TheMethodsofNeuroethics

ElementsinBioethicsandNeuroethics

DOI:10.1017/9781009076173 Firstpublishedonline:January2024

LucaMalatesti UniversityofRijeka

JohnMcMillan UniversityofOtago

Authorforcorrespondence: LucaMalatesti, lmalatesti@ffri.uniri.hr

Abstract: ThisElementoffersaframeworkforexploringthe methodologicalchallengesofneuroethics.Theaimistoprovide aroadmapforthemethodologicalassumptions,andrelatedpitfalls, involvedintheinterdisciplinaryinvestigationoftheethical andlegalimplicationsofneuroscientificresearchandtechnology. Thesepointsareillustratedviathedebateabouttheethicalandlegal responsibilityofpsychopaths.Argumentandtheconceptualanalysisof normativeconceptssuchas ‘personhood’ or ‘humanagency’ are centraltoneuroethics.TheElementdiscussesdifferentapproachesto establishingnormsandprinciplesthatcanregulatethepractices addressedbyneuroethics,andthatinvolvetheuseofsuchconcepts. Howtocharacterisethepsychologicalfeaturescentraltoneuroethics, suchasautonomy,consent,moralunderstanding,moral motivation,andcontrolisamethodologicalchallenge.Inaddition, thereareepistemicchallengeswhendeterminingthevalidityof neuroscientificevidence.

Keywords: neuroethics,argument,conceptualanalysis,responsibility, psychopathy

©LucaMalatestiandJohnMcMillan2024

ISBNs:9781009495103(HB),9781009074902(PB),9781009076173(OC)

ISSNs:2752-3934(online),2752-3926(print)

1Introduction

Thereisarangeofattitudestowardsthemethodsofneuroethicalresearch. Neuroethicsisaninterdisciplinary fieldthatinvestigatestheethicalsignificance ofadvancementsinneuroscienceforindividualsandsociety.Itishighly responsiveto,andmotivatedby,developmentsinourunderstandingofneurologyandtheneurosciences.1 Methodologicalviewsexplicitlyorimplicitly guideneuroethicalinvestigations.However,therearefewsystematicattempts atclarifyingwhatisinvolvedindoingneuroethicswell.2

Byfocussingonexemplarsofneuroethicalresearch,ouraimistoshowhow methodologicalassumptionscanhaveanegativeimpactuponneuroethics.3 Moreover,wemakerecommendationsabouthowtoavoidsuchpitfalls.By identifyingthesemethodologicalproblemsandshowinghowtheycanbeavoided wehopetochartapathforthosenewtoneuroethicsandtogivethosemore establishedinthisareaareasontopauseforthoughtandreflectuponhow neuroethicscanthrive.

FollowingAdinaRoskies’ distinction,ourdiscussionconcernswhatshecalls the ‘neuroscienceofethics’ asopposedtothe ‘ethicsofneuroscience’ . 4 Research ofthelatterkindfocussesupontheethicalissuesraisedbyneuroscientific researchandmodificationsofthebrain.Thistypeofresearchhassparkedintense debatesaboutthemoralpermissibilityordesirabilityofmoral5 orcognitive enhancement6 bymeansofactualor,moreoften,hypotheticalinterventions basedonneuroscientific findings.7 Ontheotherhand,theneuroscienceofethics focussesonhowadvancementsinourunderstandingoftheneuralunderpinnings ofbehaviourmightaffectourviewsonethicalunderstandingandmotivationand offerinsightintothenatureofagency.

Weinvestigatemethodologicalissuesintheneuroscienceofethicsbyfocussingonrecentdebatesaboutresponsibility.Moralandcriminalresponsibility andfreewillareperennialissuesinphilosophy,sopriortotheenhancement debate(whichenquiresintotheimplicationsofusingnewtechnologiesfor increasinghumanwell-beingbeyondremedyingillness)mostofthephilosophicalinterestinneurosciencewasdirectedtowardsconditionsthatappeartoraise importantquestionsaboutresponsibility.Moralphilosophershavealsobeen interestedinneuroscientificevidencethatmightlendsupporttorationalistor sentimentalistmoraltheories,sothattoohasbeeninvestigatedinsomedepth.

1 Clausen&Levy,2015; Glannon,2011; Illes&Federico,2011; Levy,2007a; Roskies,2016

2 Boyleetal.,2022; Racine&Sample,2017

3 InthisElement,weexpanduponourarticle ‘Somemethodologicalissuesinneuroethics’ (Malatesti&McMillan,2021).

4 Roskies,2016 5 Douglas,2008; Persson&Savulescu,2012

6 Savulescu&Bostrom,2009. 7 Birks&Douglas,2018.

Weproceedasfollows.Inthe nextsection,weadvancethethreecoreideas thatframeourmethodologicalinvestigations.First,methodologicalclaims concerningneuroethicsshouldfocusonhowreasonedconclusionsarereached inneuroethics.Second,suchwaysofreasoningshouldbedescribedand assessedbyregardingneuroethicsasaninterdisciplinary fieldandnotas adisciplineitself.Finally,thereareatleastthreedifferentaimsofneuroethical reasoning,whichwedescribeasdescriptive,revisionary,andeliminative.

Havingsetoutthisgeneralframework,weintroduceanargumentativescheme (AS)thatwetaketocharacteriseacentralfamilyofreasoninginneuroethics.This schemeallowsustoexplicatecentralmethodologicalissues.Giventhatweapply thisAStothecasestudyofthecriminalandmoralresponsibilityofpsychopaths, wedescribeindetailthenotionofresponsibilityandtheconstructofpsychopathy. In Section3,wefocusonmethodologicalissuesandoptionsalongwiththe eventualcostsandbenefitsthatemergeontheethicalsideofneuroethical investigations.Weexaminetheattributionofmoralandlegalresponsibility withaparticularfocusonthetaskofdeterminingthepsychologicalstatesand capacitiesthatareprerequisitesforthem.In Section4,weexploretheconceptual issuesthatneedattentionwhenlookingathowneuroscientificresearchaffectsour practicesofholdingpeopleresponsible.In Section5,welookatthechallenges relatedtotheevidencetobeusedinneuroethicalresearchinthiscontext.

2AFrameworkfortheMethodsofNeuroethics

2.1Introduction

Toaddressitsmethods,weneedaworkingaccountofwhatneuroethicsis. However,wedonotaimtoofferanexhaustiveaccounthereofwhatneuroethics isanditsscope.Thecurrentliteratureoffersextensiveaccountsofagreat numberoftopics,mainlinesofdebate,andresultsthataretakentofallwithin thedomainofneuroethics.8 Wecannotdescribeandtaxonomiseallthese debatestoofferadefinitionofneuroethics.Instead,wewillfocuson asignificantclassofneuroethicalinvestigationstoexplicateimportant,and oftenoverlooked,methodologicalissues.

Ourapproachisbasedonthegeneralviewofneuroethicsthatwewillsetout inthefollowingsubsections.Thisviewisbasedonthreegeneralassumptions. The firstisthatneuroethicsisbasedontheuseofarguments.Thesecondisthat becauseneuroethicsisaninterdisciplinary fielditsargumentsinvolvepremises thatcrossdifferentdisciplines.Thethirdassumptionisthatthesearguments crossthedescriptive–normativedivide.

