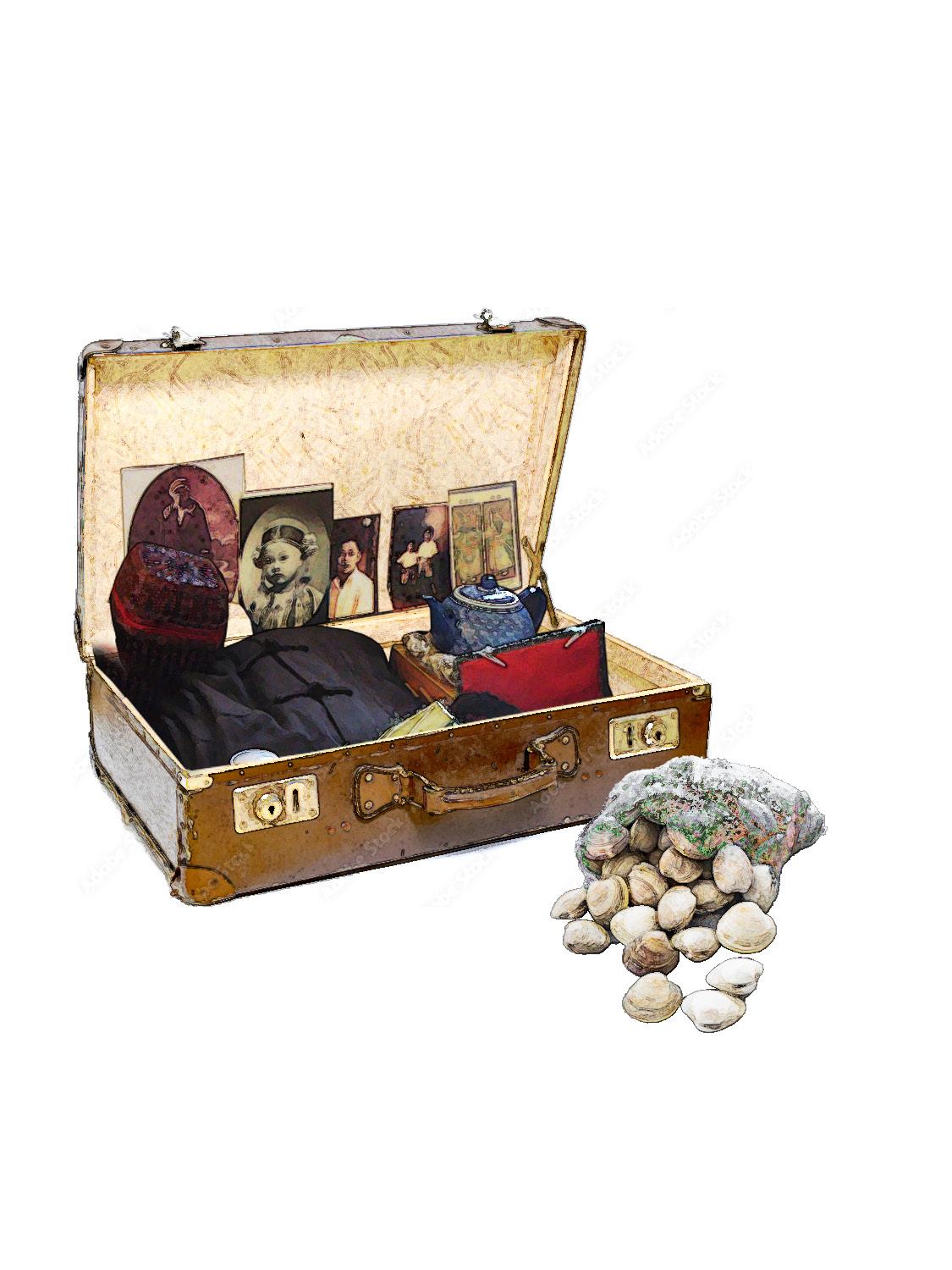

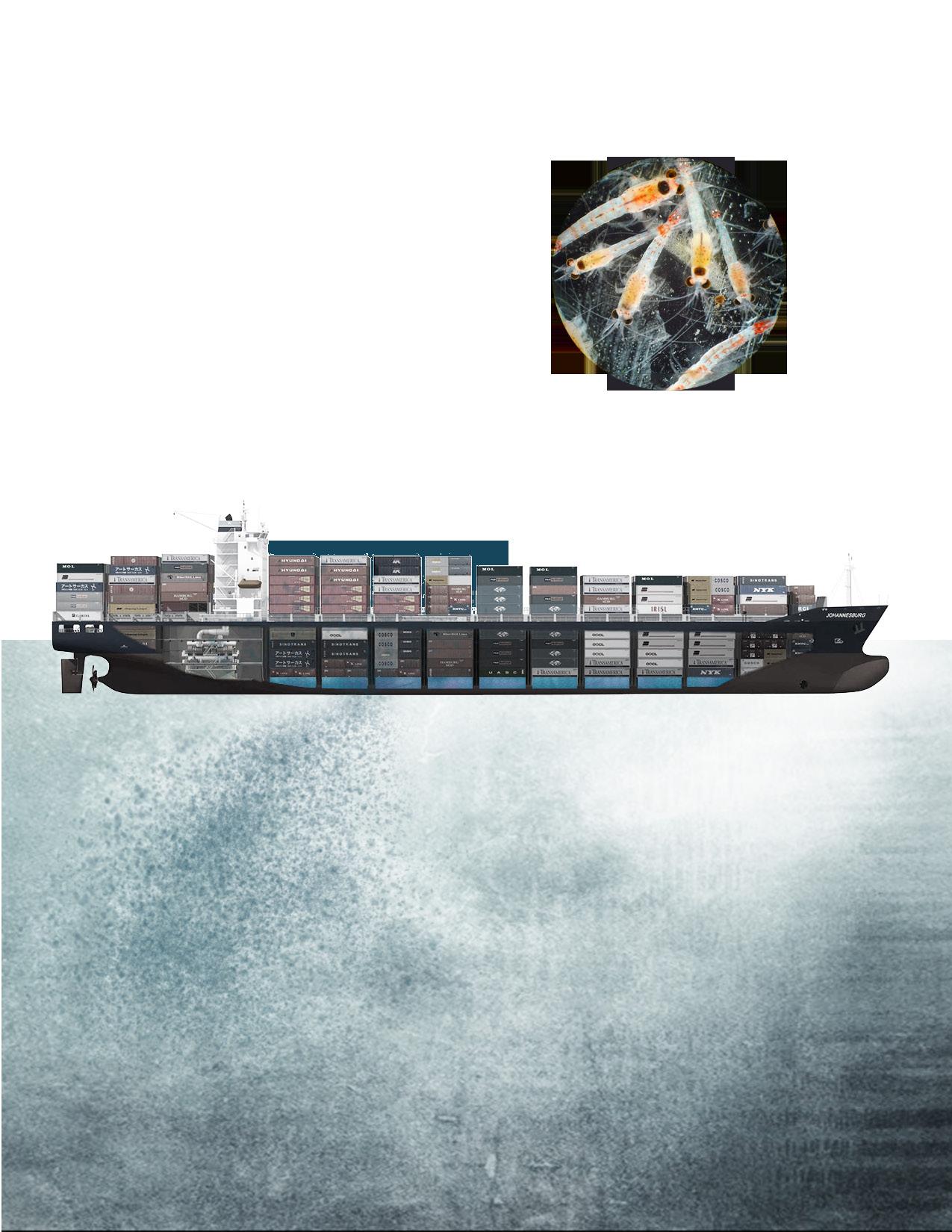

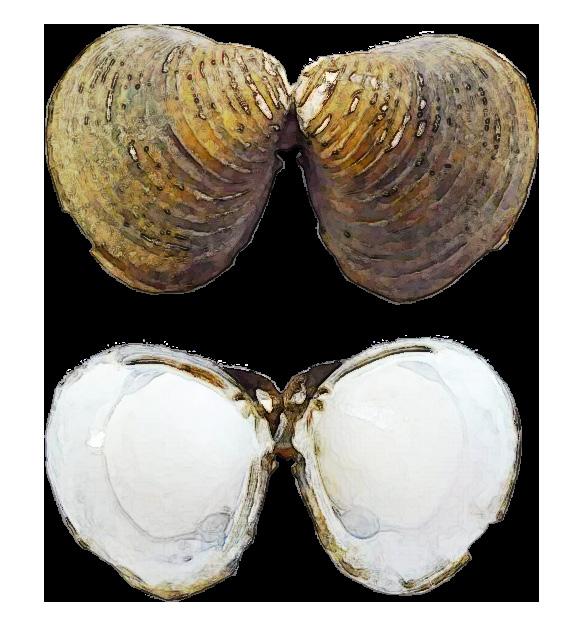

This is never the case with invasive species - no flower or crab shows up with the goal of destroying an ecosystem. They were not even in control of their journey to a new land - often they are accidental stowaways in ship’s ballasts or ride along with other natural products. These animals and plants are simply acting upon their biological drive to continue life and reproduce. The problem arises when their reproduction negatively affects their new habitat. With no natural predators, they are able to out-compete other species and dominate formerly diverse ecosystems.

Advertisement

Invasive species are a product of a more connected world. We see them appear with waves of new trade, immigration, and even trends across time. Historically, it took significant effort to move a plant or animal across the world. As globalization began to collapse time and distance in the 16th century, the nascent invasive was ready for its global debut. When we look at a map of everywhere the European Green Crab is today, we see how distant habitats may be more similar than expected. Boston, Nantes, Melbourne, and Seattle all support the crab’s life. What other connections can they expose?

When colonists first came to the US, they did not adjust to their new surroundings but reshaped them to become more familiar, more like their homes in Europe. Grain, the basis of our diet even today, could be considered an invasive species. It has taken over much of America. We don’t consider it as such because humans have complete