8 Clausen&Levy,2015; Glannon,2011; Illes&Federico,2011.

TheseassumptionssolidifyintheformulationofanASthat,whenappliedto thecasestudyofthelegalresponsibilityofpsychopaths,enablesustoillustrate themethodologicalfeaturesofneuroethics.

2.2TheCentralityofArgument

Ourguidingconcernishowneuroethics,understoodastheneuroscienceof ethics,canreachreasonedconvictionsabouttheissuesthatfallwithinitsscope. Wethusworkwithinamethodologicaltraditionexemplifiedbytheworkof HenrySidgwick,whodescribesthemethodsofethicsas ‘anexamination,at onceexpositoryandcritical,ofthedifferentmethodsofobtainingreasoned convictionsastowhatoughttobedone’ . 9

Weconsidertheindividuationandevaluationofthe types ofreasoningor argumentsinvolvedinneuroethicalresearch.Ouranalysisfocussesonthe possiblepitfallsofwaysofreasoninginneuroethics.

Anargumentisarationalorlogicalprocesswherepropositions,the premises oftheargument,areusedtoinferapropositionthatconstitutesthe conclusion oftheargument.Forexample,thefollowingisawrittenexpression ofanargument:

ArgumentA.1

(1)Ifneurosciencecanexplainthecausesofcriminalbehaviours,then neurosciencecanbeusefulfortheadministrationofcriminallaw.

(2)Neurosciencecanexplainthecausesofcriminalbehaviours. Therefore:

(3)Neurosciencecanbeusefulintheadministrationofcriminallaw.

Thepremisesoftheargumentarethepropositions(1)and(2),andproposition (3)isitsconclusion.Letusnowseewhatisinvolvedinevaluatingarguments.

Anargumentissaidtobevalidifthetruthofitspremisesguaranteesthetruthof itsconclusion.Thismeansthatpremisesofferagoodsupportfortheconclusionor, asisusuallysaid,theconclusionfollowslogicallyfromthepremises.Forexample, ArgumentA.1 isvalidif,werethepremisesbothtrue,theconclusionwould logicallyfollow,andtheconclusionwouldalsobetrue.Itisworthpausingfor amomenttoconsiderinsomedetailwhatismeantby ‘thevalidityofanargument’ Validargumentsdonotalwayshaveatrueconclusionortruepremises.

Validitycanbedefinedasfollows:

Anargumentisvalidifandonlyif, if allitspremisesaretrue, then itsconclusion mustbetrue.

9 Sidgwick,1874/1981,p.vii.

Thismeansthatanargumentisvalidwhenallitspremisesaretrueandtheylead ustoatrueconclusion.Thedefinitionofvaliditydoesnotrequirethatavalid argumentnecessarilyhasatrueconclusion.Itwouldhaveatrueconclusiononly ifallitspremisesweretrue.Similarly,avalidargumentdoesnotneedtohaveall truepremises.Considerthefollowingexampleofavalidargumentwithafalse conclusionandafalsepremise:

ArgumentA.2

(1)Ifcurrentneuroimagingtechniquespermitustoreadminds,then languageuseisobsolete.

(2)Currentneuroimagingtechniquespermitustoreadminds. Therefore:

(3)Languageuseisobsolete.

Adoptingtheconclusionoftheargumentwouldbeabadidea,asitisfalse.Butthe argumentisvalid.Werepremises(1)and(2)true,theconclusion(3)wouldalsobe true.However,premise(2)issurelyfalse.Whetherpremise(1)istrueorfalseisopen tofurtheranalysisandevidence,soitislessobviouslyfalseandupfordebate.Letus nowconsiderfurther,inmoredetail,whatismeantbythe ‘validityofanargument’ .

Anargument’svaliditydependsonits logicalform.Tounderstandthelogical formofanargument,observethatthepremisesandconclusionof ArgumentA.2 canbereformulatedbymeansofletters,whichreplacethepropositions:

(1)IfP(currentneuroimagingtechniquespermitustoreadminds),then Q(languageuseisobsolete).

(2)P(currentneuroimagingtechniquespermitsustoreadminds). Therefore:

(3)Q(languageuseisobsolete).

Thus,werealisethattheformoftheargumentisthefollowing:

(1)IfP,thenQ. (2)P. Therefore: (3)Q.

Theaboveschematicstructureexhibitsthelogicalformoftheargument.The logicalformofanargumentdependsonthelogicalstructureofthepremisesand theirconclusion.Forexample,intheargumentabove,nomatterthespecific propositionsthatwecansubstituteinsteadofthevariablesPorQ,the first premisemusthavethefollowinglogicalform:

(1)IfP,thenQ.

Thislogicalformcharacterisesa conditional,wherePiscalledthe antecedent andQthe consequent.Moreover,thesecondpremiseoftheargument,mustbe identicaltotheantecedentofthe firstpremise(1):ifPthenQ,thatis,itmustbe thepropositionP.

Thisschematicstructureis formal becauseitdescribesabstractfeaturesthat canbesharedbydifferentarguments.Consideragain ArgumentA.1:

(1)Ifneurosciencecanexplainthecausesofcriminalbehaviour,then neurosciencecanbeusefulforcriminallaw.

(2)Neurosciencecanexplainthecausesofcriminalbehaviour.

Therefore:

(3)Neurosciencecanbeusefulforcriminallaw.

Byreplacingthepropositionsthatappearinit,weobtain:

(1)IfP(neurosciencecanexplainthecausesofcriminalbehaviour),then Q(neurosciencecanbeusefulforcriminallaw).

(2)P(neurosciencecanexplainthecausesofcriminalbehaviour).

Therefore:

(3)Q(neurosciencecanbeusefulforcriminallaw).

Thismeansthatthisargumenthasthelogicalform:

(1)IfP,thenQ.

(2)P. Therefore: (3)Q.

Letusnowlookatafundamentalrelationbetweenthelogicalformofan argumentanditsvalidity.Itisafundamentalcontributionoflogicthatarguments arevalidinvirtueoftheirlogicalform.Whatmakes ArgumentA.1 and Argument A.2 validisthefactthattheyarebothinstancesoftheschemewehaveintroduced:

(1)IfP,thenQ. (2)P. Therefore: (3)Q.

Formalargumentswiththatstructureareknownas modusponens.Besides modusponens,logicianshaveidentifiedthelogicalformofothervalidarguments. Modustollens isperhapsthesecondmostcommonargument.Itis anotherfundamental,validASandhasthefollowingform:

(1)IfP,thenQ. (2)NotQ.

Therefore:

(3)NotP.

Letusconsiderthefollowinginstanceof modustollens:

(1)Ifthemoralcapacitiesofindividualsareenhancedwithbiomedical interventionsupontheirbrain(P),thenbiomedicalinterventionsuponthe brainwillincreasetheirfreedomofchoice(Q).

(2)Biomedicalinterventionsinthebraindonotincreasethefreedomof individuals(notQ).

Therefore:

(3)Themoralcapacitiesofindividualsarenotenhancedbybiomedical interventionsupontheirbrain(notP).