control over it, but would the original prairie plants and animals see it the same way? Perhaps ‘invasive’ implies an outlook as opposed to an objective category. Garlic Mustard, considered an invasive today, arrived with early colonists as a medicinal herb. Now, it carpets forest floors across the country and has “no value.1” While it does compete with native wildflowers in some areas, especially sunnier regions, it has found a niche in other areas where few green leafy plants grew before. It, like many other invasives, thrives in the ruined landscapes industrialization and capitalism has left. Is it invading these landscapes?

Or is the coal mine the invasion? Like grain, Garlic Mustard and the other invasives in this book, is edible (although not the basis of an entire diet). We seem to have forgotten its use, what made it so important as to carry it on a dangerous journey across the world, and now only see its harm.

Early invasive species, like Garlic Mustard, required care to make their way across the world. We intentionally brought them with and cultivated them upon arrival. As the speed of trade increased and ship technology changed, more species were able to ride along without awareness on our part (or theirs). Beginning in the late 19th century, ships began using ballast water for stability and maneuvering control2. Before any regulation was put in place, ships would fill up their ballast at one port as needed and dump at their destination. Quite literally, they were mixing ecosystems. Many species unintentionally went along for the ride, including small crustaceans, fish, and mussels.

Referring to the arrival of new species as an ‘invasion’ reveals fear. Fear it will destroy an ecosystem and alter it beyond recognition. Fear we will lose desirable native (or ‘good’ exotic) plants and animals. Fear of a negative change in general. While these are all outcomes, some of which are happening already, it is not the entire story. Invasives can show us another way of looking at the world. They are tough, surviving long journeys, thriving in ecosystems that evolved without their needs. They carry histories of other places, flavors from around the world, and hints of different environments. As the world globalizes and heats up, they continue to prosper, despite our best efforts to remove them.

Another mindset would be to view them as potential. The ecological future of the world is becoming increasingly uncertain. With the changes that are expected to occur due to climate change, many dense centers of population will become unlivable, spurring even greater global movement. Plants will also migrate to escape nonviable conditions. Life will be in a rapid state of re-adjustment, of learning to live in new, unfamiliar environments, even if they are in the same physical location as previously. Our invasive species excel at this, surviving against the odds. Their fortitude can be a model for all of life. Rather than see them as strange and unsafe, we can start to look at them as cosurvivors. As they continue to flourish, they provide us food and a way forward. We can recognized their history as our history, one of a species striving for survival, finding it in the most unlikely of places with relations that span the globe.

Species animals

Plants