Therearemanyothervalidargumentativeforms,butasurprisingnumberof argumentsinneuroethics,bothsoundandweak,drawuponvariationsof modus ponens and tollens

Our firstmethodologicalrecommendation – thatweshouldlooktothemethods employedinneuroethicsforreaching ‘reasonedconvictions’– ispremisedupon theassumptionthattheargumentsinthis fieldshouldbevalid.However,itisnot enoughtoreflectonthedefinitionofthevalidityofanargumenttoreachareasoned conviction.Validityisbestthoughtofasonlyanecessaryconditionofgood neuroethics.Thisispartlybecausevalidargumentsgeneratetrueconclusions onlywhentheirpremisesaretrue.Thus,amorecompleterequirementisthat goodneuroethicsshouldoffervalidargumentswithtruepremises.

Anargumentissaidtobe sound whenitisvalid,andallitspremisesaretrue. Considerthefollowinginstanceof modusponens:

(1)IfatownisclosetoLakeTaupo,thetownisinNewZealand.

(2)TūrangiisclosebyLakeTaupo. Therefore:

(3)TūrangiisinNewZealand.

Beinganinstanceof modusponens,theargumentisvalid.Thus,ifitspremises aretrue,itsconclusionmustalsobetrue.Boththepremisesofthisargument,as amatterofgeography,aretrue.Therefore,theconclusionistrue.

Wecan,thus,saythatanaimofgoodneuroethicsistooffersoundarguments. Thismeansthatbesidesusinglogicallyvalidargumentsneuroethicistsshould attempttodemonstratethatthepremisesoftheirargumentsaretrue.So, acentraltaskofmethodologicalinvestigationistoinvestigatethesourcesof evidencethatcanbeusedinneuroethicstosupportthetruthofthepremises usedwhenadvancingarguments.Aswewillshow,itistheuseofevidencethat

isoneoftheprincipalpitfallsofneuroethics.However,beforeaddressingthis task,wemustcomplicatefurtherourpictureofreasoning.Whatwehavesaidso farconcerns deductive arguments,thatisargumentsthatwhenvalid,leadfrom truepremisestoatrueconclusion.Butthereareotherimportantargumentsthat arenotdeductive.

Therelationshipbetweenthepremiseandconclusionofanargumentisnot alwaysdeductive.Forinstance,considerthefollowingpremiseandinference:

(1)Therearepawprintsinthesnow.

Therefore:

(2)Mycatwalkedinthesnow.

Ifweownacat,knowthatitmighthavebeenoutandabletowalkinthesnow, knowthattherearenotmanyothercatsaroundthatmighthavewalkedthere,we mightformthebeliefthatourcatwalkedthere.Wemightnotattachagreatdeal ofconfidencetothatbelief,andviewitassomethingthatcouldeasilybe rebuttedbysomethinglikethepresenceofothercats.Nonetheless,thatkind ofinferenceispartofhowwemakeinferencesandformbeliefseveryday.

Thistypeofreasoningisan ‘inductive’ argument,whichofteninvolvesgoing beyondthepremises.Inductiveargumentsarenotformallyvalidbutcanstillbe consideredgoodorbadbasedonhowreasonabletheinferenceis.Inthis example,ifIknowthereareothercatsaroundorthatmycatisoldandarthritic andusuallyavoidswalkinginthesnow,myinferencemightbebad,orpoor giventhatIhadreasonstorebutthatinference.

Whileafullexplanationofthefundamentalsoflogicisbeyondthescopeof thisElement,thesebriefremarksaresufficientforourpurpose:ouremphasis uponthekindofreasoningthattypifiesneuroethicsandwhatthisshowsaboutits methods.10 Wewillnowfocusuponhowevidenceisgatheredforthepremisesin thedeductiveandinductiveargumentsadvancedwithinneuroethics.

2.3NeuroethicsasanInterdisciplinaryField

Examiningthereasoningorargumentsofneuroethicsinvolves descriptive and evaluative components.Thedescriptivecomponentexplicatestheaimsthat guidesometypesofargument,thekindofevidencethatisadoptedinthese arguments,andthemethodsusedtoobtainit.Theevaluativecomponentofour methodologicalstudyhighlightscommonandpossiblepitfallsthatcanafflict thiskindofreasoningandargument.Wewillinvestigatehowtheseproblems derivefromtheinappropriateaimsthatarepursuedinsomearguments,and fromdefectivemethodsusedforgatheringevidence.However,toappreciatethe 10 Foranintroductiontoformalandinformallogic,see Cohenetal.,2019.

aimsandevidenceinvolvedinneuroethicalarguments,weneedapreliminary characterisationofneuroethicsitself.

Neuroethicsisaninterdisciplinary fieldratherthanadiscipline.Ratherthan beinganareathatistypifiedbycommontraining,assumptions,andinterests, neuroethics,likebioethics,isaninterdisciplinaryareacharacterisedbyasetof issues.Whendescribingbioethics,MargaretBattinclaimsthat:

nosinglebackground fieldamongthoseinitsmulti-hybridparentagehas becomedominant,andnobackground fieldhasbeeneitherexcludedor lionizedasaparticipantinbioethicsdiscussions.Doctorsdonothavethe finalsayinbioethicsdiscussions;neitherdolawyers;andneither,forthat matter,dophilosophersorthosefromanyofthemanyother fieldscontributingtobioethics.Bioethicsremainsdeeplyandthoroughlyinterdisciplinary.11

Herconceptionofbioethicsasfundamentallyinterdisciplinary,notexcluding relevantdisciplinesanddilemmadriven, fitswithhowweshouldviewneuroethics.Bioethicsandneuroethicsareunifiedbyasetofissuesthataresignificantandworthyofscholarlyattentionfromarangeofcognatedisciplines.Both facechallengesinbridgingtheinevitabledifferencesthatresultfromdrawing uponarangeofdisciplines.Whenwritingaboutthechallengesforbioethicsthat resultfromitsinterdisciplinarity,JohnMcMillandescribeswhathecallsthe ‘snootyspecialistspectre’ whichisamethodologicalpitfallforbioethics.

Attimes,theturfwarsofbioethicshavedescendedintosnootinesswhichhas donelittletopromoteinterdisciplinarity,andthatonitsownis amethodologicalspectre.Itisalsofairtosaythatthereisadegreeof condescensionfromsomephilosopherstowardthosewhoaredescribedas ‘bioethicists’,or ‘medicalethicists’ ... Philosophersarebynomeansalonein thistendency,sociologistsofmedicinesometimesseetheirdisciplineashaving alreadycarvedoutnichesthatbioethiciststhenthinktheyhavediscovered.12

Thereisasimilartemptationwithinneuroethicsforthecontributingdisciplinestoviewtheirperspectiveasauthoritativeorgoingtotheheartofthematter. Forexample,aphilosophermightseetheirexpertiseinthenatureofmoral reasoningasgivingthemaprivilegedperspectiveuponcentralissuesinneuroethics.Likewise,aneuroscientistmightviewtheevidencethattheybringto neuroethicsviafunctionalMRI(magneticresonanceimaging)asthebedrock uponwhichallneuroethicsshouldrest.Differencesinexpertiseareboththe opportunityandrationaleforinterdisciplinarityandoneofitspotentialpitfalls. Thismeansthatthemethodologicalchallengesforbioethicsandneuroethics areperhapsgreaterthanfordisciplineswherethereislikelytobemore convergenceuponwhatthecentralissuesareandhowtheyshouldbeaddressed.

Relatedly,theaims,typesofevidence,andthemethodsforgatheringevidence thatcharacteriseneuroethicalargumentswillreflectthatinterdisciplinarity.

Interdisciplinaritymustthereforebeconsideredintheindividuationandevaluationofneuroethicalarguments.Itisthusimportanttobeawarethatthewayin whichneuroethicsdrawsupondifferentdisciplinesandtranslatesacrosslevelsof explanationanddifferentkindsofexplanationcreatesarangeofmethodological pitfalls.Inevitably,whenreasoningina fielddrawsfromsuchdiversedisciplinesas neuroscience,philosophy,socialsciencesandthelaw,methodologicalproblemscan occurbecausetheworkcrossesdisciplinaryboundariesandnorms.Theseproblems canariseatalltheintersectionsbetweenthedisciplinesinvolvedinneuroethics.

Toillustratehowinterdisciplinarityaffectsneuroethicalreasoning,wewill explorethediscussionofcriminalresponsibilitywithinneuroethicsintheremainderofthisElement.Criminalresponsibilityandimpairmentstocognitionand emotionarerelevanttothelawanditisclearlyanimportantissueforneuroethics thatthisisappropriatelyaddressedbyinterdisciplinarity.Justasinthecaseof philosophy,whatisimportanttoacademiclawyersortolawyersduringacourt hearing,mightnotbewhatismostimportantinneuroscienceandrunstheriskof drawingproblematicinferencesfromresearch.Forexample,thepresenceofan atypicalMRIscanmightbeusedtodefendsomeonebeingtriedforanoffenceand givenasajustificationforareducedsentence.Whatthat findingshows,andany conceptualissuesimplicitininterpretingthe finding,runtheriskofbeingglossed overbecauseoftherelevancethatthe findinghasforthelegalissueathand.

Neuroscienceandneurosurgerycandrawconceptualextrapolationsfrom theirresearchabouthumanagencyormoralresponsibilitythatutilisephilosophicalorlegalmodesofreasoning.Whilethereiseveryreasontoencourage neurosciencetoengagewiththeethicalandphilosophicalimplicationsof research,thiscanresultinclaimsthatarenotphilosophicallyorlegallynovel, orwellgrounded.So,manyofthemethodologicalpitfallsofneuroethicsresult fromthedesirableintersectionofdifferingdisciplines;thereisthereforeaneed toreflectuponthemwithaviewtodevelopingneuroethicsasa fieldofinquiry.

Ourviewofneuroethicsasa ‘field’ ratherthana ‘discipline’ hasmethodologicalimplicationsforthekindofargumentsthatshouldbedeveloped. Adiscipline,asthenamesuggests,willtypicallyhaveasetofmethodological approaches,andgraspingthemwouldcountas ‘training’ inthatdiscipline.Most disciplineswillhaveasetofprojectsorintereststhatareviewedascanonicaland partofbeingtrainedinadisciplineishavingaknowledgeofthecanon.For example,inanalyticphilosophyanundergraduatedegreewilltypicallyinclude logic,epistemology,metaphysics,andethics.Metaphysicscanincludeseveral topicsbutislikelytoincludetheproblemoffreewillanddeterminism,while epistemologyislikelytoincludethetrue,justifiedbeliefaccountofknowledge.

Ofcourse,thereisvariationanddisagreementaboutwhetherthesefourareasand thetwoexampleswehavementionedarecanonical,butingeneralawell-rounded firstdegreeinanalyticphilosophywouldtakethisform.

Thismeansthat,formostdisciplines,thereareintereststhatarecentraltothe disciplineitself.Becausewethinkthatinterdisciplinaryareassuchasbioethicsand neuroethicsarejustifiedandunifiedbytheissuesthataretakentobeworthyof investigation,itisusefultonamethatunifyingsetofissues.Weusetheterm ‘domain’ tosignifytheissuesthataretakento beworthyofinvestigationwithin adisciplineorinterdisciplinaryarea.Thedomainofanalyticphilosophychanges anddevelopsovertimeasdifferentresearchquestionsareadopted;nonetheless,it includesperennialanddisciplinedefiningissuesthathavebeendebatedsince ancientGreekphilosophy.Philosophicalproblemssuchasthenatureofreality, what,ifanything,wecanknowforcertain,anddeterminismpersistandcontinueto bepartofitsdomain.

Interdisciplinaryareassuchasbioethicsandneuroethicshavedomainstoo,but theyarenecessarilydifferent.Bioethicsisaninterdisciplinaryresearchareathat hasbeendriveninpartbydevelopmentsinbiomedicineandsharpethical dilemmas.Itsdomainisthereforeappropriatelyissuedrivenandresponsiveto newissues.13 Inotherwords,thedomainofbioethicsishighlyresponsiveto emergingbiomedicalpossibilitiesandresultingethicalissues.Neuroethicsis similarinthatitismotivatedbyandhighlyresponsivetodevelopmentsinour understandingofneurologyandtheneurosciences.Forexample,newMRI findingsaboutdifferingpatternsofbrainactivationinpsychopathsandthose withoutthatdiagnosisarelikelytofeedintothedomainofneuroethics.The domainofneuroethicscanalsobedrivenbyhighprofiletragediesandpolicy responsestothem.Forexample,abouttwentyyearsago,intheUnitedKingdom, theconvictionofMichaelStoneforviolentassaults,whosufferedfrompsychopathyandwasunabletoaccesstreatmentforhiscondition,werethecatalystfor apolicyresponseandsubsequentneuroethicaldebateaboutpsychopathy.14

Whilewedonotwishtobetooprescriptiveaboutthedomainofneuroethics becauseitisaninterdisciplinary fieldunifiedbyanengagementwithneuroscience,theimportanceofadomainforunifyingit,anditsmethods,hasimplicationsforhowneuroethicsshouldproceed.Whilethedomainofneuroethicswill becontestedandwillevolve,itisimportantthatscholarshiptargetsitsdomain. Thisisbecausethedomainunifiesandgivesneuroethicsitspurpose,so scholarshipshouldbedirectedtowardstheissuesthatmatterandthatjustifyit.

13 Battin,2013; McMillan,2018

14 Burnsetal.,2011; DepartmentofHealth,HomeOffice,&HMPrisonService,2005; Malatesti& McMillan,2010.

Thewaysinwhichresearchinneuroethicsconnectswithadomainarewhatwe term ‘relevance’ conditions.By ‘relevance’ wemeantheissuesandmethodstaken tobeappropriatewithin aninterdisciplinary fieldordiscipline.Inotherwords,there aresomerestrictionsuponthequestionsrelevanttoagivendiscipline.Forexample, researchthatclaimstobeneuroscience,butthatdoesnotdrawuponanyofthe investigationtechniquesofneuroscienceandinsteadmakesclaimsaboutthe functionofthebrainbaseduponareadingoftheOldTestament,wouldfailour ‘relevance’ condition.Giventhedomainofneuroscience,theologicalexegesiswill notfurthertheaimsofthatdiscipline.Itmightbethatanoverlyphilosophical approachtothemoralresponsibilityofpsychopathswouldfailtomeetrelevance conditionstoo.Ifphilosophicalworkfailstocharacterisepsychopathyinawaythat wouldberecognisedbythoseworkingwithinneuroscienceorclinicallywith psychopaths,thatwouldfailtoconnectthedomainandberelevanttoneuroethics. Relevancematterstoneuroethics,becauseofitsinterdisciplinarityandthe likelihoodthatthemethodsandinterestsofthecontributingdisciplineswill determinethedomainofneuroethics.Themethodsandissuesofneuroethics shouldnotbesolelydrivenbywhatlaworphilosophyseesasrelevanttothe domainsoftheirdisciplines.

WewillnowconsideranASthatwillhelpustomoveforwardinouranalysis ofsomecentralmethodologicalissuesinneuroethics.

2.4AGeneralArgumentativeSchemeandaCaseStudy

Manyneuroethicalinvestigationscanbeinterpretedasadoptingthefollowing AS,thatis,aninstanceof modusponens:

(1)IfsubjectShasfeatureG,thenwe ought todoAtoS.(targetpractice)

(2)ShasG.(bridgingpremise)

Therefore:

(3)We ought todoAtoS.(recommendation)

Considerthefollowingexampleofanargumentwiththisstructure:

(1)Ifathleteswhoengageincontactsportsriskdevelopingchronic traumaticencephalopathyduetoconcussion,thenwe ought tointroduce regulationsincontactsportstoreduceconcussions.

(2)Athleteswhoengageincontactsportsriskdevelopingchronic traumaticencephalopathyduetoconcussion.

Therefore:

(3)Weoughttointroduceregulationsincontactsportstoreduceconcussions.15

Wehaveitalicised ‘ought’ inpremise1oftheASbecausenormativeor prescriptivepremiseshaveimplicationsforhowweviewthevalidityofan argument. ‘Ought’ isanactionguidingverb,itimpliesthatacourseofactionof somekindshouldfollow.Butthereareseveraldifferentkindsofprescription; theycanbeethical,aesthetic,orappealtoself-interestortoscientificintegrity, tonamejustafew.Ourviewisthattheprescriptionsmostcommontoneuroethicsarelegalorethical.Thatisbecausemanyoftheissuesthatcharacterise thedomainofneuroethicsareaboutwhatourethical,legal,orpublicpolicy responseshouldbetoanissue.

IntheASargumentjustcited,the firstpremiseisaboutarecommendationor prescriptionthatisbasedonlegalormoralprinciplesthatarerelevanttoan existingpracticethatisinthedomainoftheneuroethicalinvestigation.Inthe caseoflegalresponsibilityandtheinsanitydefence,thiscouldbetheclaimthat anindividual(S)wasincapableofunderstandingthenatureoftheiraction(G)at thetimeofcommittingacrimeandtheythereforeoughtnotbeheldlegally responsible(A).16

ThesecondbridgingpremiseinASisadescriptiveclaimsupportedby neurosciencethatoffersaninterfacewiththepracticementionedinthe first premisebymeansofafeature(G).Forinstance,whenconsideringlegal responsibility,thiscouldbetheclaimthatneuroscienceoffersevidencethat, duetosomepeculiaritiesinthebrain,anindividualorclassofindividualsis incapableofgraspingthenatureoftheiractions.

Theconclusionofthisschematicargumentisthe finalrecommendationofthe neuroethicalresearch.Keepingwiththeexamplethatwehaveusedsofar,thisis therecommendationthattheclassofindividualsthathasfeatureG,inourcase thelackofunderstandingordiminishedcapacitytounderstandthenatureofthe action, ought tobeexculpated.

Clearly,theASsupportsourgeneralviewofneuroethicsasaninterdisciplinary field.First,itisimportanttohighlightthatmanyargumentsshareits structureandrelyonpremisesthataredescriptiveandnormative.Generating soundargumentsthatdrawupondescriptionsandthenreachnormativeconclusionsisakeytogoodmethodologyinneuroethics.That,too,isachallengefor theinterdisciplinarityofneuroethicsbecausewhenitcomestolegalnormativity,lawyersarelikelytohavespecificinterestsandknowledge,whereasphilosophersmightgravitatetowardsethicalnormativity.

Neuroscience,neuropsychology,andthecognitivesciencesseemtofallmore towardsthedescriptivesideofneuroethics.IntermsofourAS,thesearethe disciplinesthatofferevidentialsupportforthesecondpremise,whichwecall

16 Meynen,2016.

thebridgingpremise.Theneuroethicalinvestigationmustrelyonresultsfrom thesedisciplinestoestablishthatanindividualoraclassofindividualshas neurologicalandcorrelatedpsychologicalfeatures,whichweschematically indicatewithG.Thisgroundstheapplicationofageneralconditionalprinciple, thatis,the firstpremiseofschemeAS,toderiveanormativeconclusionabout whatweoughttodowiththoseindividuals.

Itisimportanttorecognisethatthereareimportantdescriptivedimensions whencharacterisingthenormativepracticesthatareevidentiallyrelevantwhen consideringthisAS.Forinstance,inlawthereareimportantdescriptiveissues tobetackled.Whenassessingthenormativeissuesthatarerelevantto aneuroethicalargumentthatengageswithlaw,anaccuratedescriptionofthe lawandtheprinciplesthatregulatethatpracticeisneeded.Aswewillseein Section2.4.1,thisdescriptivecomponentisnotsimplyamatterofreadingthe relevantlawsfromtherelevantlegislation.Moreover,inneuroethicalinvestigationstheexplicationofthetargetpracticemightalsorequireinvestigating how,defacto,thesenormativeprinciplesareused.Neuroethicalinvestigations thatfocusontheethicalaspectsofatargetpracticemightneedinformation abouttheethicalattitudesofthemainactorsinvolved.So,forinstance,descriptivesociologicalqualitativeorquantitativeinvestigationsoftheseattitudes mightalsobenecessary.

Besidesdetailingthebackgroundnecessaryforunderstandingthetarget practice,thedescriptionsofferedbysocialscientistsmightalsohaveamore directroleintheformulationofneuroethicalrecommendationsorprescriptions.RaymondDeVriesclaims: ‘ indescribingthe is weareimplyingan ought ’ 17 Hearguesthatasociologicalanalysisofatargetpracticemight revealthepresenceofsystematicinjusticesormalpracticesthatcallfor normativesolutions.Moreover,healsohighlightshowsociologicalstudies ofneuroethicalpracticecanaddressethicalshortcomingsintheworkofits practitioners.

HavingsetoutthegeneralASthatwetaketobecentraltoseveralneuroethicalinvestigationsandproposals,wecanmovetothecoreofourmethodological investigation.Toillustratethepointswehavejustmade,wewillexplainthe neuroethicaldiscussionaboutthecriminalresponsibilityofpsychopaths.There aretwoprincipalreasonswhywediscusspsychopathy.First,thisdebate presentsmanyinstancesofneuroethicalreasoningthatinvolveschemeAS andthemethodologicalchallengesthatmustbefaced.Wewillshowhowour conclusionsaboutthiscasecanbeextrapolatedtootherneuroethicaldebates. Second,weconsiderpsychopathybecauseinthelasttenyearswehave

17 DeVries,2005,p.26.

followedandcontributedtodifferentstreamsoftheneuroethicaldebateonthe appropriatesocialresponsetopsychopaths.18

Therefore,intheremainderofthisElementweexplorethemethodological assumptionsandpossiblechallengesinvolvedinadvancingthefollowing instanceofschemeAS:

(1)IfsubjectsShavefeatureG,thenwe ought notholdsubjectscriminally responsiblefortheircrimes.(targetpractice)

(2)PsychopathshaveG.(bridgingpremise) Therefore:

(3)We ought nottoholdpsychopathscriminallyresponsible. (recommendation)

Letuspreliminarilyintroducethekeynotionsinthisargument.

2.4.1CriminalandMoralResponsibility

Responsibilityisacentralaspectofpersonhoodanditisatthecoreofethicsand thelaw.Holdingapersonresponsibleforwhattheydoimpliesseveralsignificantthingsaboutthatpersonandisagroundforothersandthepersonhimselfto haveattitudesandreactionstowardsthatperson.Itcanbefundamentalto whethersomeoneisviewedasapersonandabearerofrights. Ifanindividualisresponsibleformurder,aconvictionforthatcrimewillresult inimprisonment,atleast.Ifapersonisresponsiblefornotpayingtaxesthisis agroundfor finingthemaccordingly.Ifsomeoneisresponsibleforhurtingthe feelingsofsomeoneelsewithindelicatewords,thisisareasonforathirdpersonto adoptacriticalattitudetowardsthem.Viewinganotherpersonasanagentwhois anappropriatetargetforwhatPeterStrawsondescribedas ‘reactiveattitudes’ will determinethewayinwhichthatpersonisengagedwithintheworld.19 Strawson notedthatwhenengagingwithentitiesintheworldwecanadopt ‘reactive’ or ‘objective’ attitudestowardsthem.Inthecaseofentitiessuchastablesandchairs, weadoptan ‘objective’ attitude;wetreattablesandchairsastheobjectsthatthey are.Evenifwebangedatoeintoatableandsaid ‘stupidtable’,wewouldnotbe literallyorappropriatelyadoptingareactiveattitudetowardsthattable. ‘Reactive’ attitudes,ontheotherhand,involveviewingtheentitythatisatthecentreof attentionasanappropriatetargetfortheseattitudesbecauseofitsabilitytorespond toreasons.So,someonewhodoessomethingkindis,invirtueofbeingaperson, anappropriatetargetforareactiveattitudesuchas ‘praise’ or ‘gratitude’

Attributingordenyingresponsibilitytoagentsimpactstheirlivesgreatly,as wellasinfluencinghowtheyinteractwithothersaffectedbytheiractionsand

18 Malatesti&McMillan,2010; Malatestietal.,2022. 19 Strawson,1993.

thenatureoftheirsocialworld.Insituationswherewesuspendtheattributionof reactiveattitudestoaperson,thatresultsinquitearadicalchangeintheirstatus. Itisthereforeunsurprisingthattheevidentialgroundsforattributingresponsibilityareofparamountimportanceforethicalandlegalthinking.

Attributingresponsibilitytoapersonisbaseduponevidenceabouttheir psychologyandthecontextinwhichtheiractionstakeplace.Philosophy andlawusuallyrequirethatanagentisresponsiblefortheiractionswhen theyissueintheappropriatewayfromt heirvolitionalandcognitivemental states.Thus,anagentshouldhavetheintentiontoperformanactionand knowthenatureoftheactiontheyareperforming,andthisactionshouldbe undertheircontrol.Anagentwhoaccidentallyhurtsanotherpersonwithout havingtheintentiontodoso,orknowingthattheyaredoingso,wouldnot usuallybeheldresponsibleforthataction.Similarly,anagentwhoknows thattheyarehurtinganotherpersonbutisdoingsobecausetheyhavebeen forcedtodoso,andthereforelackscontrolofthataction,wouldnot ordinarilybeheldresponsibleforit.Thesetwokindsofexcusewerenoted byAristotleinthe NicomacheanEthics : ‘ Thingsthathappenbyforceor throughignorancearethoughttobeinvoluntary.Whatisforcediswhathas anexternal fi rstprinciple,suchthattheagentorthepersonactedupon contributesnothingtoit – ifawind,forexample,orpeoplewithpower overhimcarryhimsomewhere ’ 20

AsAristotleobserves,beingphysicallycompelledtodosomething,as apersonforcedtodosomethingatgunpointmightbe,oranobjectcapableof onlyfollowingcausallaws,isadefenceagainstresponsibility.Likewise,ifan actionisperformedfromignoranceofasituationthatanagentcouldnothave remedied,thisisalsoadefence.Aswewillshow,bothofthosedefencescan playaroleintheattributionofmoralresponsibility.

Neurosciencecaninterfacewiththesetwodefencesandimpactthewayswe holdpeopleresponsibleinseveralways.Itoffersevidencethatcandescribe, explain,predict,andeventuallymodifythementalstatesandcapacitiesthatare takenintoconsiderationwhenweattributemoralandlegalresponsibility.

2.4.2Psychopathy

Literature, film,andpopularculturehavetendedtoportraypsychopathsascoldbloodedkillers.Inthe filmandnovel NoCountryforOldMen, 21 AntonChigurh isavillainwhokillshisvictimsbyplacingagas-poweredboltstunnerontheir foreheadsanddespatchingthembeforetheyseethedanger.Hisemotional detachmentispartofwhatmakesthisplotfeaturesuccessfulandsochilling: 20 Aristotle,2004,p.37:1110a. 21 McCarthy,2006.

theliveshetakesevokenoreactioninhimandthatispartofwhatputshis victimsateaseandmakeshimeffective.Thischaracterhasbeendescribedby apsychologistwhohasinterviewedpsychopathsasthe ‘mostfrighteningly realistic’ portrayalofapsychopath.22

Thisportrayal,however,isincompleteandreinforcesastereotypeabouthow thetypicalpsychopathpresentsthathasexercisedanegativeeffectinneuroethicaldebates.23 Weareallfamiliarwiththecold-bloodedserialkillerandthereis nodenyingthattheyexist.Wethinkthatthisspecificwayinwhichpsychopathy canpresenthasbecomethedominantwayofdescribingtheconditionanditis thisdescriptionthathasoftenbeenanalysedbyphilosophers,scientists,and lawyersinterestedinhowpsychopathyillustratesthenatureofmoralresponsibilityandpunishment.However,aswewillseeintheremainderofthisElement, thereisalivelydebateinthescientificliteratureabouthowtodescribepsychopathy,orevenwhetheritisstillviableasaconstruct.24

Inanycase,whiletherewillalwaysbecontroversyanddisagreementabout psychopathy,thereisnodoubtingtheinfluenceofthecharacterisationsof psychopathyinHerveyCleckley’s TheMaskofSanity, firstpublishedin 1941,andtheconceptualisationofthisconstructbyRobertHareinhis PsychopathyChecklist– Revised(PCL-R).25 Whilewewillconsiderinsome detailCleckley’scharacterisationin Section4.2.2,webeginbyfocussingon PCL-R,aclinicalratingscaletomeasurepsychopathicpersonalitytraits.

InrecentyearsanentireresearchparadigmforthescientificstudyofpsychopathyhasevolvedaroundthePCL-R.Thisisatoolthatscoresbasedonthe followingtwentyitems:

(1)Glibness/superficialcharm.

(2)Grandiosesenseofself-worth.

(3)Needforstimulation/pronenesstoboredom.

(4)Pathologicallying.

(5)Cunning/manipulative.

(6)Lackofremorseorguilt.

(7)Shallowaffect.

(8)Callous/lackofempathy.

(9)Parasiticlifestyle.

(10)Poorbehaviouralcontrols.

(11)Promiscuoussexualbehaviour.

(12)Earlybehaviouralproblems.

(13)Lackofrealisticlong-termgoals. 22 Engelhaupt,2023 23 Forareviewofthesemisconceptions,see Sellbometal.,2022 24 Braziletal.,2018; Jurjakoetal.,2020; Maraun,2022. 25 Cleckley,1988.

(14)Impulsivity.

(15)Irresponsibility.

(16)Failuretoacceptresponsibilityforownactions.

(17)Manyshort-termmaritalrelationships.

(18)Juveniledelinquency.

(19)Revocationofconditionalrelease.

(20)Criminalversatility.26

Qualifiedandtrainedmentalhealthcliniciansscorethesetwentyitemsbyusing severalinterviewsandanalysingthe filesofthesubject.BasedondetailedguidelinesinthetechnicalPCL-Rmanual,eachitemcanbescoredas0,iftheitemdoes notapplytotheindividual;1,ifthereissomebutinconclusiveevidencethatthe itemappliestothesubject;and finally2,iftheitemappliestotheindividual.27

Scoresrangefrom0to40andacut-offvalueof30isoftenusedinNorthAmerica todiagnosepsychopathy,whileinEuropeacut-offvalueof25ismorecommon.

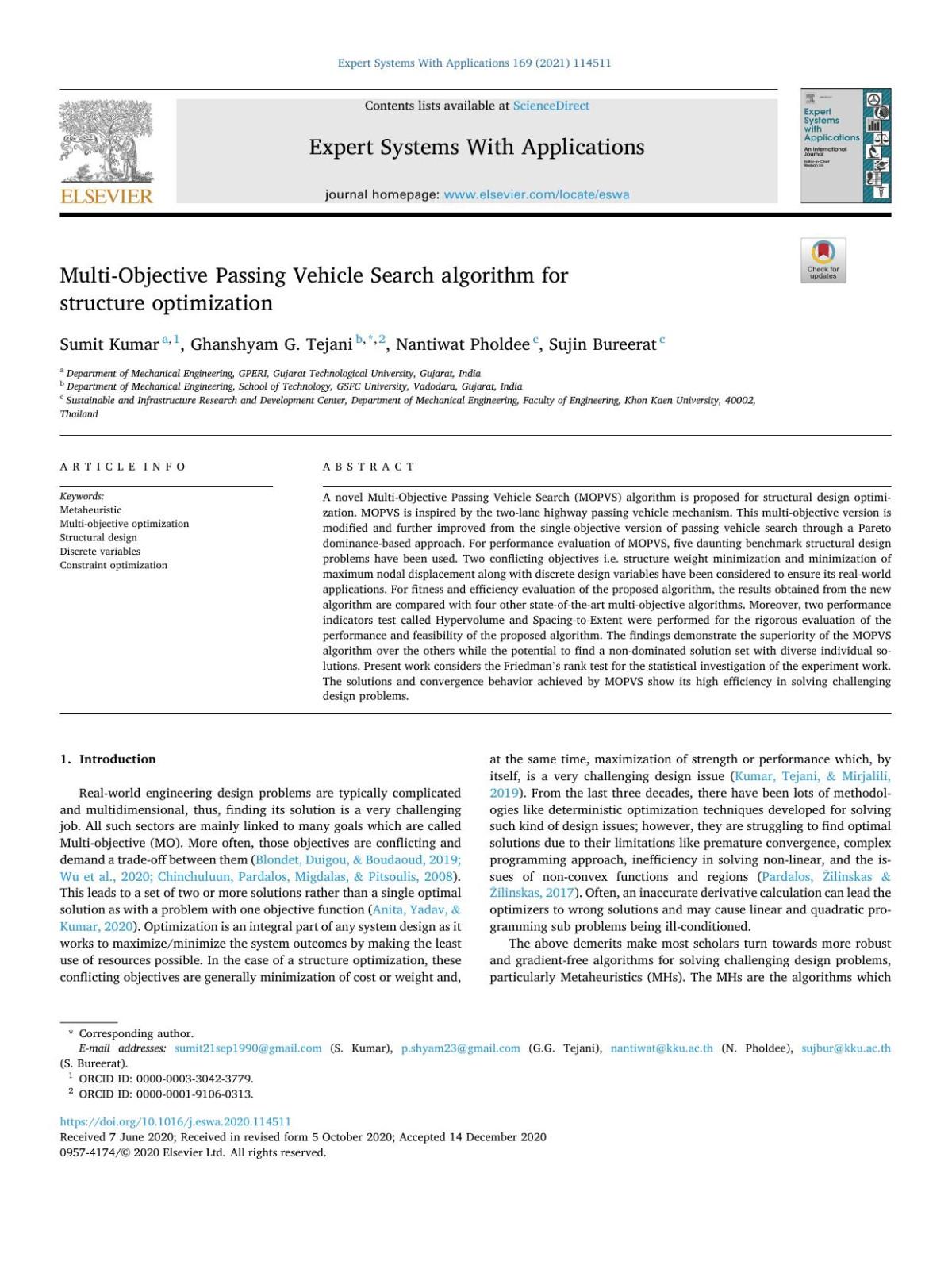

RobertHareandcollaboratorshavepromotedthePCL-Rasafour-facet structure,wherethesefacetscanbegroupedintotwomainfactors,the ‘affective/interpersonalfactor ’ (Factorone)andthe ‘socialdeviant’ factor(Factor2).28

Forthepurposeofourintroductionwepresentthisstructurein Table1,although otherstructureshavebeenadvanced.29

Table1Thefour-factormodelofPCL-R(adaptedfrom Hare2003,p.83)

Factor1

Facet1:Interpersonal

1.Glibness/Superficialcharm

2.Grandiosesenseofself-worth

4.Pathologicallying

5.Cunning/Manipulative

Facet2:Affective

6.Lackofremorseorguilt

7.Shallowaffect

8.Callous/Lackofempathy

16.Irresponsibility(failuretoaccept responsibility)

Factor2

Facet3:Lifestyle

3.Needforstimulation

9.Parasiticlifestyle

13.Lackofrealisticlong-term goals

14.Impulsivity

15.Irresponsibility

Facet4:Antisocial

10.Poorbehaviouralcontrols

12.Earlybehavioural problems

18.Juveniledelinquency

19.Revocationofconditional release

20.Criminalversatility

26 Hare,2003,p.1. 27 Hare,2003 28 Hare,2003,p.83.

29 See,forinstance, Cooke&Michie,2001.

Theitemsthatdonotloadintoanyfactororfacetare11(Promiscuoussexual behaviour)and17(Manyshort-termmaritalrelationships).

TheconstructofpsychopathyasmeasuredwithPCL-R,andwithother measures,hasbeenthefocusofincreasingscientificresearchinrecentyears. Studiesanddebateshavecentredontheappropriatewaystomeasurethe constructofpsychopathyandinvestigationofthepsychometricpropertiesand relationsbetweentheavailablemeasures.Investigationsofthefunctional characteristicsofthiscondition,itsneuralcorrelates,anditsgeneticunderpinninghavealsobeenundertaken.30 Moreover,expertsandpractitionershave studiedtheclinicalapplicationoftheconstructofpsychopathy.31 And, finally, theethicalandlegalconcernsitraiseshavebeenconsidered.32 Thepolicy,legal, andethicalissuesareunderpinnedbypsychologicalandneurologicalresearch programmes,anditisthereforeaninstanceofneuroethcisbeingcharacterised wellbyitsdomain.

2.5TheRolesofConceptualAnalysis

Ifwetakeneuroethicstobeaninterdisciplinary fieldwhosedomainisresponsivetodevelopmentsinneuroscienceandotherrelevantareassuchaspublic policy,thenthewaysinwhichneuroethicsanalysesconceptsshouldreflectthis. Therearedifferentwaysofdescribingconceptualanalysis,butwethinkit involvesengagingnotonlywiththerelevantconcepts,betheyneurological, legal,orphilosophical,butengagementtoadepththatcandojusticetotheuse ofthatconcept.Thatisnottosaythatconceptualanalysisinneuroethicsshould notaimatbeingcritical,northatweshouldtakethewayinwhichaconcept happenstobeusedtobehowitmustbeused.Wethinkthatconceptsshouldbe rootedinsuchawaythattheyareempiricallygroundedinadditiontobeingwell explicatedatatheoreticallevel.Moreover,wethinkthatthereisaKantian argumentthatexplainswhythisfollowsfromtheimportanceweattachtothe relevancecondition.

Inthe CritiqueofPureReason ImmanuelKantclaims:

Itcomesalongwithournaturethat intuition canneverbeotherthan sensible, i.e.,thatitcontainsonlythewayinwhichweareaffectedbyobjects.The facultyfor thinking ofobjectsofsensibleintuition,onthecontrary,isthe understanding.Neitherofthesepropertiesistobepreferredtotheother. Withoutsensibilitynoobjectwouldbegiventous,andwithoutunderstandingnonewouldbethought.Thoughtswithoutcontentareempty,intuitions withoutconceptsareblind.33

30 Patrick,2018 31 Gacono,2016 32 Kiehl&Sinnott-Armstrong,2013; Malatestietal.,2022 33 Kant,1998a,pp.193–4:A51/B76.

Therearetwoinsightsherethatarerelevantforconceptualanalysiswithin neuroethics.The firstisthatwithoutreferencetotheempirical(theworld), rationalitythatconsistsonlyinthemanipulationofconceptswillfailtobeabout experience.So,whenKantsaysthatthoughtswithoutcontentare ‘void’ he meansthatwithoutperceptualinteractionorsomekindofengagementwiththe waythingsare,ourthoughtswouldbeempty.Inthecaseofneuroethics,this argumentsuggeststhataccountsofphenomenathatfallwithinthedomainof neuroethicsmustbegroundedinevidenceandtheworkthatdisciplineswhich studythedomainempiricallyconduct.Soneuroethicsshouldbeempirically groundedinneuroscience,theactualpracticesoflaworclinicalreality.

Thesecondinsightisthatwithoutconceptswecannothavemeaningful perceptionsorthoughts.So,itisimpossibleforustounderstandhowto perceivebeautyinaportraitwithoutaconceptofbeautythatenablesustosee whatisinthepainting.Whenthisisextendedtothedomainofneuroethics adegreeofsophisticationisimpliedwhenitcomestograspingconceptsthat derivefromneuroscience,clinicalpractice,law,orphilosophy.Forexample, aneuroscientistmightargue,basedonidentifyingauniquepatternofbrain activationinindividualswithanaddiction,thattheylackfreewill.Tomakethat normativeinference,thereshouldbeadegreeofsophisticationandconnection withthephilosophicaldiscussionoffreewillandhowitrelatestoconceptssuch asdeterminismandmoralresponsibility.Achievingthisdoesnotrequire neuroscientistsandneurosurgeonstomasterphilosophy;yetthisisexactly whyweneedtheinterdisciplinarityofneuroethicsandcollaborationbetween philosophers,neuroscientists,andneurosurgeons.Anexemplaristheworkof DirkDeRidderetal.,inwhichtheydiscussmajorphilosophicalpositionson freewillandthenarguethatitisanillusionbasedonevidenceaboutthe predictivenatureofbrainfunctions.34 Whatmakesthispossibleisactive collaborationbetweenandanappropriatedivisionofintellectuallabour betweenneuroscientistsandphilosophers.

Anotherwayofframingtherelevanceconditionsofneuroethicsisintermsof ‘ecologicalvalidity’.Thisisaconceptthatisusedinseveraldifferentcontexts butalsoinpsychologywhenconsideringwhetherbehaviourobservedunder laboratoryconditionsoccursinanaturalenvironment.35 Forexample,aprimate mightdemonstratealanguagelearningabilityundercontrolledlaboratory conditions:thatobservationwouldbeecologicallyvalidifitalsooccurredin theprimate’snaturalenvironment.36 Wethinkasimilarthingcanoccurwith concepts.So,forexample,aphilosophermightreasonthatithastobethecase foranagenttobeconsideredmorallyresponsiblethattheyhaveacquired

34 DeRidderetal.,2013. 35 Schmuckler,2001. 36 Dennett,1989.

a ‘reasonsresponsivemechanism’ thattheyidentifyastheirown.37 Thephilosophicalvalidityofthatconceptfollowsfromananalysisofwhatmustbethe casefortheretobemoralresponsibility.However,thereremainsanecological questionaboutwhether,infact,youngpeopledogothroughaprocessof acquiringtheabilitytoseethemselvesashavingtheabilitytorespondto reasonsandasappropriatetargetsforpraiseandblame.Whetherornot areasonsresponsivemechanismdevelopswilldeterminewhethertheconcept isecologicallyvalid;inotherwords,whetheraphilosophicalconceptappliesto thewaysthingsarewhenweconsideritempirically.Neuroethicsshouldaimfor a ‘reasonable’ degreeofecologicalvalidity,inthesensethatthoseworking withinthesamedomainarelikelytoagreethatthewayaconceptisusedmakes senseandisapplicabletohowtheymightuseit.Ifourconceptsfailtobe ecologicallyvalidthentheyrisknotbeingrelevanttothedomainofneuroethics.

Aswellastheimportanceofaimingatecologicalvalidityandourconcepts meetingrelevanceconditions,conceptualanalysiscanhavethreedistinctoutcomeswithinneuroethics.Itcanbe:

• descriptive,

• revisionary,or

• eliminative.

Forexample,ifwewanttounderstandwhatnewneurological findingsmeanfor thewayinwhichanimpairedabilitytocontrolviolentimpulsesisconsidered bythelaw,wecouldanalysethewayinwhichthelawworksinoneofthree ways.Itmightbethattheconceptualanalysisofthelawmakessensegiventhe neurological findingsandwhatwethendoisdescribehowthelawoperatesand isunderpinnedbythisneuroscience.

Anotherpossibilityisthatneurosciencemightdemonstratethatitismore feasibletogenerateevidenceabouthowsomeone’simpulsecontrolhasbeen impairedthanwaspreviouslythoughttobethecasebythelaw.Insuchacase, oncewehaveunderstoodhowthelawviewstheseimpairmentsandwhatthis neurosciencemeans,wemightgenerateaconceptualanalysisthatisrevisionary.Itdescribes,partiallyaffirms,buttosomeextentreviseshowthelawviews suchimpairments.Ofcourse,changingwhatthelawdoesisanothermatter,but arelevantconceptualanalysisthatiswellgroundedinthatdomainmight provideastrongargumentforrevisionstothelaw.

Thethirdpossibilityisthatconceptualanalysisprovidesanargumentfor eliminatingthatlegalpractice.Ifneurosciencegeneratedresultswhichshowed thatthewayinwhichthelawviewedimpairedcontrolwascompletelyatodds

37 Fischer&Ravizza,2000.